I escape from Groningen!

- Home

- World War I Articles

- I escape from Groningen!

After the fall of Antwerp in 1914, an R.N.D. Able Seaman is interned in Holland but escapes to England.

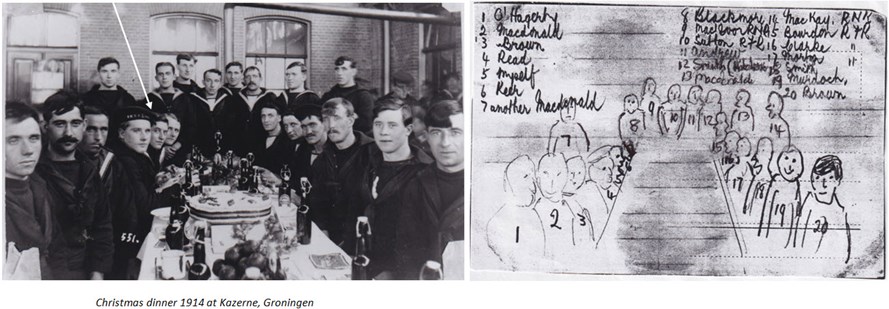

The following is an extract from the account of Able Seaman John Henry Bentham, Benbow Battalion, Royal Naval Division which, for reasons of brevity, omits many photographs and details of camp life, incidents during the escape, and his eventual return to his family and his commission. The complete account can be found in the issue 13 of Len Sellers' R.N.D Journals on the WFA members only webpage.

------------------------------------------

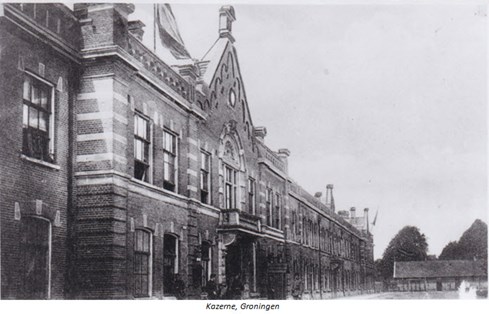

At length, at about midday on Sunday 11th October just a week after leaving Walmer, we arrived at Groningen. What a week of crowded adventure! Vast crowds witnessed our arrival and it seemed a mixed reception as being only a few miles from the German border, their sympathies lay with Germany. We were marched direct to the Kazerne which was the military barracks. They were not inviting having been occupied by the Landsturm. The sleeping accommodation was comprised of large rooms with iron bedsteads and to economise in space were placed one on top of the other. These beds were all jammed together and the rooms were terribly overcrowded and the atmosphere at night was dreadful. We were all mixed up and those of us who had come from decent homes were rather appalled by the conditions that we were to live under and for how long! We were then allowed to write one postcard each. A dirty unshaven crowd we were and everyone had a week's growth on his face, Very few had any money and theirs was quickly expended on sardines etc, which we could purchase from a little Jewish man who came into the barracks with a barrow, and built up a good business with gingerbread.

We were paraded next morning and learnt that our officers had been placed on parole and were living in hotels in the town and we were directly under the control of the Dutch Commandant and our own Chief Petty Officers. The latter had never had so much authority before and were all ex regular naval ratings, and had little or no time for the R.N.V.R. This was very noticeable. We were detailed for odd jobs in cleaning up the place etc in the morning and the rest of the day we had nothing to do except talk and discuss our adventurous week over and over again.

Some of the sentries were open to bribes and at night they would let a lady of easy virtue in the gate and into the sentry box with a sailor for a few guilders, or would smuggle schnapps (a raw spirit) in. The older hands soon found out that if they had toothache, they had to go to the town dentist and many were the men who invented toothache, were taken to the dentist by a soldier where they had a perfectly good tooth extracted and then accompanied by the guard visited cafe after cafe and ended up by coming back to the camp arm in arm, both guard and sailor drunk as fiddlers. Schnapps was used to incite the Stornoway fishermen to fighting, and many a head was split open, whilst I crawled well out of the way until all was quiet again

Months slipped by and just before Christmas our officers who had been having a good time and made much fuss of by the girls, received an order from the Admiralty to give up their parole and attempt to escape. Fifteen tried to escape in one day and the confusion that prevailed among the Dutchmen was too funny for words. Germany was kept well informed of this and immediately accused Holland of aiding and abetting as she was anxious to drag Holland into the war just then. However, nearly all of the officers were caught and brought back to our barracks an locked in a large room on the first floor. The poor old Commandant was worried out of his life and could visualise being called upon to resign. Sentries were posted all round the building. During the evening the officers stuffed a uniform with pillows etc. and lowered the dummy to the ground, giving a low whistle at the time. Immediately sentries rushed from all sides and grabbed the dummy, whist all the officers leaned out of the windows, roaring with laughter. Shortly after this, the officers were taken away and sent to the Island of Urk and once again we were at the tender mercies of the Chief Petty Officers who revelled in lording it over us.

