A Christmas Party then Tragedy : 30 December 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Christmas Party then Tragedy : 30 December 1915

The band of the Royal Marines played, a film show ran and then tragedy as a series of explosions ripped through HMS Natal on the afternoon of 30 December 1915 in the Cromarty Firth.

The ship sank within 5 minutes with the loss of 421 lives, some of them being the Captain’s invited guests including a local family and nurses from a nearby hospital ship. The toll of civilian casualties may well have been greater had not a strong wind sprung up and kept many of the guests onshore.

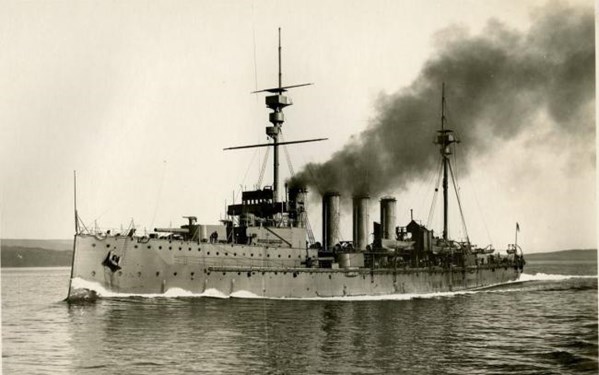

HMS Natal was a Warrior-class armoured cruiser built by Vickers, Sons and Maxim Ltd. Shipyard in Barrow. She was launched in September 1905 and entered service with the Royal Navy in 1907, being assigned to the 5th Cruiser Squadron. The Natal displaced 13,550 tons, which was the same as many battleships of the time, was heavily armed with 9.2 inch main guns and had a top speed of 23 knots, faster than most contemporary warships of the day. The ship had been funded by the South African province of Natal in appreciation for the protection given by the Royal Navy.One of its first tasks was to escort HMS Medina to India in 1911 and afterwards it was appointed the royal yacht for the new King George V. In 1912 it carried the body of Whitelaw Reid, US Ambassador to the UK, to New York, resulting in the nickname Sea Hearse.

In 1909 Natal was reassigned to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron, joining the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow at the outbreak of war in 1914. After rejoining the 2nd Cruiser Squadron in January 1915, following a brief refit at Cammell Laird in Birkenhead, she sailed from Scapa Flow to the Cromarty Firth.

On the afternoon of 30 December 1915, a party was taking place on board. This included Captain Eric Back, his wife, along with other officers and wives, three nurses from the hospital ship ‘Drina’ and civilians from the surrounding area, including the factor of Novar Estate and his family. Meanwhile, more than 100 of the crew were ashore at a football match in Cromarty.

At just after 3.20pm, a huge explosion occurred in the ammunition hold of the ship, setting off fires and other explosions throughout the ship. The first external sign of a problem was a signal sent to the anchored fleet’s Flag Officer at 3.25pm saying simply “Ship on fire”. A copy of that signal and others from the fateful day can be seen in the Invergordon Naval Museum. Within five minutes of the initial explosion, HMS Natal had capsized. Many of the crew, including the captain, his visitors and two of the fitters, perished in the immediate aftermath of the explosion, while others managed to survive by swimming away from the sinking ship. A further signal to the Flag Officer from the nearby HMS Blanche timed at 3.45pm said simply: “Natal sunk.”

Many years later, an eyewitness account appeared in the Dundee Courier which indicated that a huge yellow flame shot up over the masthead of the Natal. Two explosions followed, the ship listed to starboard, then gradually heeled to port and then sank. The newspaper also recounted that

‘A retired Naval officer who was on board states that if the explosion had occurred five minutes later none of the guests would have lost their lives. The party was rapidly drawing to a close and at 3.20pm the Captain sent up orders for the launch of another boat to make ready to take off the visitors. The officer was just getting ready to see them up the hatchway when the first terrible explosion took place in the after magazine. The whole party and the ship’s band were instantly wiped out. “I was thrown on deck” he said. “The smell of cordite was overpowering and nobody seemed to realise what had taken place.”

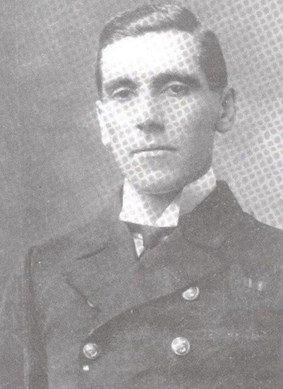

The list of dead includes Commander John Hutchings’s wife Mabel, Mrs Violet Back and Mrs Bennett, the wives of Captain Eric Back and Engineer Lieutenant Frank Bennett respectively. All three husbands also died. The factor of Novar Estate, Evanton, John Henry Dods and his family all died in the disaster.

