Ep. 134 – Bairnsfather’s Better ‘ole' cartoon – Dr Helen Brooks & Dr Pip Gregory

- Home

- The Latest WWI Podcast

- Ep. 134 – Bairnsfather’s Better ‘ole' cartoon – Dr Helen Brooks & Dr Pip Gregory

On this week’s Dispatches podcast, Dr Helen Brooks, Reader in Theatre and Cultural History, School of Arts, and Dr Philippa Gregory, History HPL Tutor, both from the University of Kent, talk about Bruce Bairnsfather’s famous ‘Other ‘Ole’ cartoon and its impact and resonance during the Great War and after.

Transcript

Tom Thorpe (TT): Welcome to ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’, the podcast from the Western Front Association with me, Dr. Tom Thorpe. The WFA is the UK's largest Great War history society. We are dedicated to furthering understanding of the First World War and have over 60 branches worldwide. For more information visit our website at www.westernfrontassociation.com.

It is the 28th of October 2019. And this is Episode 134.

On this week's ‘dispatches podcast’ Dr. Helen Brooks, Reader in Theatre and Cultural History and Dr. Philippa Gregory - History HPL Tutor, both from the University of Kent, talk about Bruce Bairnsfather's famous cartoon ‘The Other ‘ole’ - and its impact and resonance during the Great War and after. I spoke to Helen and Pippa from the University of Kent in Canterbury.

TT : Helen and Pip - Welcome to the 'Dispatches Podcast'. Can you start by telling us about yourselves and how you became interested in the Great War. Pip? It might be good to start with you.

Philippa Gregory (Pip): I started predominantly with the cartoon side of things, which is where ‘Better ‘Ole’' technically starts - and I think we met in the Special Collections at Kent University - when you started thinking about doing some theatre on the Great War - and I said, "I've got some cartoons about that".

Helen Brooks (Helen): Yeah. I was actually, weirdly, it came out of my teaching. My background originally was working on 18th Century theatre. I was teaching some students who were doing some stuff on Victorian/Edwardian theatre - and who were saying - they really wanted to do something on the First World War - and I was saying to them that nobody does anything on theatre in the First World War - it's this blank spot. And they did this incredible piece of work using two of the Special Collections - and at that point, I thought, okay - there's something really interesting here: 'why is no one looking at this? Where are these gaps?', and as Pip says, that's when we kind of bumped into each other. And so actually, we're both doing the First World War from different angles to how it's normally done as well. And then it kind of just spread from there - and then it was the centenary - and it had to stop.

TT: Today, we are going to be talking about Bruce Bairnsfather the cartoonist and his famous image ‘The Better ‘Ole’. Can we start by talking about who Bruce Bairnsfather was.

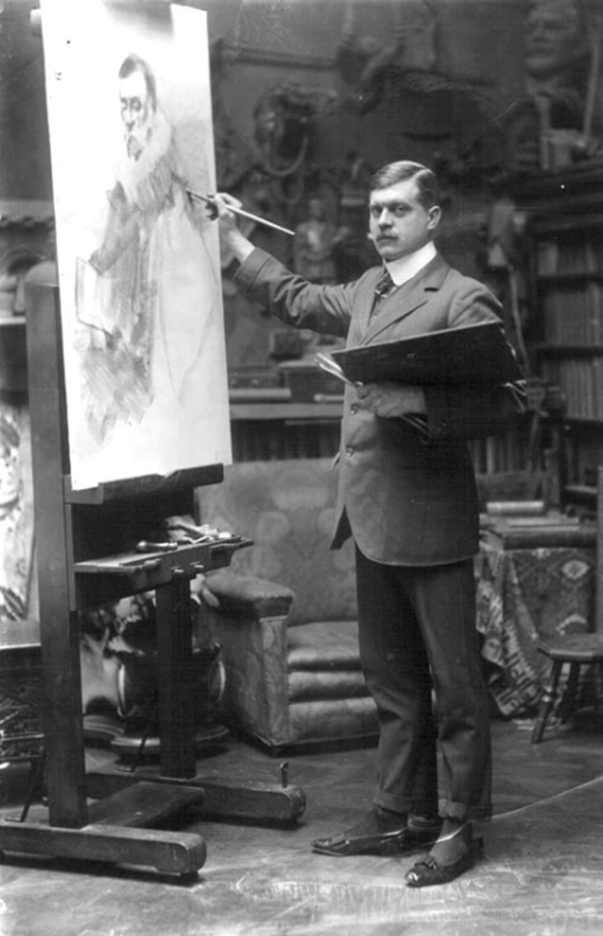

Pip: Well, Bairnsfather is - quite an unusual character in many ways. He was born in India in 1873 - and his father was in the military, so growing up his aspirations were very much that he wanted to join the military. He went to school in England and was notorious in school for doodling on his exercise books - so much so that there are anecdotes of the teachers asking for his books back - so they could keep them for his cartoons. So that is very much where his cartooning started, although he never saw himself as a cartoonist technically. He always believed he was better than that - and he was an artist. And it's for that reason that he went to art school.

