A Family at War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Family at War

One of the most persistent and annoying heresies about the past is that it was much simpler than the present. We, the people of now, live complex, challenging lives; they, the people of then, lived simple, uncomplicated lives. There is a word to describe this, but I do not wish to bring the WFA into disrepute by placing it in print. Perhaps I may be allowed to add (for those in the know) that it is a word frequently uttered by our former President, Peter Simkins, when confronted by nonsense.

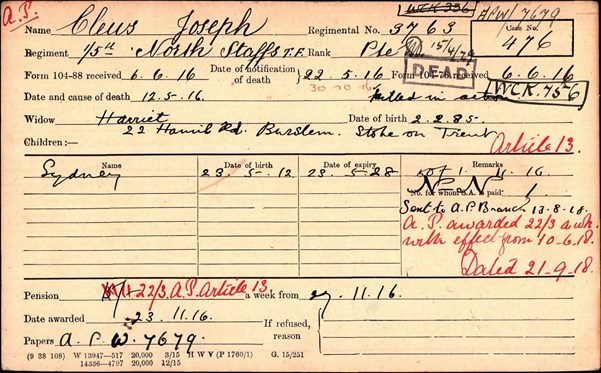

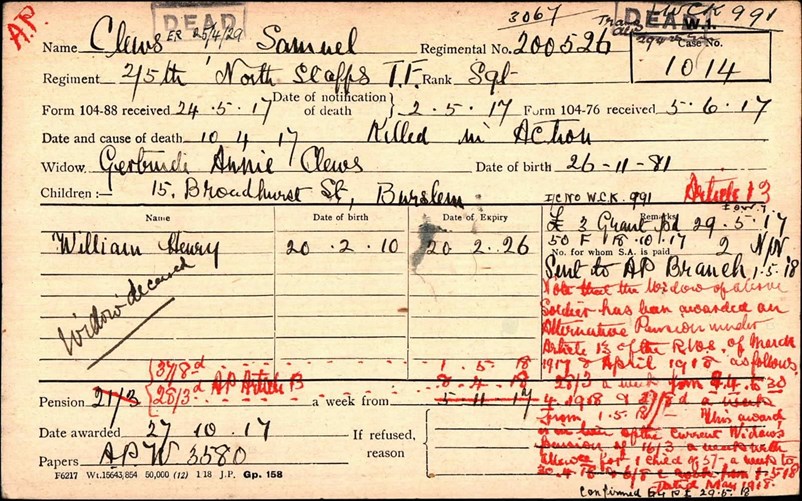

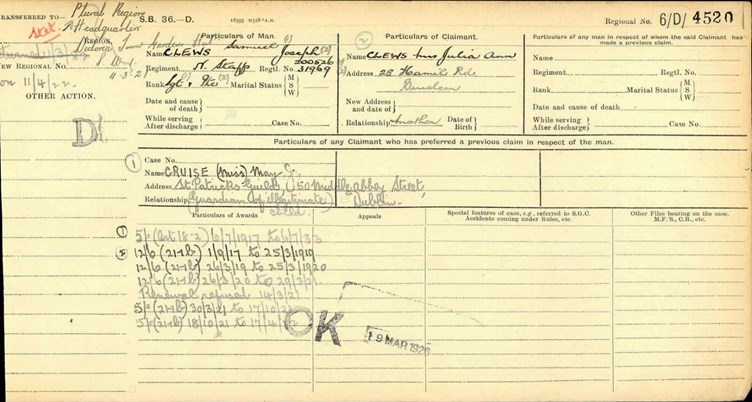

I was reminded of this heresy when my collaborator on the Burslem Roll of Honour, Mick Rowson, drew to my attention the history of one of Burslem’s war dead, Samuel Clews. This article started out as his story, but it became – quite rightly - the story of his wife and children.

