A Father’s Search

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Father’s Search

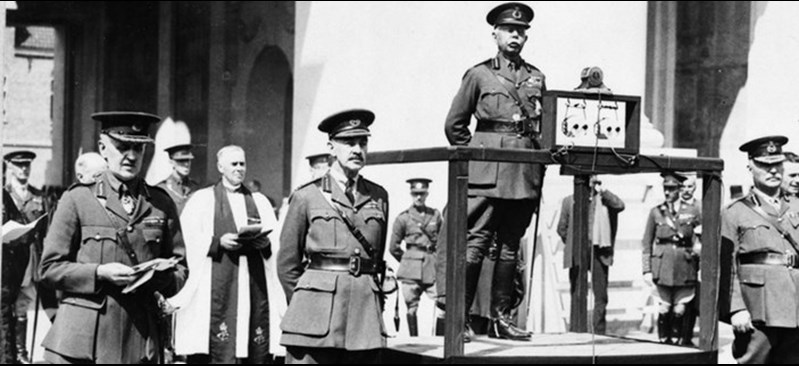

For many families of ‘the missing’, the absence of a known grave in the immediate aftermath of the war was unbearable. It would, of course, be some years before the Memorials to the Missing were constructed after the war. Field Marshal Lord Plumer, when unveiling the Menin Gate in 1927, acknowledged the void that many families of ‘the missing’ would feel, with no focus for their grief with the words ‘He is not missing: He is here’.

Above: Field Marshal Lord Plumer at the unveiling of the Menin Gate in 1927. CWGC

But in the early years after the war, there were no memorials to provide any sense of solace to those who had not a physical grave to visit, if they were able to, or even a photograph to cherish.

Only a tiny minority of relatives would have the means to take any practical action to search for their loved ones’ remains – some would go to great lengths to do so. The search by Rudyard Kipling and his wife, Carrie, for their son, John Kipling, reported missing at Loos in September 1915 is probably the best known example.

But the efforts of Colonel Frederick James Hayter and his wife, whose son Eric, had been killed in March 1918 possibly eclipses even that of the Kiplings and well merits the description of ‘this quiet persistent man and his more quiet and more persistent wife’ found in correspondence in the CWGC file of the case.

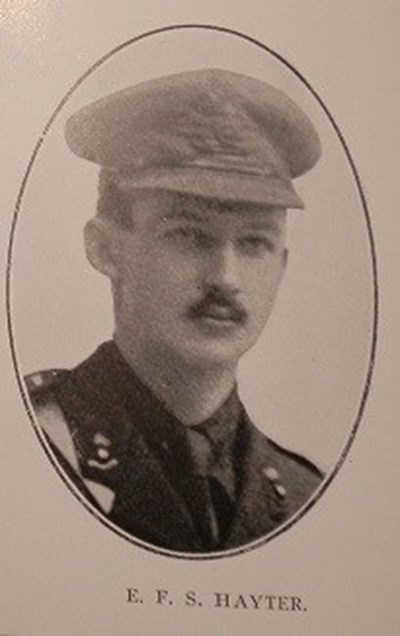

Frederick James Hayter was born in 1860. He married Helen Frances Corbett in Victoria, Australia in 1892. A military man, he was also a man of some means, although little is known of him. Their son, Eric Francis Seaforth Hayter, was born in Australia in 1892. He was educated in Australia and became an electrical engineer there.

Eric returned to Britain, travelling first class, on the P&O steamship, Medina, arriving at London on 3 April 1916. He then obtained a commission in the Royal Field Artillery. He crossed to France later that year, seeing action in the latter part of The Battle of the Somme. By 1918, Eric was serving in the 87th Battery (Howitzer) of the RFA.

