From the Suvla Plain to Victory: William Ralph Peel

- Home

- World War I Articles

- From the Suvla Plain to Victory: William Ralph Peel

On the 16 November 1918, Lt Col William Ralph Peel and the men in his 10/Manchester Regiment were lined up smartly in the main square of a sprawling village on the outskirts of Maubeuge. Its population, only days earlier, had finally been relieved from a German occupation that had begun over four years previously in August 1914.

The purpose of this post armistice parade was to receive the admiration and gratitude from the Mayor of Hautmont, who, in his speech pronounced Lt Colonel Peel and his men as Hautmont’s friends, liberators and avengers.[1]

Above: Lt Col William Ralph Peel (centre), alongside the Mayor of Hautmont 16 November 1918

In return for these heartfelt words and a bouquet of flowers, two field guns, hastily left by the Germans as they withdrew, were presented by the battalion as a gift to the townsfolk. In his own speech, (impressively given in French),Colonel Peel reminded the onlooking citizens:

I have the great honour, on behalf of the officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the 42nd Division of the British army, to offer you these two pieces of canon, which my battalion, the tenth of the Manchester regiment, took on November 8th when we had the honour of liberating this city from the yoke of barbarians. It was four years ago that a battalion of the same regiment had the opportunity, at the retreat of Mons, to pass through the town of Hautmont, and now God wanted it to be our-selves who were the first English to enter, but under what differing circumstances.[2]

Concluding the formalities, the mayor graciously accepted the guns and summed up eloquently:

The reign of barbarism is doubtless over. Prussian militarism has lived its last; the voice of cannon has given way to the voice of law. Thanks be given to the Allied Powers and to the patriotism of the Anglo-French people in delivering our region. The victory smiled on their common efforts, the beneficent and restorative peace reserves for us, happy days. The sight of these pieces of cannon, perpetually silent, will we hope, not be less eloquent for our fellow citizens, it will remind them of the critical hours of their existence, as well as your precious help. To you, our allies, you have become our friends and our hearts beat in unison.[3]

William Ralph Peel was not in the Army as the 2/Manchester Regiment trudged wearily through Hautmont on the retreat from Mons. His war was to start in earnest on 19 September 1914 when he obtained a commission into the Yorkshire Regiment, (Alexandria, Princess of Wales Own). At 27, he was engaged as a ‘Land Agent’ residing at the family home ‘Knowlmere Manor’ near Clitheroe. This imposing house had been the family seat for generations and was more recently seen in the 1980’s TV adaptation of Sherlock Holmes ‘The Silver Blaze’.

The reality of war was, however, soon to bite for William when, on 24 October 1914, news reached him that his older brother had fallen at the First Battle of Ypres. Lawrence, a career soldier, had landed with the 7th Division earlier that month, disembarking with the 2/Yorkshire Regiment a battalion he had joined in 1905, he fell commanding the 7th Divisional Cyclist Company. Still missing by the armistice, he is commemorated on the Menin Gate.

France and Flanders would not be the destination for William however, by now Captain and Adjutant of the 6/Yorkshire’s, as part of 32nd Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division, July 1915 found the battalion at Witley Camp in Surrey. It was here that they were warned for the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. Destination, the Dardanelles.

Sailing on the SS Aquitania from Liverpool it was far from an uneventful journey:

...her escort of destroyers were soon having trouble keeping up, and began to lose touch with her, and so the ship had to rely on her speed to evade attention from German submarines which roamed the Mediterranean looking for easy and important targets. Despite the ships speed however, the SS Aquitania was attacked but fortunately the torpedoes missed, and the submarine was finally chased off by the escorting destroyers. During this attack on of the ship’s stewards collapsed and had to be taken to his quarters. It was later learnt that he had been on board the Cunard liner Lusitania when she had been torpedoed by the U-20 on 7 May 1915 with the loss of 1,198 men, women and children.[4]

When they safely arrived at Mudros Bay, Lemnos on the 10 July they transferred into bivouac positions at Imbros. Now within sight of the Gallipoli front, they were inspected by Sir Ian Hamilton on the 24 July.

