British Prisoner of War Deaths: a case study from one PoW camp

- Home

- World War I Articles

- British Prisoner of War Deaths: a case study from one PoW camp

Lidzbark Warminski, previously known as Heilsberg, is a town in northern Poland. In 1918, the area was part of East Prussia and was the location of one German's most easterly prisoner of war camps. The Heilsberg camp contained mainly Russian and Rumanian prisoners, with British and Commonwealth POWs only a small proportion of the camp population.

It is believed that in October 1918, there were about 1,000 British POWs at the camp at its satellite or sub-camps, out of a total of 95,000 prisoners.

Above Map: prisoner of war camps in Germany 1914-18. Heilsberg is the second most easterly of the camps; see extreme right of map (courtesy Wikipedia)

The vast majority of prisoners were Russian, a small proportion were British. Towards the end of the war, 39 of these British prisoners fell victim to the insanitary conditions and died of disease, probably exacerbated by the poor and insufficient rations that they were receiving. They were buried at the time at a cemetery but because these graves were un-maintainable, for nearly a hundred years the 39 servicemen were commemorated at Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery some 70 miles west of Lidzbark Warminski. However some years ago, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission took the decision to mark these 39 men at a new cemetery on the site of the PoW camp. At the end of this article is a link to another article detailing the story of the new cemetery. There is also downloadable PDF, listing of the men and where they came from. It is hoped that, over time, a number of the relatives of these men will come forward.

Although only five service records still exist of these 39 men (most of the records probably fell victim to the destruction of the warehouse in which the records were stored in London in the Second World War) we can, via the WFA's Pension Records, learn a fair amount about these men.

As a result of the Pension Record Cards, probably for the first time ever, it is possible to analyse the causes of death of a sample group of Prisoners of War. The nineteen pension cards that give a cause of death are listed below:

Causes of Death

Henry Appleby - General Exhaustion

Frank Bower - Pneumonia

George Buck - Colitis

William Embleton - General Exhaustion and Colitis

Frederick Foot - Died of "disease"

Firth Garlick - Pleurisy

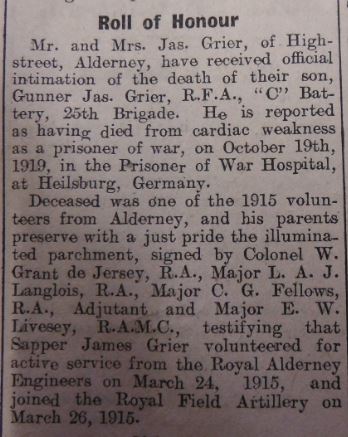

James Grier - Cardiac Weakness

Harold Harlow - "Sickness"

Arthur Hobson - Cardiac Weakness

Thomas Jewell - Pneumonia

William Jobson - Died from "disease"

William Gordon Jones - Bronchial Catarrh and Cardiac Weakness

Edward Kearns - Cardiac Weakness

Thomas Lock - Cardiac Weakness

Charles Ramsden - Brain disease

Charles Ryder - Pneumonia

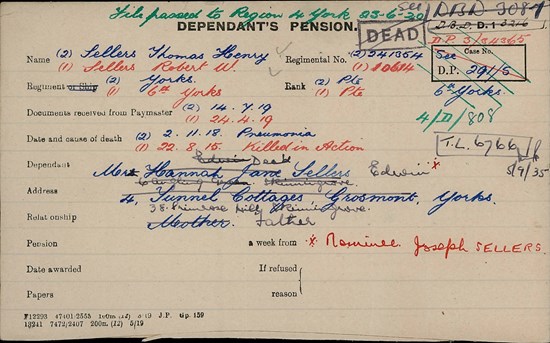

Thomas Sellers - Pneumonia

Edward Walker - Colitis

Walter Whysall - Pneumonia

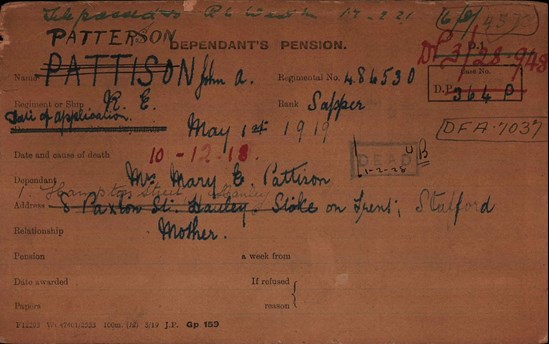

Above - the card for Patterson (which does not show a cause of death)

