Amongst the First To Fall - Early Casualties of the Royal Flying Corps in August 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Amongst the First To Fall - Early Casualties of the Royal Flying Corps in August 1914

Death was not a stranger to the Royal Flying Corps even before the British Empire commenced hostilities against Germany on 4 August 1914. Between the founding of the Corps on 13 May 1912 and the outbreak of War twenty-seven months later the Military Wing suffered the loss of twenty airmen in aeroplane accidents. Nevertheless, the RFC carried on with its task of developing an efficient air arm to support the Army in whatever might occur in the future.

When War was declared, the Military Wing of the RFC comprised 147 officers, 1097 men and 179 aeroplanes. There were 7 aeroplane squadrons: No 1 Sqn at Brooklands was in the process of converting from being ‘The Airship Detachment RFC’; No 2 Sqn was moving from Montrose in Scotland to Netheravon; No 3 Sqn was at Netheravon, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Flights of No 4 Sqn were at Eastchurch, and ‘C’ Flight was at Netheravon; No 5 Sqn was at Gosport; No 6 Sqn was at South Farnborough; and No 7 Sqn was at Farnborough, where it was disbanded on 8 August to provide additional staff to the other squadrons.

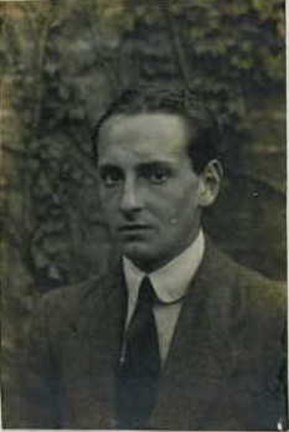

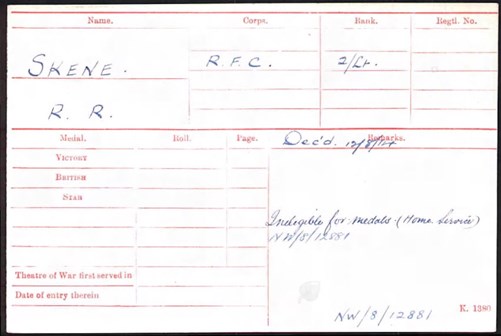

Robin Reginald Skene was born in London on 6 August 1891, and was an eminent pre-War pilot, who trained at the Bristol School at Brooklands before qualifying for Royal Aero Club Certificate No 568, issued on 21 July 1913. Even before he had his Certificate, he entered the London-Paris-London air race, but he did not participate. He gained a measure of fame by being the first British pilot to loop an aeroplane and worked as an instructor at the Bristol School. On 15 November 1913 he was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant in the RFC Special Reserve. He entered the London-Manchester-London Air Race in June 1914, but had to withdraw, perhaps as he joined the Martinsyde Company as a pilot in late June, replacing Mr Vincent Waterfall, the previous pilot, who had joined the RFC (see below). As War drew near, Robin continued to instruct pupils on Martinsyde machines, but was ordered to join No 3 Sqn when the Army mobilised. No 3 Sqn was commanded by Maj J M Salmond, and its pilots included Capt Philip Joubert de la Ferté and Lt Archibald Christie.

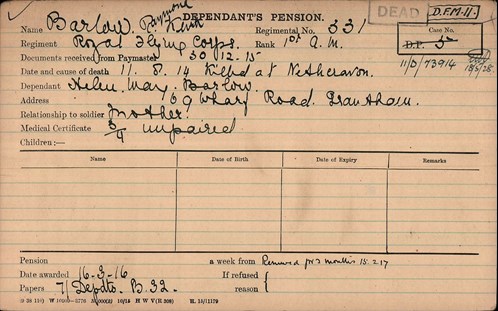

Raymond Keith Barlow, nicknamed ‘Cuth’, joined No 3 Sqn in July 1912 and served at Netheravon alongside AM J T B McCudden (892) who went on to become a Major with the VC, DSO, MC and MM. In his autobiographical account Five Years in the Royal Flying Corps, McCudden wrote: “Barlow was an awfully interesting fellow, having in his early life set out to explore life for itself, and he had had many experiences during his rovings. He was a really genuine soul and, moreover, a philosopher. His views on the future of flying have since turned out to be remarkably sound. Barlow was very keen on flying, keener, in fact, than I was myself, if that were possible.”