William would not have to wait too long to see action, on the 6 August at 11pm, his battalion landed at Suvla ‘B’ Beach near to Nibrunesi Point. The battalion, under orders of the adjutant, wore a white patch sewn on the corner of their haversacks, two white armbands and triangular pieces of tin cut from biscuit boxes tied to the haversacks to act as unit identification.[5]

It was an opposed landing that the Official History states was the first to be made by any unit of the New Army, the attack being under conditions that would have tried the mettle of highly experienced troops.[6]

With A & B Company in the lead, the battalion proceeded to capture the dominating hill of Lala Baba. C Company landed shortly after under the command of Major Shannon and advanced on some pre-identified Turkish positions whilst D Company moved towards the Salt Lake shore and set up a piquet line back to the beach. Moving silently and swiftly with orders to use the bayonet only, the leading companies advanced to the peak of Lala Baba in total darkness. The Official History describes the assault as extremely hazardous, recording:

Officers and men fell thickly, most of the Turks scattered, but some lay low in their deep narrow trenches till the attacking troops had passed, and then sprung up to shoot them in the back. [7]

A further description came from Major Shannon he recalled in the Regimental History:

On arriving at the base of Lal Baba I ordered a charge, and we ran up the hill. About three quarters of the way up we came upon a Turkish trench, very narrow and flush with the ground. We ran over this, and the enemy fired into our rear, firing going on at this time from several directions. I shouted out that the Yorkshire Regiment was coming, in order to avoid running into our own people. We ran on and about twelve paces further on, as far as I can judge, came to another trench; this we also crossed and again were fired into from the rear. I ordered the company to jump back into the second trench, and we got into this, which was so narrow that it was quite impossible for one man to pass another, or even to walk up it unless he moved sideways: another difficulty was that if there were any wounded or dead men in the bottom of the trench, it was impossible to avoid treading on them in passing. There was a little communication trench running from right to left behind me, and whenever I shouted an order, a Turk, who appeared to be in this trench, fired at me from a distance of apparently five or ten yards. I had some difficulty in getting anybody to fire down the communication trench in order to quiet the enterprising Turk, who was endeavouring to pot me with great regularity, but eventually I got him shot’.[8]

The detailed account by Major Shannon is remarkably accurate in relation to the ground over a century on, the trenches still tracible among the scrub of Lal Baba, and indeed 12 paces apart. The battalion war diary later recorded, ‘enemy driven north-east to Hill 10. Casualties 16 officers and approximately 250 other ranks.’[9]

Above: Crossing the Turkish trenches where William Peel was wounded, Lala Baba 7 August 2015, 100 years on

Among those officers wounded was William Peel, when he returned to battalion on the 10 November, they were occupying the trench-line known as Green Lanenear to Jephson’s Post still in the Suvla sector. His war diary entries are concise but do mention the daily grind of being shelled and sniped through to their withdrawal in December 1915. He mentions the deterioration in the weather with heavy snow and ground frost throughout November, several the battalion being lost to frost bite.

At 10pm on 19 December 1915, William Peel along with Captain Earl, Lt Aherne and 102 other ranks left Gallipoli for the last time as the evacuation of Suvla Bay was completed.

In January 1916 he took temporary command of the battalion which by February was in Alexandria, Egypt. By July 1916 William and the 6/Yorkshire Regiment had been transferred to the Western Front.

Initially in the fairly quiet Arras sector, by early September they moved towards the Somme front line at Thiepval occupying dugouts at Crucifix Corner. Taking over trenches on the 9 September, they assaulted the German Wonder Work position and a nearby trench Turk Street five days later. Assisted by the battalion bombers working along the left flank, the battalion captured this position, consolidated and held off several counter attacks during the subsequent days until relieved on the 16 September, this action had cost the battalion 135 casualties, including their commanding officer Lt Colonel Cusack Grant Forsyth who was killed on the 14 September and today lies in Blighty Valley Cemetery.

