November 2019

- Home

- Branches

- United Kingdom

- Birmingham

- BRUM RATION

- November 2019

REMEMBRANCE

For the last four years I have featured in the November Issue of Brumration those men from Sutton Coldfield whose names are on the Sutton Coldfield War Memorial. Their sacrifice will never be forgotten as could be seen again this year in the crowds that gathered for the commemorations at the memorial and at Holy Trinity Church on Remembrance Sunday. I know that many of you will have been at services elsewhere but Jonathan laid a wreath on behalf of the Birmingham Branch on the Sutton Coldfield Memorial. I was impressed by a young man interviewed on Midlands Today who said that at a time when the country was so divided it was good that we could all come together with one purpose to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

BRITISH PRISONERS OF THE TURKS

At last month’s branch meeting we heard a talk by Alan Wakefield on the ‘Crisis at Kut’ and it is a subject that has also featured in Brumration. The events at Kut were clearly a serious setback for the British which resulted in the capture of over 13,000men. The Report on the Treatment of British Prisoners of War in Turkey published in 1918 provides a breakdown of this figure. It divides the men into British and Indian which I am not sure is helpful as they were after all part of the same fighting force. However there were 284 British Officers and 2,680 other ranks captured and 222 Indian Officers and 10,486 other ranks captured at Kut el Amara. The total number of British and Indian prisoners held by the Turks was estimated in October 1918 as 16,583 so the vast majority of prisoners were taken at Kut el Amara.

Thirty one British Officers and 374 other ranks were captured at Gallipoli and were taken from there to Constantinople. There are some surviving accounts , including that of Private William Frederick Nelson, 1st/8th Territorial Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers, who recorded his memories some years later at the Imperial War Museum. He was captured on 7th August 1915 and his first meal the day after capture was a glass of water and half a chapatti. The following day he had a boiled maize meal served in a large dish which a group of men would eat out of with their hands. Sometimes it would have olives, once they found a sheep’s eye. This would all seem very strange to young British soldiers who had never left their home towns before but as required by International Law the food was similar to that given to the Turkish soldiers.

Private Nelson had his boots stolen by Turkish soldiers soon after capture, and this was a common occurrence. On arrival in Constantinople he was marched with other prisoners through the streets to Stamboul Goal. There were many curious onlookers but no hostility. He was then interviewed and these records are still available. They indicate he had been a clerk in a chocolate factory in Manchester, Fry’s, and that he had lied about his age to volunteer for the Army. He was only just 18 at the time of his capture.

There are also details of the men who were captured at the same time as him. One was from the 8th Lancashire Fusiliers, one from the 7th Lancashire Fusiliers, two from the Worcestershire Regiment and one from the Hampshire Regiment. All these reports contain a line stating that they are being well treated. It is interesting that these files also contained letters, which had been written by the men and intercepted by the Turks.

By March 1916 Nelson was in a Work Camp at Belemedik where the Turks made it clear they would provide no more food and that they had to earn a living or starve. The prisoners worked a twelve hour shift and were all weakened by malaria and dysentery. Nelson was selected for a prisoner exchange in November 1917, but was in hospital at the time with malaria. He arrived back in the UK in December 1918 and after treatment at The 2nd Western General Hospital by February 1918

they claimed he had no disability.

Those prisoners from Kut el Amara were already in poor condition at the time of their capture. Brigadier Kenneth B S Crawford, Royal Engineers recorded in his diary that by the end of the siege they were burying up to 80 men a day.

By 10th April 1916 all the mules and draught animals had been killed for food so at that point all the Officers’ horses were shot. Lt Edward Mousley, Royal Field Artillery, had studied Law at Cambridge but was serving with the Army in India when he was sent to Kut el Amara as a replacement. His horse Don Juan was one of those shot and as apparently was the custom he had its heart and kidneys for dinner that night.

On the surrender of Kut el Amara there were 1,450 sick and wounded in the town. Of these 1,100 of the worst cases were sent down the Tigris for repatriation and so escaped becoming honoured guests of the Turks. When the Turkish Army entered the town there was systematic looting and some British officers had items stolen at gunpoint. R A M C and Indian Medics had all their equipment stolen.

The following day the men were marched eight miles up river to Shamran. It was a bare piece of desert but they were to remain there until they could be sent to Baghdad. They had no rations for two days, but the local Arabs sold dates and black bread in exchange for boots, clothing and water bottles. Within a week nearly 300 men had died from dysentery and gastroenteritis.

The Turks appeared to have neither the power nor the will to protect the lives of the prisoners and refused all efforts by the British officers to support the men. On 6th May the officers were separated from the men, some of whom were already too weak to make the journey except by boat. The officers were allowed a reduced baggage allowance of 30 lbs.