He trained under John Hassall, who was famous as an artist and cartoonist at the time as well - and in so doing, he managed to become more proficient in his art. But he also took various exams to try and get into the military: he failed a couple of times. And I think it was about 1908 that he finally passed - and went into the Army.

He went in and acted as a soldier for a while until he was asked to leave.

I believe there may have been some illness related to that, and that was why he came out and he then went back into the public service at home - didn't enjoy it - got himself a job - in various positions. I think there was some architecture, some in gas work - some - in all sorts of bits and pieces that he did. And he managed to lose his job in about May or June time 1914 - and then this 'handy thing' called the First World War began around August - and so he signed back up - and he was able to get back into his second love, which was as soldier - and he went back into the army.

So, I think that takes us right back up to where we want to be on that, but it was, yes - very much two aspirations: art and military - all the way through.

TT: So how did he become a cartoonist in the trenches?

Helen: Well, as I say, he had always been an artist in some way, shape or form, but when he was in the Army he discovered that the Bystander regularly sent out, or editions of the Bystander - were sent out to them - and the images that were turning up looked familiar to the kind of thing that he did. So on that basis he took his shot in the dark - and send off a cartoon to the Bystander, which he did in early 1915 and it was accepted, and published, and was very popular. So they asked him for a few more - and he produced various images for the Bystander until around 1915 when he was shell-shocked out of the army.

There is another story of him being in hospital in Boulogne on his way back to the UK - and somebody else seeing his name on foot of his bed and saying, “You that Bairnsfather who makes the cartoons? Look - this cartoon which I've got here”.

And showed him.

“Yes, actually that's the one, that’s one of the ones that I did."

And he hadn’t realised quite how popular he had become. And so in doing that he continued to produce cartoons for the Bystander. And then in 1915, in the end, it continued on - he had become more and more popular - and coming up to Christmas they liked to have a big edition, big cartoon, make a point. So they asked for another cartoon and that was when he put this particular image together. He called it, ‘One of Our Minor Wars’. So not actually called ‘The Better ‘ole’ - that was a title came later, but he put the caption at the bottom:

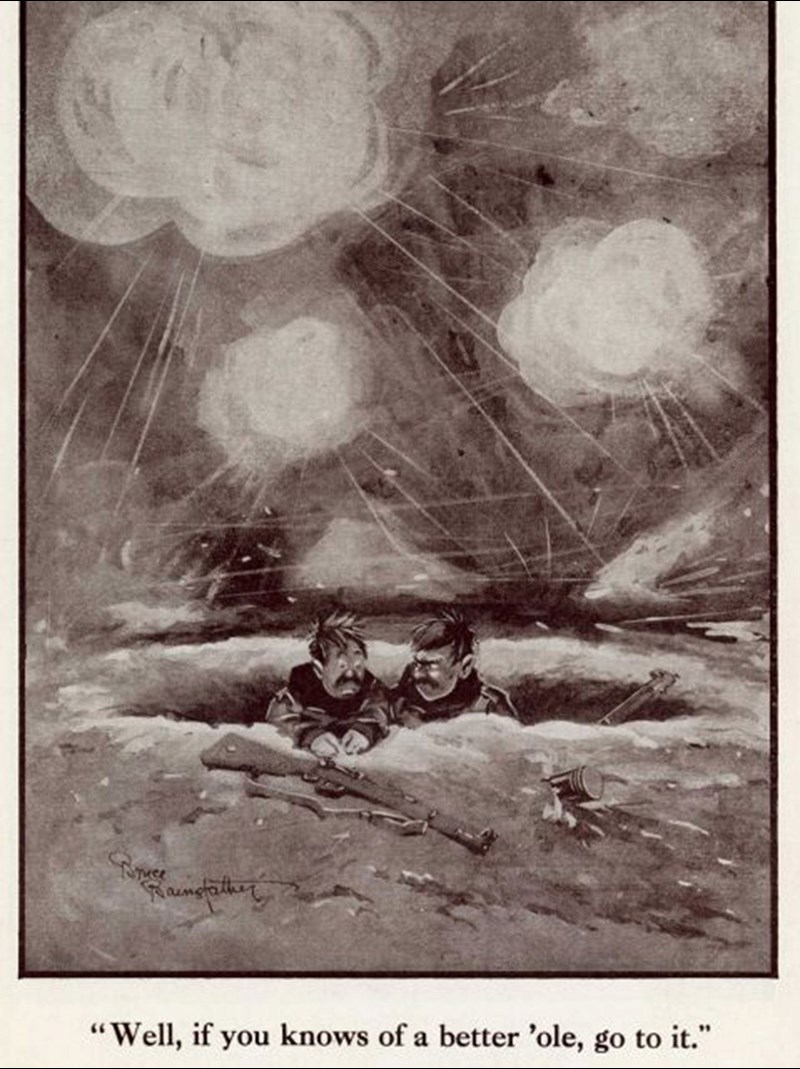

“Well, if you knows of a better ‘ole, go to it!”

TT: Which brings us neatly onto the challenge we have here in describing a visual medium through the means of audio. Can you tell us, or can you describe the image that we're all so familiar with?

Pip: So, it’s a very simple image in its own right … It is two soldiers, in a hole, in the middle of a battle, there are explosions and there are clouds with foaming about them. There is one gun that is set in front of the ‘ole - and there are two men in it, both looking a bit tired, a bit draggled and fed up. We assume one has asked the other, “Is there anywhere better we could be at this point?” and that is when the larger of the two characters, who we believe is most likely ‘Old Bill’ - who was Bairnsfarther’s by far the most common character who then says “If you know’s of a a better ‘ole, go to it”.

So it's that opportunity there has to be somewhere else that you could go, but actually there isn't at the moment - make the most of what you got.

TT: That brings us to our next question is: when was this image published? And how was it received?

Pip: About November 1915 that it was first published - and it was a very popular image - and Bairnsfather writes that he wasn't overly impressed with it he threw it out quickly just because they’d asked him for one. So he sent this image off quite quickly and the feedback from it was actually - that's a good idea - that makes sense.

So there's something that resonated with the general public at home and particularly the soldiers who were home on leave, who would say, “well, yeah, that's that's kind of what it's like”, trying to explain a situation they couldn't explain otherwise. So it became a very popular image

- and throughout the world. There are a lot of people going. “Oh, yeah. I remember that idea remember, that picture, and kept using it.

TT: Helen does it make it into the theatre?

Helen: It does. In fact that that point Pip’s just made about how it kind of becomes a means for people to talk to their loved ones at home about what it's like - that's the cruz of why it became so popular in theatre, - so you actually what happens is that Bairnsfather in July 1916 is developing a play with an established playwright called Basil MacDonald Hastings. And Bairnsfather doesn't think has written any plays before he's done a bit of amateur theatre, a bit of panto, but he - I think - what happened to him - is that he sees our the trench sketches - so other plays set in the front line in the trenches, which are being described by reviewers as being Bairnsfather characters.

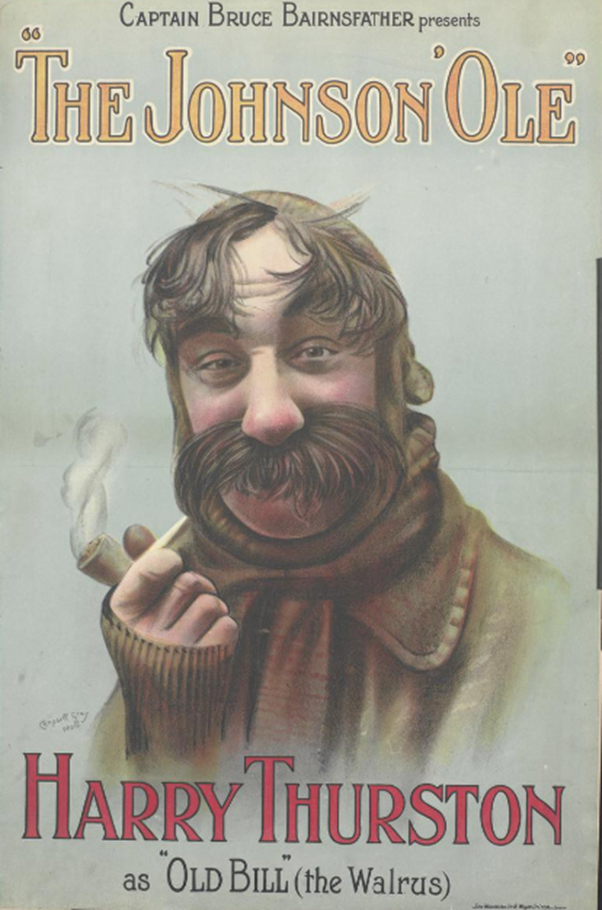

And so I suspect what he sees here as an opportunity here - to actually get on board - and to actually create a play - a piece of theatre himself. So, he started developing his first sketch - which is ‘Bairnsfatherland’ or ‘The Johnson ‘Ole’. And that’s around July 1916.