About this time I had failed to salute a Dutch officer and stated that he seemed the same as a postman or tram driver and I could not tell the difference. This was regarded as a direct insult and I was punished by having to clean lavatories for a fortnight for the Dutch guards as well as for the men. It was freezing cold and I could hardly hold the scrubbing brush. Never have I had such a detestable job for the Dutch soldiers had no idea of hygiene. I discussed with my particular friend our chances of getting away and many different ways and means were gone into. One thing stood out clearly and that was one of us must learn the language thoroughly and as I had picked up quite a lot already, I agreed to go ahead and learn all I could and commenced by haunting the Guard Room and talking to the Dutchmen. About the middle of May, we thought that we were all prepared. We had got civilian suits sent over from England in very small parcels like one sleeve or half a jacket at a time as large parcels likely to contain civilian clothing were opened by the Dutch authorities and confiscated. Gradually all these pieces were received and sown together by the camp tailor who kept quiet about it all and the suits were stuffed in our straw palliasses.

Every Sunday afternoon, Timbertown [the camp] was like a Zoo and thrown open for the Dutch inhabitants to walk round and see how we lived. This was a very popular pastime fo the Dutchmen and their wives and families. The hours were from 2.00 - 4.00 p.m. and here we thought was an excellent way of getting out of camp. One day an organised search for civilian suits took place and of course many were found. I pleaded sickness and stayed all day in my bunk, but Alec my friend got nervy and dropped his in the piano in the Recreation Hut and I heard afterwards how scared he was when the Dutch guard stood by the piano talking about the search. Luckily, no-one looked inside it or attempted to play it just then. Money was the next problem - we were paid one guilder (1/8d) every ten days which was the Dutch army rate of pay, the balance was credited to our account at the Admiralty. I wrote to my bank who very kindly arranged with their agents at the Hague to visit me and pay me so much each month, which I carefully saved. There were many snap checks for civilian clothes but somehow we generally got wind of it and were prepared.

One fine sunny day, Alex and I decided to make our attempt. After dressing in difficulty in a lavatory we came out and mingled with the crowd just as the warning bell rang for visitors to depart. We joined in the tail of the queue and tried to get out in the crowd. We were just through the wicket gate when the Sergeant of the Guard asked me my name so I replied gruffly "Herr Stophasse", that being the name of my girl. The sergeant then said something that I did not understand so I replied with a non-committal "Ja!" and was almost through when I saw him beckon two of the guards. Realising the game was up, I whispered to Alex to get back and hide. Turn about, we fairly barged into the stream of people emerging through the gate, pushing and scrambling and hearing shouts in our rear. Back into the camp, we dashed through lavatories, bath huts, workshops, finally diving into our hut through the window and whipped off my clothes and had my uniform more or less on before the guard searched our hut. It was a narrow squeak and proved to me that my Dutch was certainly not good enough and that I must improve it before we had another go.

I then got my girl to visit me nearly every day and held conversation with her through the wire on the wood side. One day I was talking to her when a new Dutch Officer, a Lieutenant Von Horst, late of the Groenen Jagers (Green Hunters) who was I think a German and hated us like poison, came along and ordered me away. I disliked being treated like a dog especially in front of my girl, and so moved very slowly talking to her as I did so. Von Horst snatched a rifle from the sentry, rammed home a cartridge and pointing the weapon at me, stated that if l did not move before he counted three he would shoot. He was livid with temper and so was I because it was so unjust. However, I wasn't going to be yellow in front of my girl so I called out goodbye to her and stood there. Before anything else could happen Major Van Baerle came along and he was very popular. He dismissed me to my hut and went off with Von Horst. Naturally I was punished and my leave stopped. One dark night Von Horst was set on by a gang of our lads and given such a hiding that he never showed his face again and was transferred from the camp.

I got my leave privileges back again in due course. During the following week we planned all the details [of our escape]and on the following Sunday, 15th June, we were strung up to concert pitch. We carefully dressed, having civilian suits under our sailors uniform and I was glad of the full trousers etc. as our caps, collars and tie we were able to stuff into our socks. Then, as the Church party went down the drive out of camp, we ran up to the gate and asked if we could catch up with them. We were told to run, but once through the gate we stopped to do up our shoe laces and by the time this was finished the Church party were just going round the comer. Quick as lightning we slipped round out of sight and into the wood, having made certain there were no shouts or alarms. We plunged into the thickest part and were therefore clear.

