A Farewell to the Army Service Corps: The story of 'another' Ernest on the Piave

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Farewell to the Army Service Corps: The story of 'another' Ernest on the Piave

Many of those with a passing interest in the First World War may be familiar with the semi-autobiographical account 'A Farewell to Arms' written by Ernest Hemingway which was first published in 1929. This tells the story of the activities of a soldier of the American Red Cross (in effect a thinly disguised Hemingway) on the Italian front in 1917-18.

Above: 'Farewell to Arms' by Ernest Hemingway: the semi-autobiographical account of his service in Italy

It will not be surprising that Hemingway wasn't the only 'Ernest' to have been in the area of the Piave river, and the following article is an account of another Ernest - from Bethnal Green rather than Chicago - who for 100 years was buried under an 'unknown' headstone. At last, in November 2018, Ernest Robert Jordan's family have been able to visit his final resting place.

First Visit

Back in the 1970's Harry and Irene Gould visited Giavera British Cemetery. The town is some 30 miles or so north of Venice.

Above: Giavera British Cemetery. (Image courtesy of Eggle Views / Google Maps, 2016)

This was not a random visit, it was very specific, as Irene was there to look for the name of her father, Driver Ernest Robert Jordan of the Army Service Corps. Driver Jordan (who was known by his middle name) was drowned in an accident at the end of October 1918. Robert's body was thought not to have been found and he was therefore commemorated on the Giavera Memorial which stands at the rear of the cemetery. This memorial lists the missing of the British campaign in Italy in the First World War. The memorial is small by the standards of other memorials to the missing - with about 150 men named who have no known grave.

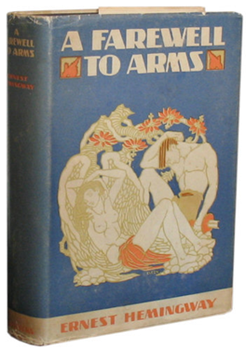

Above: Ernest Robert Jordan. Image courtesy of Carol and Gavin Adams

Above: The Giavera memorial. (Image courtesy of Giampietro Bonamigo / Google Maps 2016)

No doubt Harry and Irene found - towards the end of the memorial - the names of the men from the 'other corps' of the army. The Royal Army Service Corps being listed between the Labour Corps and the RAMC. Here they would have seen the name of Driver ER Jordan of the RASC.

Inevitably they would have wandered around the graves in the cemetery, which is on a sloping site not far from the Asiago plateau where the most important actions took place involving the British action in Italy during the war. The cemetery itself contains the graves of over 400 men who were killed mainly between December 1917 and the end of the war.

The visit to the memorial at Giavera was mentioned to other members of the family. Among these was Robert's elder daughter - Matilda (known by her second name, Caroline) - and her family.

Here the story may have ended. But there was to be a very surprising twist to the story forty years later.

The Western Front Assocation's Yorkshire branch visits the Italian Front

Every year, the Yorkshire branch of The Western Front Association runs a trip to the battlefields. These trips are very popular and, as well as visiting the 'obvious' locations of the Somme and Ypres, visits to less well-trodden battlefields are run. In 2015 the visit was to be the Asiago plateau in Italy. Arriving in Venice, the tour party - led by Battle Honours' Clive Harris - set off on the 80 mile route to Asiago. A break in the journey was made at Giavera where the party gladly stretched their collective legs and headed into the cemetery.

Above: Giavera Cemetery taken from the memorial. (Image author's collection, 2015)

Walking around the rows of headstones, it was obvious that virtually all the graves were of 'known' soldiers - among them a recipient of the Victoria Cross. It was only at the very front of the cemetery that two 'unknown' headstones were observed. In plot 5, row F (the very front row) was a private (regiment unknown) whose date of death was recorded as 27 October 1918.[1] Just a few paces away in plot 6, row F was the headstone of a soldier (rank and date of death unknown) of the Army Service Corps. This was intriguing.