It had been agreed that the men would only march eight miles a day. This only happened on the first day and for the rest of the journey they covered 12-15 miles a day. They had no shelter at night, food was short, and during the day the heat was intense and the dust constant. Many had no boots or water bottles, but their Arab escort were dressed in stolen British uniforms. A solitary Turkish doctor did his best to help.

There were deaths every day, the bodies left by the roadside. On the fourth day 350 men, too sick to march any further, were left behind in some sort of animal shelter to await river transport. After nine days marching the survivors arrived in Baghdad, but this was only the first leg of their journey.

The men were in hospitals across the city, RAMC Officers did improve the sanitary conditions a little, supported by French Sisters of Charity and Nuns, but the death rate remained high. Of 25 prisoners captured before Kut el Amara, 19 died from dysentery and septic poisoning.

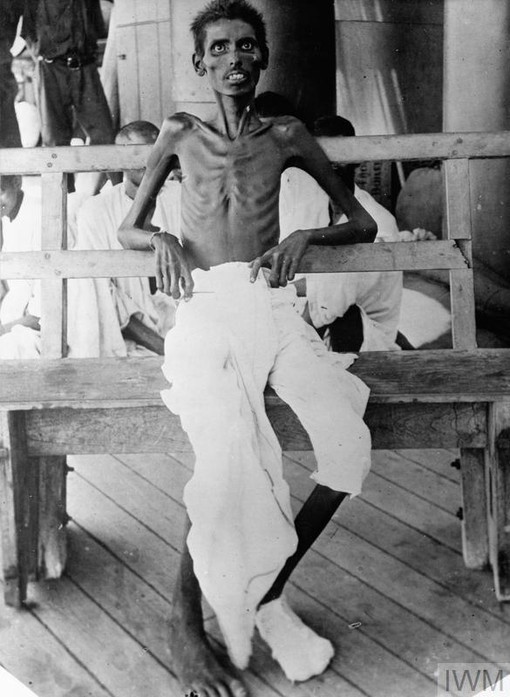

The Turks were anxious to move the prisoners on as soon as possible, fearing a Russian attack. Even the officers were marching on the next part of the journey although those who were sick were allowed to ride on the baggage train. Lt. Mousley lost his tropical helmet in a severe sandstorm, but heard at Nusaybin that an officer had died in the town and went off in search of his helmet. He found a courtyard, the inner sides of the walls lined with emaciated men lying under improvised sunshades. Most were completely naked apart from a loincloth, their faces hollow and they had little food. They had to crawl to a nearby watercourse to get a drink. Many were dead or dying, their faces covered by flies. These men were the survivors of Kut el Amara.

Information about the conditions of these prisoners only slowly filtered through to the authorities in London. The Turks were the only power to refuse permission for any neutral power to visit the camps, despite persistent efforts by the American Embassy in Constantinople. From 1917 the Dutch Legation applied similar pressure and under the terms of The Berne Agreement of December 1917 there was an undertaking that a Dutch representative should have access to the camps. No such visits appear to have been made.

The 1918 Report relies heavily on evidence from the few individuals who were able to visit the prisoners. In the summer of 1915 a messenger from the American Embassy did manage to visit one camp at Afion Kara Hissar on one occasion. Two Roman Catholic Priests sent by the Papal Nuncio and two delegates from the ICRC were allowed some access in 1916. All other letters and visits to the Dutch Legation were forbidden by the Turkish Authorities.

There was more information available as some of those

prisoners captured at Kut were repatriated, but however dreadful their accounts they had only a small part of the story.

Prisoners of the Germans on the Western Front relied heavily on Red Cross Parcels and parcels from home to survive. The Turkish postal system was not up to the challenge. Even if the parcels got as far as Constantinople there was no guarantee they would arrive at destinations further east. One letter sent to Private Nelson in October 1915 was returned to his home address in May 1920. Unlike on the Western Front there was no guarantee that officers letters would get through either. One letter from Major General Sir Charles Mellis sent to Lloyd George in 1918 did get through via a Russian Officer who had been part of a prisoner exchange.

The 1918 Report on the Treatment of Prisoners in Turkey suggests the treatment of prisoners reflected what it describes as an’ Asiatic indifference’ in its serious disregard for the rights of a few thousand disarmed men. ‘Some may be due to muddle but the Turks spared no effort to conceal the results of their neglect’. Modern texts take this further and reflect that the treatment of POW’s by the Turks in World War 1 was a pre-cursor for what was to happen to prisoners of the Japanese in World War 2.

Sources Report on the Treatment of British Prisoners of War in Turkey. Miscellaneous No.24, 1918

Tracing Your Prisoner of War Ancestors: The First World War by Sarah Paterson

The Beauty and the Sorrow by Peter Englund