A Mother’s pilgrimage to Ypres 1921

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A Mother’s pilgrimage to Ypres 1921

Private Joseph French was born in Dallas, Morayshire in December 1895, the son of William and Elizabeth French. The family later moved to live in Garmouth, Morayshire. Joseph enlisted in the Morayshire Territorials – the 6th Seaforth Highlanders – in 1912.

Above: Joseph and his friends at camp, pre-war. Joseph is sitting, front row left, holding a bottle.

Although Joseph was mobilised on the outbreak of war along with the rest of the battalion, he did not go to France until December 1915, when he joined the 6th Battalion.

Above: Joseph French

In June 1917, Joseph got leave which he spent at home. On his return journey to the front line, he wrote from London on 1 July 1917 to his mother:

Dear Mother,

…….. I arrived here in London today about ten o’clock am after a fairly decent journey and not much the worse only a wee bittie homesick kind yet. Only that will soon pass away once I am back with the boys. I felt the coming away getting hard this time and although I was maybe looking pretty bright I was not altogether alright. Well I hope the war will soon be finished and us all back again very soon to bonny Scotland and home……

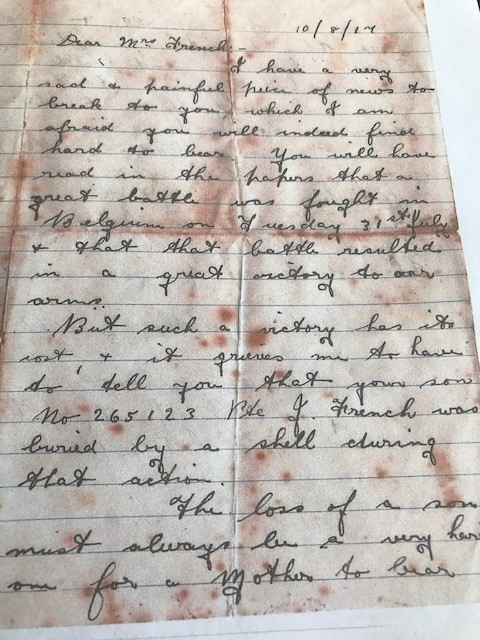

Sadly, this was not to be - Joseph was killed on 31 July 1917, the first day of the Third Battle of Ypres. He was buried in No Man’s Cot Cemetery. The news of Joseph’s death was broken to his mother in a letter from the Battalion Padre.

Above: The letter from the Padre received by Joseph’s mother after his death.

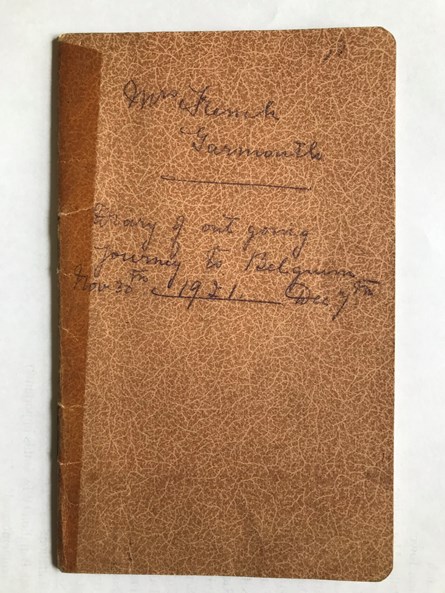

In December 1921, his mother undertook a pilgrimage to Joseph’s grave and throughout her journey, she recorded her experiences and thoughts in a diary.

Elizabeth French was a remarkable woman. Despite little formal education - she had worked as a cowherd from an early age – she wrote an extremely eloquent account of her pilgrimage which was later published in the ‘Northern Scot’ local newspaper over a few weeks in 1922.

Above: the diary in which Elizabeth French recorded her experiences during her pilgrimage.

‘….At last, and after innumerable fears and hopes, the long, sad journey to a Seaforth grave in distant Belgium is an accomplished fact – an undertaking which no doubt to quiet home dwellers in Moray at one time seemed utterly impossible, although since the war ended it has been to them the Mecca of all their hopes.

……Since my son’s death in action on 31 July 1917, near Ypres, I have always wished to see his grave, and when a letter setting forth the ease with which relatives could visit war graves under the auspices of the Y.M.C.A’s Red Triangle League appeared in ‘The Northern Scot’, I wrote at once to headquarters in London explaining my circumstances briefly. Almost at once I received an answer stating that my case was being considered. A form was enclosed to be filled in by my minister, who was also asked to write a short account of my circumstances and if he considered my case eligible for a grant from the League. This was done, and shortly afterwards I was informed that I had been awarded a grant for the journey, the cost being estimated at £13 5s 10d. A passport etc were enclosed with instructions.

…….Here let me say that intending travellers ought to have a small photo ready to affix to the passport, which the local police officer has to fill in and sign and also the exact location of the grave, which can be got by applying to the Graves Commission, Baker Street, London.