When the BEF crossed the English Channel, Nos 2, 3 and 4 Squadrons, plus RFC Headquarters and an Aircraft Park, accompanied it on 13 August, while No 5 Sqn was to follow shortly after. The squadrons concentrated at Swingate Downs on 12 August to prepare for their flight from nearby Dover to Amiens the following day.

About a quarter past five o'clock Second-Lieutenant Robin R Skene, of the 3rd Squadron, accompanied by Raymond Keith Barlow, a first air mechanic in the corps, ascended from Netheravon sheds in a Bristol monoplane which was ready for active service. That the aeroplane was not loaded to a dangerous extent is shown by the fact that several other machines left the school carrying similar weights without accident. The monoplane had not proceeded far on its journey when the pilot in taking a left-handed turn banked sharply. The result was that the machine lost speed and dived vertically to the ground. Lieutenant Skene was found under the wrecked monoplane, while Barlow was pitched clear of it. Both died before medical aid could be obtained....The Squadron Commander of the Royal Flying School said that after the accident he examined the machine, which was completely wrecked. It had evidently fallen almost vertically but not from a great height. The controls were all intact. The machine was heavily loaded for active service, but was able to fly. He understood that Lieutenant Skene was a capable pilot.

Arthur Frederick Deverill, first air mechanic, Royal Flying Corps, an eyewitness, said he attributed the accident to the loss of speed in banking. This was the first time the machine had been so heavily loaded, but if precaution had been exercised flight would have been safe. Several machines left that day with the same load. The monoplane was at the height of about 150ft or 200ft when it dived vertically to the ground. The engine was running at full speed until the fatal turn.

The report in Flight after the accident concluded that Lt Skene was used to flying lightly loaded Bleriots and a Martinsyde with a 120hp engine, and perhaps did not appreciate the poor climb rate of a Bleriot XI with two persons on board, and loaded with stores deemed necessary on active service: a revolver, maps, binoculars, spare goggles, a roll of tools, a water bottle, cold beef, chocolate and soup powder. “It seems probable that [he] tried to climb too quickly, and then tried to turn with the tail down. The result would inevitably be a side-slip and dive. This type of Bleriot, if there is room below, can always be brought back from practically any position, but under the circumstances of the accident something like 300 feet would be needed to recover, whereas the evidence says that the fatal turn commenced at about 200 feet.”

Robin Skene and Raymond Barlow were the first RFC casualties of World War One. Skene is buried at Send (St Mary’s) Churchyard in Surrey; Barlow is buried in Grave 1.4.9 in Bulford Church Cemetery, Wiltshire.

The first fatalities from enemy action

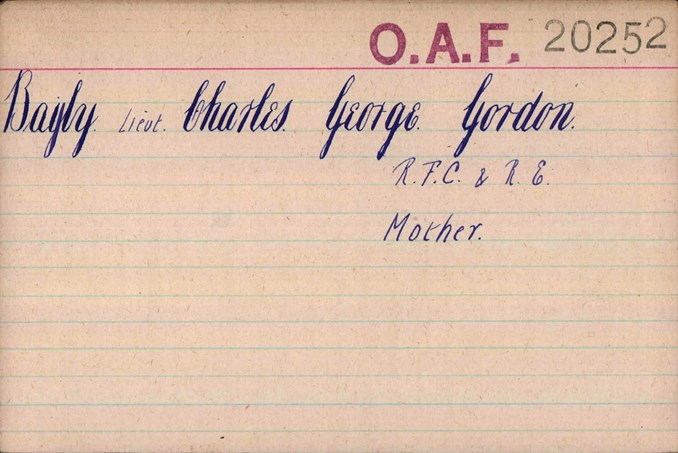

Royal Engineer Lieutenant Charles George Gordon Bayly, great-nephew of Gordon of Khartoum, after whom he was named, trained as a pilot in 1912 and earned Aero Club Certificate 441. In May 1914, as the storm clouds of war gathered far beyond the Wiltshire horizon, he polished his aviation skills at the Central Flying School (CFS), Upavon and talked of telegraphy and strut-wire tension in the mock Tudor-style officers' mess.

