A draft of 100, all boys from the Kings Liverpool Regt

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A draft of 100, all boys from the Kings Liverpool Regt

Most people seeking to trace the steps of a soldier who served in WW1 will run into the same dead end that I did when I was trying to follow my father's journey through that war. His service record, the document that would have provided the necessary details, no longer exists because most of them were destroyed in the London blitz of 1940 - and that brought the investigation to a halt before it had really begun.

But it occurred to me that it might be possible to reconstruct his missing record using digital technology once sufficient information became available online and indeed, with the increasing pace of digitisation in recent years, that has proved to be the case.

This investigation, conceived in 2002, before any military documents were on-line, took 15 years to complete, but most of that time was absorbed waiting for data to become available in digital form. The first step, analysis of Medal Index Card data, couldn't begin until 2008 and the last piece of the jigsaw didn't come to light until 2017. Starting today, when so much data is already on-line, the basic steps could probably be completed in days or even hours.

I've been astonished at the results. Beginning with very little hard evidence, it has been possible to build a comprehensive and detailed narrative of my father's wartime service that goes far beyond my expectations at the start of the project.

I thought I should set down the story to try to help others to investigate their own heroes.

The beginning

This story began in 2002 with a man and a mystery. The man was my father who served in WW1 and, as part of unravelling my family history, it was important to me to find out about that pivotal period in his life. The mystery arose as soon as I started to gather together the facts and the dimly recalled shreds of memories from my brother and sisters.

There was very little to go on. Like most men who came back from that war he didn't talk about it, but just occasionally something might slip out if you were attuned to catch it. We knew he'd been gassed but little more than that. Then long after he'd died my mother told me he'd been in hospital on the day the Armistice was signed and for a year afterwards and, linking gas, hospital and Armistice day together in my mind, I’d assumed he’d been gassed in the final days of the war (quite wrongly as it turned out).

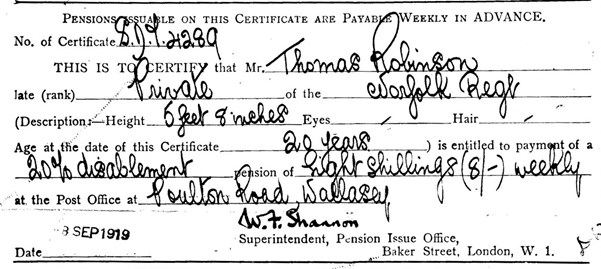

There were just three pieces of hard evidence, an undated photograph of a proud young man in uniform (Figure 1), his medals (Figure 2)and a fragile sheet of paper - his Certificate of Identity (Figure 3) which was stamped by his local Post Office every week for a year from 10th Sept. 1919 to show that he had drawn a 20% war disability payment of eight shillings.

Figure 1: My father, Tom “Robbie” Robinson. Photo taken in New Brighton. The added blow-up shows his Kings Liverpool Regiment cap badge

Figure 2: My father’s British War medal inscribed “49085 PTE. T. ROBINSON. NORF R”.

Figure 3: He received a disability payment of eight shillings a week for a year after discharge.

Figure 3: He received a disability payment of eight shillings a week for a year after discharge.

The mystery that I couldn't explain, and that intrigued me more and more as time went on, was the glaring mismatch in those clues. The photo showed my Dad in the uniform of the Kings Liverpool Regiment (the cap badge is unmistakable) yet both the medals and the document appeared to indicate that he served only in the Norfolk Regiment.

I wanted to know why there were two regiments? What happened to him in France? and where and when was he gassed?

What I needed was his service record, which in 2002 meant a visit to The National Archive in Kew (then known as the Public Records Office)[i] but unfortunately it wasn't there, it had been destroyed in the 1940 London blitz.[ii]

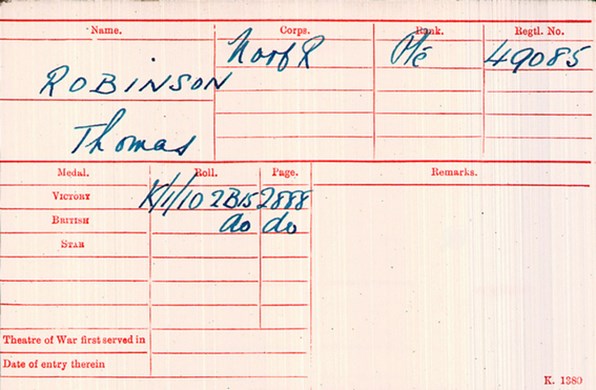

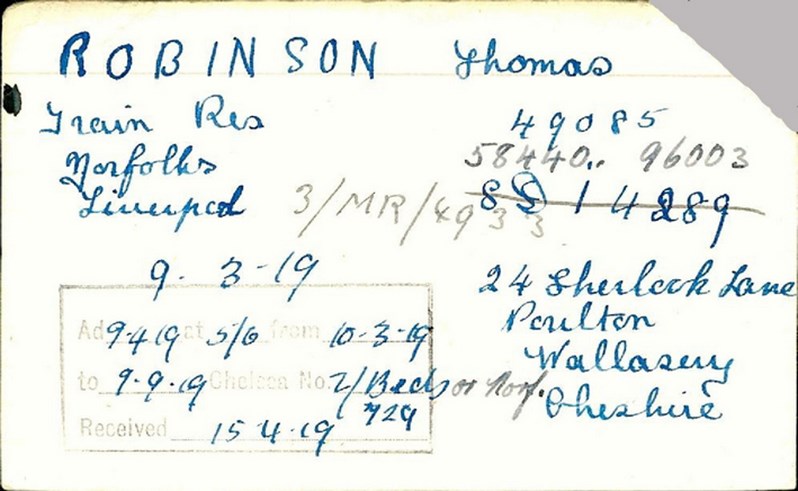

I did however find his Medal Index Card (Figure 4) and although it only confirmed what I knew already, it was encouraging to find the first new evidence of his service.

Figure 4: His Medal Index Card (MIC) shows his medal entitlement - the Victory and British War Medals

I learned too that the MIC collection contains around five million entries and is the most comprehensive source available of the names, numbers, and units of the men who served in WW1. It was obviously a vital source, but at that time its content was one dimensional, in the form of images indexed only by names, and thus the index could only be explored if an individual's name was known. I'd need to access the data from more than one dimension in order to move forward - and it took some time before that became possible.

The basic idea was simple. I reasoned that if my father's service record no longer existed then, if I could identify men who joined the same regiment at the same time, perhaps some of their records may have survived - and if so, they might throw some light on what happened to my Dad.

Identifying Contemporaries

The first step was to find the names of men who enlisted at the same time, and this became possible in 2008 when MIC data was digitised and came on to The National Archives (TNA) website.[iii] The MIC database can now be accessed from a number of providers, [these Medal Index Cards are able to be viewed using the WFA's Library Edition of Fold3 via WFA members' personal log in: Ed] but (at the time) I found the TNA search facility the most appropriate for this purpose.

Figure 5: Search box of The National Archives WW1 Medal Index Card database.

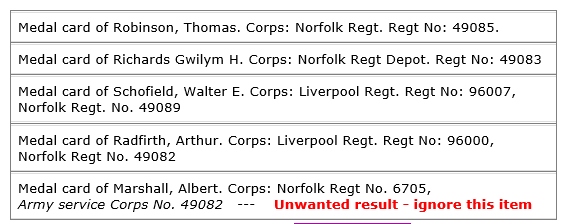

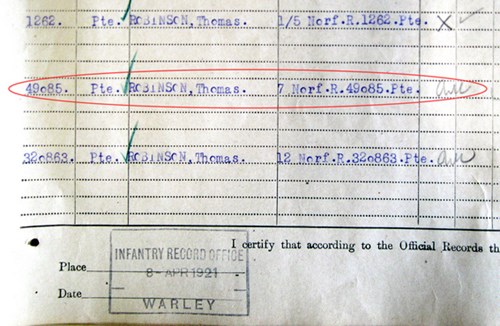

Crucially, the National Archives MIC database allows "wild card" searches which will provide up to ten adjacent names in one search. By leaving the name slots empty on the search page (Figure 5), substituting a question mark (?) for the last digit of my father's service number in the [Regt. number] box, and entering his regiment - "Norfolk" - into the [Corps] box, I was able to retrieve the names of the ten soldiers of the Norfolk Regt. who had numbers in the range 49080 to 49089 (Figure 6), and there is no charge for that. However, I found a minor quirk in the search engine which means that if a man served in the Norfolk Regt with a number outside the search range but at another time served in a different regiment with a number inside the range - his details will also appear in the list - but it's easy enough to spot these unwanted results and ignore them.