Above: Row F of plot 5 in Giavera Cemetery showing the 'unknown soldier of the ASC'. (Image author's collection, 2015)

Realising that there would be only a few men of the ASC who would not have known graves, I headed to the rear of the cemetery to take a look at the memorial to the missing. There, between the Labour Corps and the RAMC, was listed the men of the Army Service Corps. The list could not have been shorter, it contained just one name. Driver ER Jordan.

Surely, it could not be that simple? There must be other possibilities. It had taken less than 60 seconds to identify the 'missing' soldier. Taking several photos, I decided to follow this up as soon as I arrived back home.

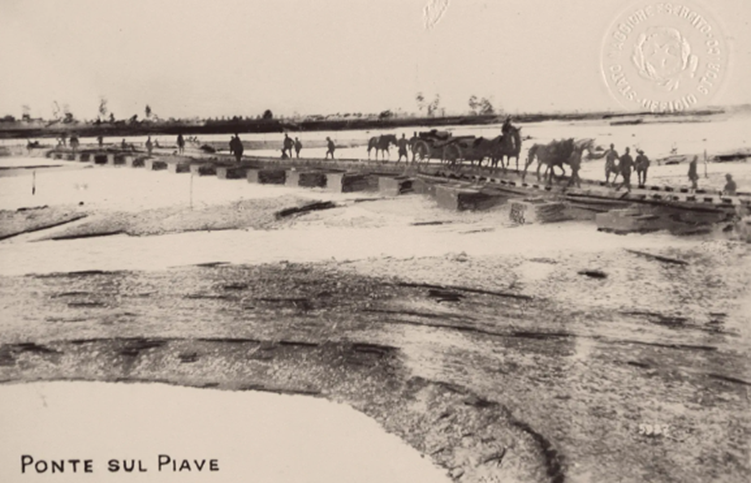

The branch trip continued for several days: we learned much about the campaign on the Asiago plateau, and other aspects of the campaign such as the crossing of the Piave river when - later in the trip - a visit was made to the 7th Division's memorial at Salettuol.

Above: The 7th Division's memorial: (Image courtesy of Michele Venturato / Google Maps, 2017)

Investigation into Ernest Robert Jordan

Returning home, I set about looking into fatalities among the ASC in the Italian campaign of 1917-1918. This resulted in a total of 208 men from the ASC and a further 58 from the RASC being listed by the CWGC as being buried or commemorated in Italy (the ASC became 'Royal' by warrant published on 27 November 1918). Apart from a large number of ASC men who are commemorated on the Savona Memorial (these men were lost when the HMT Transylvania was sunk on 4 May 1917) there was only one man who did not have a known grave - being Driver Ernest Robert Jordan.

The graves registration document (available on the CWGC web site) added the 'fact' that the unknown ASC soldier in row F 'probably' died on 27 October 1918. This clearly firmly ruled out the men from the Transylvania (and in any case, why would anyone washed ashore on the Mediterranean coast be buried here, close to the Adriatic?).

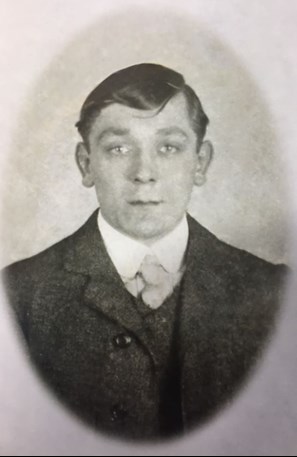

Knowing that most records were destroyed in the Second World War, I was not optimistic that I would be able to locate him in the 'burnt series' but nevertheless a quick search proved very fruitful. This confirmed that Driver Jordan had indeed been drowned in an accident on 30 October 1918 whilst crossing the nearby Piave river. Subsequent checking of the WFA's Pension Record Cards also confirmed the details from the burnt records.