Cusack Forsyth was a regular army officer who had been awarded a DSO as a young Lieutenant with the 2/Northumberland Fusiliers when seriously wounded at First Ypres. When he took command of the 6/Yorkshire Regiment in Egypt, (from the temporary command of William Peel), he was still under 30, his obituary in Malvern School Magazine commenting:

In his death the Army has lost one of its most brilliant and promising young officers, and I should think at the time he was given command of the Yorkshire Battalion he was probably the youngest commanding officer in the Regular Army. He had a great future in front of him if only he had been spared to come through this war.[10]

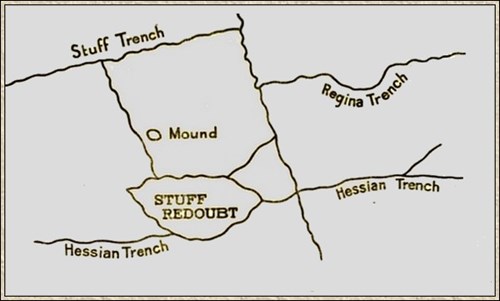

William Peel would see further action on the Somme just a few weeks later when the battalion hopped the bags once more, this time to attack Hessian Trench and Stuff Redoubt. On this occasion the casualties were so high (396) that a composite battalion was formed.

Above: Hessian Trench and Stuff redoubt,

It was during this action that Williams fellow Gallipoli companion Captain Archie White was awarded the Victoria Cross. For his own part in the Somme fighting, William Peel was Mentioned in Despatches and soon promoted to Major, on 12 October he proceeded home on ten days leave.

In early 1917 Major William Peel completed a course at the XI Division Battle School before returning as second in command in the Battalion to the newly promoted Lt Colonel White VC. He occasionally took command of the battalion over the next few months as they moved around the ‘old’ Somme front on salvage and working parties. In June 1917 he again takes command of the battalion when Colonel White is granted leave. The war diary on the 2 June records him as Major Peel DSO, the gallantry award being announced in the London Gazette on 4 June but with no citation. The battalion soon moved up to the Messines Front taking over newly won ground on the Black Line from the 13/Royal Irish Rifles. On the 16 June whilst manning Odious Trench, the war diary states:

Shelling below normal during the day but enemy barrage started on our front system and approaches around 10 and lasted until 10.45am. Major Peel and 2/Lt Bath wounded at ‘A’ Coy HQ [11]

The nature of the wound remains a mystery, however it was slight enough for him to resume his battalion duties and sign off the war diary by August.

On the 14 August, the battalion attacked in the Ypres Salient towards Langemark along the Steenbeek River. They captured their objectives and held off frequent small counter attacks before being relieved by the 5/Dorset’s having suffered around 80 casualties. This would prove the last action for William Peel with the Yorkshire Regiment, for the first two weeks of September he commanded the battalion while resting near Poperinge, during this time he oversaw the introduction of new drafts, medal parades for the actions of the previous month and training in bayonet fighting, musketry and the use of new signal rockets.

On the 14 September, the war diary records ‘Major WR Peel DSO left the battalion to assume command of the 10 Manchester Regiment’[12]. His promotion to Temporary Lieutenant Colonel being announced in the army list a week later[13].

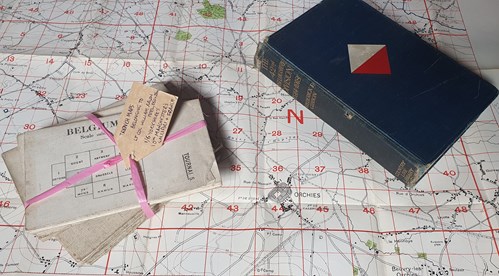

Above: The collection of maps William Peel was issued and used after taking command of the 10/Manchester Regiment, 14 September 1917

The 10/Manchester were a territorial battalion raised primarily from Oldham. As part of the 42nd (East Lancashire) Division they had also seen their first action in the Dardanelles, serving in the Helles Sector between May and December 1915. The battalion had arrived on the Western Front in March 1917 from Egypt, after a spell opposing the Hindenburg Line they had been transferred to Ypres in late August.