When I was Director of the Centre for First World War Studies at the University of Birmingham I was often contacted by people who wanted to know in which ‘battle’ their ancestors had been killed. And just as often I had to explain that you did not need to be in a ‘battle’ to be killed in the First World War. This was the fate of Samuel Clews. Sergeant Clews was in the 2/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, 176th Brigade, 59th (2nd North Midland) Division TF. He was killed on 10 April 1917.

The division only arrived in France on 25 February 1917. It took part in no major engagements until the battle of the Menin Road Ridge on 23-25 September 1917, but from 17 March to 5 April 1917 it had been following up the retreat of the German Army to the Hindenburg Line (Siegfried Stellung). On 10 April 1917 the 2/5th North Staffords were in the line between Vendelles and Jeancourt, midway between Peronne and St Quentin. The battalion took part in ‘patrol activity throughout the day in touch with the enemy’. This is probably when Clews was killed. The only other man the battalion lost that day was the 18-years-old (or possibly 19-year-old) Private Thomas Wootton. They are both buried in Jeancourt Communal Cemetery Extension.(1)

Above: Jeancourt Communal Cemetery Extension

Samuel was the fifth of ten children of Henry Clews (1850-1908), a flat presser in the pottery industry, and his wife Julia (1850-1925).(2)

Their first born, Priscilla, died before her first birthday. Mary, Sarah Annand Harry were older than Samuel (b. 1881); Julia, Florence, Joseph, Ethel and Edwin (‘Edward’)were younger. All the sons served in the Great War. Joseph and Edward enlisted on the same day, 27 October 1914, and both joined the 1/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, 137th (Staffordshire) Brigade, 46th (North Midland) Division TF. Joseph arrived in France on 28 June 1915, Edward a day later. Joseph was killed on 12 May 1916 at Foncquevillers. (He wasn’t killed in a ‘battle’ either.)

He left a wife, Harriet, and a son, Sydney. Joseph Clews is buried in Foncquevillers Military Cemetery and commemorated, along with his brother Samuel, on the local Barnfields Memorial in Burslem (as ‘Clewes’).

Above: Foncquevillers Military Cemetery

Edward was discharged from the army on 31 October 1916 with a pensionable disability (rheumatism) and granted a Silver War Badge. (3)

His wife, Mary, died in 1928, aged 36, a few months after the birth of their tenth child. Edward died in 1965. He did not remarry.

The Great War was not the first in which Harry and Samuel had taken part. Harry was a Regular. He joined the army in November 1898 and served with the North Staffordshire Regiment until his final discharge, at the end of 21 years’ service, in November 1919, in the rank of Company Sergeant Major. Along the way he acquired the third and second class education certificates, passed the school of instruction for Mounted Infantry at Longmoor, obtained a qualification in chiropody and fought in the South African War. But it wasn’t all plain sailing. For a career soldier and senior NCO, he had a somewhat uneven record. In November 1910 he was reduced to the ranks (from Lance Sergeant) for ‘attempting to commit suicide’, and had two more ‘severe reprimands’ on his conduct sheet, one for ‘not complying with an order’, but worked his way back up the promotion ladder. When the war broke out he was a sergeant.

Although the 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment deployed to France in September 1914 Harry did not go with them. He was transferred to the 7th (Service) Battalion to bring it up to establishment, promoted to Colour Sergeant and appointed Company Sergeant Major on 19 August 1914. He landed with the battalion on the Gallipoli peninsula in July 1915 and later deployed to Mesopotamia as part of the only British division to serve there, the 13th (Western). In December 1918 he was stripped of his temporary rank of Regimental Sergeant Major, which he had held since December 1915, for ‘drunkenness’ by a Field General Court Martial and reduced in seniority in his permanent rank (CSM).He was awarded a pension on 1 December 1919, suffering from ‘nervous debility’ and ‘rheumatism’. He died in 1936, aged only 57.

Samuel also fought in South Africa. He volunteered for the Imperial Yeomanry on 9 March 1901, serving with 80th Company, 21st Battalion Imperial Yeomanry (2nd Sharpshooters).(4)

Above: A company of Imperial Yeomary in the Boer War (this image is of the 65th Company, 17th Battalion).