Above: The Pension Record Card of Ernest Robert Jordan. (Image from the WFA's Pension Record Archive)

Ernest Robert Jordan - his story

Ernest Robert Jordan was born in 1883 in Bethnal Green, London. The family comprised of the father - John (a vegetable-market porter) and mother Ann together with Robert (from now on, the name he was known by ('Robert') will be used instead of his first Christian name) and Robert's brother (Henry). At the time of the 1891 census they lived at 19 Hague Street, Bethnal Green.

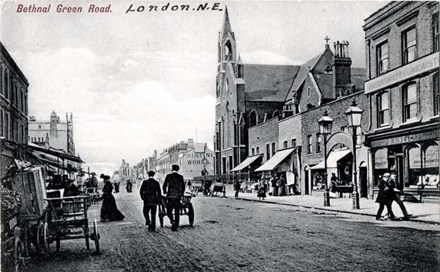

Above left: A Bethnal Green slum street, London, Circa 1900. (Image: wikipedia). Above Right: Bethnal Green Road. (Image courtesy of East London History Society)

It is understood that Robert attended Hague Street School, this would have been probably up to about 1900 - sometime before the photograph (below) was taken at the school.

Above: Geography lesson, Hague Street School, Bethnal Green, 1908

In July 1908 Robert was married at St Andrew's church, Bethnal Green to Matilda Florence Bradbury. He gave his occupation as a printer. The first of the couple's two daughters - also named Matilda - was born just before Christmas later that year.

They appear in the 1911 census still living at 19 Hague Street, Robert's occupation being noted as an envelope printer. A year later - in 1912 - Irene was born.

Robert joins the army

When the First World War broke out Robert did not immediately volunteer (obviously mindful of his young family) but did come forward as part of the 'Derby' scheme. At the time he was living at number 44 Russia Lane - the street adjoined the Bethnal Green Infirmary, this address being less than a mile away from Hague Street. His occupation was given as 'Printers Machine Minder'.

Above: Crutchlow's General Store at 1 Russia Lane, c1900. (Image courtesy of 'liminalhackney' via pininterest / twitter)

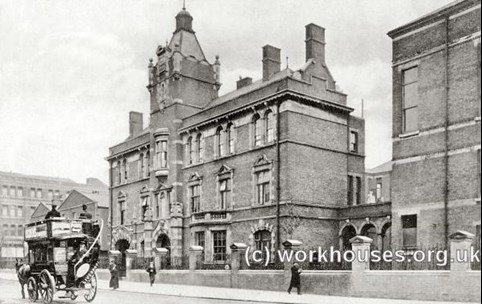

Above: Bethnal Green Infirmary, Cambridge Heath Road early 1900's (Image courtesy of Peter Higginbotham - www.workhouses.org.uk)

On 9 December 1915 Robert travelled six miles to Blackheath - south of the River Thames - to attest at the "number 2 Horse Transport Depot" at Blackheath. It is not clear why he travelled so far and chose this 'unfashionable' unit - perhaps he had been turned down elsewhere - his height was given as 5' 2¾" and this may not have been tall enough for some units. His medical record tells us he had 'deficient teeth' as well as a history of rheumatism, flat feet and hammer toes on each foot. These medical conditions would certainly have been enough for him to be turned down in the early days of the 'Kitchener' recruitment drive, but by the winter of 1915 the flow of recruits had dramatically slowed down and men who had previously been 'unsuitable' would now be welcomed into branches of the army where their infirmities were not so severe as to stop them being useful in some capacity.

This may explain why he was recruited into the ASC as a driver with the horse transport despite not apparently having any prior equine experience.

After attesting, Robert returned home and presumably continued to work as a machine minder for the printers. As a married man, aged 32 he was in group 38 under the Derby scheme which was one of the later groups to be mobilised. Group 38 of Derby scheme volunteers would have been called up in May 1916, but this didn't happen for Robert. From his records, we can see he was given some form of deferment for six months until November 1916, and then another deferment until May 1917. We can only speculate that this was either due him being in a vital war occupation (which seems unlikely) or due to the medical conditions highlighted when he attested in December 1915.

