General Maude and the Recapture of Kut

- Home

- World War I Articles

- General Maude and the Recapture of Kut

With temperatures ranging from freezing to 130ºF (50ºC) the campaign in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) was undertaken in one of the most inhospitable climates imaginable. Despite being a side-show to the main battles of the First World War in France and Belgium, the Mesopotamian campaign lasted virtually the entire period of the war.

A mission had taken place in 1914 to take the strategically important oil facilities at Basra and Qurna. This was successfully completed by troops of the ‘Indian Expeditionary Force D’. Although the region was part of the Ottoman Empire, there was little strategic reason to attempt to defeat the Turks in this hot and diseased area once the oil installations had been secured, however, the ease with which Basra had been taken, led to a disastrous ‘mission creep’.

Despite the lack of logistical infrastructure, suitable boats, maps, medical supplies, equipment and reinforcements, and in the face of the usual spring floods, mud, heat and flies, the commander of the expedition, Major-General Sir Charles Townshend, ordered Force D to proceed up the Tigris river.

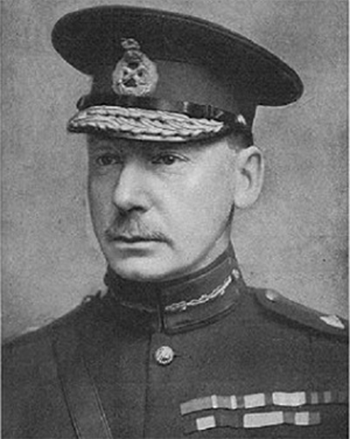

Above: Major-General Sir Charles Townshend

This advance took them to within 25 miles of Baghdad. However, the Battle of Ctesiphon in November 1915 resulted in a stalemate and heavy casualties to both sides. Over 960 fatalities of this battle are commemorated by the CWGC on the Basra Memorial.

With their lines of supply overextended, and medical services overwhelmed, Townshend ordered the troops to retreat to the town of Kut-al-Amara.

Above: Turkish troops proceeding down the River Tigris on rafts from Diabekir to join the besieging army at Kut-el-Amara. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum HU 52443.

At Kut, Townshend formed a defensive position which he correctly perceived would be strong enough to repulse Turkish attack.

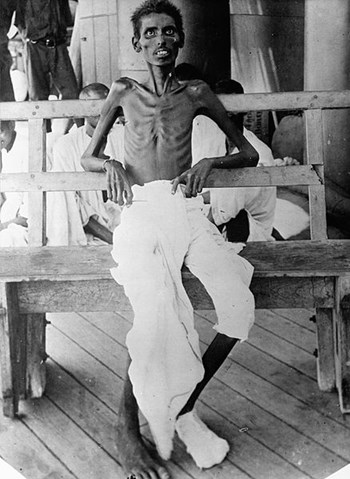

Above: An emaciated Indian army soldier who survived the Siege of Kut

Despite a number of attempts in early 1916, the siege which ensued could not be relieved by Allied troops and after five months, Townshend surrendered his forces to the Turks on 29 April 1916. About 13,000 men (including over 3,000 non-combatants) went into captivity.

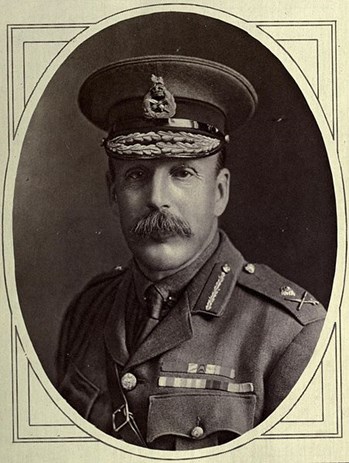

The humiliating defeat, coming so soon after the withdrawal of troops from Gallipoli, was, in the view of the Government, likely to result in the loss of prestige in the east, and rather than withdraw forces, it was decided to send reinforcements to the newly appointed commander, General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude (image below).

After the evacuation of Gallipoli in January 1916, a parody of the Victorian parlour song, Come Into The Garden, Maud became popular with the troops. It was inspired by the actions of General Maude, who refused to leave the beach until he had been reunited with his servant and baggage:

Come into the lighter, Maude,

For the fuse has long been lit,

Come into the lighter, Maude,

And never mind your kit,

I’ve waited here an hour or more,

The news that your march is o’er.

The sea runs high, but what care I,

It’s better to be sick than blown sky high,

So jump into the lighter, Maude,

The allotted time is flown,

Come into the lighter, Maude,

Or I’m off in the launch alone.