Off came our uniforms which we pushed under a bush, put on collars and ties and caps well pulled down over our eyes, then we slouched into Groningen. We even picked some bluebells and stuck them into our buttonholes. We must have looked like a couple of hobos or unemployed as my suit came from a friend unbeknown to my people and just fitted where it touched. Naturally we both felt very self-conscious. We then started to walk to Assen, 25 miles away, and by midday we were well on our way. I walked well ahead of Alex and each policeman that we passed I imagined eyed us with suspicion. In fact one mounted policeman going in the direction of Groningen, kept turning round in his saddle and looking at us.

At length, very footsore, weary and hungry we arrived in a decent village where we entered a cafe and I ordered, in my best guttural Dutch, two glasses of beer. Everything seemed fine, no questions were asked but just as I was about to take a long drink, Alex in his excitement knocked his glass over. He tried to mop it up with his cap, but the waiter saw what had happened and came towards our table. Not knowing how to explain the mishap in Dutch, I hastily drank my beer and decided to leave quickly. I said "Good Day" and we walked out. Once clear of the village, I proceeded to tell Alec just what I thought of him. At about 5.30 p.m. we arrived in Assen and I had huge blisters on my heels and knew we must seek shelter for the night. Choosing a quiet hotel off the main road, we walked in and again I used my best Dutch and asked for rooms and something to eat. After looking at us for what seemed an age, the proprietor led the way upstairs muttering to himself. In the Billiard Room I noticed four policemen which did not help to put my anxious mind to rest. Our host showed us into a room asking us whether we liked beefsteak etc. and then he left us. Our nerves were at such a pitch that we thought we heard the proprietor talking about Groningen.

Anyway, we had a good wash and then sat on the bed waiting for him to return. After a long time he returned and took us downstairs to a small room and there on the table were delicious veal steaks and fried potatoes and mugs of beer. He then went out and we heard the key turn in the door. So the game was up ! All our worrying and trouble for nothing. Poor Alex had tears in his eyes. We were so hungry however, that we sat down and cleared the table of everything - come what may, we had lined our insides !

Waiting for the inevitable seemed an age, but at length the key turn and instead of the police we expected to see, the proprietor came in alone. Coming straight up to us, he said, "You are escaped sailors from Groningen", then elaborated on what his duty was etc. and that the police offered 18 guilders for our capture. I cared nothing for attempts to blackmail but stated that we hadn't much money and that we would give him 50 guilders if he would keep quiet. He greedily accepted and took 25 guilders on account, then he took us upstairs again bringing up a bottle of schnapps and told us that we were safe until morning when he would arouse us at 5.30 a.m. Out he went and locked the door to protect us, he said. Would he now double-cross us and go to the police to claim 36 guilders ? Apparently his word was his bond like so many Dutchmen. As nothing happened, we made plans for the following day an eventually dropped off to sleep. We were awakened early next morning, had a jolly good breakfast of ham and boiled eggs and the proprietor then gave us detailed instructions of the railway service and directions to the station. The main feature of his instructions was that we were not to change but to go straight through to Rotterdam.

Walking boldly into the Booking Hall at the station, I asked for "Twee kartjes naar Rotterdam (Two tickets for Rotterdam)", the booking clerk said something and I said Ja! As a result of this, I was handed return tickets which swallowed up another tidy sum. I dared not try to rectify the error, besides which I thought it would help to put them off the track. We bought two German newspapers and walked on to the platform. Here it seemed as though the Station master looked at us for longer than was necessary and we were both pleased when the train came in, or rather a train came in. No matter where it was going, we knew that it was heading south, so we jumped in. It is the custom when entering a carriage to say "Good-day", so greeting all my fellow travellers with "Dag!" I sat down, Alex, however, accidentally kicked a man's foot and said "Sorry", so hastily muttering that we were in a non-smoker, I bundled him out and tried again in a coach lower down. I impressed on Alex to keep his mouth sealed no matter what happened and we settled ourselves in corner seats and opened up our papers. All went well until some idiot started conversation and knowing that a remark would be addressed to us sooner or later, I feigned sleep and Alex followed suit. Lucky that we did so because almost immediately an old lady asked Alex a question about the train but seeing us with our eyes closed, turn to someone else.

The train stopped at Utrecht and nearly everyone got out of the train. We dare not ask anything but sat tight and looking out of our window saw several policemen on the platform. No doubt they were looking for us, but we were taking no chances and stuck where we were, no matter where the train went. The train finally reached Amsterdam, where the ticket collector took our tickets without question and told us to get out. Either that hotel proprietor had made a mistake or else we had blundered - we did not know or care. We were well on our road to England, so a few more miles either way didn't matter. As we passed through the barrier, I noticed two mounted policemen who looked at us intently, but we boldly stepped out into the street and made for the Docks. Happening to turn round, I found that we were being followed so we separated and ran for it, agreeing to meet outside the station in one hour's time. Shouts at our rear indicated that our presence was required but this only lent wings to our feet. Diving through dirty backstreets, I found myself in a disreputable neighbourhood but my clothes fitted alright and there was no sign of the police.