Eventually, the Army decided it needed Robert. On 12 March 1917 a letter was sent to 44 Russia Lane requiring Robert to present himself at the Central London Recruiting Depot at Great Scotland Yard at 9am on 27 March. So that Tuesday morning, Robert would have made his way (no travel warrant was issued) to central London and presented himself. It is likely that by this time the vast majority of men attending the Great Scotland Yard recruiting depot would have been wartime conscripts.

Great Scotland Yard August 1914 - at the height of the Kitchener volunteering drive. (Image courtesy of The Imperial War Museum / IWM Q42033)

Another view of the Central London Recruiting Depot (Image: Wikipedia)

Great Scotland Yard 2012. (Image courtesy of www.buildington.co.uk)

Robert was allocated to the 666 Company of the ASC which at that time had become part of the No. 1 Reserve HT Depot at Park Royal, Willesden.[2]

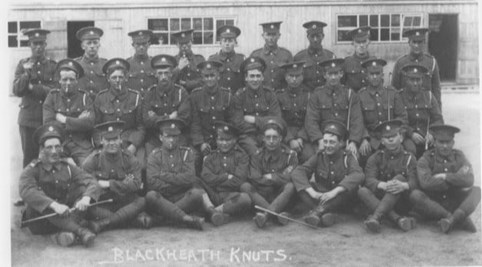

Above: 'The Blackheath Knuts'. A group of men at the Number 2 Reserve Horse Transport Depot, Blackheath. (Image courtesy of 'Postcards of the Army Service Corps by Michael Young via The Royal Logistics Corps)

After undergoing training for a few weeks, Robert found himself posted to the front - he was destined to join the 23rd Division's Army Service Corps component. He was part of a draft of men despatched to France in early May, crossing to France on the SS Viper. The ship was owned by G and J Burns. Prior to the war, Viper was employed on the company's Ardrossan-Belfast service.

Above: SS Viper (Image: Wikipedia)

Service on the Western Front

Robert arrived at Le Havre on 18 May 1917 and would have arrived with the 23rd Division within a few days. Although it is not clear which company he initially joined, it seems from his service record later in the war that he was part of the 192nd Company - there is no reason to suppose that he would have served in other companies during his service.

Above: The 23rd Divisional sign

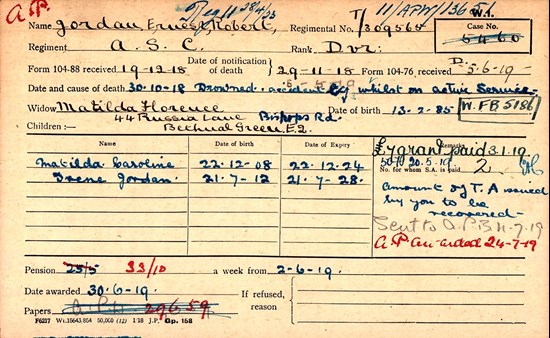

In June, the 23rd Division took part in the Battle of Messines. The ASC transport companies of the division (190, 191, 192 and 193) would have been responsible for supplying front line troops with food and supplies; this would have involved the collection of material from the rail-heads and transporting it to as near to the front as possible.

