"And Bert’s gone syphilitic" – The Real Tragedies Behind the Cane Hill Hospital Memorial at Croydon.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- "And Bert’s gone syphilitic" – The Real Tragedies Behind the Cane Hill Hospital Memorial at Croydon.

In 1981 nearly 6,000 bodies were exhumed from the cemetery of Cane Hill Hospital, formerly the 3rd Surrey County Lunatic Asylum. They were cremated and their ashes scattered at Croydon (Mitcham Road) Cemetery. In 2009 a considerable correspondence took place on the Great War Forum, members investing time and effort in putting forward the cases of serviceman of the Great War who had been identified amongst them to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, who subsequently added the details of 18 individuals to their database. They were commemorated on a memorial, later stolen. In 2016 a further memorial with 18 names of Army veterans was erected, with the names of eight others, Army and Navy, on adjacent plaques, not recognised by the CWGC.

Above: The Cane Hill Memorial at Croydon Cemetery

Assuming trauma

The Sutton & Croydon Guardian, covering the unveiling, wrote that ‘soldiers admitted to the asylum suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, then known as shellshock’. A representative of the British Legion, who had dedicated two years to the erection of the memorial stated: ‘These are soldiers that suffered invisible injuries, like post-traumatic stress or brain damage’. A lieutenant-colonel of the Coldstream Guards, delivering the eulogy at the remembrance service, spoke of ‘the poor souls who broke down mentally and were classed as mad, because of the constant strain and horrors they faced’.

These comments contain a single assumption. The concept of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (2) having passed into everyday use, the presupposition was that these soldiers were likely victims thereof. This modern preoccupation with trauma creates a distorting prism through which we view the experiences of soldier of the First World War soldier – as John Bourne and Bob Bushaway have noted: ‘It is a modern conceit that soldiers must necessarily be traumatised by war’. (3) There are indeed a multiplicity of tragedies behind this memorial. It is only when we look at the Cane Hill men as a group, however, that the true nature of the overarching tragedy becomes clear.

Above: Cane Hill Hospital, Coulsdon, Surrey - now a housing estate

The illnesses

It will come as no surprise that the word ‘shellshock’ does not appear in the 18 pension records traceable of those on the memorial (including one from the two additional plaques). In 1917 the General Staff decreed: ‘In no circumstances whatever will the expression "shell-shock" be made use of verbally or be recorded in any regimental or other casualty report, or in any hospital or other medical document except in cases so classified by the order of the officer commanding the special hospital for such cases.’ (4) Instead, out of 16 given diagnoses, we have seven of ‘General Paralysis of the Insane’ (GPI), two of ‘Dementia Praecox’, two of ‘delusional insanity’ and one of ‘mania’, with two of ‘melancholia’. One soldier was discharged suffering from ‘idiocy’, and another as an ‘insane epileptic’.

The curse of syphilis

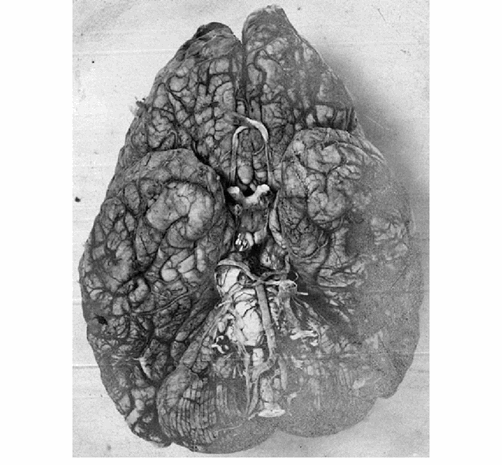

As Siegfried Sassoon foreshadowed in ‘They’, over a third are cases of GPI, a possible outcome of tertiary syphilis (the last stage of an untreated infection. Current estimates are that 15-30 per cent of untreated infections will proceed to what is now known as neurosyphilis). That cases of GPI should figure so highly amongst these deaths is unsurprising in that it was a terminal condition resulting from neurological degeneration. Twenty per cent of male asylum admissions during the period were cases of GPI. (5) Indeed, at Cane Hill itself in 1913, the figure was 23 per cent. (6) Syphilis was a true plague of the Victorian era. The Royal Commission on Venereal Diseases reported in 1916 an overall prevalence in the population of 7.8 per cent, and gave opinion that the rate ‘cannot fall below 10 per cent of the whole population in the large cities’. Syphilis formed roughly a quarter of the 400,000 venereal infections in the British forces during the war; (7) the Canadians estimating a prevalence of 4.5 per cent in their troops. (8) It was a common but incurable disease of the age.