So in September 1916 that premiered at the Hippodrome in London - as part of a review called ‘Flying Colours’. So it's just a really short little sketch - but it becomes this massive hit and it gets performed over 200 times - and it then takes on a life of its own - and goes on and gets performed as an independent sketch in other reviews, at places like the Victoria Palace. So it becomes this whole entity in its own right - which is really unusual for such a short little ... it's kind of a 10 minute ... little sketch - which really is bringing to life the Christmas Truce. So it's set in Plugstreet - during Christmas 1914, which Bairnsfather had been at. So it is taking that kind of autobiographical experience of his and bringing it to life. So that becomes a big hit.

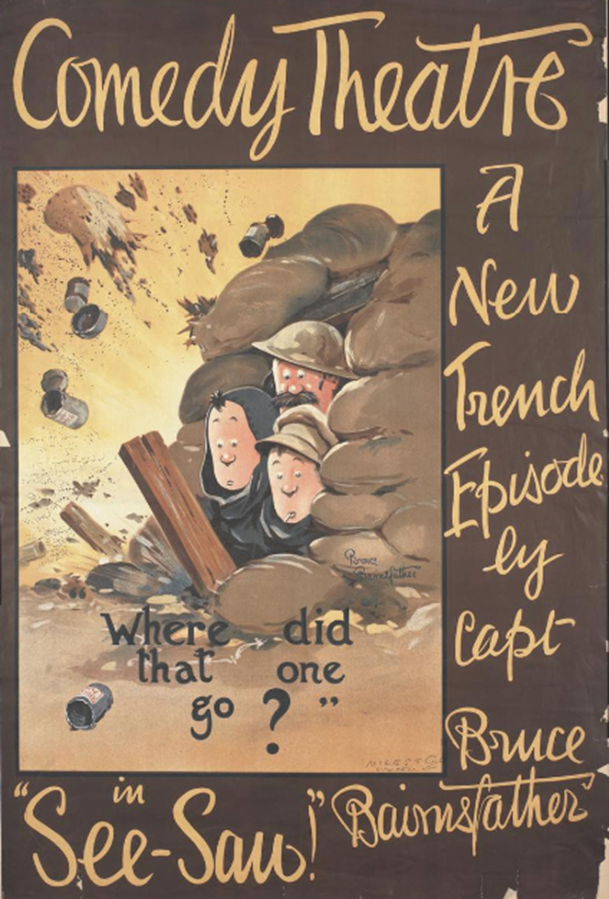

And then by mid January 1917 - so only a few months later, he's busy working on his next one, which is called ‘Where Did That One Go?’ and that one opens at the - is part of the ‘Seesaw’, which is another review at the Comedy Theatre in London. It doesn't have quite the same longevity as the ‘Johnson ‘ole’ does but very, very quickly.

He's already working on what becomes the theatrical production of, I would say, of the whole war.