……All formalities having been gone into, I received a warrant which enabled me to get a return ticket from Garmouth to St Pancras Station, London via the North British and Midland Railways – a rather unusual route for travellers from Moray. I was requested to travel to London, and arrived on December 1 at Euston Hostel in readiness to proceed to Belgium early on the 2nd’.

Her journey was all the more remarkable as she was travelling alone (her husband, William, had died in January 1920, aged 62) and she had probably never travelled far from her native county.

‘……”This is the Ypres party here” our host said, and led me to a table where three ladies and a young man sat. We quickly ascertained where we had all come from and which cemeteries were to be visited. Our party consisted of an old lady from Leigh, near Manchester, and her son of twenty on their way to visit the eldest son’s grave at Coxyde Cemetery, two sisters from Pendleton, Manchester, on the way to Nine Elms Cemetery, Poperinghe, to visit the grave of their only brother who fell in action after being only nine weeks at the front, and myself.

…….It was nearing eight when a smiling guide approached our table and told us it was time to move. It was still raining – it had been all night – as we walked to Euston Station and took the underground morning train. This was another new experience for me, although to my companions it was nothing new, and they smiled indulgently when I told them so.’

The crossing to Ostend was not calm and Elizabeth and her travelling companions all suffered from seasickness on the crossing but:

‘……Soon the awful up-and-down motion ceased and we began wearily to gather up our belongings, resume hats and wraps, and bidding our guardian good-bye, made our way on deck to watch for our Red Triangle guide. Anxiously we scanned the crowd on the landing stage, until just at the end of the gangway we picked him out, noting with pitying eyes that the khaki sleeve at his right side hung empty, poor fellow. A splendid specimen of English manhood he must have been ere war had marred and maimed him for ever. ….Oh how glad we were to reach terra firma again and to hear our guide’s cheery greeting “Come along, Red Triangles, follow me”’.

From Ostend, the group boarded a train for Ypres. The journey was difficult as it was intensely cold and it was impossible to see out of the carriage windows which were frozen over. But during the journey, Elizabeth recorded that:

‘…..Until now I, and I think the others of our party also, had kept thoughts of our destination at bay. Now it gripped us relentlessly, and our little jokes and pleasantries fell from us. We sat in silence as the train sped on, ‘seeing visions and dreaming dreams’ of those young heroes of ours who had led the way before us, whom we had nursed in their infancy, played with and reproved in their careless childhood and youth, watch with fear in our hearts as they marched lightly away to the wail of the bagpipes on that never to be forgotten 4th of August to meet death on these battlefields through which we were now speeding.

Many, many times have I vainly tried to reason out the eternal why and wherefore of such awful happenings, and with ruthless force it gripped my heart again. Why had this dear lad whose grave I had journeyed so far to see, who had just opened his eyes on the Lossie’s banks on a December morning twenty six years ago, and had lived a quiet and blameless life, been fated to come to this far away land of Belgium to die?

Just as I had reached the blank wall of unanswering silence again our dear old lady whispered with white lips ‘My poor Peter, he had to come a long way to die’, just the question which I had been asking myself mutely, and we drew together, and until Ypres was reached, we spoke in hushed tones of our boys, telling their all too short life stories and their little youthful pranks. It comforted us all and helped to draw our thoughts from these awful fields we knew lay out there about us.

Finally, the train arrived at Ypres.

Above: Rue de la Gare, Ypres 1921. Photo - IWM

‘…with beating hearts, we watched the scattered lights of the ruined town of Ypres appear and disappear as we slowed down. There was a small crowd in the station, from which a figure muffled in a sheepskin coat and muffler detached itself and came towards us. Quickly he opened our door and helped us out…he led the way out of the station and guided us at last into the ruined city of Ypres.

…At last, lights gleamed before us, and after guiding us in turn over a small plank bridge – we found out in the morning that it was a partly filled in trench we had crossed – Archibald (the Red Triangle Guide) mounted a few steps and pushed open a door, letting in a blast of icy wind which blew the curtains about the door inwards and nearly extinguished several swinging lamps in the large dining room.

….”Oh, how cold you must be. Come to t’ stove at once,” said another voice pityingly, and turning, I found a lady with prematurely grey hair and saddened eyes holding out a welcoming hand. There seemed to be a crowd about the tables and a babble of talk was going on as we thawed our numbed hands and feet before one of the fine stoves which seem to be a feature of Belgian households.

As soon as dinner was over, we formed a wide circle about the huge fire and quickly found ourselves at home. …..Never, even in Dallas, have I felt anything like the cold in Ypres, and the worst was yet to come.

……Oh that terrible night of cold! I do not think any of us will ever forget it. The sheets were like ice and ice, solid to the very bottom was in our jugs. In fact, jugs generally split in two there, we were informed. Our little old lady suffered terribly in the other bed as she was still weak from a recent severe operation. We had plenty of blankets and clean and comfortable beds too, but nothing could keep out the awful cold.

