23 December 1915 : Roland A Leighton

- Home

- On This Day

- 23 December 1915 : Roland A Leighton

Roland Aubrey Leighton was born on 27 March 1895 in St.John's Wood, London.

Roland Leighton was the oldest surviving child of literary parents, Robert Leighton ('man of letters) and Marie (née Connor), a novelist. As a result of the guilt following the death of her first child, Marie spoilt Roland and neglected his younger siblings-sister Clare and brother Evelyn.

Roland went to prep: school in St.John's Wood (London House) and followed by a scholarship to Uppingham in 1909. Other entrants in September were Edward Brittain and Brian Horrocks (who survived the war, rose to General, and was actively involved in the Second World War).

Roland had a distinguished career at Uppingham, winning numerous prizes, and becoming House Captain. He was seen by some to be aloof, and was known by his nicknames of 'Monsignor' or 'The Lord.' He formed close friendships with Edward Brittain and Victor Richardson; Roland's mother called the triumvirate 'The Three Musketeers'.

In July 1913, Roland met Edward Brittains' sister Vera, when she attended Speech day. He was invited to the Brittains' house, Melrose, Buxton, in April 1914, where he and Vera became friends. They were soon corresponding regularly, and Vera agreed to attend Speech Day despite being in the throes of preparing for her Oxford entrance examinations.

In 1914 Roland gained a scholarship and exhibition to classical postmastership at Merton College, Oxford. Edward was to go up to New College Oxford and Victor to Cambridge.

Roland collected so many prizes on speech Day that an old boy later recalled him taking them back to his dormitory in a wheelbarrow. The headmaster of Uppingham, Reverend Mackenzie gave a speech which ended with a quote from a Japanese General, Count Nogi-"Be a man-useful to your country; whoever cannot be that is better dead."(1)

After the prize giving Roland and Vera spent time talking and walking in the rose garden at the Headmasters garden party. He composed the poem 'In the Rose Garden'.

Dew on the pink-flushed petals,

Roseate wings unfurled,

What can, I thought be fairer

In all the world?

Steps that were fain but faltered

(What could she else have done?)

Passed from the arbour's shadow

Into the sun.

Noon and scented glory,

Golden and pink and red;

"What after all are roses

To Me?" I said.

Roland Leighton, July 11th, 1914 (2)

Shortly after Speech Day, the Three Musketeers were at OTC Camp, but were hurriedly sent home owing to the outbreak of the war with Germany. Seventeen of the 66 boys who went to Uppingham School in Roland's intake were to lose their lives in the Great War; in all 450 alumni died serving their country 1914-1918.

Roland was also keen to enlist, but was having problems owing to poor eyesight. Edward Brittain succeeded in obtaining a commission in the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment. Eventually, Roland was commissioned into the Norfolk Regiment, having persuaded a family doctor to issue a medical certificate, which made no mention of his shortsightedness.

In October 1914 Vera went up to Somerville College, Oxford. While she came to terms with her new surroundings and lifestyle, Roland continued to write to her regularly, describing his training. One of the NCOs who served with Roland was the writer R.H Mottram, who was to write the Spanish Farm trilogy.

Roland and Vera agreed to meet up during the Christmas holidays, and spent two days together (albeit chaperoned by her Aunt) in London. On New Years' Eve, Vera realised that she was in love with Roland.

In those heavily chaperoned days, it was difficult for young people to be alone together, but a clandestine meeting was arranged to take place on Vera's return journey to Somerville. They met at Leicester station and eventually Roland accompanied Vera to Oxford.

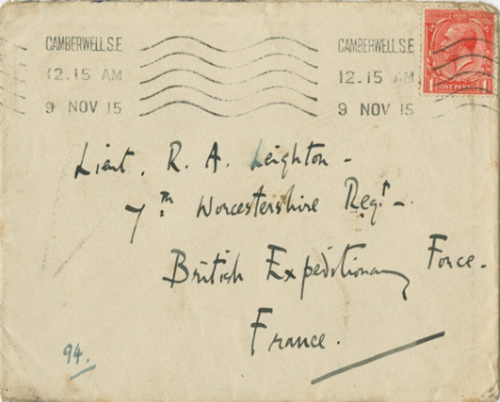

It was to prove a difficult term for Vera, trying to concentrate on her studies while thinking about Roland. She became ill with flu, and returned home early, only to have a letter forwarded from Oxford informing her that Roland had transferred to the 1/7 Worcestershire Regiment, and was expecting to go to France soon. It was arranged that Roland should come and stay the night. The next day, 19th March 1915 Roland left, and later sent Vera an amethyst brooch as a memento of the day.

Roland crossed to France on the night of 31st March, sailing from Folkestone to Boulogne, and then to rest camp. They then travelled by train and by foot to billets south of Bethune. Roland wrote his first letter to Vera on April 3rd, and told her that they could hear the guns in the distance.