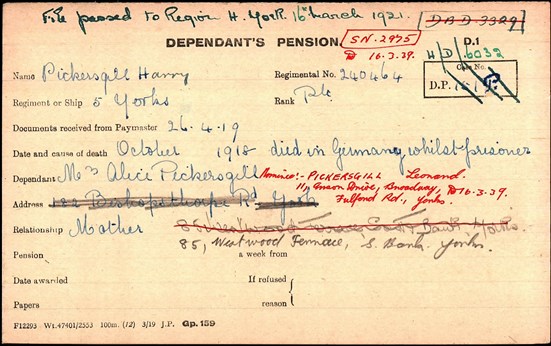

Above: the card for Harry Pickersgill who 'died in Germany whilst prisoner'

Above: the card for Sellers, which does detail his cause of death.

There is no cause of death noted on the cards of the following 20 men:

Alexander Anderson

John Armstrong

Seymour Blewitt

Fred Carter

Albert Cockin

Ernest Edwards

John Gillyon

William Hugh

William David Jones

Arthur Lane

Henry Lochtie

John Partridge

John Patterson

Harry Pickersgill

Morton Posstlethwaite

Bertie Pottinger

Joseph Shall

Charles Sharp

Alfred Warner (no card can be located)

William Williams

Virtually all cards have been located for the 39 men named in this article. Only one has not been traced. These are shown on the pdf below:

Download PDFNOTE: The digital copies of Pension Cards and Ledgers are available and are freely accessible by members of the Association via the link here: WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION PENSION RECORDS

A further analysis of the battalions these 39 men served in suggests that no less than 20 served in units of the 50th (Northumbrian) Division when they were captured. From the information we have on some of the men, we can speculate that most were taken prisoner in 1918 during the German spring offensives.

50th (Northumbrian) Division in 1918

It could be said that the 50th (Northumbrian) Division was very unlucky to be in the path of three of the German attacks between March and May 1918. The first of these, the German 'Michael' offensive, opened on 21 March. After successfully helping to stem the tide of the German advance, the division was sent north to a quiet part of the line where it soon found itself in the path of a second German offensive on 9 April.

Frank Bower (above) from Dewsbury was captured in April 1918 during the Battle of the Lys. He had not even fired a shot at the Germans - he was a newly arrived reinforcement and was in hospital with a stomach ailment when the Germans took him prisoner.

Again the British were successful in halting the Germans, but a number of divisions, including the 50th, were now exhausted and they were sent to a quiet part of the line, well to the south, where no attack was expected.

The Chemin Des Dames

The 50th Division was sent to the Chemin des Dames sector, where the French were holding the line. All was peaceful.

"The woods were full of violets, lilies of the valley and flowers of all kinds...the artillery units, back from the front line trenches had 'the most perfect observation posts they had ever seen, and the walk to them through the wood was delightful...' 'This is the place we have long been seeking'."

(The Fiftieth Division 1914-1919; Everard Wyrall)

The calm was shattered on the night of the 26/27 May when the Germans opened a truly massive artillery bombardment. Initially this was aimed at the British rear areas, with the intention of knocking out headquarters, communications and artillery units.

The two artillery brigades of the 50th Division (250 Brigade and 251 Brigade) were badly hit in this bombardment. The divisional history records the following about the losses to the artillery:

"No guns were ... saved."