The decision to enlist looks selfish and callous. He left behind his 21-years-old wife, Gertrude (nee Kirkham), and five-months-old son, Samuel Charles (b. 15 September 1900). They had been married for just over a year. His wife was also three months’ pregnant with their second child, Gertrude, who was born on 26 September 1901. Samuel landed in South Africa on 15 March 1901. His son died six days later. The cause of death was ‘marasmus’, a catch-all term for malnourishment occasioned by nutrient deficiency, which sometimes resulted from poverty and scarcity of food, but could have other causes, including viral, bacterial and parasitic infections or underlying congenital weaknesses. A third child, Evelyn May, died from the same cause, aged fifteen months, on 26 January 1905. (5)

Samuel’s time in South Africa ended in the spring of 1902. He was invalided home in the hospital ship Simla on 19 April, suffering from ‘enteric [typhoid] fever’, a common affliction in the South African War.

Above: Hospital Ship Simla

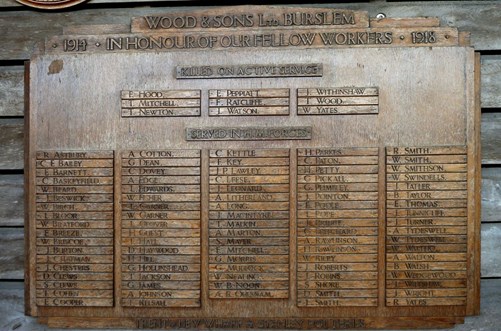

He was discharged at his own request on 2 July 1902 and returned to work variously as a carter, miner and potter. Latterly, he was employed by Wood & Sons Ltd as a ‘potter’s presser’ and is commemorated on their war memorial, now in the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, though curiously only as someone who served not as someone who was killed.

Above: Wood & Sons Ltd war memorial

He did no more soldiering until he again volunteered on 10 September 1914, joining the 2/5th North Staffords, a second-line Territorial unit, at that time-limited to Home Service. He was nearly 34 and had a wife and two children (their son William Henry was born on 20 February 1910). This time, Gertrude was not left entirely alone. Her parents separated in 1915 and her father, Thomas, came to live with her. Gertrude nursed him after he had a bad accident at work on 31 August 1915. While he was unemployed, he was unable to pay the 9s a week to his wife agreed under the maintenance order. Gertrude gave £10 from her own savings to her mother, who had no other means of support. Thomas Kirkham never really recovered from his injury. He died from sepsis in March 1917, a matter of days before Gertrude’s husband.(6) The war did not prevent Samuel fathering another child, which was born nearly three months after his death, but not to his wife.

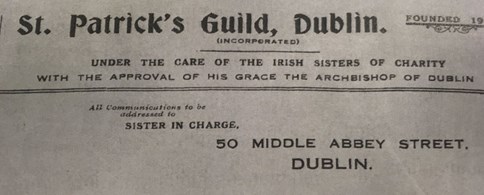

The 2/5th North Staffords, together with the rest of 59th Division, were deployed to Ireland in the wake of the Easter Rising of 1916. They remained there until the middle of February 1917. Samuel left behind a pregnant woman, Annie Ennis, who gave birth to a child on 6 July 1917. The child was placed in the St Patrick’s Guild in Dublin. This had been founded in 1910 by May J. Cruice, as a fostering agency for Catholic children.(7)

She made a pension claim on behalf of the infant, describing herself as ‘guardian of an illegitimate child’. We can only speculate on the nature of Samuel’s relationship with Annie Ennis. For Miss Cruice to make a claim on Samuel’s pension she would had to have shown compelling evidence that he was the father, which suggests that there was more to the relationship with Ennis than a ‘one night stand’. Their son, Patrick Joseph Clews, was born on 6 July 1917. On his birth certificate his mother’s name is shown as ‘Annie Clews, formerly Ennis’. The first twenty-one years of Patrick Joseph Clews’s life has left no available documentary record. We know that he was discharged from the British Army, Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment, on 19 December 1938, aged 21, and that he married a widow, Annie Wallace, at Chelsea Register Office on 18 January 1940. He stated his occupation as ‘hotel waiter’ and his father as ‘Samuel Clews (deceased), Sergeant 2nd Staffs Regt.’ [sic]. It is not known where Patrick grew up or whether his existence was known to the Clews family in Burslem.