Above: Ration Supply. Lorries unloading a supply train at railhead to deliver to a forward refilling point. Although there is no evidence that Robert was utilised with motor transport, this image illustrates the method used by the ASC to move supplies from railheads towards the front line. (Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum IWM Q10450)

Above: Scene at a British water supply post on the continent c.1916. (Image courtesy of the National Army Museum 2007-03-7-163)

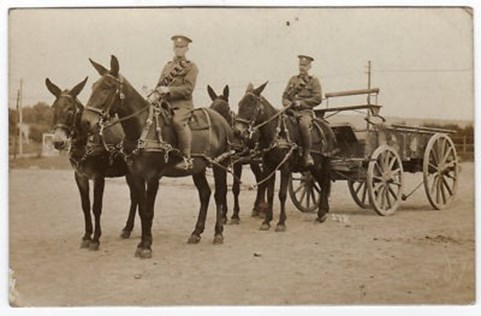

Above: Army Service Corps GS Wagon with Four Mules. (Image courtesy of www.worthpoint.com)

Whilst not 'front line' troops, this supply operation was far from risk free. The first fatality to the divisional ASC after Robert's arrival occurred on 2 June when Driver Harry Cotton from Mirfield was killed, with two other fatalities in the following four days.

No deaths among the division's ASC are recorded in July and only one in August but the ASC's divisional transport was badly hit on 21 September (when the division was involved in the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge). No fewer than eight men of the divisional transport train were killed and a further six wounded. All but three of these men were serving with the 192nd Company. Although the war diary makes virtually no reference to what happened (other than recording the casualties), it seems that a convoy of wagons was hit by German artillery fire. It is likely that this occurred nowhere near the front lines as the fatalities are buried in two cemeteries just two miles apart south-east of Poperinge (La Clytte Military Cemetery and Reninghelst New Military Cemetery).

Without doubt Robert would have known the men who were wounded and lost their lives. We don't know if he wrote home to tell his family of what life was like, but Robert would obviously have been relieved to have survived the incident unscathed.

To Italy

The 23rd Division was one of the British Army units that were sent to the Italian Front as a result of the Caporetto attack (which commenced on 24 October 1917). The journey was probably one of the highlights of Robert's life. The movement of troops has been superbly described by John and Eileen Wilks:

"...shortly after leaving the dreary fields of Flanders... they found themselves travelling [by train] down the Rhone Valley into Provence, past Avignon to Marseilles and the green hills sloping down to the intense blue of the Mediterranean Sea. The weather was warm and sunny, and the local inhabitants friendly. Then along the glorious coast of the Riviera. For most of them it was a revelation of another and very splendid world, even if they were travelling twenty-six men to a cattle truck.

"Crossing into Italy at Ventimiglia their route continued by the sea as far as Genoa where they turned away from the sunny coast to pass through the Apennines to the flat Lombardy plain, at this time of the year cold, frosty and misty."[3]

There is no room in this article to talk about the campaign in Italy during the remaining weeks of 1917 and during 1918, nor the campaign in the hills of the Asiago plateau which saw - for the British - the most intense fighting in this theatre. Much of Robert's service would have been mundane. Probably the most exciting part of his duties would have been taking his wagon and horses up the switchback road to the top of the Asiago plateau.

Above: Italian infantry and British troops advancing down the Val d’Assa mountain road, 2 November 1918 (Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum)

Other duties may have been at rail heads where supplies were brought in from France or the ports.

Above: Italian women employed by the British Army Service Corps loading barrels of beer on to railway trucks in Treviso November 1918. (Photograph by William Joseph Brunell, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum IWM Q 26003)

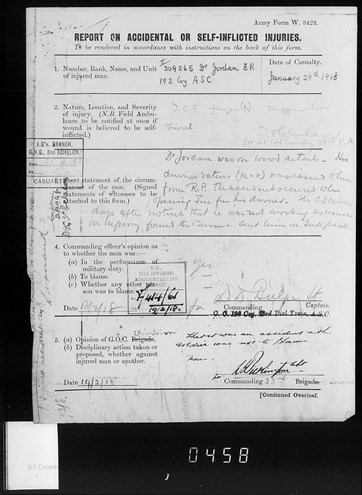

On 29 January 1918 Robert managed to injure his hand whilst opening a tin. It seems this became infected as he reported 'sick' ten days later and was subsequently admitted to the Field Ambulance. As this was potentially a 'self inflicted' injury documents and testimony from fellow soldiers was needed, but with the help of his colleagues, it was apparent that Robert did not injure his hand deliberately. In the bureaucratic way of the army, reports were obtained and a form completed which was signed off to say that he was not to blame for his injury.