Maude builds up his forces

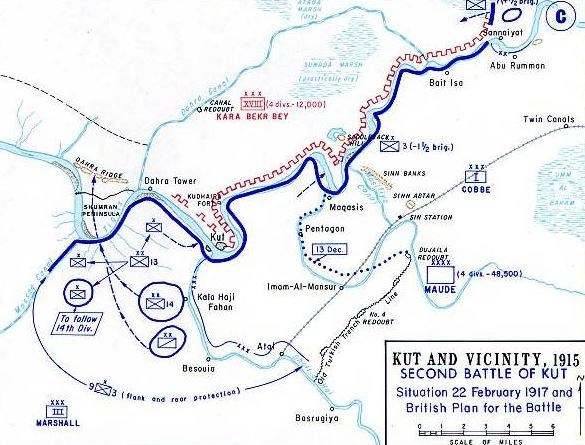

For six months Maude built up his troops, and eventually commenced his campaign on 13 December 1916. Rather than the rapid exploitation that had taken place under Townshend, this time the advance was slow and deliberate. A total of 50,000 men advanced on both sides of the River Tigris. Heavy rain slowed the advance but on 29 January, the fortified Khadairi Bend was taken.

The advance continued with Kut being Maude’s immediate objective. Faced with a quagmire of mud, there was little opportunity for movement except by river transport. However, by attacking at the Shurman Bend (6 miles west of Kut) on 17 February, Maude forced the Turkish commander to withdraw from the town a few days later.

Above: map of the general situation at Kut on 22 February 1917

During this period, an act of gallantry resulted in a Victoria Cross being awarded to Serjeant Thomas Steele (image below).

Thomas Steele's VC citation reads:

On 22 February 1917 near Sanna-y-Yat, Mesopotamia, at a critical moment when a strong enemy counter-attack had temporarily regained some of the captured trenches, Sergeant Steele helped a comrade to carry a machine-gun into position. He kept this gun in action until relieved and was mainly instrumental in keeping the rest of the line intact. Some hours later another counter-attack enabled the enemy to reoccupy a portion of the captured trenches and Sergeant Steele rallied the troops, encouraging them to remain in their trenches and leading a number of them forward, helped to re-establish our line. On this occasion he was severely wounded.

Above: Recapture of Kut-al-Amarah, 24 February 1917. British Infantry marching through. Image IWM Q 25224

Kut was evacuated by the Turks on 24 February, but it was not the end of the fighting in the area.

Besides occupying Kut, the British took the enemy positions from Kut to Sanna-i-Yat, together with over 1,700 prisoners.

Above: The original caption reads 'An officer of the Graves’ Registration Commission locating the resting place of an officer buried in the parapet of the Sanna-i-Yat trenches.' From The War Illustrated

Operations continued on 25 February. These started with forward elements of the British and Indian force advancing up the left bank of the Tigris, while the Cavalry Division moved to the north. By mid-morning, the Hertfordshire Yeomanry established contact with the Turkish rearguard which was positioned on a canal. The yeomanry regiment was ordered to contain the Turks until the arrival of the British infantry. After half an hour various infantry battalions reached the canal position, where they came under Turkish shell fire.

The British Artillery pushed forward into action against the Turkish guns. This enabled the leading battalions to make progress, rapidly driving into the Turkish posts.

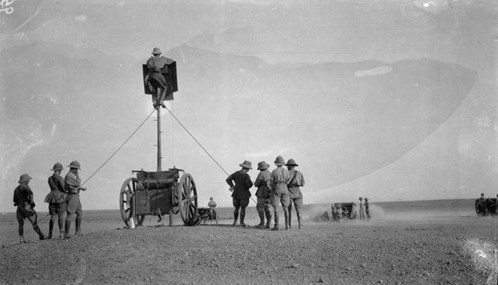

Above: The commander of a Royal Artillery battery spots for his guns from the top of a limber pole ladder. The use of such ladders was often the only way to get a useful view of the battlefields on the flat plain along the River Tigris. Image IWM Q24261

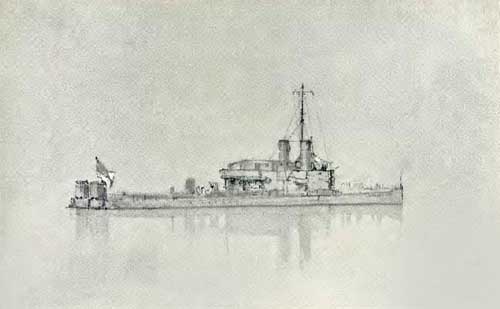

The advance now received support from the Naval Flotilla - Tarantula, Mantis, Moth, Gadfly and Butterfly - which had arrived and was co-operating with the Brigade guns.