Roland's letters to Vera very quickly showed that there was nothing glorious about sitting in a trench. Vera begged Roland not to spare her any details in his letters, although they would have been censored, just as Roland had to censor his mens' letters. His early letters question whether he will be afraid when he finally came under shellfire.

The Worcester's held a part of the front line in Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the soldiers) for most of April. Roland's letters are also full of the incongruities of war; in one letter he is amazed at some primroses growing near his dugout. In the same letter, he reports that the Worcesters had had their first man killed. He also told Vera about finding the body of a British Soldier who must have lain where he was for some time. It was to form the basis for another of his poems.

Villanelle

Violets from Plug Street Wood,

Sweet, I send you oversea.

(It is strange they should be blue,

Blue, when his soaked blood was red,

For they grew around his head;

It is strange they should be blue.)

Violets from Plug Street Wood-

Think what they have meant to me-

Life and Hope and Love and You

(And you did not see them grow

Where his mangled body lay

Hiding horror from the day;

Sweetest it was better so.)

Violets from oversea,

To your dear, far, forgetting land

These I send in memory,

Knowing You will understand. (3)

(Roland actually wrote the poem on April 25th, but was not to show Vera the poem until August).

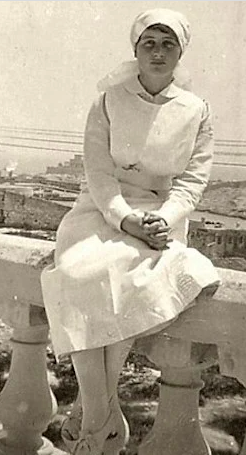

Vera decided to become a Voluntary Aid Detachment Nurse, initially during the summer vacation. She welcomed physical activity, and in nursing the wounded, she hoped to become closer to Roland and be prepared for when he came home with a wound.

Roland wrote that the first man in his company had been killed on 9 May; he wondered whether he should be telling Vera these things, and urged her not to remember, as he did. He regretted that he was unable to write longer letters to her, but finished by saying she would understand.

Roland's letter of 4th June tells Vera that he had just been to his first funeral, at 'our little cemetery on the road to the trenches.'(4) The dead 'man had been recommended for the DCM for laying a telephone wire under fire a week or two ago. It is such a pity that he could not live to wear it.'(5)

The dead man was Lance Corporal John Beagin.

On June 27th, after completing Pass moderations exams, Vera began her new life as a VAD nurse at the Devonshire Hospital, Buxton. Although totally unused to the hard physical work, Vera was an enthusiastic addition to the nursing team. Most of the patients were not seriously ill, and her youthful looks and enthusiasm made her popular with the patients.

On August 19th,Vera received a postcard from Mrs Leighton informing her that Roland was due home on leave that day. Vera was able to obtain weekend leave from the hospital, and arranged to meet him at St Pancras Station the next day. Vera also agreed to visit the 1st London General hospital for an interview.

The sight of Roland made Vera alarmed when she first saw him. He looked older, thinner and shabby. Despite their intimate correspondence over the last months, they were shy and ill at ease with each other. They had to readjust to each other's physical presence. Following Vera's interview, and a shopping trip, they set off on the train to Buxton. During the journey, Roland proposed to Vera.

Roland's leave was crammed with train journeys; after visiting the Brittain's at Buxton, they went to stay with the Leighton's at Lowestoft. They also managed to have lunch with Victor and Edward. One wonders whether Roland imagined such a leave, he had so little time to readjust to life in England yet he spent much of his precious time travelling. They managed only one moment of real intimacy during the stay at Lowestoft, when they were sitting on a cliff.

Their parting on Monday 23rd August was painful. Forced to say goodbye on the platform at St Pancras before she boarded the train, Vera was astonished by the anguish shown by Roland. In one of the most moving passages in Testament of Youth describes how she watched Roland walk away from the train as it drew away, never turning back.

Roland arrived back in France on August 26th, and wrote to Vera asking whether the last days had been real, and concluded that the felt "as if someone had uprooted my heart to see how it was growing."(7)

His letters in the remainder of August and September are almost daily; he seemed to find it easier to express his feelings in words than in person. Vera's letters are full of longing for him, as the memory of his physical presence was fading fast. She was later to write that when they were apart, she was unable to recall his features.

The Worcester's were by now serving on the Somme, near Hebuterne, and Roland wrote to Vera that they would be involved in the fighting at Loos, which began on 25th September. This proved to be a false alarm, but the news gave Vera some very anxious days of waiting, and she sent him a farewell letter, just in case. One consequence of the battle of Loos was that Vera was called to the 1st London General Hospital, as there were many wounded coming in.