Whilst serving in the Menin Road Sector they were subjected to regular bombardment and ‘among the casualties of these ten days were Lieut-Colonel R.P. Lewis, 10 Manchester’s, killed by shellfire’.[14] He today lies in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery. William Ralph Peel was to be his replacement.

Above: Ypres Reservoir Cemetery (c) CWGC 2021

William's first real command of the battalion would take place in the unfamiliar coastal surroundings of Nieuwpoort, here they relieved their sister Division the 66th. Though away from the quagmire of the Ypres Salient, the Nieuwpoort sector was a curious one, and those who had expected a comparatively “cushy” time were disappointed. The town itself had ceased to exist, for it had never a day’s immunity from the enemy artillery and the bombing was hardly less continuous. It was also heavily gassed; the place being filled with gas on most nights.’[15]

As the war entered its final year January 1918 found William Peel and his battalion back in France in and around Givenchy, this was at this time a relatively quiet sector and aside from the occasional raid and regular gas bombardments (11 December saw an action that would lead to a posthumous VC for Walter Mills of the battalion is one such incident), the rotation between frontline stints and training in reserve became the normal way of life for the men of the 10/Manchester’s.

This routine was abruptly ended in late March 1918 when the German’s launched their ‘Kaiserslacht’, by the 25 March they were digging in west of ERVILLERS in direct support of the 40th and 59th Divisions who were falling back towards them. At 3.20pm they were attacked across their whole front and shortly afterwards:

'...troops immediately south withdrew, leaving our left flank exposed. The enemy gained possession of BEHAGNIES, a local counter-attack prevented the enemy from enveloping the right flank, the defence of ERVILLERS was held, the enemy never approaching nearer than 200 yards, being prevented from doing so by rifle and Lewis gun fire, no artillery support being forthcoming’[16].

Above: German troops advancing during the Spring Offensive of 1918

That evening the order to retire did arrive and the remainder of the month was spent in a fighting withdrawal, always in contact with the enemy as far as ESARTS De BUCQUOY, by this time they had received 85 casualties.

The retreat would continue across the ‘old Somme front’ throughout April and for his part in commanding the battalion the London Gazette announced a Bar to his DSO:

T./Maj. (A./Lt-Col.) William Ralph Peel, D.S.O., Yorks. R, attd. Manch. R.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Throughout two days very hard fighting he displayed great courage and marked ability in dealing with situations if considerable difficulty, going out under extremely heavy fire of all descriptions to select sites for machine guns and to resist advance posts of the companies of his battalion. On receiving orders to withdraw he directed the operation with great ability, remaining himself in the front line until the last of the troops had retired and all the wounded were evacuated. Throughout the operations his cheerful disregard of all considerations of personal safety was an example to his men, which inspired them with confidence and resolution.[17]

Above: A group of WW1 medals including a DSO and bar

Relationships between officers and men are often forged in fire, the Spring Offensive proved such a case for William who now firmly held the respect of his fellow officers and men.

After a relatively quiet May and June for the battalion, July afforded some home leave for William Peel before an offensive was launched on the 42nd Division front later in the summer. On 22 August, the 10/Manchester’s were involved in the successful assault on MIRAUMONT that led to capture of 40 prisoners, 18 Machine Guns, a Wireless set and an entire field dressing station. This reversal of hunter and hunted was wonderfully summed up in the Divisional history:

Now all was changed: the war had taken on an entirely new complexion, and “next spring” or even an earlier date, was spoken of with confidence, for at last, and for the first time, the Boche was on the run. His day was over and ours had dawned, though his numbers were still equal superior to ours, though his lines of defence were as formidable as the skill and ingenuity of the greatest masters of defensive warfare could make them, and though he would turn, snarling, and fight like a wolf at bay, our men had complete confidence in their skill with rifle and bayonet, their grit, and their will to conquer. They knew now that they were Jerry’s master. There was an accumulation of old scores to wipe off, and though the beaten individual Boche would generally be treated with contemptuous good-humour, there remained the deep loathing of all vile deeds by which the title of “Hun” had been earned.’[18]

On 22 September 1918 when the battalion had moved into positions NW of HAVRINCOURT WOOD, William Peel along with Captain Hardman and three other ranks were victims of a Mustard Gas shell landing in a forward trench, William was evacuated the following day, his third wounding in action of the war. His exact date of return is not recorded but by the 18 October 1918 the was diary states the battalion was once again preparing to go on the offensive:

East of Briastre – Lt Col WR Peel DSO addressed the battalion prior to going ‘over the top’, the battalion marched out of HERPIGNY FARM and relieved 1/7th Lancashire Fusiliers in the line in front of BRIASTRE, relief complete at 7.45pm [19]

The attack at 2am on the 20 October was part of the wider Selle River Crossing and the 10/Manchester’s were tasked with passing through the sizable town of Solesmes and clearing the railway embankment that passed directly across the divisional front behind it, two defensive positions dug in on contour lines were fiercely defended by the German 25th Division. An hour before the whistles blew a barrage fell on the battalion assembly positions causing numerous casualties, despite this, they were able to reorganise, push on, capture and consolidate their objectives. The acts of gallantry were numerous, the war diary in records the particular good work of Captain Taylor, Lt Jupp, 2/Lt Gregory, 2/Lt Morris, CSM Toogood, Sergeant Lees, Sergeant Newton, Corporal Fisher and Corporal Revell during the action, all plus a number more were awarded medal ribbons by the Divisional Commander Major General Solly-Flood a week later for the action, it had not been one without cost however, with 6 officers and 20 other ranks becoming casualties.

The 10/Manchester’s were not directly involved in the crossing of the Sambre Canal on 4 November 1918, they did however occupy the Foresters House on the edge of the Forest of Mormal, taking it over from the 2/Manchester Regiment and Wilfred Owen who would be killed that same day, the building, still standing today houses a museum to Owen’s work.

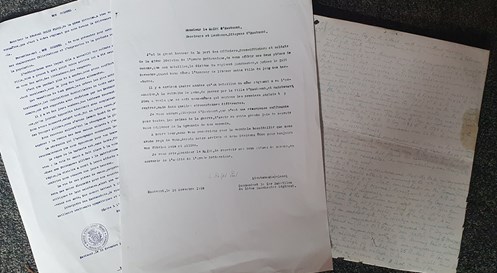

Above: Personal papers relating to William Ralph Peel, including his diary referencing the Foresters House 4 November 1918

The final action for the 10/Manchester’s in the war takes us back to the start of this article, on 8 November the battalion pushed out fighting patrols from the BOIS du HAUTMONT towards the village in an advance to contact operation. The leading elements entered the outskirts of the village at 11am and Captain Taylor set about immediately constructing a footbridge across the Sambre. This brought the battalion to within 200 yards of the enemy defensive positions. Throughout the day a firefight ensued from the loopholes in buildings occupied by the Oldham men, British Artillery joined the fray and this eventually forcing the Germans back and out of the town. This however brought about an intense barrage on the recently evacuated positions, this lasted for several hours and seemed aimed on the main square and ‘Taylors Bridge’ in particular. The German Battery was located and subjected to heavy artillery itself, eventually silencing it. What made the day quite remarkable was not only the speed of the Manchester’s advance, but the assistance given to them by the civilian population, as the war diary records:

On the battalion relieving the town, great enthusiasm was displayed by its inhabitants. They greatly assisted in building the bridge, the leading patrols were received by the Maire and English prisoners that had been in German hands. Very great assistance was rendered by the inhabitants in giving positions of enemy machine guns, in this they displayed great bravery. Later in the day unfortunately, many became casualties during hostile shelling. A 4.5 Howitzer a 77mm gun and limber, a motor lorry and 1 tractor were captured by the battalion.’ [20]