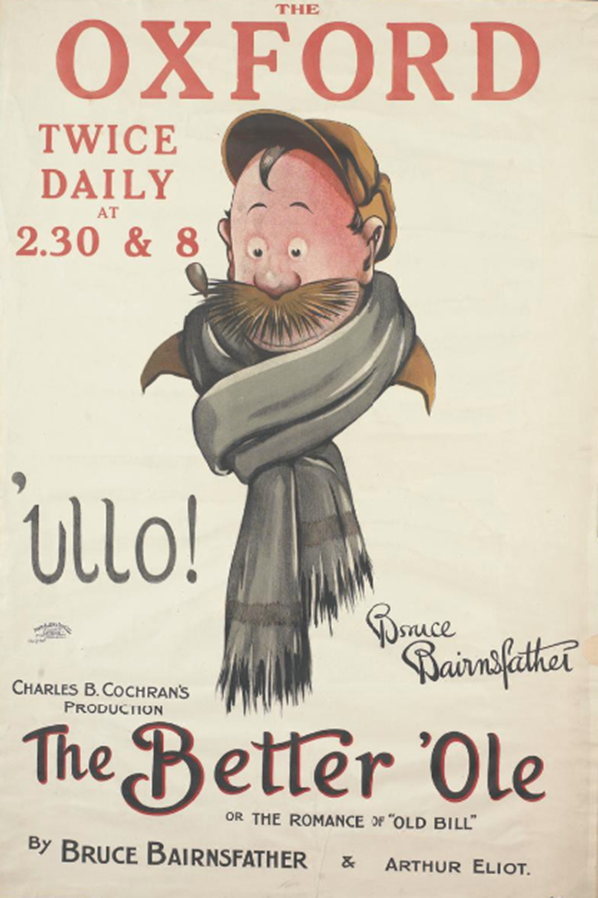

It is seen as THE biggest hit of the war - certainly in terms of a play that tackles the war itself. That is the play ‘The Better ‘Ole’ which premieres at the Oxford Theatre, which has been a Music Hall which gets reclassified as a theatre, for this production - and that opens on the 6th of August 1917.

TT: So tell me about ‘The Better ‘Ole’. What was it a comedy or is it a tragedy? What type of play was it?

Helen: So it’s a little bit of everything, it draws on a number of different genres as reviewed at the time. It is described as being structured in two explosions, which we can read as acts - seven splinters, which we can read as scenes - and a gas attack.

I think what's really interesting is that Bairnsfather takes the structure of the experience of being a soldier at the front line and he replicates it on stage. So it begins with his three Tommy's: Old Bill, Bert and Alf who are behind the line enjoying some theatre and in every scene they are getting closer and closer to the front line. And what's really interesting about it is that - in a way - nothing really happens - until the very end when there's this gas attack and we'll sort of have a melodramatic ending where Old Bill saves the day.

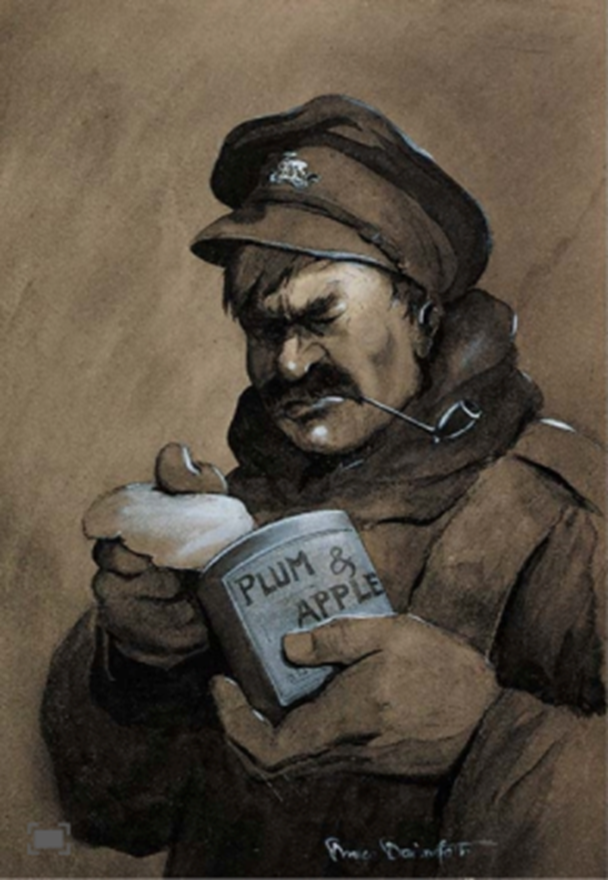

But for the majority of the production, what we have is these three Tommy's - standing around, chaffing, making jokes singing some songs, receiving letters, receiving newspapers - and actually all the comedy and all the references - are seen by soldiers who’ve come to see the play, and is seen by people at the time as being very realistic. So they absolutely draw on references, that are both coming out of the cartoons, that Pip has highlighted - but also are about references, that are drawing on references that everybody is familiar with, so jokes about plum and apple jam, jokes about getting stuck in the mud, being like flypaper - all these things that really resonated for people at the time. So it is comic but it's also seen as people - seen by people - as actually being very heart-rending - so you get lots of stories about people going to see it and weeping but feeling better for it.

TT: Is the play slightly politically incorrect by today's standards?

Pip: Weirdly, no, not massively.

Helen: You don’t read it and go “mmm, that’s really … “So there is no, whereas some plays, there are lots of racial terms that you just go, how do I just deal with putting that online. There is nothing like that, largely because there aren’t any non-white characters in it. There are a few female characters - who appear briefly, and are the subject of Alf’s romantic attentions, but there is nothing inappropriate there.

Pip: There is a little about Old Bill’s wife.

Helen: There is a domestic angle to it. It is the three of them - like a little family, getting through this experience - and if anything, what stands out for me is the bathos of it … so you get this moment where they're waiting for letters. Everybody else gets letters, but they don't get any letters - and this this kind of sadness and at least it and read the papers together - and there was a kind of - domesticity to the experience of life at the front, which I think connects to what a lot of men said, about it as an alternative to home life.