Above: A page from Robert's service record 'Report on Accidental or self-inflicted injuries'. (Image via Ancestry)

Whilst this injury was fully recorded, a subsequent health issue was far less so: it appears that Robert suffered from a brief illness some months later when he was admitted to a field ambulance for seven days in May suffering from Tonsillitis.

Robert was allowed leave between 6 and 20 September. Although his surviving papers suggest he was a very well behaved soldier (there are no indications of any misdemeanours) the service record reports he arrived back at his unit on 26 September 1918. The fact that this did not result in any punishment suggests a clerical mistake at some point with this aspect of his record. It must be assumed that Robert used the fourteen (or twenty) days leave to return home and visit his wife and children. Little did they know that this would be the last time they would see him.

After a year in Italy, the British campaign culminated in an advance - along with Italian and French troops - in October. This led to the end of the war in this theatre. The 23rd Division took a full role in this, but again this article can't go into details of the division's activities, other than to say that, along with the 7th Division, they took part in a daring and superbly executed operation to cross the Piave river after first taking Papadopoli island in the middle of the river. These operations culminated in an assault on 26/27 October. The 23rd Division took, during this attack, 1,830 Austro-Hungarian prisoners and 29 artillery pieces.

Resupply problems at the end of the campaign

The advance by the allied forces caused problems with the supply chain and it proved difficult to keep supplies moving forward, particularly with the crossings of the swollen Piave river being limited in number. The bridge at Salettuol was put out of action on 28 October due to the heavy flow of water, and repairs having failed, it was decided to rebuild the bridge 30 yards downstream.

The congestion and backlog of supplies created by the difficulties in getting material across the Piave caused the British commander, Lt-General Lord Cavan, some concern, not least because of delays to the artillery which was unable to be rapidly pushed forward. Pressure would have mounted for the Army Service Corps to keep the flow of supplies moving.

It is against this background that the war diary of the 23rd Division's Army Service Corps refers to the unit being in Catena and supplying troops via a route through the village of Lovadina. The war diary describes how rations and ammunition were manhandled across the river and the Austrian (indecipherable but possibly 'army') damaged the main bridge at Sallettuol. The same entry (for 29 October) goes on to say how "rations for 70th Brigade, 103 Bde RFA and Divisional troops distributed to units. The rations for units across the Piave still on supply wagons - Everybody standing by to cross river."

The following day's entry is in much more legible handwriting. Perhaps the writer was in a calmer frame of mind, or at least less hurried. It reads:

"30th October - Supply sections of DT [divisional train] 68th, 69th and 70th Brigades got over the bridge with supplies and delivered to units on night 30th/31st. Div HQ at Bibano di Boto and 3 Coy [this is 192 Company - Robert's unit] did not get over till very late. One driver was drowned and two horses badly hurt. Baggage wagons refilled at Lovadina and returned to camp at 1.30am."

Above: Four images to illustrate bridging of rivers in The First World War.

(1) A British artillery battery crossing a pontoon bridge over the River Diyala near Baghdad in March 1917. This bridge was completed by the 71st Field Company, Royal Engineers (IWM).

(2) Bridge across the Piave. Italian Ministry of Defence: La battaglia di Vittorio Veneto (www.esercito.difesa.it).

(3) Men of the 2nd Battalion, Gordon Highlanders (20th Brigade, 7th Division) escorting Austro-Hungarian prisoners across a pontoon bridge over the River Piave, near Salettuol, November 1918. (IWM Q26704).

(4) Austro-Hungarian prisoners crossing the River Piave on pontoon bridge near Salettuol, November 1918. They are being escorted by troops of the 2nd Battalion, Gordon Highlanders (20th Brigade, 7th Division) (IWM Q26705).