GPI emerges between 10 to 30 years after infection, and from diagnosis to death is a period of three to five miserable years. None of these men therefore contracted syphilis during the war itself. Two of the seven were Regulars, five attested during the war. All were married, raising the sad possibility of infection of their wives and children. The symptoms of one as given in his discharge documents give the flavour of the neurological symptomatology: ‘Dull & demented … rather restless … little to say for himself … marked ataxia … pupils very sluggish … slurred speech’. Seven and a half months later this individual was dead. Delusions (a poor sign) were present in another: ‘States he was at Mons & was wounded & gives a vivid account of his experiences on active service. He has not been on active service’. Indeed, four of the six had not seen active service. In five cases the illness was (almost certainly correctly, given its nature) seen as not ‘aggravated’ by war service. The other two cases have no distinguishing features that might indicate why a conclusion of ‘aggravated’ was reached (although both had been on the Western Front), and likely simply indicates the lack of an accepted view about GPI amongst the medical staff. Cases in hospitals declined rapidly in the 1920s as partially effective treatments for syphilis, arsenical Salvarsan 606 (from 1910) and deliberate malarial infection (from 1917), evolved.

Above: Diseased brain of a GPI patient (Creative Commons licence)

Psychosis

Two were cases of ‘dementia praecox’, the old term for schizophrenia. This condition will emerge in up to 0.7 per cent of the population between the late teens and early 30s (the two cases were 24 and 29), with symptoms of hallucinations, delusions, disorganised thinking, withdrawal, decreased emotional expression and apathy. Whilst probably about a fifth of asylum admissions in the early part of the 20th century were such cases, British psychiatrists were slow to accept the concept, and patients were often given other diagnoses. The nature of the delusions and hallucinations are illustrated in one soldier: ‘He imagined that the men in his regiment poisoned his food … has heard voices telling him he is to be made away with because he is a spy’. The case was viewed as ‘not aggravated’ by military service (the individual was in a works battalion). In the other case, the soldier had received a leg wound and the symptoms emerged immediately after discharge from hospital and at home, attacking his mother, ‘persistently knock(ing) his head on the floor … restless, incoherent and very unstable’. The conclusion was reached of ‘epileptic and insane hereditary’, the ‘exciting cause’ being service and wounding. This last comment – ‘hereditary’ – is notable, for in 1910 at the Cardiff Mental Hospital a hereditary condition was identified in 39 per cent of cases. (9) Modern science sees schizophrenia as ‘neurodevelopmental’, resulting from interaction between genes and environment, of which latter psychosocial stress would be one aspect.

There were two cases of ‘delusional insanity’. In 1910, such cases made up 20 per cent of those admitted to the Cardiff Mental Hospital and 21 per cent of the admissions to the Hereford Lunatic Asylum. One of these two individuals claimed people were ‘accusing him of being a spy’ and that he had been ‘tortured by Germans in the night’. His condition was seen as ‘attributable to service’ and ‘not constitutional’. The other reported being ‘chased by colonial troops at night’, and ‘produced his watch saying “this is my face”’. Whilst it was noted ‘has not been under fire’, his condition was again deemed ‘attributable to ordinary military service’. Whilst the delusions were coloured by the wartime environment (which no doubt gave rise to the ‘attributable’ view), these persistent psychoses were serious mental illnesses, and almost certainly constitutional in the view of modern knowledge. In present-day psychiatry, paranoia and paranoid schizophrenia are distinguished by the number of other symptoms in addition to the core delusions – we cannot tell which condition these men suffered. Those afflicted would remain without effective treatment until the arrival of chlorpromazine in the 1950s.

There was one case of ‘mania’, not regarded as caused or aggravated by military service (the individual saw six weeks service on Western Front as infantry), and was likely what would now be considered bipolar disorder. One poor serviceman was diagnosed with ‘idiocy’, i.e. a learning disability (and who had seen home service only), and another as a ‘possibly insane epileptic’ (home service only), whose fits increased in the army, likely causing further brain damage.

Finally there were the two cases of melancholia. One case was invalided from Salonika with ‘malaria and melancholia’ (malaria being now known to be linked to depression). The other had only seen home service and his case was seen as not the result of but ‘aggravated by’ military service. Melancholia, forming 20 percent of 1910 Cardiff admissions and 12 per cent of Hereford admissions, indicates a particularly marked form of depression, later described as ‘endogenous depression’, and viewed as biologically determined.