Pip/Helen: totally, forced to do this ... I mean that's really a very minimal female presence in it. There's no non-white present in it. So this kind of not much opportunity to be politically incorrect in a way.

So it is quite interesting in that sense because a lot of the other plays - there are quite a few aspects. I mean the other thing about the ‘Better ‘ole’ is … you don't see the enemy in it. So most first world war Place certainly had melodramas. You've got, you know stereotypically dastardly German villains, you know, terrible Prussian officers here are twiddling their moustaches - and you know, looking incredibly evil with these wonderful accents that are written in the script for the actors.

So you've got that - and you've got this - something I'm writing on at the moment - this awful representations of Germans, but which is also very pantomimic - and it's really fun for the actors to play with. And then you've got you know heroines who have been raped - and who have been dragged off - and all sorts of awful threats.

And very often the Censors will be,

“You're going too far, you know. You can imply that, but you can't show anything"

And that sort of thing. But because the ‘Better ‘Ole’ is set in a time at the Frontline - It's in that male world. Actually, it's noted at the time as being a production which doesn't have a Red Cross Nurse in it, or a German - and that's really unusual.

TT: So what's the relationship between the stage production and the cartoons? How does that develop over the war?

Pip: The stage production in many ways uses so many of the cartoons that the public would have recognised. Bairnsfather had been producing cartoons since early 1915 and he's been putting a production on in 1917.

There's a whole catalogue of cartoons that are used.

So I think you mentioned earlier, ‘Where did that one go’.

This is one of his first initial ones he puts out there - where the part of the barricade that they're looking at has just disappeared next to them.

There are other cartoons you can see being referenced throughout the play.

There is the explanation of why Old Bill always has a balaclava on - and he explains by writing a letter home to his wife, ‘please thank the vicar's wife for making those socks. I'm using one of them as a balaclava for my head and the other is where I keep all my clothes’.

So you're suggesting - that there's the connection to the war where we know that lots of women are at home knitting socks - even if they had never knitted before in their lives - and the sense that ... perhaps they might not fit ... was coming through quite nicely with - just through the cartoon that people understood - but also then making a reference to it.

There is the song in the play about plum and apple jam - and that is the 'Eternal Question' - that Old Bill is always asking - the eternal question is, “when are we going to strawberry?” Because they didn't have that - plum when apple was much easier to make as it was more readily produced - and strawberry, there was only a small season in England for strawberries. So therefore you didn't get them - particularly often.

So there's all these references to other cartoons, but he also makes reference to other elements of cartooning that were in the world people would have known about. There is a lovely moment where the Sergeant is walking across the stage with a box of stuff. He puts the box down, looks up, lights his cigarette, an explosion goes off in the background and he goes “Alf a mo’, Kaiser”, picks up his box and walks on again.

Now, for most people, this would make complete sense - because of Bert Thomas’s cartoon, ‘Alf a mo’, Kaiser’ - of a soldier lighting a cigarette - is he most famous one for producing funds to buy cigarettes for soldiers throughout the war.

So there's all of these connections that just make sense of problems of that time.

Helen: And I think it must have been so exciting to go see it, to see all these kinds of familiar cartoon and images brought to life in front of you. So there would have been a lot of pleasure in getting the jokes - and kind of being in on the joke for the audience as well, which I think explains in part some of its popularity as well because it was just a phenomenal hit.

TT: So who actually goes to see the play, and what sort of numbers are we talking about?

Helen: We are talking about - it's comparable to The Battle of the Somme Film - in a theatrical context. So, the production at the Oxford Theatre in London is entirely sold out - and there were wonderful cartoons, which appear in the papers, of all the queues of people who are desperately trying to get in to get tickets. Within one month Charles B. Cochran, who's the producer, has decided that he's going to produce multiple touring versions.

So within a month of touring version comes out. And what point he is going to set up touring tents so that lots of people get to see the play. It does not come off for lots of reasons. But, it actually goes on tour.

So throughout the rest of the war, from October 1917 onwards, you have three productions being toured at the same time. You’ve got the London one, and you've got two regional productions going all over the place. And many of those go back more than once to the same theatre - and people go to see it more than once - and then actually you have a film production, as well.

So the film comes out in 1918 - and people seem to have gone to see the film one night, and then see the theatre production the next night. And whether they are doing that because they want to compare and contrast or they just can’t get enough, who knows?

Pip: The cinemas would put the film on next door to a theatre so they were buildings next to each and there were queues out of both.