Above and below: Captain Back and his wife perished. Although their two children, Diana and Eric, were not on board the Natal.

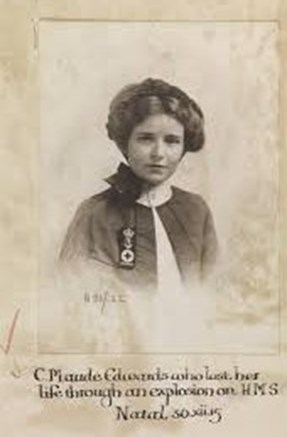

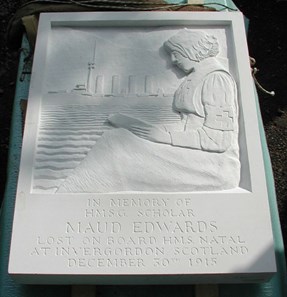

One of three nurses from the Drina to be lost was Maud Edwards (image below), who had attended Harberdashers Monmouth School. A memorial was erected at the school following her death.

Over the next few days, bodies of those lost on the Natal washed up on the shores of the Firth; these are buried in Invergordon and Cromarty.

Above: The Natal graves at Cromarty Cemetery which overlooks the site of the tragedy.

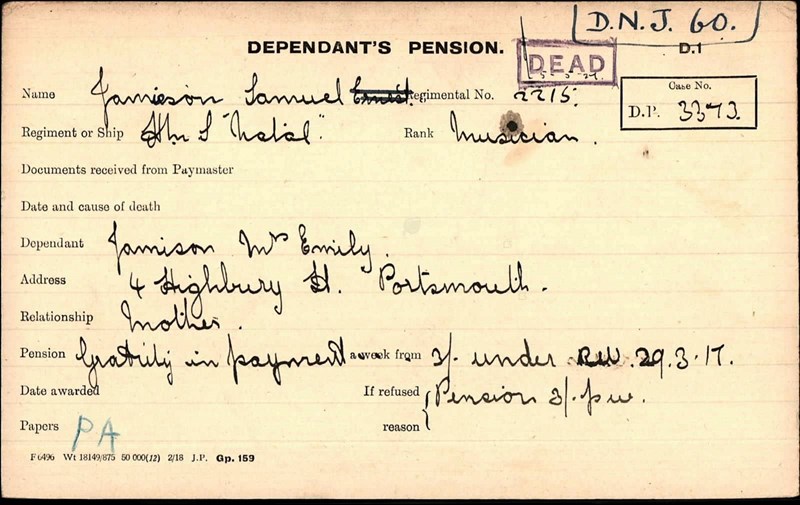

Musician Ernest Jamieson, from Portsmouth, was one of the members of the RM Band on board the Natal. His body was never recovered and he is commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

In the days following the disaster, rumours abounded locally about sabotage or submarine attack, however an Admiralty inquiry concluded that the cause of the explosion was faulty cordite.

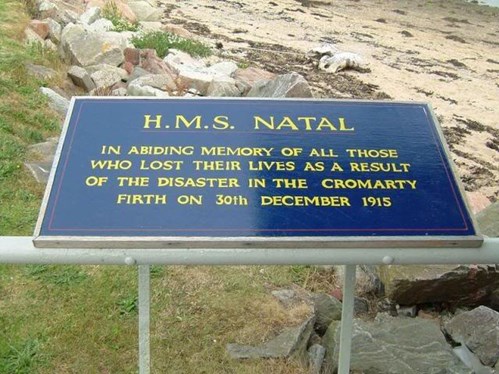

The ship was salvaged in the late 1930’s and then blown up as the wreckage was a danger to ships in the area. A buoy in the Firth marks the site of the sinking of the Natal. A memorial to HMS Natal was erected in 2015 on the shores of the Cromarty Firth (image below).

Above: The upturned hull of Natal in Cromarty Firth

Below: The Bouy marking the site of the wreck today.

The Natal was remembered for many years afterwards by Royal Naval ships, which - on entering and leaving Cromarty until the Second World War sounded "Still",[1] and for officers and men to come to attention as they passed the site of the wreck.

Article by Jill Stewart, Hon Secretary, The Western Front Association

[1] The 'still' (usually a whistle) is used to call the crew to attention. This would be done, for example, when two warships meet, the still being piped as the junior ship salutes the senior ship.