Holzminden ‘Colditz’ of the First World War?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Holzminden ‘Colditz’ of the First World War?

The Second World War is probably more associated with escape exploits of prisoners of war, but there were a number of daring escapes (some more successful than others) during the Great War. The escape of 29 officers from Holzminden PoW Camp is probably the first ‘great escape’.

Holzminden was a prison camp situated sixty miles south west of Hanover. Opened in September 1917, it housed around 500 officers and around 100 ‘other ranks’ who acted as orderlies for the officers, in two large four storeyed buildings (Kasernes). Many of the officers were deemed to be ‘troublesome’ having attempted escapes from other camps.

Above:Kazerne B in Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp, with British prisoners and German guards. Late 1918 (public domain)

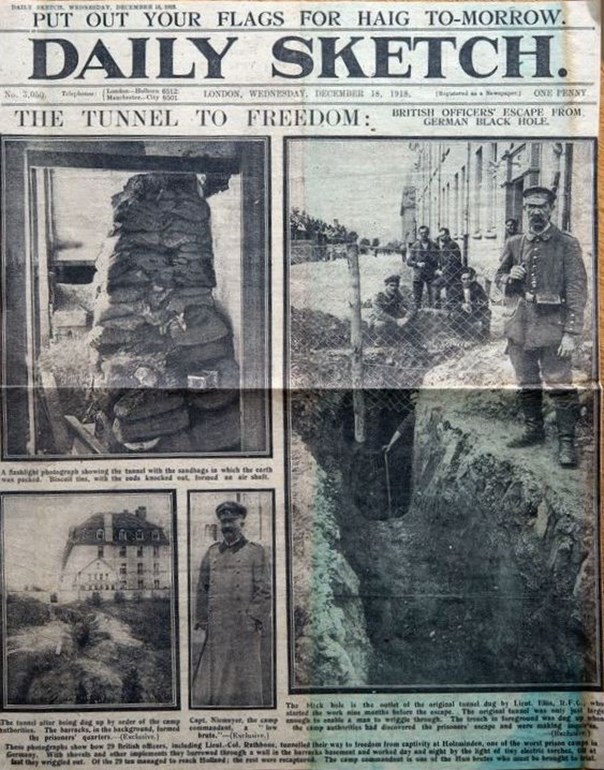

The Commandant of the camp was Hauptmann Karl Niemeyer, who spoke broken English. He had lived in the USA before the war, prompting the nickname of ‘Milwaukee Bill’. He boasted that he knew English ‘from A to Z’. When he heard of the escape, he is reported to have said ‘Vell, Gentlemen. You think I know nodding at all, But I tell you I know damn all’ (reported in the Oxfordshire Weekly News).

Caption - Karl Niemeyer, Commandant of Holzminden

Above: A caricature of Hauptmann Niemeyer - Wikipedia

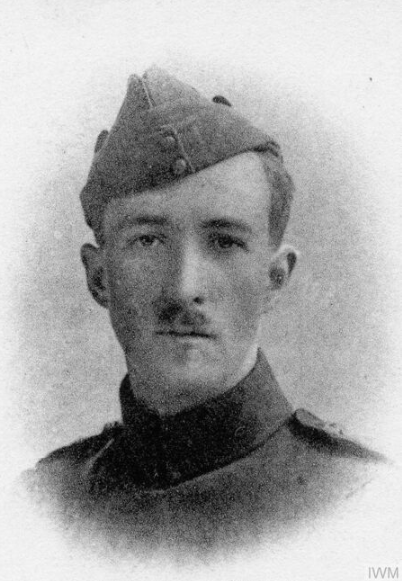

Niemeyer ran a harsh regime in the camp, frequently punishing prisoners with solitary confinement, and leading to the nickname for the camp of ‘Hellzminden’. His regime was also arbitrary and vindictive. One prisoner who reportedly particularly suffered at his hands was William Leefe Robinson VC.

Above: William Leefe Robinson VC - Wikipedia

Leefe Robinson had been awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in September 1916 when he downed a German airship over England. He was posted to France in April 1917 but was captured on his first patrol after being shot down. He was moved around a number of camps having made several unsuccessful escape attempts, ending up in Holzminden. He would later die of influenza on 31 December 1918 but newspaper reports carried stories that his relatives contended that his death was a result of ‘the refinement of torture’ practised on him by Niemeyer.

After the war, accounts from repatriated prisoners of war were published in various newspapers citing examples of the regime at Holzminden. As an example, Captain Enos, who spent several months in Holzminden was later reported in the Leeds Mercury as saying

‘The Commandant was a beast….Here I had Lieut. Robinson for my neighbour and the Commandant did everything possible to annoy Robinson. One day, the Commandant objected to British Officers wearing shorts and put three of them in the cells for protesting that it was a regulation dress of the British Army’.