Figure 6: Extract from the first TNA Medal Index Card search. Results appear in random order - I took it as a good omen that my Dad happened to appear first in the list.

The search results come up in random order and any pattern in the data is not immediately apparent. I wrote down the list of names, numbers and regiments and then repeated the exercise by searching for the 10 numbers below and above by entering 4907? and then 4909? into the search box.

I then had a list of 30 names, numbers & regiments and some patterns began to emerge. Firstly, it was obvious that there were two regiments involved - several of the entries recorded the Kings Liverpool as well as the Norfolk Regiment. Secondly, it seemed that if the random list were to be arranged in Norfolk Regiment numerical order then the Kings Liverpool Regiment numbers might also fall into numerical sequence and the names might fall into alphabetical order.

It was almost as if I'd stumbled on the equivalent of the “Rosetta Stone” - the ancient Egyptian slab on which a text had been recorded in three different languages - the discovery that led to the decoding of Egyptian hieroglyphics. In my case it was a triple data sequence, so that gaps in any one sequence might be filled by reference to the other two, and I hoped it might lead to decoding my Dad's war service.

So I typed the list into an Excel spreadsheet[iv] and used its Menu Bar > Data > Sort facility to arrange the data into alphabetical order - and sure enough, the Norfolk and Kings Liverpool numbers each fell into a perfect numerical sequence (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Extract from the initial 30 name / number / regiment sequence after rearrangement into alphabetical order.

There were some missing Kings Liverpool Regt. numbers among the 30 names, but I knew that my Dad, Tom Robinson had been in that regiment - his photograph proved it. Now it was clear from the numerical sequence that his Kings Liverpool number, although missing from the medal index card, must have been 96003.

That solved the mystery of the mismatch of regiments between his photograph and his documentation - but much more than that - by the same logic I could deduce all the other missing numbers - John Thompson's would have been 96010, George Thornborrow's 96011 etc.[v]

The symmetry of it all so intrigued me that I temporarily set aside my original objective of finding service records to dig deeper into these name and number sequences, simply to see where they would lead me.

Extending the search and analysing the numbers

Thus far, I had obtained a coherent name/number/regiment sequence for 30 men from 49070 Jim LITTLER to 49099 Robert WHITE and I wanted to find out how far the sequence would hold.

I began to explore numbers higher than 49099 by entering "4910?" and "Norfolk" into the TNA Medal Index Card search box (see Figure 5) - but there were no results and four further attempts, taking the search up to 49150, were equally unsuccessful. It was clear that the sequence had run out, and that 49099 Robert WHITE was the last man in the list.

Then, using the same technique at the lower end of the list to explore numbers less than 49070 Jim LITTLER, I determined the lower limit of the sequence. The first man was 49000 Frank COLEMAN - beyond him searches for the next 50 numbers yielded blanks.

Figure 8: Extract from the Norfolk Regiment 100 name / number sequence

This gave an alphabetic list of 100 names with consecutive number sequences (Figure 8) in both the Norfolk Regiment and the King's Liverpool Regiment (although 52% of the Kings numbers, those in brackets and in colour, had been derived by deduction.)

At this point, although the Norfolk numerical sequence was complete, the alphabetic name sequence was not - there were no A, B or Y surnames - and it seemed logical that there should have been some. This was where the "Rosetta Stone" effect came to the fore, because although the Norfolk sequence had run out, I was now able to use the deduced Kings Liverpool numerical sequence to move the investigation forward and complete the alphabetic name series.

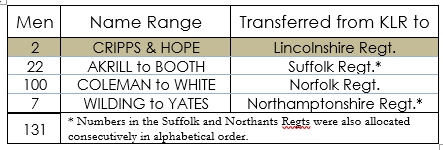

Figure 9: 131 men of the Kings Liverpool Regt transferred to other regiments.

The analysis technique was exactly the same as that used for the Norfolk regiment, except this time searching the TNA database (see Figure 5) with "Liverpool" in the [Corps] box and "9591?", "9601?" etc. into the [Regt. number] box. These searches tied up the loose ends.

The analysis revealed a complete alphabetic series of names from AKRILL to YATES with consecutive KLR numbers. Here was a coherent group of men of the Kings Liverpool Regiment who at some time were split up and transferred to other regiments. (Figure 9).

Two of the names, William Cripps and Fred Hope, don't fit into any pattern and I suspect that they were picked out first - perhaps because they may have had special skills sought by the Lincolnshire Regt. - but the remaining 129 appear to have been subsequently lined up in numerical or alphabetical order and simply counted off as required.

I now had a list of 131 men who had been allocated numbers in the Kings Liverpool Regt. around that of my father - and I knew their names, their regiments, and their service numbers - all the information needed to begin the search for service records.

Pension Record Cards

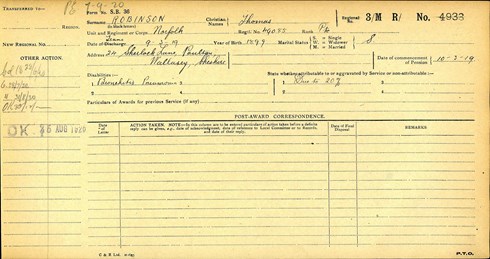

At a later stage of this research, when I had uncovered many of the facts, I discovered a document that confirmed all of the investigation work that I had done up to this point.

It came from a (then) new source of WW1 records which had come to public notice in 2013 after The Western Front Association had saved from destruction a large collection of WW1 Pension Record Cards. The records consist of about 5 million index cards and associated ledgers which had been created after the war to assist in the administration of war pensions. They comprise: –

- almost 1 million records for Other Ranks who had died.

- over 1 million records for their widows and dependents.

- over 2½ million records for Other Ranks who had survived sick or wounded.

- about 150,000 records for Officers who had survived and their widows.

- about 5000 records from Merchant Navy personnel.

The records are in the custodianship of The Western Front Association and are in the process of being made available for on-line access via the WFA's partner Ancestry.com on their 'Fold3' web site. However, at the time of this investigation the archive was only accessible manually on payment of a search fee.[vi]

Figure 10: My father's Pension Record Card. [Editor's note: this card is from the 'soldiers survived' set. This set is (at October 2019) yet to be published online, but should be available during the course of 2020]

My father's card (Figure 10) gave me little new information but was invaluable in confirming for the first time all of the investigation and deduction that had gone before.

It officially recorded his Training Reserve Battalion number (58440), his Kings Liverpool number (96003), and his Norfolk number (49085) all on the same document (although they are in the wrong order!).

Finding Service Records

The fact that any soldiers’ papers survived at all after the fire in the blitz of 1940 is little short of a miracle. Those who made the decision to preserve the charred and waterlogged residues deserve our gratitude, and those who painstakingly separated and catalogued the remains merit our admiration.

The current database of surviving service records[vii] is a digitised collection of pages or parts of pages, many of which have been rendered illegible to a greater or lesser degree by the fire, the smoke, and the water from the firemen's hoses. You may only find part of a name or a fraction of a service number or date of birth, and it may, in some instances, require a good deal of study to identify the man behind the fragments. Searching for a single service record is fairly straightforward but working on a long list of names can become a laborious task, especially since neither "Service Number" nor "Regiment" seem to be valid search terms for filtering results in the available sources. A common name will yield a lot of results which have to be individually checked for a service number - and that is very time consuming.

To focus my search, I concentrated on the Norfolk squad of 100, because my father was number 85 in that group, and I began the search with the fourteen names above him - it yielded two service records. Then I started investigating names from 84 downwards - and by the time I'd done seven searches there were another two records. After that however, there was a long barren period when no new records came to light. I became a little disheartened and decided to analyse the four records I'd already uncovered before completing the remaining searches.