Helen: And I think what is important is how soldiers on leave went to see this - it really captured the popular imagination, they were taking their mothers, they were taking their sweethearts. And there were lots of reports of - Cochran particularly, overhearing people saying, as they're leaving the theatre, you know, “Don't ask me what it's like, that's what it's like … and I'm alright”, because, actually it's quite a reassuring production. Although it seemed to show the reality of the war, it is a sanitised, comforting, reality of the war but it's very much used. It's a sort of its family viewing in a way. I think.

TT: How does officialdom view the cartoons and the play? Do they generally support them and think they're positive to the war, or do they see them as slightly subversive?

Helen: Certainly in terms of the theatre, there is no real response officially. In order to be produced up until 1968 every piece for theatre had to have a license from the Lord Chamberlain's Office anyway. So it is clearly seen as something as good for the public moral.

Pip: This carries on after the war, Bairnsfather, although he is forgotten about in many ways about for a while, he comes back in the Second World War, as an Officer cartoonists, not under the British authorities though. It's the Americans who take a much better view. So there are other nations that have noticed the morale boost that he has provided for its soldiers - and they want him in the same capacity to come back in, and bring morale - that is a positive thing

TT: And does the play continue to be popular into the 20s?

Helen: No, not really. It is very much of its moment. So it does tour internationally. And it does very well. It goes over to America. It goes to India. It goes to Australia. I think. So it has a huge international spread, but - about a month after the war ended, the British productions shut down - and then there are attempts to do sequels, which really don't go down very well in the 1920s. So it's actually something, that although it is a massive, massive hit - it is so much of its moment and is so connected to the popular culture of the time - and to feelings about the war - and actually to that morale - that Pip’s just mentioned - that it really doesn't have the lifespan beyond the war.

TT: Do you think that the meaning of the cartoons changed? Hey does ‘the ‘ole’ have a different sort of idea behind it nowadays?

Pip: I’d say it very much finishes within a few months of the war. In contrast, the cartoon has quite a considerable longevity. It comes in fits and starts as we go through the following century.

There are more copies of ‘The Better ‘Ole’ … not only by Bairnsfather, who reproduces the cartoon several times, just with different people in the ole - its working so he re-uses it.

Other artists borrow from him, either the title or the image - and that is reproduced quite a few times - after the 20s. In the 1920s there was hardly any reproduction. 30s, there's a few more. 40s again not quite so much, 60s there’s a couple - and ‘The Better ‘ole’ does go to the moon. 1967, the better role is on the moon, when there are debates about whether the military should have control of various things so clearly the better old on the moon and that's that's out of the way. Why not? Everything is safe there. 70s again far more. 80s we have a lovely reproduction with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher in the ‘ole because who else are you going to put in there at that particular point in time and about 1984.

And then coming into the most recent years - 2014, Michael Gove was put in there - ironically, straight after he said that we shouldn't teach the First World War using Blackadder - because clearly that doesn't make any sense - but I don't know whether he realised quite the context of how he was put in the ‘ole or what that meant.

So the meaning perhaps changes quite a bit, but the idea is still there. So it's an ongoing feature in those terms that people recognise the idea of having a better ‘ole - and maybe there isn't one. But don't necessarily know the context of where it came from - in order to understand the backhanded comments - so there was a patron with that one.

But, you know, it goes up to more recent times, as well - 2017. Donald Trump did find himself in the hole. And last year we had the entire Brexit Party thrown in there. So, you know anyone, who is a key member of politics in Britain were just chucked in the ‘ole - because there's a lot of times where it has been reused for different reasons and in different contexts.

TT: You've shown that the nature of the ol is a new survey how many people are aware of its history?

Pip: The original history, probably very few in real terms - I know it's particularly. Valmai and Tonie Holt, Mark Warby (@BBairnsfather) is ‘Mr Bairnsfather’ himself online. You can go through Twitter you can find every cartoon he has produced, throughout the Centenary, and on the date and at the right time, which is a fantastic skill; Lucinda Gosling has also written a book about him. But I can name those people there are not very many. For the origins, there is very little awareness and knowledge, there is a professional awareness, memory almost, through the cartooning world.

A lot of the images that I have just spoken about: different people have been put in the ‘ole. Definitely Peter Brooks, has used the ‘ole quite a lot of times. So he was doing it in 1984. There are certain cartoonists, Keith Brooks of the Times, has reproduced the ‘ole a few times. Others have reproduced it a few times going through the decades and century … there are certain professional memories do hold, but not the broader public.

TT: Helen has the better ol actually been revived as a play at all?