It is to be hoped that Gertrude knew nothing of her husband’s illegitimate son. It is impossible not to feel for her. Samuel Clews abandoned her to go to war, not once but twice. She lost two children in infancy, witnessed the break-up of her parents’ marriage, and saw her father die a few days before she learned of the death of her husband. There was to be no happy ending for her. She did not survive the war either, dying – almost certainly unpleasantly - on 14 September 1918, aged 37, from pulmonary tuberculosis and ‘exhaustion’. She was a woman who deserved more of life. It is difficult to imagine the Clews family greeting the end of the war with much jubilation. Julia, the matriarch, had lost her husband, two sons and a daughter-in-law, two daughters-in-law had lost their husbands, two of her grand-children had lost both their parents and another had lost his father. It is sometimes difficult to escape the warm retrospective glow cast over the experience of British women in the two world wars by the smiling face of ‘Rosie the Riveter’. Some women may have enjoyed (often temporary) escape from drudgery and poverty through employment in war-related industries, though such industries were few and hazardous in North Staffordshire, but for most women, especially wives and mothers, the reality was years of fear, loss and pain and a constant struggle to keep their homes and families together in the face of unsympathetic bureaucracies and interfering charities, while the return of peace did little to allay the ever-present threat of economic catastrophe.(8)

It was Gertrude’s family, the Kirkhams, who came to the rescue. Gertrude’s brother, William, had emigrated to Canada in 1904 at the age of 29 and settled in Toronto. He travelled to Canada on the SS Lake Erie with three other Potteries men, John Colclough, George Tunstall and Fred Boyd. All were described as ‘packers’, which perhaps suggests they had been recruited by someone with a need for their skills. (9) William Kirkham seems to have been a man of ability and ambition. By the time of the Canadian Census of 1921 he was described as a ‘[commercial] traveller’ and at his death in 1940 was a ‘stock broker’. The 17-years-old Gertrude went to Canada to join her uncle in 1919, sailing from Liverpool to St John’s, New Brunswick, on the SS Scandinavian. She was described on the passenger list as ‘a shop assistant’. She married in 1927.

Above SS Scandinavian (Canadian Pacific Line steamship)

Gertrude Snr’s sister, Elizabeth Baddeley, became William’s guardian and she received Samuel’s ‘war gratuity’ in 1919. William joined his sister in Canada in 1925, aged 15, having emigrated on the maiden voyage of the SS Letitia. His passage was paid by the United Services Fund. (10)

Above: a holiday home belonging to the the United Services Fund

Young William’s proposed employment on arrival in Canada was as a ‘printer’. This was also the occupation of his soon-to-be brother-in-law, Samuel Painter. When William married in 1931, aged 21, he was described as a storekeeper (shop owner). Samuel Painter was one of the witnesses, which suggests that the Clews orphans had stayed together as a family, against all the odds. They had arrived in Canada as ‘not quite strangers’ and seemingly prospered in ‘a land of promise’. (11) If so, no one could begrudge them their good fortune.

Article by J.M. Bourne

John Bourne taught History at Birmingham University for thirty years before his retirement in September 2009. He founded the Centre for First World War Studies, of which he was Director from 2002 to 2009, as well as the MA in British First World War Studies. He has written widely on the British experience of the Great War on the war front and the home front. He is currently completing a multi-biography of Britain’s Western Front Generals. He is a Vice President of The Western Front Association, a Member of the British Commission for Military History, a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Hon. Professor of First World War Studies at the University of Wolverhampton.

[I should like to acknowledge the invaluable help of Michael Carragher, Su Handford, Dr Alison Hine, Andy Johnson, Dr Geoffrey Noon, Mick Rowson and Craig Suddick in the research and writing of this article.]