The thought which haunted me that first night was that what we were suffering, at least in shelter and comparative comfort, our poor laddies suffered in the open. In the trenches and on the bare hillsides they had endured this bitter weather in all its variations, and my wonder now is that so many of our surviving boys returned with sane minds and in many cases cheery souls.’

On the next day, Elizabeth explored a cemetery in Ypres:

‘…Nearby was the British cemetery and here, had time and the penetrating cold permitted, we could have wandered for hours among the long rows of wooden crosses and smoothly cropped grassy strips of graves. Here and there were to be seen wreaths and crosses indicating those graves which had been visited by relatives. The crosses vary according to regiments, the Seaforth cross being the plainest of all, small and black, with metal strips on which are stamped the names and battalions of the men and also the date of death.‘

Although it is impossible to be certain which cemetery Elizabeth may have visited that morning, it may well have looked like this.

Above: Ypres Reservoir Cemetery post war. Photo – Michelin Guide to Ypres.

After a morning in Ypres, Elizabeth set off to visit her son’s grave.

‘On arrival back at the hostel, I was advised to have everything in readiness as Tommy would take me to Boesinghe, a distance of eight kilometres (about five miles) after lunch. I brought from our room a wreath of holly and other greenery which I had carried from home for my grave, made for me by a father who had given two sons to his country’s cause. On my family’s behalf, I purchased from Mr Marston a lovely cross of white artificial flowers which they wished me to lay on their brother’s grave.

As soon as lunch was over, Tommy and I set off and only when I was stepping into the car, did I remember that I had never been in one before. I could recall an occasion when on his last leave I had laughingly said so to my son and his answer ‘Never min’, mother; wait till I come hame again an’ I’ll tak’ ye a joy ride myself’, and my joy ride was to visit his own grave.

‘Now be sure to grip the seat well as it’s an awful road’, Tommy said as he muffled us both up and truly it justified his warning. Dodging a shell hole here and a huge pile of debris there, sometimes with one wheel up and other deep in a frozen rut, we tore through the town, where even my ignorance of warfare read easily the awful carnage once enacted. Our way led up by the Cloth Hall and the Cathedral also the Reservoir. It seemed to me as we sped on that human ingenuity would never cope with the havoc, and that Ypres must forever lie as one of the ruined cities of the world. And Ypres is only one of many.

….Tommy stopped the car where a rutty track led to where men with horses were unearthing the debris from a battlefield and piling the wire entanglements, sheets of battered zinc and other metal remnants in a huge heap. ….leaving the track we crossed several ploughed fields before reaching the lonely little spot I had travelled so far to see.

A small white gate, with a board on which was painted ‘No Man’s Cottage Cemetery, British’, gave us admittance, and as we stepped inside my kindly smiling young guide handed me my wreaths, and with tears in his eyes and a break in his voice said in a husky whisper ‘Give me your passport and I will find your grave…….’.

Elizabeth would write ‘Of the all too few minutes precious to mothers beyond all others I cannot write lucidly’ but she did indeed write a lucid and poignant description of the location of her son’s grave:

‘It lies on the ridge of a long, bare slope below which the war had raged bitterly and for many months. Away across a wide valley arises another ridge, and in every direction far as the eye can reach rise the white columns of stone erected in each of the British cemeteries at the cessation of hostilities. All round lie trenches, which in course of time will no doubt be filled in, and on the left, lies ruined Ypres. ‘No Man’s Cot’ contains in all only three rows of crosses. I do not think there are more than a hundred men buried there altogether. There is no road to it yet, even the permanent fence has not been erected, simply a strand or two of barbed wire encloses this quiet and lonely little God’s area where surely our boys sleep as quietly as they would at home in our own kirkyards in Morayshire. At the extreme rear of the cemetery, in a little square of fence, stands the memorial recording the sacrifice of the men who lie there, and over all the bitter winds sweep in winter and the sunshine falls in summer, while they sleep unheeding, and for them there is no more sun nor moon, life’s fitful fever is o’er. With numbing fingers, I tied my white cross to that other cross below the seven names.......Tying my holly wreath also, for a rising wind warned me that they would not lie long on the grave, I took my last lingering farewell and turned away.’

Elizabeth had but a few minutes at her son’s grave…...but family members have also been able to visit since then.

Above: No Man’s Cot Cemetery. Photo CWGC 2021

The author of this article has visited this cemetery on several occasions, the last of which was in April 2017 with colleagues from The Highlanders Museum, when Elizabeth’s description of her visit to the cemetery was read out – it was a truly powerful and moving experience.

Elizabeth French continued to write articles and verse until her death in 1927 at the age of only 53 years.

Article contributed by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Jane Webb for access to family papers and photographs