Helen: There was an amateur revival at the start of the centenary, but beyond that, no. Which speaks to its popularity at the time was so much bound up with the contemporary references - and it is really hard to get back to that. So whilst some of the war time productions, particularly such things as ‘The Man Who Stayed At Home’, a December 1914 massive hit - a Burty Worcester spy … things like that, have a lot more potential to be re-staged to day, it taps in I guess, to that revival, for the fascination people have around the 1920s, and that culture around Agatha Christie, spies and crime, ‘cosy crime’, as it is now called …but the ‘better ole was fundamentally, every aspect of it was referencing the cartoon or the experience of the war. That is a wider context for the audience that we just can’t get at.

Pip: We both went to see the reproduction of ‘The Better ‘ole’ on the stage and there were moments when I thought that was really funny and I thought don’t laugh now because it is just an inappropriate time. But it has now become an inappropriate time, whereas 1917 everyone in the theatre would have been laughing at those jokes, because they known and understood the context. Whereas today it didn;t have quoite the selling power, which is a bit of a shame.

Helen: It was interesting to see I think and see that gap between even on knowledge. But the fact that I'm not living through that fact that it's not kind of an important experience for us compared to people at the time we can go intellectually are really interesting and it's funny on that level - but actually that difference between, something. I guess. It's a bit like being a political comedy - and things today that are so much, you know, so responsive to what's happening even week by week - and that if we look, you know, look back a hundred years times actually that comedy won't work in the same way. I think that's happening with ‘The Better ‘ole’ as well.

TT: So what do you think ‘The Better ‘Ole’ in terms of its cartoon and its theatre production tells us about culture during the First World War?

Pip: The way people understood humour, and the way they are learning through the humour. There are a lot of Bairnsfather trying to set up like other cartoonists, trying to teach, so the didactic element in these images - you see a character doing something, you know, who shouldn't be sound that silly thing, but its funny when someone else does a thing. So there's a learning impact through that as well. The humour is - of its time in many ways - but then humour does go around the cycles. So perhaps that's why we can understand it and at the same time can see that it's a bit detached from where we are now.

Helen: I think what is interesting in terms of theatre production, is the way in which, I supposed theatre more generally gives you an insight into how people were responding to what was happening around them. So as a cultural historian, I'm really fascinated in the ways that things like literature and cartoons and poetry etc. But theatre is often left out of this, and the way in which we look at these moments of performance which were so hugely popular for people at the time: What's that tapping into? What does that provide people with? - and when we look at the reviews of the productions and what contemporaries are saying about the experience of going to see this play, we can start to see the way in which it does, genuinely, provide a means by which they can kind of mediate their experience. They can cope - it provides a way of coping with the horrific experience of going through the war. You know, the horrific experience of having your loved ones away and not knowing when you'll see them next, and worrying about them. And so it kind of gives us that way of getting experiences of the historical past, beyond the facts and figures, I guess. And also the different ways in which aspects of the War were challenged as well. So, you know, that sort of didactic element - and the political edge that there is, to both the cartoons and the play as well. It's you know, it's ground up. It's coming from the men who were there, who’d seen it and I think that’s a lot that comes across in the commentary as well : this is coming from a man who's been there who's in the trenches, he is one of them. It's not coming from playwrights who’ve sat at home and don't know what it's really like. So that sense of a ‘voice’ - a voice of the men, of the Tommy, is really important.

TT: And finally, where can people learn more about Bairnsfather’s ‘Better ‘ole’ - and your work?

Pip: There’s lots of bits of pieces that are out there, certainly, the Holts books, are the easiest way of accessing the Great War.

Helen: There will be a ‘Cambridge Companion to the Theatre of the During the First World War’ which will be coming out in the next few years that I am editing. For immediate access, for people who are interested in theatre and its response to the war, I’ve been running over the last few years called the Great War Theatre Project, which people can find at www.greatartheater.org.uk - and that provides everyone with a database of every single play, including the ‘Better ‘Ole’, which was produced in England, Scotland and Wales throughout the First World War. So we've also got a lot of blog posts up there with all sorts of different aspects of theatre and the war and it does, I think, what one of the things behind that project was really about - bringing to life this overlooked aspect of cultural history, and First World War history, which both Pip’s work and looking at cartoons, and looking at theatre, is very much about taking a different angle on the First World War and thinking about what that different angle can offer us in terms of our understanding of the experiences of War. So yeah, I'd certainly recommend having a look at the website and get in touch with us, as well, because we're both always really happy to hear from people who might have questions or might have different bits of information which tap into what we're working on.

TT: Ladies. Thank you very much for your time.

Pip and Helen: Thank you.