Notes

(1). The personal inscription on Wootton’s headstone reads ‘REMEMBRANCE IS A FLOWER THAT NEVER DIES WHEN WATERED BY TEARS OF LOVE. R.I.P.’

(2). Samuel’s mother is referred to as ‘Julia’ in most documents, except her birth registration, where she is ‘Juliet Ann Procter’, and her marriage certificate, in which she is (weirdly) registered as ‘Juliet Ann Richardson Procter Allen’. No trace of the names ‘Richardson’ or ‘Allen’ have been found in her family tree.

(3). The surviving documentation is contradictory about the date of Edward’s discharge. His Pension Ledger says 31 October 1916; other sources say 31 August 1917. He seems to have applied for a pension after discharge and this was awarded from 4 July 1917, which suggests the 1916 discharge date is correct. The Sentinel newspaper of 12 May 1917, in reporting brother Samuel’s death, also described Edward as having been discharged. He was awarded the Silver War Badge [No. 403976] on 20 April 1918.

(4). Samuel’s attestation form for the Imperial Yeomanry states that he had served three years in the ‘1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment’, but this would have been the 1st Volunteer Battalion, which had a company in Burslem. The Regular 1st Battalion was in India from 1897 to 1903.

(5). I confess that when I discovered a second child had died of malnourishment, I became suspicious, but it is doubtful whether the deaths of these children resulted from ‘bad parenting’. Samuel appears always to have been in work and Gertrude possibly was, too. She was employed as a ‘potter’s decorator’ at the time of the 1911 Census, despite having a one-year old child and another of school age. This suggests she had access to family child support. They were living in good accommodation on the then recently built (and still standing) Park Estate in Burslem and there was no one else living with them, either in 1901 or 1911. There is no evidence of ‘official suspicion’. There were no inquests. Infant mortality in England had declined steadily between 1865 and 1885, but rose again until 1900 after which it began an uninterrupted decline to the present day. Even so, the infant mortality rate in 1905 was 200.16 deaths per 1,000 live births. The deaths of Samuel Charles and Evelyn May would have been regarded as ‘normal’, despite increased state concern with the health of the young and the future of the nation and Empire. See Carol Dyhouse, ‘Working-Class Mothers and Infant Mortality in England, 1895-1914’, Journal of Social History, 12 (2) (Winter 1978), pp. 248-67.

(6). Thomas Kirkham’s employer, Arthur Cliff, carting contractor, eventually agreed to pay his widow, Alice (Gertrude’s mother), £100 in compensation.

(7). Her name is spelled ‘Cruise’ on the pension documents. St Patrick’s Guild was taken over by the Catholic Church in 1943. Its reputation is currently mired in scandal, see the Irish Times, 12 March 2021.

(8). Andrea Hetherington’s excellent British Widows of the First World War: The Forgotten Legion (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2018) is a salutary corrective to the view that women ‘did well out of the war’.

(9). William was described as a ‘potter’s packer’ in the 1901 Census. It was a skilled job and often highly paid.1900-13 were the peak years of British emigration to Canada, with 3.15M emigrants. The Canadian government pursued an aggressive immigration policy that favoured people willing to work in agriculture, seen as vital to the development of the Western provinces. Assisted passages were sometimes available, but even if they were not a steerage fare on an emigrant ship could be obtained for sums in the region of £5.

(10). This was established by the British government in 1919, under the chairmanship of the former GOC Third Army, Julian Byng. It was given responsibility for disbursing the profits made from overseas army and navy canteens, a sum that eventually amounted to £7M and became known as ‘Byng’s millions’. As these profits came out of the pockets of soldiers and sailors, it was felt right that they should be spent on the care and support of ex-servicemen and their dependants. Byng accepted the job on the understanding that the organization would be independent of government.

(11). ‘Strangers in a Land of Promise: English Emigration to Canada, 1900-1914’ was the title of a research project at the Edinburgh Centre for Global History.