Above: Eric Francis Seaforth Hayter. Photo - IWM

On 21 March 1918, the Germans launched the Spring Offensive under the code name ‘Operation Michael’. Eric was at that time in the front line near Lagnicourt. Despite a terrific German bombardment Eric and his men remained with their guns, firing off all their ammunition at the advancing Germans. Unable to bring up more ammunition or to retreat due to the heavy German bombardment Eric ordered the guns spiked, rendering them useless and denying them to the enemy. With the German infantry closing in Eric led his men as they fought on with small arms until they ran out of rifle ammunition at which point, they were overwhelmed by the German attackers. All but four of the artillerymen were killed, the survivors being taken prisoners of war.

A subsequent report from one of the survivors indicated that:

'Second Lieutenant Hayter was during this time wounded on the face and had a part of his right hand shot away, but continued to hearten his men and would not hear of giving in. He was known to have said more than once previously that the Germans should never take him prisoner , and they certainly did not do so, because when they were coming within pistol range he deliberately stood out, revolver in his left hand, and by gesture invited the Germans to come on and take him, but this they had no intention of doing, for they shot him through the head with a rifle bullet.'

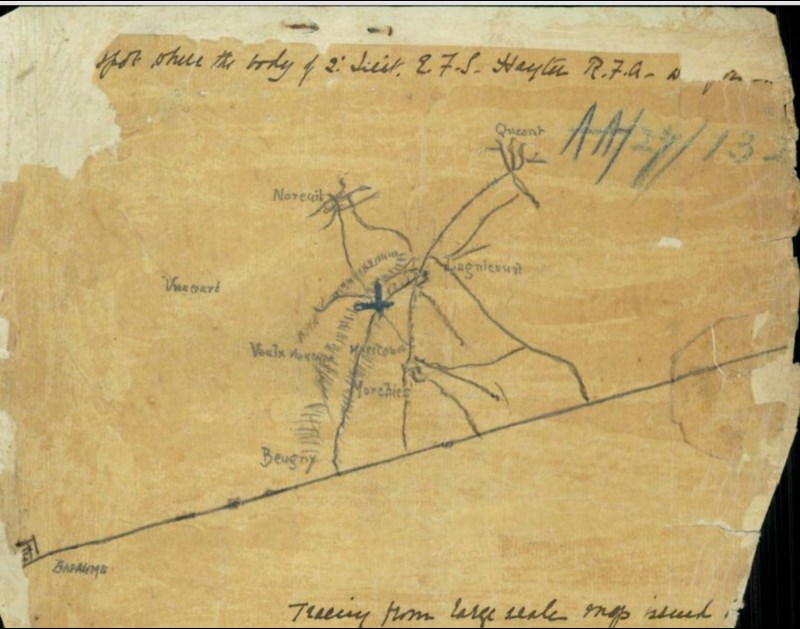

Later in 1919, Eric’s aunt would write to inform the Imperial War Graves Commission that an Alsatian private soldier had sent a hand-drawn map showing the location of her nephew’s grave to the family.

Above: the hand drawn map received by the family. CWGC and the ruined village of Lagnicourt. Photo - AWM

His parents, Frederick and Helen, arrived at Liverpool on 12 March 1920, on board the SS Nestor. Before their return, Eric’s aunt had made enquiries about the location of Eric’s grave through the International Red Cross but there was no record of any grave being registered. His aunt was reassured by the Graves Registration and Enquiries in February 1919 that:

'In the final clearing up of the battlefields it is expected that the identity of unknown graves will in a great number of cases be established and in addition many graves will be found which to date have not been reported and registered by my officers.'

By 29 March 1920, Eric’s parents were now resident in Sydenham, London. His father wrote at some length to the IWGC regarding his son. In this letter, he provided details of his son’s height and dental records (gold crowns), plus details of the wounds that he was reported to have received. In response in April 1920, it was suggested to Eric’s father that a potential gravesite of his son had been located. Remains had been found at a map reference of 57.C.30.a.4.5, with the grave relocated to Queant Road Cemetery bearing the inscription of ‘An Unknown British Officer’.