The words were taken directly from William Peels handwritten notes of the day, his own role was not unrecorded either for the following year the London Gazette would publish the citation for a second Bar to his DSO:

T./Maj. (A./Lt-Col) William Ralph Peel DSO, 6th York Regt, attd 10th Manchester Regiment. For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the operations east of the Forest de Mormal from 6th to 8th November 1918, He led his battalion for four days in continuous rain, without shelter, and captured the town of Hautmont. To accomplish this, he had to supervise the construction of a hasty bridge over the Sambre river and cross it whilst enemy troops were still in the town.[21]

His personal diary goes onto record on 16 November 1918:

Whole battalion and representatives of all units of the Division formed up in the square. Lt Col WR Peel DSO presented the 4.5 Howitzer and 77mm guns, captured by the battalion on the 8th, to the Maire and citizens of Hautmont. The Maire responded with an address, the battalion then marching past the Divisional Commander and the Maire.

Above: The award of a howitzer and field gun to the people of Hautmont 16 November 1918

Hautmont today no longer has the guns on display, the square is very recognisable though the bandstand has been replaced by a water feature. A short stroll away the site of ‘Taylors Bridge’ has a more modern crossing in place yet, in its shadow, stand the local war memorial and scars on the surrounding walls.

It attracts few British visitors these days, but I try to visit when I can, why my interest? Well not only was William Peel an inspirational soldier who would take part in the Gallipoli Landings, Somme, Ypres, the March Retreat and the Advance to Victory, not only was he wounded three times, awarded three DSO’s and twice mentioned in despatches, not only because he joined as a subaltern and leave as a battalion commander, it’s really because I my good friend and fellow WFA Member Alan Barker gave me the set of 1/20,000 maps of Northern France he was issued when he took command of the 10/Manchester Regiment, the actual maps he used throughout that last year of the war and maps I treasure over a century after the event.

I will never forget the efforts of William Ralph Peel, the Friend, Liberator and Avenger of Hautmont.

Above: Hautmont Square today, the guns and bandstand long gone, the square outside the church is easy recognisable

Article by Clive Harris

[1] Extract of the speech given by the Mayor of Hautmont, 16 November 1918, Author’s collection

[2] Extract of the speech given by Lt Col W.R. Peel, 10/Manchester’s, 16 November 1918, Author’s collection

[3] Mayor of Hautmont Speech, Ibid

[4] McCrery N. The Vanishing Battalion, London: Simon & Schuster Ltd, (1992), p63

[5] Wylly, H.C. The Green Howards in the Great War, Yorkshire: Richmond, (1926), p226

[6] Aspinall-Oglander, C.F. Official History of the Great War – Military Operations – Gallipoli Vol 2, London: William Heinemann Ltd, (1932), p381

[7] Ibid

[8] Westlake, R. British Regiments at Gallipoli, London: Leo Cooper, (1996), p50

[9] WO96/4299 The National Archives

[10] Malvernian Magazine, November 1916.

[11] WO/95/1809(page40), 2/Yorkshire War Diary, National Archives

[12]Ibid page 49

[13] WO/339/20289, Service Record William Ralph Peel, National Archives

[14] Gibbon F, The 42nd (East Lancashire) Division 1914-1918, London: Country Life, (1920), p102

[15] Ibid, p106

[16] WO/95/2658 (page 169) The 10/Manchester’s War Diary, National Archives

[17] Supplement to the London Gazette, 16 September 1918, p 10859

[18] Gibbon, The 42nd (East Lancashire), p159

[19] WO/95/2658-2 (page 147), 10/Manchester’s War Diary, National Archives

[20] WO/95/2658-2 (page 156), 10/Manchester’s War Diary, National Archives

[21] Supplement to the London Gazette, 10 December 1919, p 15280