I found that all four service records related to men who were killed in action, and that triggered another thought - was it merely coincidence, or was it another pattern?

Once again, I temporarily stepped aside from the job in hand to investigate the idea. It was partly to give myself a break from the grind of sifting service records, but mainly because I knew of a quick and elegant way to check it out.

Exploring the CWGC database

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission database of those who died on active service[viii] is another one-dimensional name-based collection that is designed to reveal details of a single individual, and it does that job well, but it can't be used effectively to research groups, e.g. the losses suffered by a Battalion, a Regiment, or group of Pals etc. - and that seems to be a sad neglect of the power of digitised records. Fortunately, there is a solution.

The website "Geoff's Search Engine" [www.hut-six.co.uk/cgi-bin/search1421.php] by Geoff Sullivan, allows a multiple service number search to be conducted very effectively. Access is free, but the site depends for its survival upon donations from those who use it.[ix]

Figure 11: The search box from "Geoff's Search Engine"

For my purposes, it was sufficient to enter "490" into the [Service Number] box, since all the numbers I was interested in began with those three digits in the range 49000 to 49099, and to select "Norfolk Regiment" from the drop-down list in the [Regiment/Corps] box - leaving all the other boxes blank (see Figure 11). The search yielded 35 names but 12 of the service numbers didn't begin with "490", they contained that sequence elsewhere in the number - e.g. "24900 Pte William Wright" - but once again it was a simple matter to identify and ignore these unwanted results.

The refined list identified the names of 23 from the contingent of 100 Liverpool-Norfolk Regt transferees who had been killed in action. I already had service records for four of them, so I concentrated my search on the remaining nineteen names and this quickly yielded another five sets of papers. Later, I completed the search on the remainder of the 100 Norfolk Regt names, but no further service records turned up.

It seems a little odd that the only Norfolk Regt. service records to come through the 1940 fire belonged to men who had been killed in action. The only plausible explanation that occurred to me was that for some reason their records must have been stored separately from those of men who survived the war, in a location subject to less severe fire conditions.

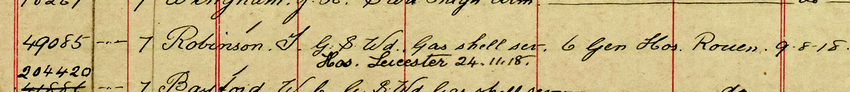

Figure 12: My father's Medal Roll ledger entry showing 7th Bn Norfolk Regt.

One other piece of vital information that dropped out of the analysis of the CWGC data was the identity of their battalion at the time they were killed - 21 of the 23 Norfolk Regt casualties were listed as being from the 7th Battalion. I therefore drew the conclusion that my father too had been assigned to the 7th Battalion and this was later confirmed by a visit to the National Archives to check his entry in the Medal Roll Ledgers (see Figure 12) using the code on his Medal Index card (K/1/102B15 page 2888 - see Figure 4) to identify the correct roll volume and page number. (These Medal Roll Ledgers are now available on-line which makes the whole process much easier.)

So, this study of the coherent group of 100 Kings Liverpool to 7th Bn Norfolk Regiment transferees had yielded 9 service records - and they tell a consistent story.

Analysis of the Service Records

All nine service records indicated birth dates between June and September 1899 and origins mainly in north Cheshire and south Lancashire. My father fits neatly into these criteria, having been born in Liverpool on 30th June 1899 and resident from the age of eight in Wallasey, Cheshire.

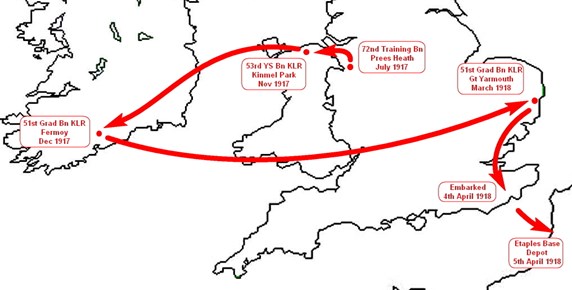

In July 1917 the new recruits, all having just passed their eighteenth birthdays, appear to have started their army lives in one of a number of induction units before being brought together for basic training as 72nd Training Reserve Battalion (TRB) at the camp at Prees Heath in Staffordshire, in early August 1917. From that point on, their movements were identical until they disembarked in France in April 1918 (see Figure 13), and it is clear that they trained together as a single unit.

Figure 13: My father's route through training, from enlistment in July 1917, to arrival in France April 1918

In October 1917 the army revised its training structure and the 72nd TRB became the 53rd (Young Soldier) Battalion of the Kings Liverpool Regt. So, on 1st November the whole contingent of 131 packed their kit bags and set off from Prees Heath to Kinmel Park Camp near Rhyl in North Wales. Once there, they were issued with new Kings Regt. insignia and allocated new service numbers in the 95*** & 96*** series that appear on, or could be deduced from, the Medal Index cards. A few days later, on 9th November, most (probably all) of them were sent home on six days leave and I believe this is when my Dad's photo in his new uniform (Figure 1) was taken in New Brighton.

At the end of November 1917, they passed out from basic training and set off once again, this time to Fermoy, 20 miles north of Cork in Ireland, where they became 'D' Company, 51st (Graduated) Battalion Kings Liverpool Regt.[x] Three months of more advanced training in Ireland followed, then in March 1918 they were shipped to Great Yarmouth. They'd been there only a matter of days when alarms rang in every military establishment in the country.

When Russia had withdrawn from the war after the October Revolution of 1917, a million seasoned German troops from the Eastern front were released for deployment in France, and on 21st March 1918 they launched a massive assault against the British lines on the Somme, aiming to take Britain out of the war and forcing France to surrender. The defences couldn't hold, and every man was needed urgently at the front to absorb the momentum of the attack.

When the Kings Liverpool boys had signed up, the call-up age was eighteen years with an undertaking that no one would be sent on active service until they reached the age of nineteen. That implied a training period of about 12 months. However, in response to the critical situation on the Western front in March 1918, that undertaking was revised and the authorities decreed that all young men who had reached the age of 18 years 8 months could be sent on active service.

They had just achieved that qualifying age, so their training was abandoned about four months earlier than planned - their time had come. They were hastily reassigned from their training battalion to the 4th Battalion Kings Liverpool Regt. before boarding a train for the Kent coast and embarking for France on 4th April 1918.

"Lifebelts were issued as we went up the gangways, and soon the old boat, a cross-channel steamer, was full of men; decks, stairs, passages, all crowded with soldiers in full equipment. During the crossing we were accompanied by a Royal Navy cruiser and two or three destroyers which circled us; while overhead several aeroplanes flew to and fro to spot any German U-boats. The excitement among the boys was intense."

The words are those of Frederick Hodges from his book "Men of 18 in 1918" in which he recounted his WW1 experience with the Lancashire Fusiliers.[xi] Hodges was an almost exact contemporary of my father, just 18 days younger, and he followed precisely the same training regime (though with the Bedfordshire Regt. rather than the Kings Liverpool). He crossed the Channel on 5th of April 1918, the day after my Dad and, though neither of them ever knew it, their paths were to cross a week later.

France and a change of Regiment

My father disembarked in France on 5th April as a soldier of the 4th Battalion Kings Liverpool Regt along with the 130 other young lads with whom he had trained for almost nine months. I had already discovered that 100 of them were selected for transfer to the 7th Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment and the service records confirmed that the transfer took place at Infantry Base Depot G in Étaples on 7th April 1918.

Frederick Hodges had disembarked in Calais the previous day, and his account recalls:-

"When we reached Calais, after several hours we disembarked and marched to a base camp where we were lined up in a very long single row. We were then counted off into groups destined for different battalions. Friends who stood in line next to one another were parted by a hand and an order, then marched off to different Regimental Base Headquarters. These were bell tents in a long line, where particulars were taken, and to our surprise, new regimental numbers were given to us. My number was changed from 44243 to 57043. In this peremptory way, I and about 300 others suddenly became Lancashire Fusiliers, while some of our friends became Manchesters or Duke of Wellingtons or East Yorkshires."