Whilst it was suggested to Eric’s father that “it appears to be extremely likely that this is the grave of your late son”, Colonel Hayter was not entirely convinced. He pointed out that the map reference was at least a mile from the location of his son’s position on 21 March 1918 and indicated that he would need 'some convincing proof of identity' to accept that this was indeed his son’s grave.

The first exhumation to take place was then carried out on this grave. The report indicated that the officer was likely of above average height, had a crack in his skull and no teeth had been found. This led to a letter being sent to Colonel Hayter on 17 May 1920 which concluded:

‘As there appears to be little doubt that these are the remains of 2/Lt. E F S Hayter, it is proposed to accept that this is the grave in which he was buried, namely Queant Road British Cemetery, Plot 7 Grave 9’.

Colonel Hayter expressed some doubts about this conclusion primarily because there was no mention of a bullet wound to the head and his son has a full set of teeth, including some gold crowns. He also pointed out the map reference of the location in which his son was killed was 57c.C 29(a). By June 1920, it was generally accepted that the grave in Queant Road Cemetery was not that of 2/Lt Hayter and a further special search of the area indicated in the sketch map (referred to above) would be made. A file note dated 20 July 1920 refers to reports from France, commenting ‘they seem to have indulged in an orgy of exhumation’.

Above: A trench map of the area

Above: A trench map of the area

By November 1920, Colonel Hayter was no further forward despite having visited the area earlier in the year. During this visit, four graves had been exhumed at Beaulencourt British Cemetery for identification purposes. A report from France indicates that Colonel Hayter himself exhumed a grave in Lagnicourt Hedge Military Cemetery – all with no positive result.

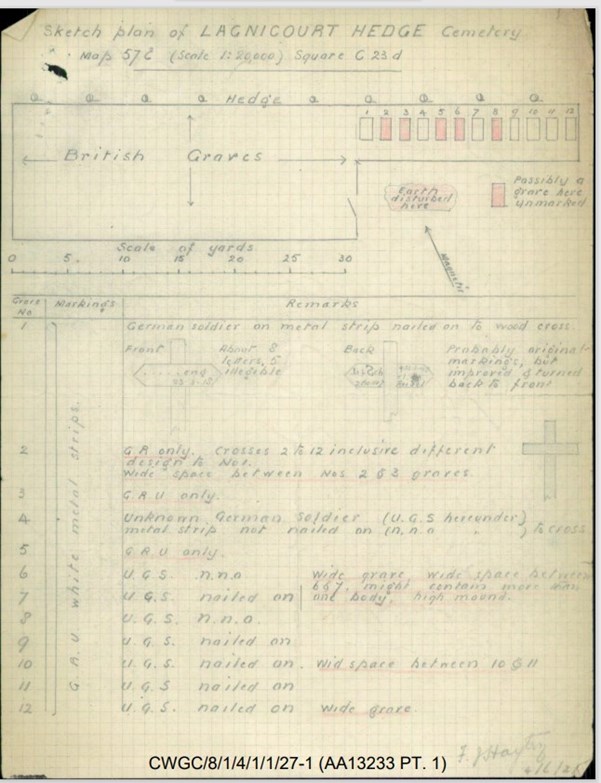

By May 1921, Colonel Hayter was again in France and asked that the graves of twelve ‘unknown’ German burials in Lagnicourt Hedge Cemetery might be exhumed as they might actually contain the bodies of British men. Initially this request was refused but Colonel Hayter persisted.

Above: Colonel Hayter’s sketch plan of Lagnicourt Hedge Cemetery

Authority to carry out exhumations of the twelve graves identified was finally given in August 1921. On 6 August 1921, exhumations took place with Colonel Hayter present. Although none of the remains proved to be those of his son, the exhumations did identify that there were in fact fifteen German dead buried there, and five British dead. Information received from Germany enabled the identification of the five British soldiers.