Psychological casualties of the BEF

From about five and a half million British soldiers who served, a total 80,000 cases of ‘nervous disorders’ was finally arrived at in Diseases of The War. (10) Peter Leese suggests, based on studies of the French and German armies that a more reliable overall figure is around 200,000. (11)

Predictably, however, given the preoccupations noted earlier, such estimates have been amplified. Jay Winter, pushing the boundary of Second World War combat stress estimates, (12) plucks from the air a figure of 20 per cent of all Great War casualties being psychiatric in nature, suggesting ‘a band of probability’ with its lower end at 4 per cent of all casualties and at its upper end at 40 per cent. (13) This does no justice to the men who served. Based on Leese’s review, the figure is in fact just under nine per cent of all casualties. If this is correct, the fact is that there were relatively few formal psychiatric casualties, rather than so many. Alex Watson observes that ‘most men clearly overcame battle stress extremely successfully’, (14) and this writer has suggested that soldier’s coping mechanisms, born of attitudes of the age, were strong and effective. (15)

Cases of ‘nervous disorder’ do not equate to combat stress, however. Diseases of The War, in describing 28,533 ‘shell shock’ casualties to the end of 1917, includes a set of statistics for the Gallipoli campaign for hospital admissions for ‘disease of the nervous system’. Forty-five per cent were combat stress cases, 12 per cent were cases of epilepsy, 23 per cent were ‘other diseases of the nervous system’, and 4 per cent ‘mental diseases’, these latter categories covering the conditions of the Cane Hill men. Further, a study of nervous disorders in the Salonika army relates a ‘previous personal history of neurosis’ in over 80 per cent. (16) What these figures point to is that ‘combat stress’ formed only half the picture of psychiatric disorder, and that well over half were vulnerable by virtue of past psychiatric history. Peter Barham draws our attention to the number of post-war permanently hospitalised servicemen who had pre-war histories of significant mental illness that went without enquiry at a cursory medical examination preoccupied with their physical health.

Above: Asylum ward, 1920 (Courtesy BerkshireLive)

The tragedy of the Cane Hill men

The Cane Hill men are clearly not cases of ‘shellshock’. They all had serious psychiatric illnesses, now understood to be genetically influenced or biologically determined (e.g. GPI), whose emergence would have been likely inevitable. They were amongst the constitutionally vulnerable. It is quite possible that the cases of GPI may have been completely hidden until their neurological symptoms emerged, as they were bound to. The other cases, too, may well have been asymptomatic at enlistment. And if they were not, any oddity in their personalities would likely have been contained at home or in familiar workplaces and not initially evident. The fact that a proportion were retained on home service or spent little time at the front indicates that behavioural oddity was soon spotted. But what of environmental influence on the appearance of their illnesses? It may have been the simple transition to a very different (army) environment, disrupting previous coping, that was the psychosocial stressor, rather that combat – in only one case can we see wounding as the possible trigger for the emergence of a hereditary condition.

The fact that the Cane Hill men are not cases of PTSD is no less tragic. If they were victims of anything, it was less of war, and more of living in an era where a limited medical/psychological science was not harnessed to military selection, (17) and where there was no effective treatment of serious psychiatric illness. This is the true tragedy behind the Cane Hill Memorial, seen without the spectacles of 21st century preoccupations and assumptions.

Peter Hodgkinson is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist and author of Glum Heroes: Hardship, Fear and Death – Resilience and Coping in the British Army on the Western Front 1914-1918, published by Helion in 2016.

Footnotes

- Siegfried Sassoon, ‘They’, Collected Poems 1908-1956, (Faber and Faber, 1984).

- The concept of PTSD first appeared in 1980, wrought out of the experiences of Vietnam veterans in particular.

- G.R. Husbands, Joffrey’s War, (Beeston: Salient Books, 2011, p.20.

- General Routine Order No. 2384, 7 June 1917.

- Gayle Davis, The Cruel Madness of Love, (Clio Medica, 2008).

- W. D. Nicol, ‘The Relation of Syphilis to Mental Disorder’, Br. J. Vener. Dis. (1933).

- W.G. MacPherson, W.P Herringham, T.R Elliott, and A. Balfour, Medical Diseases of the War, Vol II, (HMSO, 1923) p.118.

- A. McPhail, The Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War: The Medical Services, (King’s Printer: Ottawa, 1925).

- Asylum Reports, The Lancet, (25 November 1911).

- MacPherson et. al. op. cit. pp.7 & 56.

- P. Leese, Shell Shock, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), p.10.

- The War Office retrospectively estimated that between 5 and 30 percent of all sick and wounded during the Second World War were psychiatric casualties, this figure largely depending on the type of warfare fought. (E. Jones & S. Wessely, ‘Psychiatric Battle Casualties’, British Journal of Psychiatry, 2001, p.243).

- J. Winter, ‘Shell Shock’, in J. Winter (ed.), Cambridge History of the First World War, Vol 3, (Cambridge: University Press, 2016), p.332.

- A. Watson, ‘Self-deception and Survival’, Journal of Contemporary History, (2006), p.248.

- P. Hodgkinson, Glum Heroes, (Solihull: Helion, 2016).

- Macpherson et. al., op. cit. p.5.

- P. Barham, Forgotten Lunatics of the Great War, (London: Yale University Press, 2004).

- This would only occur during the Second World War.