After much worry and anxiety I met Alex again and we started to walk along the street. Suddenly I noticed a sign in big letters over a shop - "Bells Asbestos Co." That looked good to me so we went in and asked to see Mr. Bell. I realised later how foolish we were as Bells Asbestos Co. is a vast English concern with branches throughout the world. However, the manager with a smile on his face said "I am Mr. Pearson, can I assist you in any way ?" I nearly shouted with joy to hear English spoken again and nearly threw my arms around his neck. I asked if we might have a word with him and he took us into his private room. There I explained who we were and he appeared to be more than a little worried. Mr Pearson explained that if he were caught helping us, he would be expelled from the country, but at the same time he was very keen to assist us to get home. Locking up his office, he went out and came back presently with two straw hats whereupon he helped to make ourselves a little more presentable and then he took us to the British Consul.

When we arrived there, our reception was just the reverse - the Consul was very agitated and said that we were to get out at once or he would call the police and give us up. I told him what I thought of him, a low skunk I think I called him, and out we went. M Pearson stuck to us and told us to cheer up. He then took us to one of the smartest cafes in Amsterdam. Seated only a few tables away Mr Pearson pointed out one of the Chief Officers in the Police. We were very much more cheerful when we had eaten our meal with the orchestra playing and returned to Mr. Pearson's office. He then informed us that there were no boats leaving Amsterdam and that we must proceed to Rotterdam. He told us to follow him at about five or six paces whilst he walked to the railway station and he would stand alongside the train going to Rotterdam. We were not to take any further notice of him especially if we were arrested. Nothing could be fairer than that. However, I bought two single tickets this time and got into the train without any trouble and we watched Mr. Pearson leave the platform. I had previously promised him to call on his sister in Golders Green if we got back safely, so that she could write and say that she had two sailor boys to tea and he would understand, as all letters were censored.

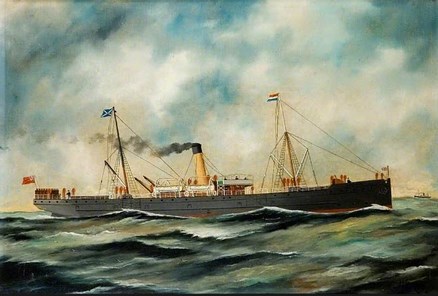

By 6.00 p.m. we were in Rotterdam and with our straw hats on, we pushed through the crowd and caught the first tram passing as our main concern was to get away from the police hanging around the station. As luck would have it, the tram went to the docks but we jumped off before we got there and walked the rest of the way. We found out where the Great Eastern Railway boats went from and on arrival saw three policemen and a sergeant at the entrance to the Quay. How to get past them was a real worry as we knew they were looking for us, when all of a sudden I saw a solitary Dutchman pushing a huge barrow loaded with fruit baskets towards the boat we were anxious to board. Snatching off our straw hats and putting on our caps, we bent down and put our shoulders to the cart, much to the old man's astonishment and delight and he thanked us profusely. He little knew! Straight past the police and right under their noses and alongside the S.S. Cromer. Before you could say 'Jack Robinson', we were up the gangway and dived down below. The skipper wasn't aboard but the crew gave us a wonderful welcome and to celebrate it, I gave nearly all the loose money I had to one of the stokers who went off and return with bottles of beer and gin. When the skipper arrived, he too was very pleased as he received £5 from the Admiralty for every man to took across.

He decided to rig us up as stokers and stripping off our clothes, we went about in vest and trousers, hair ruffled and fairly dirty and I tied a bit of cotton waste around my neck. At midnight, the police boarded the vessel and searched the ship prior to sailing. As they came into the stokehold, the skipper said that he wasn't going to miss the tide and was going to leave and that the Dutchmen could come down the stream with him. However the police did not tarry and went up on deck and gave the skipper his clearance. What a joyous sound it was to us in the stokehold shovelling coal like mad, when we heard the engine bells ring and the ship starting to move. At last we were safe and our troubles over, or at least we thought so. But at dawn we went on deck and at about 9.00 a.m. there was a shout that a German submarine was on our port bow but a good way off. Captain Barton turned the ship around and started to head back to the Hook full steam ahead. Fortunately, after about two hours hard steaming and what seemed like an age to us, we shook off the submarine and again headed for England. At 2.00 p.m. we sighted British destroyers out of Harwich and our skipper signalled information about the submarine. At 3.00 p.m. we entered Harwich feeling terribly excited.