John Duxbury of 'The Miners Battalion'

- Home

- World War I Articles

- John Duxbury of 'The Miners Battalion'

Many local organisations were motivated to assist the war effort. They did this by recruiting men who were associated with the organisation or area, and formed these recruits into battalions. The majority of these battalions were recruited geographically, and such battalions as the Leeds Pals, Bradford Pals and Grimsby Chums were formed. Other battalions were formed not on geographic lines, but by such groups as public schools or those with a common interest such as football.[1]

One of these locally raised battalions was created by The West Yorkshire Coal Owners’ Association. They raised the ‘Miners’ Battalion’ which recruited in significant numbers in the West Riding of Yorkshire. One of the men who joined this unit was John William Duxbury

Above: John William Duxbury

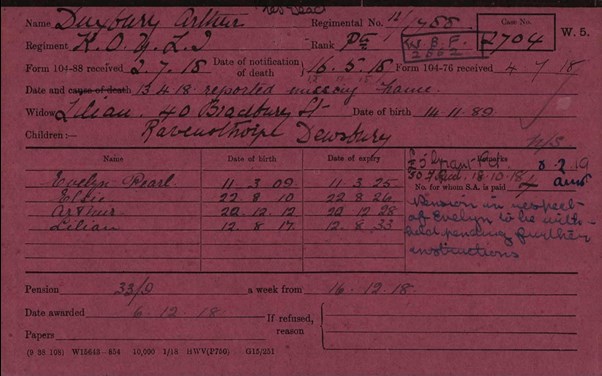

John (aged 26) was probably influenced to join the Miners’ Battalion by his elder brother, Arthur (aged 38) who lived at Bradbury Street, Ravensthorpe. On Tuesday 10th August 1915, they went to the recruiting office in Dewsbury and were given consecutive regimental numbers. Arthur was 1788 and John 1789. Another two brothers also joined the army; Fred aged 22 lived with John and their mother at 76 Sackville Street, Ravensthorpe and joined the 8th Battalion, K.O.Y.L.I. whilst James Duxbury who was married, and aged 28 also joined up but was sent to India.

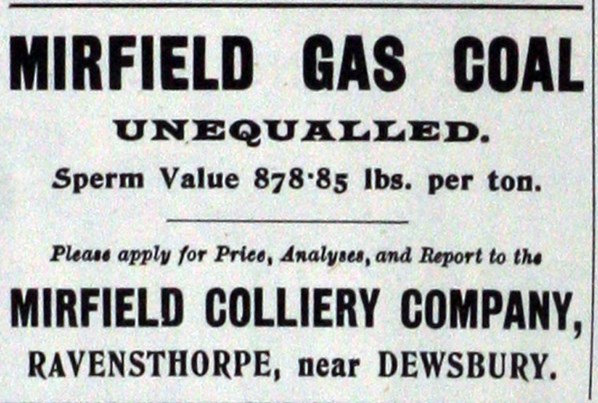

The Miners’ Battalion was clearly open to all trades - whilst Arthur worked for the Mirfield Colliery Company, John was employed by Pickles and Smithson, chemical manufacturers in Ravensthorpe.

Above: A colour postcard showing Ravensthorpe in the early 20th Century

After undergoing training at Otley, the Miners’ Battalion (which had by now become the 12th Battalion, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry) became part of the 31st Division and in view of the obvious labouring skills of the majority of its members, they became the divisional pioneer battalion.

Above: Officers of the 12th KOYLI at Farnely Camp, in 1915

12th KOYLI recruits at Farnley Camp, 1915

Towards the end of November 1915 orders were received to prepare for service overseas.

Much to everyone’s surprise the division was not sent to France, but was instead ordered to Egypt where they were to guard the Suez Canal. After a short period in Egypt, the 31st Division was sent to France where, on 1st July 1916 they took part in the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. The Miners’ Battalion was not heavily engaged in the 1st July attack, although many other battalions from the division were decimated in the unsuccessful attack on the village of Serre. Although the Miners’ Battalion lost 37 men killed on 1st July, both Arthur and John Duxbury came through unscathed; the battalion’s casualties will have been caused as a result of the German shelling of the British trenches, which the Miners had to man after the waves of infantry were either killed or pinned down in No Man’s Land.

One uncanny coincidence which the brothers would undoubtedly have been aware of was the fact that one of the main British trenches behind the front line was called Sackville Street, John’s address in Ravensthorpe!

Despite being wounded in April 1917 (receiving treatment in France), John survived until 1918. In March of that year the Germans launched a series of offensives one of which was aimed at capturing the vital railway junction at Hazebrouck. On 12 April Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig issuing his ‘Backs to the Wall’ exhortation to the troops. It is against this background that John and Arthur Duxbury were involved in the battalion’s severest fighting of the war.

The Miners’ Battalion’s War Diary describes how, in early April 1918, the battalion was out of the line, undergoing training. Orders were received on 10th April, giving instructions to move. On the following day the battalion de-bussed near Vieux-Berquin, and from there marched to Merris. At 8pm orders came through to take up positions astride the Estaires to Caestre road, covering the crossroads in the village of La Couronne. The Miners’ Battalion was in position by 9.30pm.