In similar vein, Lieutenant Hay’s account of Holzminden in the Bexhill on Sea Observer was succinct

‘Holzminden – worst of all [camps]. Also 10th or Hanoverian Army Corps. Ten stoves, out of doors in barrack square, to cook on. If lucky, one meal a day after standing hours in cooking queue. Knocked out of bed with butts of rifles at dawn most mornings. Commandant frequently drunk and when drunk used to make guard and sentries fire volleys through windows’.

Lieutenant Cyril Ball, the younger brother of Captain Ball VC, was also at Holzminden and remarked that

‘the fact that I was the brother of Captain Ball seemed to make my treatment worse. I was put in prison for three days for smiling at the Commandant’. (reported in the Aberdeen Evening Express).

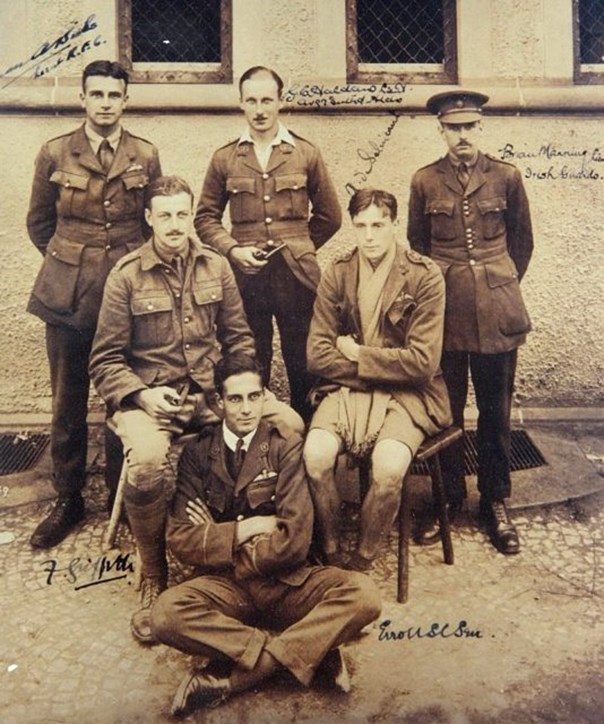

Caption – Prisoners at Holzminden – WarHistory online

Although Niemeyer would tell new prisoners that there was no point in trying to escape, in the first month after the camp opened, 17 prisoners escaped, although all were recaptured soon after. It was in October 1917 that the plan for ‘the great escape’ was hatched – involving the construction of a tunnel from the section of Kaserne B which housed the orderlies to beyond the wire. The tunnellers used cutlery and any other implements that they could get their hands on…but it was slow, hard work which could only be carried out for a few hours each day and complicated by the fact that officers were forbidden to enter the part of the Kaserne which housed the orderlies.

Alongside the actual digging of the tunnel, work was carried out to create clothing, uniforms and papers for the aspiring escapees, alongside lessons in German. By the end of June 1918, it was estimated that the tunnel had reached the rye field on the perimeter of the camp – but it was discovered that the tunnel was still a few metres short but a row of beans just before the rye field would provide some degree of cover, so only a further few yards of tunnelling was necessary. Finally, on 23 July 2018, the tunnel was judged to be completed.

Above: The Daily Sketch – December 1918

The plan was that those directly involved in the tunnelling work would go through first, about 20 in all, and then be followed by what was called ‘the ruck’ – enabling around 90 or so prisoners to escape. On the night of 23 and 24 July 1918, all went well for the first 29 escapees, but when the 30th went through the tunnel with hiking gear, he got stuck and it partially collapsed. Although the trapped man was rescued, the tunnel was blocked. On the morning of 24 July 1918, the farmer who owned the rye field reported to Niemeyer that his field had been trampled – further inspection revealed the mouth of the tunnel. Niemeyer was reportedly ashen faced when he discovered the extent of the escape. The German authorities offered a reward of £250 for each escapee returned to the camp.