In the following year, Colonel Hayter identified a further area of ground which he felt merited investigation, providing a further sketch map of the area. He went out to France to search this area with no success.

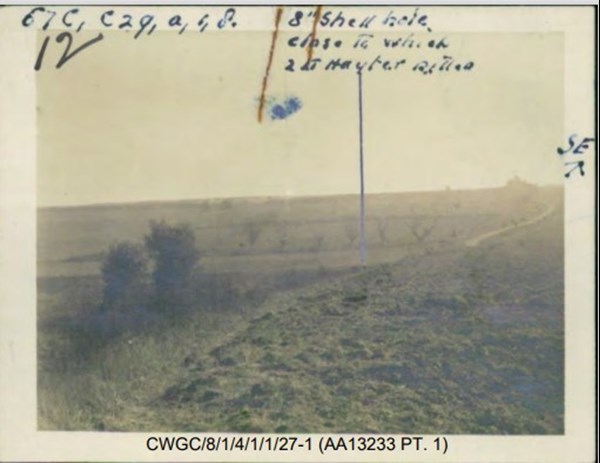

Above: a photograph in the CWGC file relating to where Lt Hayter was killed.

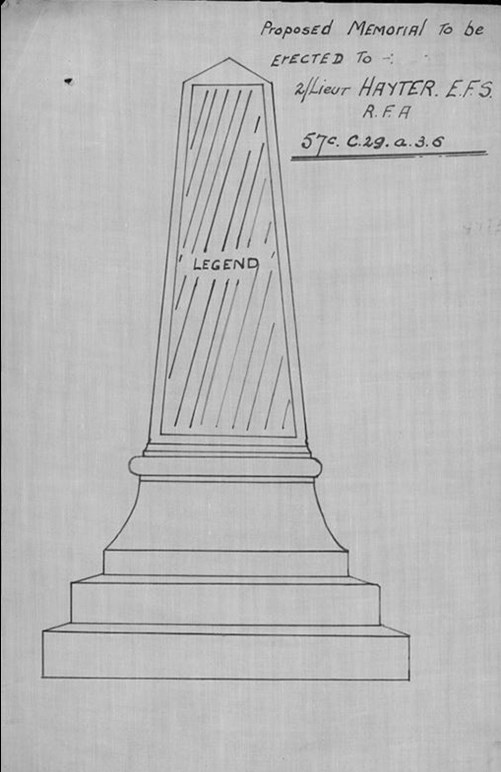

By 1923, it appears that Colonel Hayter had accepted that it was unlikely that he would ever locate the remains of his son. Consequently, he began to make arrangements to have a private memorial erected near the spot where he believed that his son had fallen on map reference 57C C29 a 1 8. However, he was unable to purchase the precise area of ground he sought but settled on a piece of ground a few yards away.

Above: the drawing for the private memorial

In September 1924, when the contractor began to break the ground for the foundations of the memorial, he came across a body buried about three feet below the surface. Amazingly, the body could be identified as that of 2/Lt Hayter, largely due to the presence of the gold fillings and badges of rank.

Above: the private grave memorial erected.

The memorial was maintained as an isolated grave by the family and the CWGC until 1969. By this time, there were no living relatives. Colonel Hayter and his wife had both died in the 1940s. The decision was then taken to concentrate the grave to a cemetery in Lagnicourt. 2/Lieutenant Eric F S Hayter now lies in Lagnicourt Hedge Cemetery.

Above: The area today, the road is the approximate site of the memorial and leads directly to Lagnicourt Hedge Cemetery.

Above: the headstone for 2/Lt Hayter and Lagnicourt Hedge Cemetery. Photo - CWGC

Article contributed by Jill Stewart

Hon Sec. The Western Front Association

Sources

Second Lieutenant Eric Frances Seaforth Hayter, CWGC

CWGC file –CWGC/8/1/4/1/1/27-1 File AA13233 Pt.1