Such is a portion of the Divisional Narrative which tells of the misfortunes of the 250th and 251st Brigades, RFA, under the commands respectively of Lieut-Colonel FGO Johnson and Lieut-Colonel FR Moss-Blundell. On the right, the 250th Brigade kept their guns in action longer than the 251st Brigade, for the latter was quickly enveloped from the left. The narrative contained in the war diary of the former brigade is interesting as showing the battle from the gunners' point of view:

At 1 a.m. the enemy bombardment commenced. All lines went down within five minutes. Bombardment was very heavy on all forward areas and on battery positions and head-quarters. S.O.S. went up about 4 a.m.

No information was received about the positions of the infantry or state of batteries; orderlies sent out were almost invariably missing. News received about 4.30 am from C/250 through an infantry officer attached to them. At 3 a.m., when he left, only one gun was in action, remainder having been hit. About 6.30 a.m. Major Shiel and Lieut. Richardson arrived at headquarters and say that A/250 had removed sights and breach mechanism as the creeping barrage has passed them, and the enemy are about eight hundred yards in front of them.

Image (copyright IWM, Q55010): German infantry working forward through the village of Pont Arcy, taken from the British IX Corps on 27 May 1918.

Wyrall, in the Divisional History continues:

Second-Lieut Hopwood had reported from B/250 that they were still fighting with three of the four guns on their main position. A message had also been received that D/250 were continuing to fire. No further news received from C/250. From information received later, personnel from B/250's main position nearly all got away when the enemy arrived on the position. Very few got away from detached section of B, but fair number from detached section of A/250. Very few got away from D/250. Capt. Darling was last seen going towards the enemy with his revolver and Lieut. Earle and remaining gunners were firing the last gun left in action. No one got away from main position of C/250, but most of the detachments got away from detached section where Second-Lieut Costar was last seen going towards the enemy with his revolver.

James Grier, from Alderney, on the Channel Islands was one of the men of 'C' Battery of 251 Brigade, Royal Field Artillery. He had volunteered in 1915 and seen much action during his three years of service. Captured with him, and also from 251 Brigade, RFA, was Edward Kearns from Hull. In 250 Brigade was Henry Lochtie from Edinburgh.

Image: James Grier - courtesy of Steve Mannion

Image: a roll of honour entry in the Guernsey Evening Press for 22 February 1919 announced Gunner Grier's death. The article contains two errors: he was in the 251st Brigade, not 25th; and he died in October 1918, not 1919. Courtesy Priaulx Library, Guernsey/BBC.

Meanwhile, the infantry was faring even no better. In the 6th Durham Light Infantry was William Jones from Llanfyllin, Montgomeryshire. He attested into the army in January 1917 and was called up just eight days after his 18th birthday in November 1917; he described himself as a "student", although elsewhere he is described as a "munitions worker". He is recorded as being 5' 10" tall, and weighing just short of 11 stones with brown hair and grey eyes. After undergoing nearly five months training he arrived in France at the end of March 1918 and, after a short period of further training in France, he joined his battalion on 20 April.

Image - William Jones, courtesy the Jones family/PA

Image: War Memorial at Llanfyllin, the home town of William Jones

William's battalion took very heavy casualties, with at least 80 men killed during the attack on 27 May, and the subsequent days of withdrawal. Sometime during this frantic fighting, William Jones was captured.