Vera gradually got used to her new surroundings. The work was a lot different from the Buxton Hospital, and the wounds were a lot worse. Vera was to describe them as having a "butchers shop appearance." Vera now began to hope that Roland would not get wounded, as she had hoped for.

Roland letters were becoming less frequent and shorter. They were cynical and he expressed his absorption in his world. He may have decided that the only way to cope was to shut out all he cared for. This was a common reaction of men at the front, but a source of bewilderment for those at home. Vera was dependent on the 'Rupert Brooke' image of the war, despite her nursing of the wounded. Roland, who had seen war at first hand, had a different perception.

After a long period of silence, Roland sent Vera a letter, which angered her. She was reluctant to send him a stinging reply, in case it was the last letter he ever read. However, she was frank in her reply, reminding him that "war kills other things apart from physical life."(8)

Roland was at the time acting as adjutant to the Somerset Light Infantry, and letters were slow in getting to him. His reply to Vera's frank letter written in November was contrite and unhappy. He also hinted that he might have some leave due.

His letters from now on are more warm, but rather dispassionate. They appear to be looking at their relationship in a detached way, expressing concern over Veras' physical hardships. A poem written about this time expresses his feelings, although Vera was to put a different slant on it.

Hedauville

The sunshine on the long white road

That ribboned down the hill,

The velvet clematis that clung

Around your window-sill

Are waiting for you still.

Again the shadowed pool shall break

In dimples at your feet,

And when the thrush sings in your wood,

Unknowing you may meet

Another stranger, sweet.

And if he is not quite so old

As the boy you used to know,

And less proud, too, and worthier,

You may not let him go-

(And daisies are truer than passion-flowers)

It will be better so. (9)

On 13th December, he wrote to Vera informing her that his leave was 24th-31st December. She managed to obtain Christmas leave and spent the next few days excitedly preparing for his homecoming. Mr and Mrs Brittain had left Buxton and were temporarily living at the Grand Hotel, Brighton, and the Leightons were renting a cottage at Keymer in Sussex.

Vera came off night duty on Christmas morning, and travelled to Brighton to await Roland's return. When she had heard nothing, she decided that his crossing had been delayed or that communication had been difficult.

On Boxing Day, she was called to the hotel telephone. "Believing that I was at last to hear the voice for which I had waited for twenty-four hours, I dashed joyously into the corridor. But the message was not from Roland, it was from Clare; it was not to say that he had arrived home that morning, but to tell me that he had died of wounds at a Casualty Clearing Station on December 23rd."(10)

At midnight 22-23 December Roland's platoon was to repair the wire in front of the trench; before letting his men begin the work Roland went forward himself to examine the spot. Just as he reached the wire the Germans opened fire and he was shot in the stomach, the bullet coming out the back. He was taken to hospital at Louvencourt where he died the following evening. (11)

His Colonel wrote of him :

“He had a wonderful brain, very quick to grasp anything, and it was that which first appealed to me in him. He was a splendid soldier and very popular with all I liked him so well that I made him my Acting Adjutant’.

He is buried in the CWGC cemetery at Louvencourt, near Doullens.

After completing her studies at Oxford, Vera went onto to marry the political scientist, George Catiln in 1925, and they had two children, John and Shirley (who is now Baroness Williams of Crosby.)

Roland's age is incorrectly given on his headstone and in the details being 19, he was in fact nearly 21. His mother suffered a breakdown following his death, and Vera was devastated, although she gradually recovered, and continued nursing throughout the war, serving in Malta and France. She was to visit his grave at least twice, in 1921, and again in 1933.

Vera had a long career as a novelist and journalist. She was to become a prominent pacifist and member of the Peace Pledge Union. Amongst Veras' 29 books, she left a poignant and much loved memoir to Roland, Edward (killed June 1918) Victor (died of wounds June 1917) and Edward's friend Geoffrey (killed April 1917) in the book Testament of Youth.

Vera died on 29th March 1970, her mind in eclipse. Two years earlier when being interviewed by the BBC, she was unable to recall who Roland was.

(1) Brittain, Vera, Testament of Youth. Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1934. (Kindle Edition p88).

(2) Ibid. (Kindle edition p50).

(3) Ibid. (Kindle edition p135).

(4) Bishop, Alan and Bostridge, Mark. Letters From A Lost Generation

(5) Ibid.

(6) CWGC website

(7) Testament of Youth (Kindle edition p193)

(8) Ibid. (Kindle edition p218)

(9) Ibid. (Kindle edition p253)

(10 Ibid. (Kindle edition p236)

(11) The Roll of Honour, UK, De Ruvigny's Roll of Honour, 1914-1919

Letter from Vera Brittain > http://www.acenturyback.com/2015/11/08/vera-brittain-writes-roland-leighton-the-kind-of-letter-he-deserves-raymond-asquith-on-foie-gras-and-greenfinches-dorothie-feildings-old-gang-is-breaking-up/