My father's entry to France and to the base depot at Étaples, was probably via Boulogne, but his experience must have been very similar - though with one significant difference. Whilst both young men were probably lined up in a long row as Hodges described, my Dad's contingent in Étaples was marshalled in alphabetical or numerical order – Hodges' group in Calais were not. Perhaps the alphabetical/numerical ordering system that I described earlier applied only to troops arriving in Étaples, but it is that single, simple, and perhaps rare, factor that has made this whole investigation possible - and so successful.

Consulting War Diaries

Every unit on active service in the World War 1 army was required to write a daily "War Diary" from the moment it landed abroad, and these documents contain the most interesting information. Once you know the number of the battalion or the battery that your man belonged to, its diary will tell you, day-to-day, where his unit was, what it was doing, and what was going on around it.

A selection of war diaries has been available from TNA Documents Online since about 2008 and I was lucky, the war diary of my father's battalion was included. The National Archives are currently digitising the remainder and it is hoped that the project will be completed, and that all diaries will be available online, by the end of 2018.

I began my study of the 7th Norfolk's diary at 7th April 1918, the day my father was assigned to his new regiment and his number was changed from 96003 to 49085.

To the Front

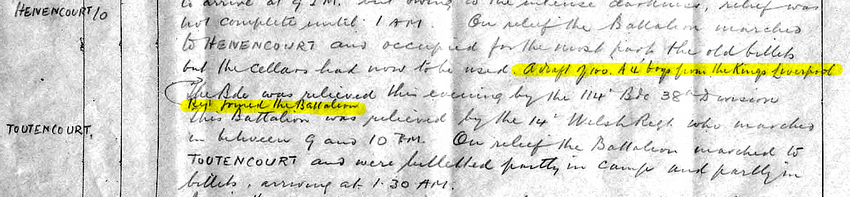

The 7th Bn of the Norfolk Regt. had been holding the line in the vicinity of Albert in the Somme region for some weeks when the weight of the German offensive fell upon them on 21st March, and their losses were heavy. In the ten remaining days of that month 11 officers and men were reported killed, 80 wounded and 212 missing. On 10th April the survivors were withdrawn from the front to a rest area at Toutencourt some 8 miles behind the lines and en-route they paused briefly in the village of Hénencourt (see map Figure 21)

The war diary was fascinating reading, not least because there, on the page for 10th April (Figure 14), was a note squeezed into the white-space between paragraphs which read:-

"A draft of 100. All boys from the Kings Liverpool Regt. joined the Battalion”.

Figure 14: The 7th Norfolk diary entry for April 10th written at Hénencourt, and amended later that evening.

It was a most unexpected, but superb find. If all the preparatory work had not been done it would have meant nothing, and I would have passed straight over it. As it was, it jumped from the page and graphically confirmed the results of the whole investigation thus far.

The note was clearly an afterthought, inserted after the diary entry for the day had been written. So, the 'Liverpool boys' must have arrived at Hénencourt, about three miles west of Albert, in the late evening of 10th April at about the time that the depleted 7th Bn. resumed their march from the front to billets in Toutencourt.

No other draft recorded in that year numbered 100, and no other diary entry referring to replacements mentioned the source regiment. It seems to indicate that the combination of them being described as 'boys' and all from the same regiment was unusual - which further implies that they must have been among the first of the under 19-year-olds to reach the front.

My Dad once said that they were sometimes greeted with a bleating "Baa,aa,aa..." sound from seasoned troops, meaning "Here come more lambs to the slaughter", as they passed by with their fresh faces, unsoiled uniforms, and obviously new equipment. Such sights and sounds were to become commonplace as the days went by however - it has been estimated that half the British Army in the latter half of 1918 was made up of young lads of 19 years or less.

Figure 15/15a: Present day views of Hénencourt. The chateau is just visible at the top of the main street. It was an odd feeling to walk in my father’s footsteps from almost 100 years before

Paths Cross

My Dad and Frederick Hodges followed very similar routes to the Somme front in the sector just north of Albert. Indeed, their paths actually crossed on April 11th or 12th when the 7th Norfolk's war diary records that my father's battalion used the bathhouse at Toutencourt. At that same time, Hodges' new battalion, the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers, used the same facility - and he left us a descriptive account.

"It was while we were in Toutencourt from 11th to 14th of April, that we had our first experience of an army bathhouse.

We were marched some miles to the bathhouse and sat down in a field to wait our turn with other troops of various battalions. These bathhouses were rough sheds with corrugated iron roofs, and were divided into several compartments. Outside was the little boiler house which heated the water. We queued up to enter, and in the first compartment we rapidly undressed, throwing our underclothes into large wooden crates. We bundled our tunics, trousers, puttees and boots and handed them through a trapdoor into another compartment. Naked, we passed into the bath section, which had a concrete floor with a drain in the centre and overhead a number of one inch diameter pipes with small holes drilled in them.

The corporal in charge of the bathhouse gave the order to the man outside at the tap of the boiler "Turn 'er on, Bill!" A thin trickle of lukewarm water began to splatter down onto us from above as we stood in close proximity, twenty or thirty at a time, endeavouring to create a lather with our small pieces of army soap. By the time we had succeeded in washing about half of our bodies, we heard the order "Turn 'er orf, Bill!".....

… Protesting loudly, we passed into the next section, where we were given a towel and a set of underclothes...... My own change of underclothes was of a reasonable size, but of a quality very much poorer than those I had discarded. When I tried to put my trousers on, I found that they did not fit, and in the pockets I found someone else's possessions ..... Eventually, I found the man who had been given my trousers and tunic and so got them back."

Although the two young men were stationed for the next three months in the same general area, mostly around Forceville, there is no evidence that their paths crossed again.

My father reached the front line for the first time close to the village of Mailly-Maillet on 24th April, a fortnight after joining his new battalion.

A baptism of fire

Like most of the men who took part in WW1, my father was reluctant to talk about it, but when I was a young lad, maybe around 13 years old, he took me to see the film "All Quiet on the Western Front". It was unusual, "going to the pictures" was normally a family outing at that time but this was different - the only time my Dad and I went on our own and it made a big impression on me, as I guess he intended. Even now, over 60 years later, I still remember where we sat in Wallasey’s "Capitol" cinema and images from the film are burned into my memory, especially the final butterfly scene.

On the walk home in the damp, gas-lit winter dark he said simply "It was just like that", and after a pause he recounted an incident from his own war. In retrospect, I now realise he was telling me how, at the age of 18, he was suddenly made acutely aware of how thin the margin between life and death had become.

He told me that he'd been sent forward one night, with an experienced "old sweat", to do a spell in a listening post at the end of a sap leading out from the front line some distance into no man's land (the purpose would have been to listen for any activity in the enemy line, digging new trenches or installing new wire entanglements etc). Nothing happened. So, when their stint was over, they reported back to the duty officer and Dad returned to his section's trench position - to find it empty and that all his mates had disappeared. He was told that a shell had exploded in their midst and they had all been taken down the line to the dressing station.

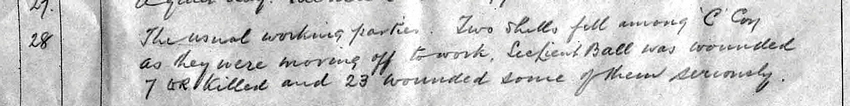

I think, though I can't prove it, that the incident he described to me that evening is the one recorded in the battalion diary for April 28th 1918 four days after he stepped into the front line for the first time. If I'm correct, it's likely that my Dad was in "C" Company. The diary entry (Figure 16) reads:

"The usual working parties. Two shells fell among 'C' Coy as they were moving off to work. Sec Lieut Ball was wounded. 7 OR killed and 23 wounded some of them seriously."

Figure 16: 7th Norfolk war diary for April 28th 1918 (OR = Other Ranks)

Figure 16: 7th Norfolk war diary for April 28th 1918 (OR = Other Ranks)

When my Dad referred to his 'mates' he must have meant the lads he'd trained with - and of the 30 casualties that night eight were 'Liverpool boys'.