Above: HMS Mantis. These vessels were designed to operate in shallow fast-flowing rivers

The Official History described the scene:

By 12.30 p.m [...] it was clear that the 38th Brigade's advanced line - 6th King's Own, 6th East Lancashire and 6th Loyal North Lancashire, in this order from the right - had been definitely checked by heavy rifle and machine-gun fire from some seven hundred yards from the enemy's trenches and was beginning to dig itself in. At this hour the fourth Battalion of the Brigade, the 6th South Lancashire, was sent to the right to try and turn the enemy's flank. Passing through the line of the Hertfordshire Yeomanry, this Battalion effected a lodgement in a section of the enemy's line about a mile and half north of the Tigris bank, but found itself still south of the enemy's left flank.

At this point in the 6th Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment became involved. The Battalion's War Diary states:

…Enemy encountered about noon, flank guard became merged with advance guns and captured watercourse from enemy. Enemy still held left of watercourse. Party led by 2nd Lt. Jackson cleared watercourse on left with bayonet in face of terrific machine-gun fire, rifle grenades and bombs. 2nd Lts Jackson and Jefferson killed, 2nd Lts. Fletcher and Sharpley wounded, 21 men killed and 58 wounded.

The CWGC Debt of Honour database records 24 men of the battalion were killed in this action. All are commemorated on the Basra Memorial.

Above: The Basra Memorial in its original location (circa 1930) and (below) its present location which is some distance west of the city, in the desert.

The above bald statement in the Battalion War Diary, not untypically, hides the drama of the situation and the courage of individuals. One of the men who showed outstanding bravery in this action was Private John Readitt (photo below).

An account in Empire News dated 8 July 1917 states that he was ‘the only survivor’ of the first four bombing raids along the watercourse. It goes on to describe that during the fifth raid, Readitt had to rally the bombers who had scattered in the face of heavy enemy fire, and eventually he moved them up to the Turkish barricade, 'which formed the main enemy position and was the chief obstacle to the advance'.

Here the enemy counter-attacked, but in spite of the fact that the enemy concentrated on him a deadly fire and every sniper in the Turkish ranks seemed to be shooting at him, Readitt never abandoned his so-as-you-please style of retirement. Whenever the enemy pressed him too closely he would just turn and let them have a bomb, which scattered them in all directions.

Finally he was joined by another bombing party and then he made his most determined stand. Under his leadership, the bombers drove the enemy back once more, and after a fierce fight the whole position was captured and consolidated.

The Turkish commander whom we captured later in the day, said he had never seen anything finer than the way that stripling (Readitt is only 20 years of age) had stood up to a whole army.

John Readitt was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions. The citation for this award reads as follows:

On 25 February 1917 at Alqayat-al-Gaharbigah Bend, Mesopotamia, Private Readitt advanced five times along a water-course in the face of heavy machine-gun fire at very close range, being the sole survivor on each occasion. These advances drove the enemy back and about 300 yards of the water-course was made good in an hour. After his officer had been killed, Private Readitt, on his own initiative, made several more advances. On reaching the enemy barricade he was forced to retire, but gave ground slowly continuing to throw bombs. When support reached him he held a forward bend by bombing until the position was consolidated

Promoted to Sergeant, Readitt was decorated for gallantry by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 26 November 1919. After the Great War, he returned to work with his father and took over the family business as a clogger and shoe repairer. John Readitt died on 9 June 1964, aged 67 years, at his home in Bury Brow, Clayton and was buried in Gorton Cemetery.

The recapture of Kut led to the eventual defeat of the Turks in Mesopotamia. It is doubtful, however, that this campaign shortened the war in Europe by a single day.

Above: River steamers approaching the lending stage at Kut el Amarah. Image IWM Q20599

Above: Indian Porter Corps open air theatre at Kut. Image IWM Q 24576

On to Baghdad

After the recapture of Kut, Maude was able to continue his advance up the Tigris and took Baghdad the following month. He was not able to savour this victory for long as he died of Cholera on 18 November 1917, shortly after drinking some contaminated milk. General Maude is buried in Baghdad (North Gate) Cemetery. The cemetery is located in the Waziriah area of the Al-Russafa district of Baghdad.

Above: General Maude’s tomb in Baghdad (North Gate) Cemetery. Image courtesy of the BBC.

Aftermath

It is believed that over half of the surviving Kut garrison of 13,000 died of ill treatment and neglect during forced marches of hundreds of miles and in subsequent captivity. Having been held in luxurious accommodation, General Townshend survived the war. When the news of his special treatment was made public, and compared to the ill-treatment meted out to his men, his reputation was irreversibly ruined.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association.

Further reading (Online Book):

On the Road to Kut: A Soldier’s Story of the Mesopotamian Campaign

The anonymous author was part of the 6th (Poona) Division, Indian Army. The high temperatures forced much inactivity on the commonwealth troops through the campaign. The author wrote “From 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. it was hot. From 9 a.m. to 12 damned hot. From 12 to 5.30 much too damned hot.”