On 4 August Britain declared war on Germany. Lieutenant Bayly joined 5 Squadron Royal Flying Corps. He had only a week to prepare for his flight to France on 12 August. Young pilots were eager to prove themselves, although their precise wartime role was unclear; most important was to get into the fight before it was finished.

Bayly flew his machine from Dover to Amiens in France, and then onwards to Maubeuge, a key fortified town and railway centre near the Belgian border, hard by Marlborough's old battlefield of Malplaquet. This was no sudden choice: eight years before, British and French military staff had agreed Maubeuge as assembly point for an Expeditionary Force of 100,000 British troops to combat any invasion of neutral Belgium. The RFC swiftly mobilised some 860 officers and men at Maubeuge with all twenty of its remaining planes – two had crashed en route - but was already frantically improvising with its manpower and machines.

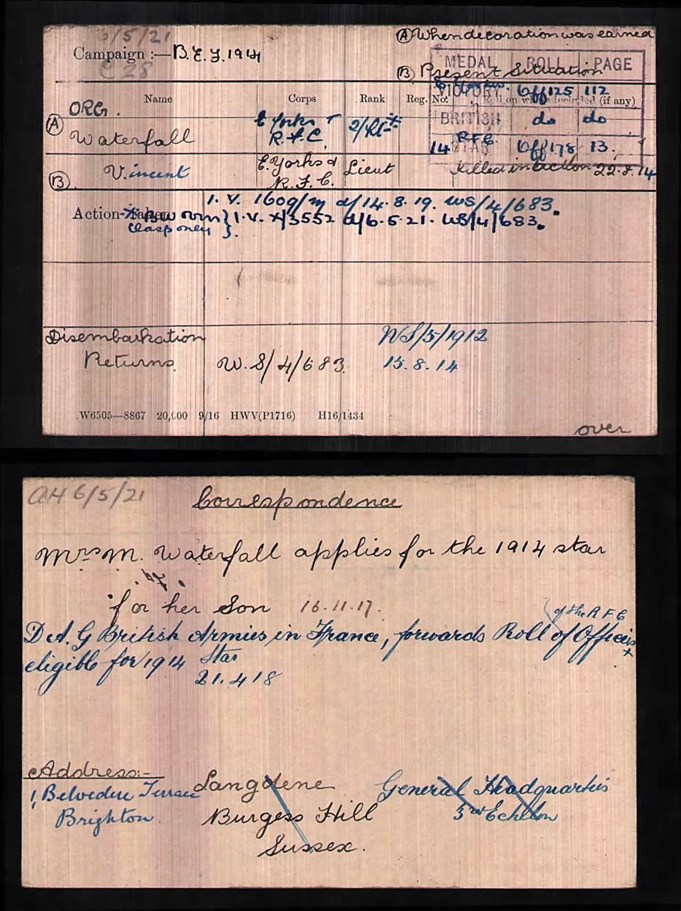

As British land forces hurried across France, civilians reported German troops in large numbers advancing through Brussels south-west towards Mons, 30 miles away. The RFC was tasked to confirm rumour by observation. At 10:16 am on 22 August, Lieutenant Bayly took off in Avro 504 No 390 flying as observer with pilot Second Lieutenant Vincent Waterfall - the rule that two pilots must not fly together had already been overridden by the need for qualified observers.

Vincent Waterfall was born in Grimsby on 25 May 1891. He was commissioned in the 3rd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, on 27 January 1912 after service as a Corporal in the Brighton College Contingent, Officers’ Training Corps. He trained as a pilot at the Vickers School in 1913 and gained RAeC Certificate No 461 on 22 April 1914. The pages of Flight for 1913 and 1914 trace his flying career, as he evolved from doing simple straight flights and circuits to more complex manoeuvres. In many ways, his progress was very similar to that of Gordon Bayly, and can be regarded as typical of the education of a pre-War pilot. By April 1914 he was described as being ‘thoroughly at home on the new Martinsyde monoplane” and went on to become the Martinsyde Company’s pilot. He left Martinsyde to join the RFC in June 1914, and was replaced at the company by Robin Skene (see above). There is a note in the 31 July edition of Flight about Mr Waterfall flying from Farnborough to Brooklands as passenger in a Vickers ‘Gun Bus’ flown by Mr F Barnwell.