Commonwealth War Graves records confirm that one of them, 49070 Jim Littler from Northwich, was one of those killed, and at least seven were among the wounded[xii]

49025 Robert Foley

49068 Austin Lewis

49071 Geo. S. Lundy

49079 Ernest Potts

49082 Arthur Radfirth

49087 James Rowlands

49098 Harry J Whipp

It was my father's first narrow escape !

Defending the Front Line

After 3½ years of war, a spell (or "tour") in the trenches had come to mean about four days in reserve, four days in the support line and four days in the front line, followed by a return to a rest area a few miles back - though the terms "reserve" and "rest" are not to be taken too literally, almost every night was spent in working parties carrying supplies of all kinds up to the front line or repairing damaged trenches, roads, or barbed wire.

But at this time, in the turmoil of the German Spring Offensive, the pressure on manpower was such that a tour at the front seems to have become six days or more at each location in the trenches. It was a very tough introduction to the war for the raw 'Liverpool boys' and the other young lads like them.

Between April and May 1918 the 7th Norfolks undertook three such tours in the line near Mailly-Maillet, interspersed with rest periods around Lealvillers and Acheux (See map Figure 21). During this period the battalion received at least 180 raw replacements (including the 100 Liverpool boys) so in June they were withdrawn to Arquèves, about 9 miles behind the front line, for three weeks battle and survival training - including field tactics, musketry, use of rifle grenades and gas drills - before returning to the front in the last week of June.

My Dad celebrated his 19th birthday in a frontline trench in Aveluy Wood, just north of Albert, relatively undisturbed. The war diary for 30th June 1918 reads :-

" Very quiet day. Rations and water arrive at 8 pm as an attack commences at 9:30 pm on our right. We provide no working parties during the night".

(The attack mentioned was carried out by the 6th W.Kent & 6th Queen's Bns).

A week later, on 9th July, the 7th Norfolks were withdrawn again for further training, this time in St Sauflieu, south of Amiens. There they prepared for the Battle of Amiens which would begin the last phase of the war - the last 100 days that would finally push the German army out of France. The attack was scheduled to begin in the early morning of 8th August

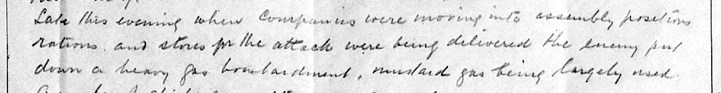

After their three weeks intensive battle training they moved to Treux about 3½ miles SW of Albert on 30th July, then into the support line in CLARE RESERVE trench (See map - Figure 18) before moving forward to assemble in the front-line system seven days later.

On 7th August the Battalion received their orders to go over the top at 06:20 the following morning to occupy the village of Morlancourt, and the war diary goes on to say:-

"Late this evening, when Companies were moving into assembly positions [and] rations and stores for the attack were being delivered the enemy put down a heavy gas bombardment, mustard gas being largely used".

Figure 17: 7th Norfolk War Diary extract from the 7th August entry

Among the victims of this gas attack were Brigadier General Berkeley Vincent,[xiii] commander of 35th Brigade (of which the 7th Norfolks were a part) and, as I now know, 49085 Private T. Robinson, my father.

Figure 18: My father was gassed whilst his battalion was assembling to attack the village of Morlancourt on the opening day of the Battle of Amiens, 8th August 1918. (Trench map from the McMaster University series)

Casualty Records of wounded soldiers

Casualty details of those who died in the war have been recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and their database is available freely online - but details about wounded soldiers are not so easy to obtain when the service record is missing.

The primary public source of all casualty information in WW1 was the Daily Casualty List compiled by the War Office from medical reports and distributed to national and local newspapers. The full lists were published by The Times, The Scotsman, and The Irish Times, whilst local newspapers would generally extract and publish names and regiments relevant to their own areas.[xiv]However, there are significant gaps in the record in late 1917 and throughout 1918 for two main reasons. Firstly, not all the data has yet been digitised, but primarily because the War Office ordered the publication of casualty lists in newspapers to be curtailed in August 1917 in response to a severe shortage of paper.

The reason being that after three years of war, German submarine activity had reduced timber imports to the UK to such an extent that the availability of wood pulp, which was required not only for making paper but also for manufacture of explosives, had declined to a critical level and the War Office deemed it necessary to reduce the size of newspapers. After August 1917 those newspapers unable to quote official sources appear to have relied largely on casualty information provided by their readers and thus later casualty lists in the local press are far from comprehensive.

Over a lengthy period, I had examined all of the relevant on-line newspaper sources in the attempt to pinpoint the date when my father was gassed, and his local newspaper archive had been searched twice (once with the much appreciated help of the Wallasey branch of the Family History Society of Cheshire) without success. Eventually I resigned myself to the conclusion that I would never find that last piece of information.

Then suddenly, after a number of years, during which more information had come onto the web, by sheer chance, I stumbled across a clue that caused the knot to unravel (described in "The End of my Dad's War - An Unexpected Conclusion", below) - it spurred me to revive the search for the gassing incident.

My Dad's casualty record

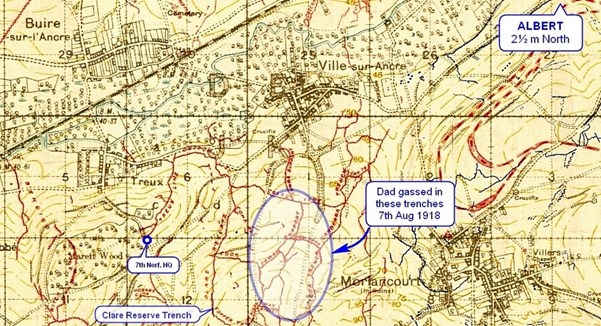

The renewed search led me to the Norfolk Regiment Museum via a posting on the Great War Forum[xv] that referred to a "Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book" (NRCB).[xvi] It implied that, uniquely among British military establishments, the Norfolk Regiment had kept a record of its casualties throughout the war - and indeed this proved to be the case.

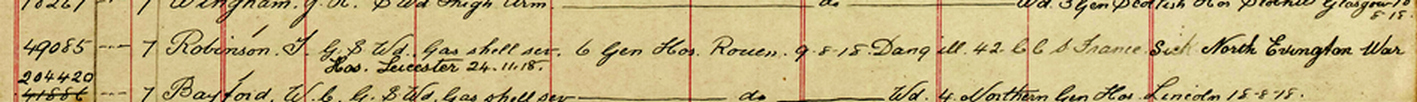

Figure 19: My father's entry in the Norfolk Regt. Casualty Book

The book, over 100 years old and well worn in that time, seems to have been compiled from medical records relating to soldiers serving with the Norfolk 1st & 2nd (Regular) and 7th, 8th & 9th (Service) Battalions. It contains over 15,000 entries on 400 pages which, during the process of rebinding, were photographed for conversion into a searchable database. Images are not yet transcribed digitally (2017) but an individual record image can be found manually via an alphabetic name index - my Dad was on page 189b.

His entry in the casualty book shows that he was admitted to the 6th General Hospital at Rouen on 9th August 1918 having suffered a gunshot wound (GSWd)[xvii] and gas poisoning.

I'd always known that my Dad had been gassed in the war. I don't recall anyone ever telling me that, it seems to have been one of those bits of instinctive knowledge you just absorb unconsciously as you grow up, but to find that he suffered a bullet or shrapnel wound is a surprise - it was never mentioned at home. It would seem that the wound may have been so slight that he made a complete recovery and deemed it unworthy of comment in later life … but it was his second narrow escape - by inches.

Gassed

It seems that he passed though the casualty treatment chain - Regimental Aid Post, Field Hospital, Casualty Clearing Station to Base Hospital near the Channel coast - in two days, and at an early stage his incapacity would have been assessed as Slight, Mild or Severe. His condition on admittance to the hospital in Rouen was described as "Severe".[xviii]

Despite the awful physical and psychological effects of gas, the fatality rate was relatively low compared to bullet or shrapnel wounds - about 97% of gas casualties recovered, though some of them would suffer a prolonged degree of incapacity, and for many more there would be repercussions in later life.