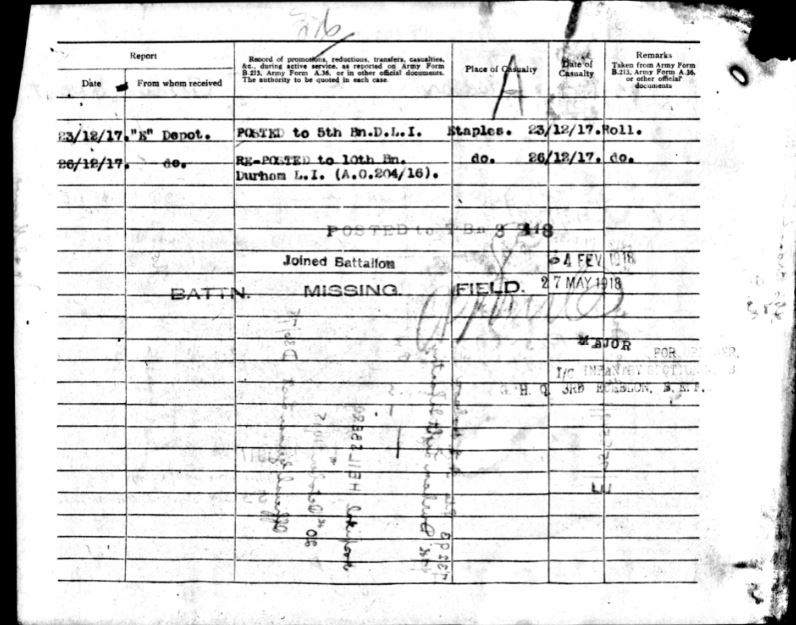

Arthur Hobson, of the 7th DLI was also captured at this time, as shown from his service record.

Above image reproduced courtesy of and © The National Archives, London, England

Grier, Kearns, Lochtie, Jones and Hobson all ended up at the PoW camp at Heilsberg.

Prisoner of War Camp, Heilsberg

The conditions in the camp were dreadful. Disease was rife and the men had little to eat (the British naval blockade was starving Germany - they had insufficient rations for their own population, and few of these rations went to prisoners of war).

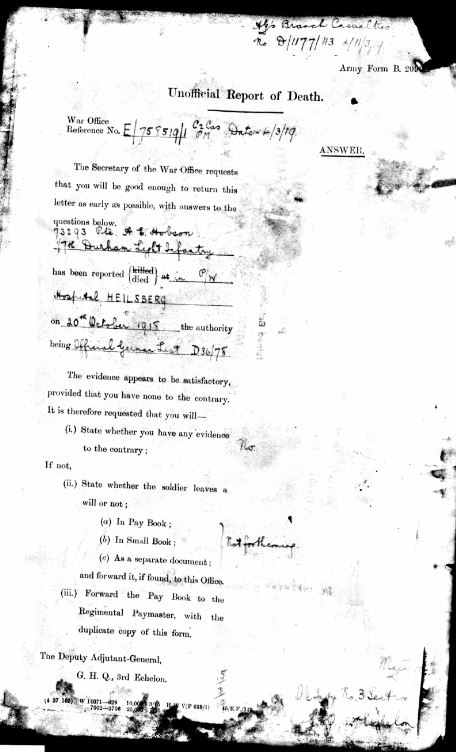

On 1 August, the first of the British PoWs at Heilsberg died. Frederick Foot of the RMLI, whose wife lived at Newtown, Charlton Marshall, Blandford, Dorset died "of disease". Over half of the men now commemorated on the site succumbed in October. Twenty one of the men passed away in this month, including Arthur Hobson, as detailed below on the "unofficial notification of death" held in his Service Record file.

Above image reproduced courtesy of and © The National Archives, London, England

Other deaths?

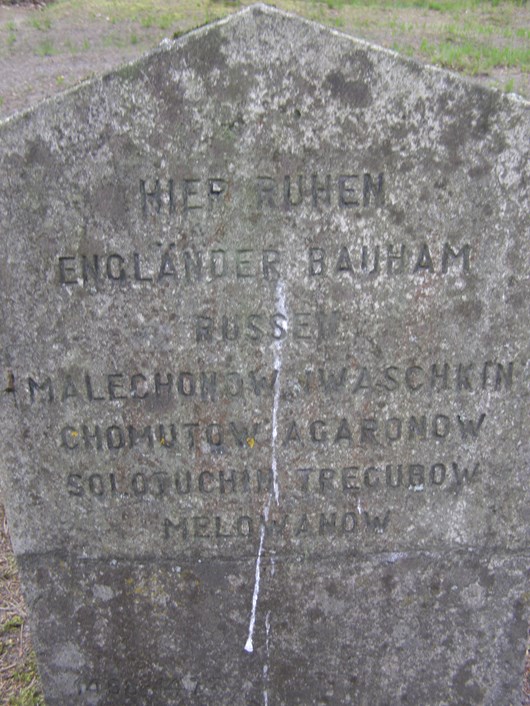

Evidence has come to light that there may, in fact, be other (unidentified) British soldiers buried among the large number of graves at Lidzbark Warminski, as evidenced by these photos below:

Englanders "Goodall" and Englander "Bauham"

If the name on the above headstone is accurate, and if it represents a British soldier called GOODALL who died as a prisoner of war, then the number of men this could be is limited. Assuming GOODALL died in 1918 (which is not certain, but is not unreasonable, there are three possibilities:

1) L/Cpl Harry Goodall (546050) of the 509th Field Company, RE who died on 21 March 1918 and is commemorated on the Arras Memorial. There are problems with this hypothesis given the soldier here died in East Prussia

2) 2/Lt Harry Armitage Goodall of the RFA, attached to the 16th TMB. He died on 22 March 1918 and is commemorated on the Pozieres Memorial. Again, the date of death and location of the above headstone cause problems.

3) Private William Goodall of the 4th Gordon Highlanders. William died on 13 April 1918 and is commemorated on the Loos Memorial. The same issues of his date of death and the burial in East Prussia again occur.

'Bauham' is almost certainly an error. If we consider the letter 'u' to be in error, there are numerous possible surnames to explore. One of these is Private E G Barham. This soldier, (126913, Royal Engineers) however, has a known grave at Niederzwehren Cemetery, Kassel, in Germany.

(Images - courtesy Trev Hill)

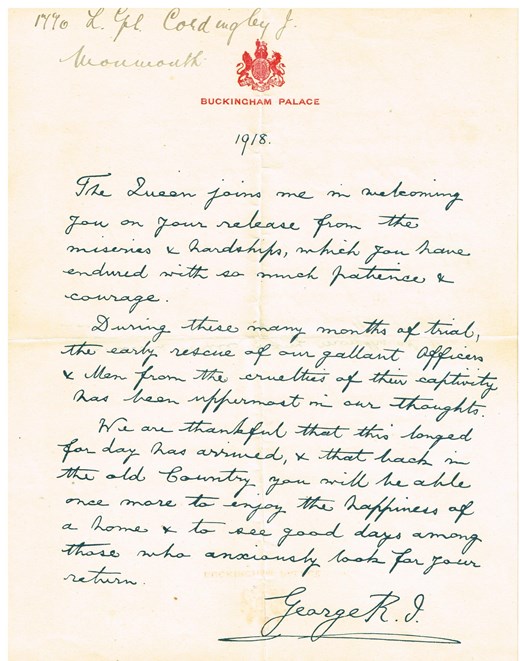

Survivors of the PoW experience

Of course, most men who were captured did eventually return home, and it seems they received a scroll to mark their time as Prisoners of War. One example of this is shown below

Above: A hand written Letter of recognition from King George V 1918 sent to Lance Corporal James Cordingley; facsimile mass-produced by lithography and individually addressed (source: Wikipedia)

Dedication of New Cemetery

The new Lidzbark Waminski British Cemetery was formally dedicated on Friday, 16 May 2014, in the presence of the British Ambassador, the Vice President of the CWGC, and Polish veterans of the Second World War. A troop of Polish soldiers fired volleys over the graves and Polish schoolchildren and scouts layed grave candles. The WFA was represented by Trev Hill, who laid a wreath on behalf of the association.

A full article about this new cemetery and how it came to be built so long after the end of the war is detailed here:

The Heilsberg 39: A New British First World War Cemetery in Poland

Further reading

Sidney Rogerson: The Last of the Ebb

If anyone has any further information about any of the men commemorated at Lidbark Warminski, please contact the author of this article.

Article courtesy and (c) David Tattersfield, 2014. Image copyright with respective authors.

Below - a downloadable table of the 39 men - this (when downloaded) can be 'zoomed' to make the text larger

Download PDF