Memories of the child of an Imperial War Graves Gardener

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Memories of the child of an Imperial War Graves Gardener

In November 1999, a WFA member called Frank Burns of Scruton, Yorkshire, was invited to address a local branch of Probus on the subject of ‘Visiting the Battlefields of the First World War’. Enjoying a coffee before the meeting began, he was approached by a man carrying a plastic bag containing old photographs and newspaper cuttings. The man was called John Gabriel and he and his family had lived in Ypres until the outbreak of the Second World War, when they had been forced to flee the advancing German Army. John was 14-years-old at the time and his father a gardener with the Imperial War Graves Commission. This is his story...

‘My father Hubert (known, of course, as “Bert”) Gabriel was a gardener in Kent before the First World War. On the outbreak of war in 1914, my father volunteered for service with the Royal West Kent Regiment. He was in a Yeomanry unit, but I don't know which one.

‘My father said very little about his war service other than he worked with the horses moving up materials and ammunition. He was in the Ypres sector but he never mentioned any other area of the Front. I don't know if he was ever in an infantry attack. He was a very lucky man because the only wound he had was from some rusty barbed wire.

‘After the war he returned to service as a gardener in Kent, but soon heard that the Imperial War Graves Commission was seeking gardeners to set-up the work in the cemeteries. He was accepted and returned to Belgium. In the beginning the cemeteries were just bare earth with wooden grave markers and a wire fence enclosing the area.

Sunday afternoon in the Grand Place, Ypres, in the 1930s. Bert Gabriel is seated on the extreme right and John can be seen peeping out on the far left. John's mother is seated next to his father.

‘I don't know where all the plants came from to furbish the cemeteries but I guess that they came from England. Father often took me to work. I had a little seat on the crossbar of his bicycle and he pedalled along the flat road from our house on the Menin Road to Bedford House Cemetery. It was at Bedford House Cemetery that my father had to report to be allocated the day's work. He often worked at Bedford House but also at Oak Dump and Chester Farm cemeteries. He took me there most days before I started school, often with a friend. It was a wonderful experience in my formative years being deep in the countryside close to nature. I can still remember the richness of the bird song, particularly the yellowhammers.

‘Father was a keen cricketer and he joined one of the teams of IWGC gardeners which flourished in and around Ypres in the 1920s and 30s. I went to the British School in Ypres – St George's Memorial School - next to St George's Memorial Church. There were many British families in the area and there were four classes with over 30 children in each. Our teachers were from England, as I remember. They stayed for four years before returning to England. There was a rota so that they did not all return the same year. The atmosphere was very British; Empire Day was commemorated in style. The school had a good-sized playground and we played rounders and table-tennis when it was fine.

A battlefield tour party of former Royal West Kens remember one of their fallen chums at a grave in the Ypres Salient in the 1930s. Bert Gabriel can be seen at the far back

‘We were not taught Flemish or French at school but I was reasonably fluent in those languages. I could talk to the locals, ask directions, ask the time, etc. Father was quite fluent but the problem for him was that most of the people he met wanted to practise their English.

‘In the holidays and after school we enjoyed a very free existence. There were no controls on where you could go to play. We had bicycles and scooters and rode along the roads into Ypres, or even as far as Kemmel. Ruined dugouts and trenches were there to play in, as were the ramparts of the town. As I recall, there were no warning notices or ‘Keep Out' signs and I don't remember seeing shells or grenades lying about.

John Gabriel and his father, Bert, on the steps of a rotunda at Bedford House Cemetery in the 1930s.

‘I expect that by the time I was playing with my friends, salvage teams had scoured the land for all metal objects. We could, though, climb down into dugouts and scramble about inside. One incident I remember vividly was my father finding a shell and taking it on his bike to a scrap-metal dealer. When we got there, the shell was pronounced live. Everyone scampered like lightning. My friends and I earned a little pocket-money finding lead shrapnel-balls when the farmers were ploughing.

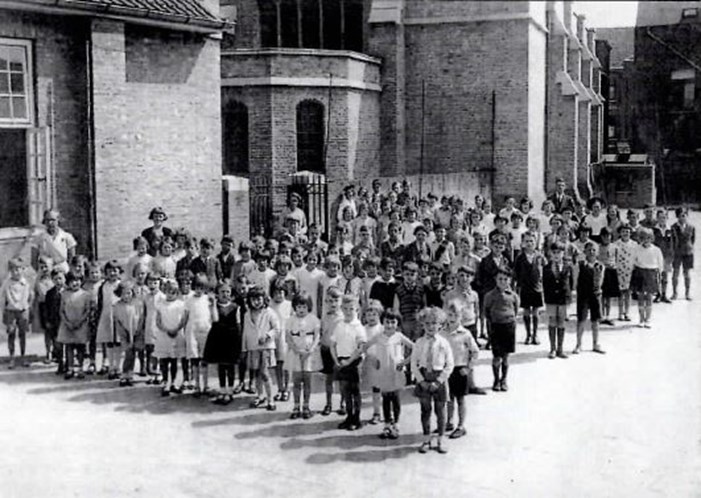

A photograph of all the schoolchildren at St George's Memorial School, Ypres, taken circa 1932. John Gabriel was in the infant class and can be seen on the extreme left of the front row.