By autumn 1918, 70% of men exposed to gas were returned to duty within eight weeks.[xix]

My father certainly returned to his battalion at the front, but there are no clues as to the date. The average six weeks recovery time would suggest around 20th September, so he may have taken part in the action against the strongly fortified village of Epéhy (18th/19th Sep). There is no evidence that he did, but he was certainly back in active service when his battalion moved north at the end of September.

The photograph (Figure 20) came to light following a death in the family in 2016 and I had not seen it before. The printed heading on the back reads "CARTE POSTALE" proving that it was taken in France - most probably in Rouen during his recovery from the mustard gas attack.

Surviving the gas attack was his third narrow escape.

Figure 20: Photo taken in France most likely in Sept. 1918 during his recovery in Rouen.

The last 100 days

Whilst my father was recovering from gas poisoning his battalion was heavily involved in the advance that would lead eventually to victory.

At 6:20 am on 8th August, the 7th Norfolks had clambered out of their trenches and in a few hours had established a new front line between Morlancourt and the River Ancre to secure the northern flank of the advance by Fourth Army. Records indicate that in the assault four of the 'Liverpool boys' died and at least 8 were wounded.[xx]

Those killed were :-

49018 James Dorian, 49024 Andrew Ferguson, 49043 Thomas Hinchcliffe,

49046 John Holland.

Those wounded included:-

49000 Frank Colman, 49014 William Deans, 49059 Reginald Jones,

49060 Henry Kearns, 49067 James Leigh, 49077 Francis Millington,

49078 Michael Mooney, 49064 Harry Kirkham.

In two days they drove forward two miles, and the war diary records that the advance continued throughout the month with strong enemy positions being overcome at Meault and Mametz. The end of August saw the battalion at Maurepas having covered a distance of about 10 miles in 23 days.

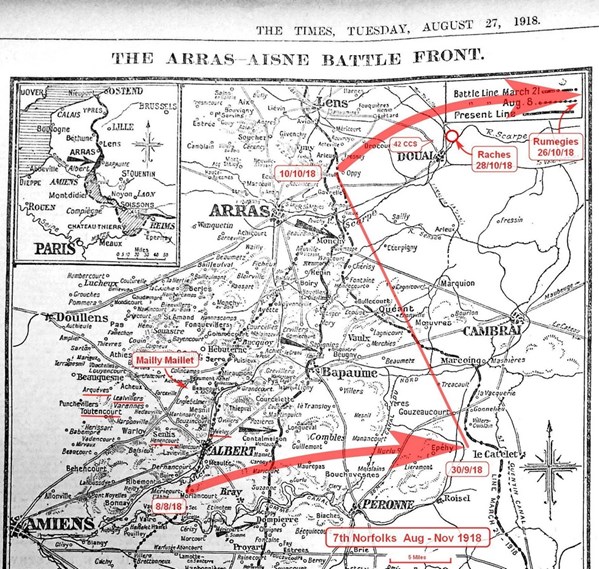

Figure 21: 7th Norfolk's advance 8th Aug. - 28th Oct.1918 overlaid (in red) onto a map published in The Times on 27th Aug 1918. Locations from April to July referred to in the text are underlined in red.

Figure 21: 7th Norfolk's advance 8th Aug. - 28th Oct.1918 overlaid (in red) onto a map published in The Times on 27th Aug 1918. Locations from April to July referred to in the text are underlined in red.

Pursuit of the German forces gained momentum during September and major actions took place at Nurlu on the 7th and at Epehy on the 18th. By 30th September the battalion had reached the most easterly point of its advance three miles east of Epehy.

Overall, the two-month 25 mile advance from Morlancourt to Epehy had cost the battalion 37 officers and 634 other ranks, about two thirds of its official peacetime strength. The 'Liverpool boys' had lost another six killed and at least 13 wounded.[xxi]

Their Division, the 12th, which had led the two-month advance, had lost over 40% of its establishment in bringing Gen. Rawlinson's Fourth Army face to face with the formidable Hindenburg Line.

They were exhausted, and the history of the Division[xxii] records that

"During the night [of 30th Sept] the Division was relieved. It had …become so reduced in numbers as to be unfit for active operations until reinforced …. therefore it was withdrawn from the battle front."

The 12th (Eastern) Division was relieved by the 27th American Division and the next day they left the Somme front and began the 25 mile journey north towards Arras to occupy a trench line between Lens and Oppy, and I think it likely that it was at this point, whilst they were regrouping for the final advance, that my Dad re-joined the Battalion.

After a few days rest they began to move forward on 9th Oct when patrols found the German position in front of them unoccupied. The static lines of trenches were by now long behind them and their advance took them more and more into open country and through civilian occupied villages. The German forces were retreating steadily, though taking every opportunity to delay the Allies' progress by destroying anything that might be of use to their pursuers and laying booby traps.

The 7th Norfolks were once again the advance guard of 35th Brigade, covering 7 miles in 7 days to Courcelles where they were heavily shelled and lost 25 casualties including two more of the 'Liverpool boys' killed[xxiii] - 49076 Harold Miller and 49023 Hanson Farrar (C company) - who had been awarded the Military Medal twice. Finally they arrived at Rumegies on 26th Oct, having covered 23 miles in two weeks. At that point the 7th Norfolks had become so depleted that their active service came to an end; they were withdrawn to billets in Raches, 3 miles north east of Douai, and took no further part in the war.

The end of my Dad's war - an unexpected conclusion

When my mother told me that Dad was in hospital when the armistice was signed - she was right, but it was not for the reason I had assumed - it wasn't because of gas poisoning, it was because he was a victim of the Spanish flu epidemic that spread through the army and across the world in 1918.[xxiv] Discovering that fact was a breakthrough that came to light in an extraordinary way.

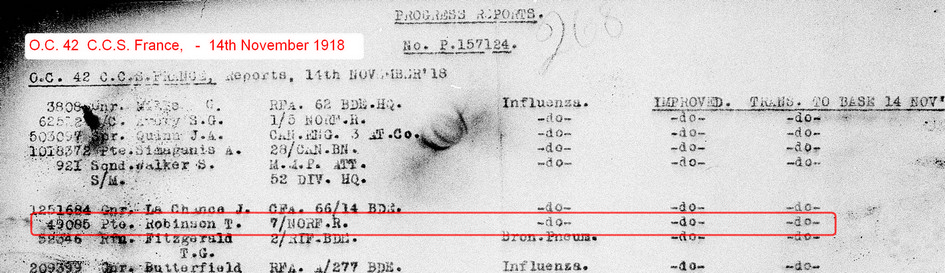

I'd long since given up looking for casualty records but browsing the web one day in 2016, I noticed that FindMyPast were offering a free weekend for military records. It was a site I hadn't used for some time. So, having nothing to lose and expecting nothing in return, I entered the briefest possible details into a service record search - simply an initial, a surname, and a number, "T > Robinson > 49085"[xxv] - and was astonished when a positive hit came up. It was a service record, not that of my father, but the record of another man entirely, Arthur Peacock of the West Yorks Regiment ! It was a file of 27 pages, one of which was a daily report of the 42nd Casualty Clearing Station listing 22 names - and incredibly, my father's name was one of those on that list (Figure 22).

Figure 22: Extract from the 42nd CCS report of 14 Nov. 1918. It names 22 casualties of which influenza claimed five dead and 14 sick - one of whom was my father.

It was pure luck! It could never have been found by logical deduction, and would not have responded to a name search if the list had not been transcribed into digital format.[xxvi]It was this clue that prompted me to renew the search to find out when he had been gassed, which led in turn to the Norfolk Regt Casualty Book (see "My Dad's Casualty Record." above).