Although not named, the above war diary entry refers to Robert Jordan. Within his 'burnt series' file there are three witness statements detailing what happened. The witnesses (Serjeant WJ Smith, Driver L Cooley and Serjeant A Moody) report how a supply convoy of the 3rd Company (ie 192 Company) was crossing the pontoon bridge with Robert being the driver of the lead pair of horses. When Robert's wagon arrived on the pontoon bridge, the lead pair shied and swerved and fell over the side of the bridge into the river. Driver Cooley (who was the driver of the wheeler pair) saw Robert thrown into the water and immediately disappear. His arm re-appeared above the water about 30 yards downstream before disappearing altogether. It seems that the wheelers were pulled over by the lead pair (it is unclear if they - or any horses ended in the water although the implication is that the lead pair did end up in the swollen river).

Tragically, nothing more was seen of Robert. His body was seemingly swept away not to be seen again.

Within a few days, the war in Italy ended. The Austro-Hungarians signed an armistice ('The Armistice of Villa Giusti') which brought fighting to an end on 4 November (although the order to cease fire came into effect on 3 November).

With Robert lost in the river, and his body not recovered after the war, Driver ER Jordan was named on the memorial to the missing for the Italian campaign. It seemed not to have registered with the Imperial War Graves Commission that the body of a soldier from the Army Service Corps that must have been found some days - or possibly weeks later - was that of Robert Jordan. The reverse of the Graves Registration Report Form, dated 30 March 1919 recorded the recovery of two bodies. One (the 'unknown Private' killed on 27 October 1918 who was buried in grave 1 of plot 5 row F) was stated to have been "Found in River Piave near where Maserada Bridge was, close to the Treviso bank."[4] The other (noted as being an unknown soldier of the ASC, Horse Transport) was "Found on bank of River Piave 200 or 300 yards south of the Unknown buried in 5.F.1." The Maserada bridge mentioned here is a vague reference to what is almost certain to be the Salettuol bridge.[5]

This unknown member of the Army Service Corps was buried in Plot 6, Row F of the cemetery at Giavera and the permanent headstone, when it was later installed, was detailed as that of an 'unknown soldier from the ASC'. The individual who completed the Graves Registration Report detailed the date of death as "probably" being 27 October 1918.[6]

The fact that Robert's body was never identified was probably highly distressing for his widow and children.

Matilda - Robert's widow - never re-married but did take in a lodger to help ends meet.[7]

Robert's two daughters, Matilda and Irene would probably only have had vague memories of their father, but still the story of Robert was passed down the generations with Carol Adams (the daughter of Robert's eldest daughter) passing the story on to her son Gavin.

Above: A locket, with Robert's photo in the centre, which has been passed down the generations. (Image courtesy of Carol Adams)

After undertaking the research upon my return from the branch trip, I made a submission to the CWGC in October 2015 which I realised would take some time to be considered, and ultimately (hopefully) approved by the JCCC (the part of the Ministry of Defence that is responsible for the identification of soldiers remains). The submission proved to be successful, and in the summer of 2018 (I later found out) Carol received a letter from the JCCC asking that she make contact with them in reference to her Grandfather. Carol was not given any further details as to the reason for the request, but was intrigued by the unexpected letter. The circumstances of Robert's death, coming at the very end of the war was well known in the family, but for almost exactly 100 years the whereabouts of his body had remained a mystery. The explanation, that after all this time Robert had been 'found and identified' was, to say the least a 'bolt out of the blue'.

Carol and Gavin attended the ceremony at Giavera in November 2018. Gavin writes:

The ceremony at the Giavera cemetery was a very overwhelming experience. To be given the opportunity to pay our respects to a family member who gave their life, so that we may enjoy the one we have was a great privilege. That 100 years on the military still continue to honour their dead with the care, respect and dignity that they do was a deeply humbling experience, and one that neither of us will forget. It reminds us that in troubled times there is much to be proud of in our country.