John Gabriel and friends at play in an IWGC wheelbarrow circa 1932.

‘When the German Army invaded Belgium on 10th May 1940, an increasing flow of refugees began to arrive in Ypres. All teaching at the school ceased and the building became a refuge for the people and the kitchen supplied their meals. The speed of the German Army's advance took everyone by surprise. We were not thinking of leaving but we were told that the Germans were closing in and we had to leave in an hour. Imagine today being told to leave at an hour’s notice, get a suitcase and put your most valuable things inside, bang the front door and leave!

Germans at the Menin Gate, circa 1940

‘This is what we had to do. Fortunately, my father (who had been helping to organise tour parties to the battlefields) had friends in the local tourist industry. One, a taxi driver, was persuaded to take my mother and me and the school-teachers to Ostend. I have vivid memories of thousands of refugees, Allied troops, cars, military vehicles crowding the road. We made it to Ostend and spent the night there, raided by German bombers. We got on the last ferry for England.

‘Father was instructed to stay behind - goodness knows why as there was no work being done. It was chaos. We didn't know what had happened to him and he didn't know what had happened to us. We were staying with an aunt in Kent and about a fortnight had elapsed when ‘out of the blue' my father walked in. We were, of course, delighted to see him and, after our excitement had calmed down a little, he told us of his escape from Belgium.

‘As the German Army closed in, Dad left Ypres and started to cycle towards the coast In civilian clothes and, of course, speaking English, a British Army unit stopped him.

‘They were very suspicious (there was lots of talk of ‘fifth columnists' and spies). They arrested him and confined him to a tent as they thought that he was a spy. They probably didn't know what to do with him so they took him with them and he ended up at Dunkirk. He came across on a destroyer with the unit and that's how he got back home.

‘Dad got a job working as a gardener in Battersea Park in London. He got this job through meeting a Mr Little, a man who he knew from the battlefield visits made by his old regiment. Mr Little worked for the musical-instrument makers Boosey & Hawkes They needed a caretaker/gardener and Dad accepted the job.

‘When the war ended, Dad decided not to return to Ypres. Lots of his former colleagues did, however, decide to return to begin the restoration of the war cemeteries after five years of neglect. Dad did go back to try to see if he could salvage anything from our former home. I don't know what happened to the house during the occupation and Dad found nothing to bring back except a clock presented to him for his services to the British Legion in Ypres. He had called in the office of the Imperial War Graves Commission where he made himself known and there, on a mantelpiece in the offices, he saw his clock. He was absolutely delighted. No one knew how it had got there but it now stands on my mantelpiece.

‘I remember the great Armistice Day ceremonies at the Menin Gate in the 1930 and the Last Post being sounded every night at 8pm. I walked to school through the Menin Gate. It has wonderful memories for me.

‘I returned to Ypres in 1998, almost 60 years after we had left. My wife and I went on a tour organised by the Holy Cross Church in Greenford, Middlesex. It was a fantastic experience visiting all the places which were familiar to me even after 60 years.

‘We stayed in Ypres and did the usual tour route: Hill 60, Sanctuary Wood, Tyne Cot, Langemark and, of course, the Menin Gate. We also visited cemeteries where I had helped my father and where I had played as a boy.

‘We looked for our first house in Ypres on the Menin Road, but we couldn't find it. We went to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission offices and I told them who I was and that I was trying to find our second house where we lived until our escape. I remembered it being near a place called the `plaine du moor'. As I remembered it, it was a vast open area of waste ground. It is now a sports complex and they directed us to it. Near the sports complex was the little house where we used to live - just as I remembered it. We took photographs and marvelled that it had not changed in any way.

‘We visited Shops owned by the same families I remembered from 1940. When I said that I could remember their parents they were amazed. We visited a photographic shop called Daniel. I have photographs from the 1930s with their trademark on them. They showed me old pictures of Ypres and I showed them mine. I thought that would close the story – but then Frank Burns came along to our Probus meeting...’

Edited by Dr Martin Purdy