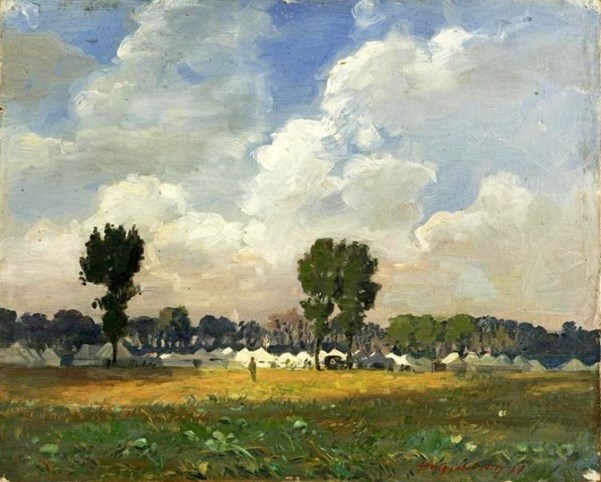

At the end of the war the 42nd CCS was a tented hospital located in the northern outskirts of Douai beside the road to Lens (see Figure 23). At that time their main activity was treating influenza cases - in the month of November 1918 they took in 1144 cases of which 60 proved fatal (5.2%).

Figure 23: 42nd CCS at Douai 1919. Oil on Canvas by John H Lobley. (I.W.M. Collection, Ref ART3765)

Figure 23: 42nd CCS at Douai 1919. Oil on Canvas by John H Lobley. (I.W.M. Collection, Ref ART3765)

My father must have developed flu symptoms whilst billeted in Raches, five miles north of Douai, before 5th November, the date that his battalion was moved east to Landas. On admission to 42nd CCS he was assessed as "Dangerously ill".[xxvii]

Some ten days later, in the report of 14th Nov. (see Figure 22 above) his condition was "Improved" and he was "Transferred to Base" (hospital) in Ambulance Train No. 26.[xxviii]

Cheating the Spanish Flu was his fourth narrow escape.

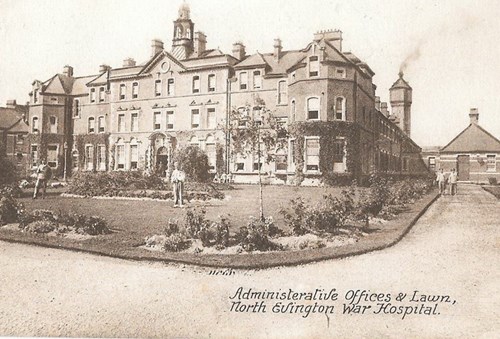

Nine days in Base Hospital near the French coast culminated in transfer to England where he was admitted to the North Evington War Hospital, Leicester on 24th November 1918.

Figure 24: Extract from the Norfolk Regt. Casualty Book showing my Dad's transfer to hospital in Leicester.

North Evington War Hospital, (now Leicester General) had 1010 beds in 1918. In 1919 it was ordered to close down, and by 29th May all patients had been discharged or transferred to other hospitals.[xxix]

Figure 25 / 25a: North Evington War Hospital, Leicester. (Evington Echo)

When he was admitted to the hospital in November 1918 my father's diagnosis[xxx] was given as "Bronchitis Pneumonia" as a result of having contracted Spanish flu with lungs that had been weakened by mustard gas just three months previously - conditions not easy to treat 100 years ago, clearly requiring prolonged hospitalisation at that time.

Figure 26: WFA Pension Record Ledger 3/MR/4933 giving 'Bronchitis Pneumonia' which was '20% due to his war service'. Source: WFA Pension Ledgers

His pension record card (see Figure 10) indicates a change of circumstance on 10 March 1919 that triggered a pension of 5s/6d per week until 9th Sept 1919. That suggests that his army service was terminated on 9th March 1919 but that he remained in hospital or convalescence, with a reduced pension (reflecting that subsistence was provided) at an unknown location, until finally being discharged from medical care in September 1919.

Confirmation comes from the Identity Cert. (Figure 3), which locates him at home in Wallasey drawing the first instalment of a full pension of 8s/0d per wk at his local Post Office on Poulton Road, Wallasey on 10th Sept 1919 and every subsequent week until 8th Sept 1920.

At that point his war was finally over. In just 214 days in France one in every four of his mates had been killed, and at least 57 had been wounded.

He himself had been wounded and had survived four near misses - he’d been lucky.

Appendix 1

What happened to the other 'Liverpool boys'?

The war diary provides no relevant information because names of ‘other ranks' are almost never given and, although the Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book (NRCB) is a unique source of information that has enabled me to put much of my father's experience of World War I into context, sadly the book itself is incomplete. Its last entries are from the first week in September 1918 - details from the last two months of the war are missing.[xxxi]

It is however possible to make a crude estimate of the unrecorded casualties by using the Commonwealth War Graves Commission details of those who lost their lives.

The 100 'Liverpool boys' suffered extremely heavy losses. CWGC shows that 23 died in total (almost one in four) during just 214 days in France with the 7th Norfolks - 17 were killed in their first five months of active service between Apr 10th and Sept 8th 1918 and 6 in the last two months, Sept 9th to Nov 11th. In the Apr/Sept period the Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book lists 45 of them wounded [xxxii] (ratio killed/wounded = 2.65) and 12 sick (ratio killed/sick = 0.70). Applying these ratios to the 9 week Sept/Nov period gives the results shown in the table below.

|

|

Between mid Apr & Sept |

Ratio Killed to Wounded or Sick (Apr-Sep) |

After mid Sept. |

Total Apr-Nov |

|

Killed (CWGC data) |

17 |

|

6 |

23 |

|

Wounded (NRCB data) |

45 |

2.65 |

16* |

61 |

|

Sick (NRCB data) |

12 |

0.70 |

8* |

20 |

|

Total |

74 |

|

30 |

104 |

|

* - Estimated figures (Killed x 2.65 Ratio and Sick x 0.70 Ratio) Those who were recorded wounded or sick twice or more were counted only once. |

||||

The fact that the estimate of total casualties is more than 100 reflects the broad assumptions in the calculation, quite probably a few survived unscathed - but it seems clear that almost all of the ‘Liverpool Boys’ would have made a personal sacrifice.

It lends credence to Michael Stedman's comment in his book "Advance to Victory 1918” referring to the last three months of the war as - "a savage period of conflict during which casualties, amongst British infantry units, rose to some of the highest levels recorded during the war."

A more accurate assessment of casualties may be possible by examination of The Pension Record Ledgers which are currently being digitised and close attention is being paid to each new tranche of data as it is released.

Appendix 2

Finding Private Marshall.

When I had completed the first part of this project - the analysis of service numbers - I posted a brief summary on the Great War Forum website which included the names of all 131 of the "Liverpool Boys". I received a number of positive responses over the next fortnight, which was encouraging, then everything went quiet and my personal circumstances kept me from the forum for a considerable time.

Then suddenly, quite unexpectedly nearly 3 years later, I discovered a message on the website that left me stunned. It said:-

"..... I was very interested to read your piece on the Great War Forum website. My father, 49073 Herbert W Marshall, was another of the 100 transferred from the Kings Liverpool to the Norfolk Regiment...."

The message came from Keith Marshall in Clitheroe Lancs. who was also researching his father's WW1 experience.

When over 5 million men from the UK served in WW1 the chances of coming across someone else, after almost 100 years, whose father trained and served in the same unit of 100 as mine, must be vanishingly small.

Keith told me that although his family lived in Clitheroe, his mother came from Staffordshire, and on visits to her family when he was a boy, they would drive past Prees Heath camp, at which point his father would talk about his army experiences. The family also spent a number of holidays in Conway, North Wales, which meant driving past Kinmel Park camp near Rhyl and these journeys too triggered memories. It seems his father Herbert was a close friend of 49023 Hanson Farrar who died at Courcelles on 18th Oct. 1918 and for many years he kept in touch with Farrar's parents, George & Mary.

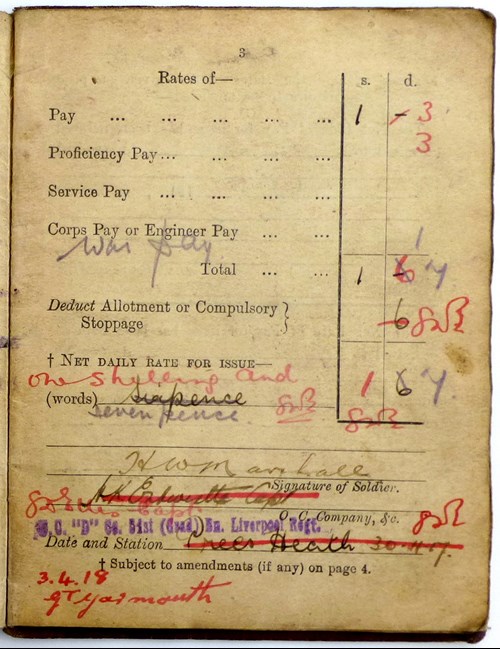

Herbert saved a number of pieces of memorabilia and documentation among which were his medals and pay book

Although our father's service histories would have been virtually identical, their medal inscriptions were different.