Above: Carol and Gavin Adams (centre) standing behind the headstone of Robert Jordan, November 2018. (Image courtesy of the JCCC / MoD)

Above: Carol Adams - Robert Jordan's granddaughter. (Image courtesy of the JCCC/MoD)

Bethnal Green today

The streets where Robert lived are much changed. Hague Street and Russia Street both exist, but are much shorter than they were a hundred years ago. The slum houses have been demolished - either by the Luftwaffe in the Second World War or by clearances in the post-war period. Little of the area would be recognisable to the Jordan family if they were able to re-visit the area a hundred years on, other than the original pubs at the end of many of the roads!

Above: The Blind Beggar Bethnal Green - later infamous with its connection with the Kray twins.

Robert is seemingly not commemorated on a war memorial in the UK. Perhaps his name was on a memorial in his local church - St Andrews on Viaduct Street, or perhaps there was a street memorial that named him, similar to the one that still exists in nearby Cyprus Street.

Above: The War Memorial in Cyprus Street, Bethnal Green. (Image courtesy of Tim Le / Google Maps)

The local church, St Andrews - where Robert and Matilda were married - no longer exists, it may have been destroyed during the Blitz in the Second World War. The area between - and south of - Hague Street and Viaduct Street (the site of St Andrews) is now an open space called Weavers Fields.

The Piave today

On the site of the pontoon bridge where Robert was thrown into the water is a modern bridge. Adjacent to the bridge is the 7th Division memorial commemorating the division's crossing of the Piave. Unfortunately there is no memorial to the 23rd Division here.

The bridge (in the background) from the western bank of the Piave to the Papadopoli Island. To the left (but out of shot) is the memorial to the 7th Division. (Image courtesy of Google Streetview, 2011)

Orientation

Many readers may be unfamiliar with the locations mentioned in this article. By clicking THIS LINK it is possible to see the locations of Giavera Cemetery, Catena, Lovadina and Bibano - these later towns being mentioned in the ASC company war diary mentioned above.

Equally, Bethnal Green is probably unfamiliar territory to most readers. By clicking THIS LINK it is possible to see how far apart Russia Lane and Hague Street are (but of course, the road area is much changed since Robert Jordan's day).

Article by David Tattersfield, 2019

Footnotes

[1] A total of 23 privates were later found to have died on 27 October who had no known grave.

[2] Horse transport training for the ASC was provided by three Horse Transport depots, in Aldershot, Bradford and Woolwich. A reserve Horse Transport Depot (661, 662 and 666 companies) formed initially at Deptford but later moved to Park Royal, Willesden.

[3] Due to the shortage of rail capacity, some motor vehicles of divisional supply columns made the journey from northern France to Italy by road. This took ten days. See 'With the Mad 17th to Italy' by Major EH Hody, RASC (London: G. Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1920)

[4] It is unclear how the body of the soldier was 'known' to have been killed on 27 October, unless this was an educated guess.

[5] Salettuol is the village on the bank of the Piave - the river here is at its maximum width. The village is in the municipality of Maserada - which itself is in the Province of Treviso.

[6] Clearly, as was later discovered, the speculative date recorded on the form was found to be incorrect, which suggests that the recording of information on these forms can sometimes be misleading.

[7] The lodger known as Uncle Bill was William Albert Crossen, a pre-war regular who joined the army in 1903 and had served overseas and at home. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War he had transferred from the East Kents to the West Yorkshire Regiment, and was with the 1st battalion until January 1916 when he became 'time expired'.

Acknowledgements

Carol and Gavin Adams

Craig Suddick

Jonathan Knowles, Lt Col (Retd): Secretary RASC & RCT

Further reading

The British Army in Italy 1917-1918 John and Eillen Wilks (Barnsley: Leo Cooper, 1998)

Across the Piave: A Personal Account of the British Forces in Italy, 1917-1919, Norman Gladden (London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1971)