To the observer fell the duty of defence. At best, he would have carried a carbine, shotgun or Colt Browning revolver, or made do with a flare pistol; the first Lewis gun would not be mounted on an Avro until October. Tales abound of this new airborne fraternity saluting each other with courteous waves, before graduating to vigorous shaking of the fist, lobbing of bricks and then small arms fire. But, at this early stage of the war, armed only with a keen pair of eyes, Bayly's hands gripped his binoculars as firmly as they had a rugby ball at the put-in. Most missions were flown not for bombing or combat but for reconnaissance and artillery observation; aerial dogfights captured the public imagination but the reality of wartime aviation was far more pragmatic.

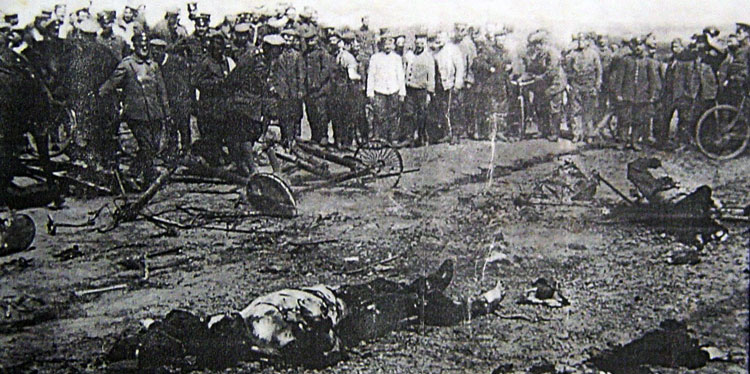

In August, however, the threat was not yet in the air but from the ground. Flying at 2,000 feet, Avro 390 flew over the Enghien-Soignies area at around 10.50, making a pass at just 20 metres or so, the Germans so surprised that they failed to fire a single shot at an easy target flying low and slow. The plane banked and returned towards one of the columns; the reception was ready this time. The Avro crashed by the roadside.

At a time when untrained anti-aircraft fire was more beginners' luck than judgment, the gunners must have been dumbfounded. The excited infantry of the 12th Grenadiers were quick to claim the kill. Their Captain, novelist Walter Bloem, wrote:

Suddenly a plane flew over us... I ordered the two groups to fire at it... the plane started a half-turn... but it was too late: it went into a dive, spun around several times then fell like a stone about a mile from here.

Bayly and Waterfall had no choice but to go down with their ship. Parachutes were not worn: the Air Board saw them as un-British, likely to undermine the crew's fighting spirit and desire to stay with their machine, 'which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair'. They died on impact in a mess of splintered wood and propeller blades. Little wreckage was left after burning fuel incinerated the doped canvas and ash frame. Unsure what to do with their first dead foe - the fallen fliers they called 'Black Angels'- the soldiers doffed their caps, fired in salute over the smoking wreckage and hastily covered them with four inches of soil. Local Belgians placed flowers for those who had flown to rescue them from invasion. The local landowner later exhumed the corpses and placed them in zinc coffins, hidden in his distillery cellar to await a decent burial. For the German commander, Von Kluck, the wrecked Avro and bodies in RFC flying tunics gave the first proof that British Expeditionary Forces were on the continent of Europe.

Bayly's reconnaissance report, unfinished and fatally interrupted, was found by Belgian peasants. His last words, scrawled at 11.00hrs, note: 'cavalry, 4 columns infantry, other group of horses and column turning left to Silly'. By the time this reached Command HQ it was of no practical use: the war had moved swiftly on, the retreat from Mons was in full flight.

Bayly and Waterfall can claim the doubtful honour of flying in the first British aeroplane to be shot down by enemy fire. Both airmen are now buried in Tournai Communal Cemetery, Belgium; Lt C G G Bayly in Grave III.G.3 and 2Lt V Waterfall is next to him in Grave III.G.4. Both men were 23 when their lives ended so abruptly.

The above article is based, in part, on Gareth Morgan's original article 'The First To Fall'.