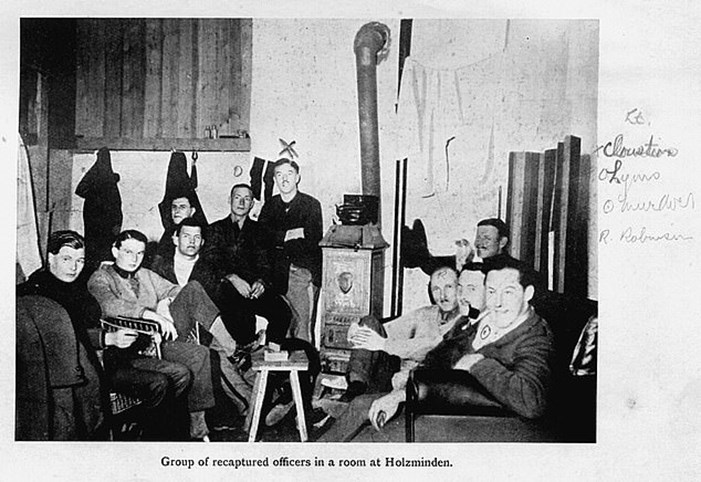

After the escape, the camp regime grew ever harsher, as later recounted by a former prisoner

‘For a time after this episode, life at Holzminden was irksome and unbearable. Niemeyer ‘had the wind up properly’. He behaved like a spiteful schoolboy. The prisoners could do practically nothing without the guards interfering.’ (reported in the Oxfordshire Weekly News December 1918)

Of the 29 who managed to escape, only 10 reached neutral Holland. But the report of the escape filled the newspapers in the final stages of the war.

Above: A group of recaptured officers in a room at Holzminden

The first of those to reach safety was Lieutenant Colonel Rathbone, a German speaker, who crossed the border to Holland after just five days on the run, travelling by train to Aachen on the Dutch border. On his arrival in Holland, he immediately sent a telegram to Niemeyer

‘HAVING A LOVELY TIME STOP IF I EVER FIND YOU IN LONDON WILL BREAK YOUR NECK STOP’

The story of the escape and accounts from those who managed to reach Holland featured in many newspapers over the following weeks and months. A number of those who successfully escaped were awarded the Military Cross, with Rathbone receiving a Bar to his Military Cross.

Lieutenant John Keith Bousfield, Royal Engineers and Royal Flying Corps, had been shot down in April 1917 and had spent time in two different camps before going to Holzminden, making two unsuccessful escape attempts. In August 1918, the ‘Hendon and Finchley Times’ carried a report of his invitation to Windsor to tell the King of his escape and also to receive the Military Cross, awarded for his actions during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Above: Lieutenant John Keith Bousfield

Captain David Gray of the Royal Flying Corps had been shot down in September 1916. He had a good command of a number of languages and was another of the successful escapees.

Above Left: The tunnel. Above right: Captain David Gray

Second Lieutenant Jock Tullis, Royal Flying Corps had been captured in September 1916.

Above: Jock Tullis – RAF Benevolent Fund

Edward Wilmer Leggatt MC was shot down in August 1916. After capture, he was in various prisoner of war camps before arriving at Holzminden in May 1918.

Above: Edward Wilmer Leggatt, Royal Flying Corps– IWM

After the war, those who had organised and taken part in the ‘great escape’ – whether successfully or otherwise - would meet for a reunion dinner. In July 1938,on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the escape, many newspapers featured accounts of the escape to coincide with the reunion dinner on 23 July 1938, including somefrom the unsuccessful escapees. Second Lieutenant Arthur Morris MC had served in 4 Tyneside Scottish and was one of the organisers of the escape. By 1938, he was living in Dundee and recounted that

‘…at the other side of the rye field [we] wished each other goodbye and good luck before splitting up and going in different directions in pairs. Paddison and I were together. My partner injured his foot and this hampered us considerably. We were 23 days ‘out’ in Germany before being recaptured. I was caught while swimming the River Ems, only about seven kilometres from the Dutch Border’. (Dundee Evening Telegraph May 1938)

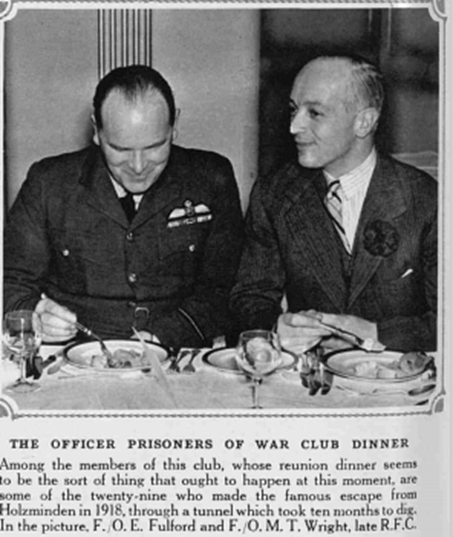

Above: The reunion dinner – The Tatler 1939

Article by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary – The Western Front Association

With thanks to Derek Bird, Chairman, North Scotland branch of The Western Front Association who drew my attention to this story and also gave me access to a talk he gave on this subject.