Figure 27: Herbert's British War Medal

Herbert Marshall's were stamped "L' POOL. R." with his Liverpool Regt no. "95990" while Robbie Robinson's were marked "NORF. R." with his Norfolk Regt no. "49085".

Herbert's were correct, a man's medals were supposed to be inscribed with his regimental details as they were on the day he landed overseas. My father's records seem to have been subject to administrative difficulties during the German spring offensive.would have been virtually identical, their medal inscriptions were different. Herbert Marshall's were stamped "L' POOL. R." with his Liverpool Regt no. "95990" while Robbie Robinson's were marked "NORF. R." with his Norfolk Regt no. "49085".

Herbert's pay-book shows that his net pay rose from 1s/6d to 1s/7d per day when they disembarked in France, the extra 1d/day was designated "War Pay"! The pay-book also confirms his Liverpool and Norfolk Regiment service numbers and reveals that the group of 131 "Liverpool boys" who trained together in Ireland were designated D Company, 51st (Grad) Battalion, Kings Liverpool Regiment.

Figure 28: Herbert's Pay book.

Figure 29: Keith's father, Herbert William Marshall

One of the stories Keith recalled from his father's wartime tales reflects social attitudes of the time. One day Private Marshall had been sent back to the rear to guide a replacement officer up to the Battalion's position in the line, and at one point in the journey they had to negotiate a spot where the cover had been blown in so that the route was exposed to observation by the enemy. Herbert pointed out that it was necessary to lie on the ground and crawl, but the officer in smart new uniform, scathingly refused and strode ahead resolutely - he was promptly shot dead.

Herbert too suffered gas poisoning. It happened on 2nd November 1918, just nine days before the war's end, when the Battalion was billeted in Raches just north of Douai, but unfortunately the war diary pages for 1st and 2nd November are missing, as are entries for October and November in the Norfolk Regt Casualty Book, so no further details are available. He was treated in Queen Mary Hospital, Calderstone, Whaley and at the King's Lancashire Military Convalescent Hospital at Clifton Park Blackpool.

Both of our fathers joined their local home guard in WW2 and both men had the rank of 2nd Lieut. It seems to have been common practice to commission ex-WW1 soldiers, in recognition of their active service experience.

Figure 30: Jef Robinson (l) & Keith Marshall (r) July 2013

ENDNOTES

[i] Surviving service records are now available on-line from subscription sources including Ancestry.com and FindMyPast.co.uk

[ii] It is said that about a third of army service records survived but my searches have yielded far less than that.

[iii] TNA Documents Online website address: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/medal-index-cards-ww1.htm

[iv] Nowadays the TNA search facility offers the option to download results as a '.csv' file, which can be opened directly in Excel - this should be a much quicker alternative.

[v] Later in the investigation, when I had uncovered a number of service records, I found that every one of them fitted into the inferred name/number sequence exactly, which proved my deduction to be correct.

[vi] With the digitisation of the records now being underway, the 'manual search' process is no longer available.

[vii] There are a number of providers of service record digital images. Ancestry and Find My Past are probably the most common.

[viii] CWGC website search page = http//www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead.aspx

[ix] Since this paper was written the CWGC database has been updated to allow multi-dimensional searches. It now works in a similar fashion.

[x] Keith Marshall, direct communication. See 'Postscript' p36.

[xi] Frederick James Hodges, "Men of 18 in 1918", published by Stockwell 1988. Hodges died in 2002 aged 102, it was the year I began researching this story.

[xii] A service record from the unburned (Pension) series has survived for one of the casualties - 49068 Austin Lewis. It shows that he was wounded on 28th April, treated at 1st NZ Field Ambulance the same day, admitted to 9th Gen Hospital Rouen on 1st May, and dispatched to England on 3rd May. The Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book (NRCB) is less comprehensive and shows only that he was admitted to the General Hospital Nottingham on 4th May. The other six wounded were identified from the NRCB by having hospital admission dates similar to Austin Lewis. Three of the six suffered wounds serious enough to require evacuation to UK hospitals and Lewis himself was discharged from active service on 24th July and awarded the Silver War Badge.

[xiii] Brig. Gen. Vincent was reported as wounded in The Times, 24th Aug 1918. At the time, the paper recorded only officer casualties, ordinary soldiers who had been killed or wounded were not listed - perhaps because of a paper shortage at that time. My father's admission to 6th Gen Hospital, Rouen on 9 August 1918 was recorded in the Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book.

[xiv] The national newspaper lists, insofar as they have been digitised, can be accessed via subscription websites, principally "The Genealogist" & "The Times Digital Archive", and there is a growing list of titles in the British Newspaper Archive accessible on the FindmyPast website

[xv] The Great War Forum is a freely available resource having tens of thousands of members worldwide covering a wide spectrum of interests centred on WW1. Its purpose is to share knowledge.

[xvi] Available at the Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum - Website: https://norfolkinworldwar1.org/2014/10/01/the-norfolk-regiment-in-october-1914-the-casualty-book/

[xvii] The abbreviation GSW came to be used to describe not only bullet wounds but also penetrating wounds from shrapnel or shell fragments. It's possible that this wound was caused by a fragment of the exploding shell itself.

[xviii] Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book, p 189b, Norfolk Regiment Museum, Norwich.

[xix] Edgar Jones, "The British Experience of Gas…. in the First World War" , War in History 2014, Vol 21(3)

[xx] Reported in the Norfolk. Regiment Casualty Book

[xxi] The Norfolk Regt Casualty book ends on 9th Sept so undoubtedly there would have been more than 13 wounded during the month. The full list of names and known casualties is given in Appendix 3.

[xxii] The History of the 12th (Eastern) Division in the Great War, 1914 - 1918, Maj. Gen. Sir Arthur B. Scott, Naval & Military Press.

[xxiii] from CWGC records. The war diary records only one man killed in the whole month, CQMS Houlton on 25th Oct, which illustrates the difficulty of maintaining accurate records under active service conditions.

[xxiv] It has been estimated that the world-wide death toll of the flu pandemic was between 50 and 100 million.

[xxv] Later, tests showed that a search for anything other than simply Initial, Surname & Number fails to deliver a result.

[xxvi] The 42nd CCS page can only be accessed from FindMyPast military records. In Ancestry.com the Arthur Peacock record contains that page, but its content has not been transcribed and thus it does not respond to a search for names other than Arthur Peacock.

[xxvii] Norfolk Regt Casualty Book, p189b (Figure 24)

[xxviii] 42 CCS War Diary

[xxix] "The Fifth Northern Gen Hospital, Leicester", Col L.K.Harrison, Leicester University Library.

[xxx] WFA Pension Record Ledger 3/MR/4933

[xxxi] There may have been a second volume that has been lost.

[xxxii] Certainly an underestimate. Two men known to have been awarded the Silver War Badge during this period are missing from the NRCB so it's likely that other wounded casualties will also be unrecorded.

Article by Jef Robinson

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to many people who were involved in this project especially :-

Keith Marshall, whose father served with mine in C Coy 7th Norfolk’s, and Hazel for their friendship, hospitality and additional material that they generously provided.

Kate Thaxton and staff at the Royal Norfolk Regiment Museum for access to the Norfolk Regiment Casualty Book, which provided the last and most important piece of the jigsaw.

The Western Front Association for preserving the MoD’s archive of pension record cards which, when digitised will become an outstanding resource for researchers.

The members of the Wallasey branch of the Family History Society of Cheshire for searching local newspapers on my behalf and members of the, Great War Forum website who volunteered their time and expertise to answering numerous queries.