Above: The area the battalion was ordered to is very flat

On 12th April the battalion was in much the same position; most of the morning was probably spent constructing trenches. The battalion was unable to gain touch with the troops on either their right or their left. At 3pm enemy machine gun and artillery fire became heavy, and troops on the battalion’s left (who, according to the War Diary were from the 29th Division) started falling back. In accordance with its orders the battalion “..refused its left flank, and pivoting on La Couronne covered the village with its right flank facing east and south-east.” They dug in and spent the night there. The War Diary gave casualties for the day as being two officers and 40 other ranks.

The German attack on the following day (Saturday 13th April) developed at 8.30am. The battalion’s left flank easily beat off the attacks by the Germans, all four of which failed. At the crossroads in La Couronne, however, the enemy succeeded in working up a trench that the battalion had constructed, but had been forced to abandon the previous day. From this position, with the aid of trench mortars, the Germans managed to dislodge the defenders who, although forced to fall back formed another line under heavy fire.

The new line faced south-east with its right on a stream; the line extended to the main road where the rest of the battalion was holding off German attacks. Despite now being in touch with the Irish Guards on the right there was a gap here which the Germans exploited and it was from this direction that the battalion was enfiladed at 1.30pm. Shortly after this the Germans, working through the village broke the line. The battalion’s right was forced to fall back, and the troops on the left were partially surrounded, many being taken prisoner.

The remnants of the battalion rallied at La Becque Farm, but machine gun fire made the position untenable, and a further withdrawal was made, falling back on posts held by Australian troops on the Route du Bois.

On the morning of 14th April the Miners’ Battalion was withdrawn from the line. The War Diary describes how, after going into action with nineteen officers and 510 other ranks, the battalion suffered casualties of twelve officers and about 275 other ranks (the CWGC gives fatalities on 13th April as 61, plus a further two on 14th April).

The battalion had, however, accomplished its task, it had delayed the German advance sufficiently to enable troops from the 1st Australian Division to be brought up.

As might be expected, there is no clue in the War Diary of what happened to John and Arthur Duxbury. After sticking closely together throughout the war, on 13th April the brothers’ paths diverged. Arthur was captured, probably wounded, by the Germans; he was, together with other prisoners sent to the rear and eventually arrived in Germany, where, just over a fortnight after being captured, he died.

Above: Pension Record Card for Arthur Duxbury

Above: Pension Record Card for John and Fred Duxbury

Nothing is known of John’s fate. Possibly the family would have realised something was wrong when they failed to receive a regular letter, or possibly an officer or pal may have written to his mother to say that he had not returned after the battle. Although Arthur was reported as missing towards the end of May, it was not until 29th June that the Dewsbury Reporter printed a few lines to say that “Private John William Duxbury, son of Mrs Duxbury of 40 Fearnley Street, Dewsbury is officially reported missing since April.”

Above - nothing remains of Fearnley Street, the properties having been demolished many years ago

Above: A view of West Town, Dewsbury c 1905.

The names of 47 of the 59 men killed on 13th April are inscribed on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing, just across the border in southern Belgium. Of the remaining fourteen casualties from the 13th and 14th April, thirteen have known graves,[2] which leaves one man unaccounted for.

Above: Outtersteene Communal Cemetery Extension

Because of the chaotic circumstances during and after the Great War, it seems that a number of casualties were overlooked by the authorities. It was initially the responsibility of the War Office and not the Imperial War Graves Commission to compile lists of casualties. Somehow the name of John William Duxbury failed to be included in the lists the Imperial War Graves Commission took over from the War Office, and consequently his name was not inscribed on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing. For nearly eighty years, John Duxbury was not officially commemorated by the War Graves Commission.

This oversight was pointed out to the Commission, and after requesting evidence in November 1995, they confirmed (ironically on 14th April 1997, 79 years and one day after his death) that John William Duxbury’s name had been added to the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing.

Above: Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing

John’s older brother, Arthur, is buried along with several hundred men who died as prisoners of war in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission plot in Ohlsdorf Cemetery near Hamburg.

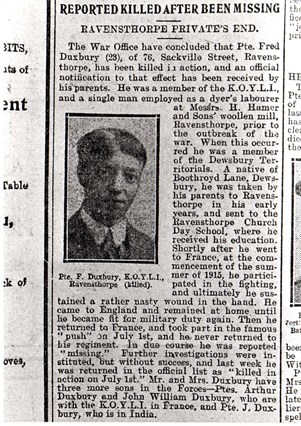

Fred Duxbury was one of the casualties of 1st July 1916, he died whilst serving in the 8th Battalion, K.O.Y.L.I. and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

Above: Dewsbury Reporter obituary to Fred Duxbury

Only James Duxbury came home.

Article by David Tattersfield Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

[1] The 16th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment and 18th to 21st Battalions, Royal Fusiliers were the ‘Public Schools’ Battalions and the 17th and 23rd Battalions, Middlesex Regiment were subtitled the 1st and 2nd Football Battalions.

[2] One is buried at Ebblinghem Military Cemetery, one at Aire Communal Cemetery and one at Longuenesse (St. Omer) Souvenir Cemetery. A further ten are buried at Outtersteene Communal Cemetery Extension, being two miles north-east of where the battalion fought on 13th April. (It may be fair to assume that some of the unknown headstones in this cemetery stand over the graves of the 47 men named on the Ploegsteert Memorial.)