Memories of Verdun by Francois Wikart

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Memories of Verdun by Francois Wikart

The following article is based on the recollections of General Caloni and recollections of the authors’ grandfather’s experience of Verdun.

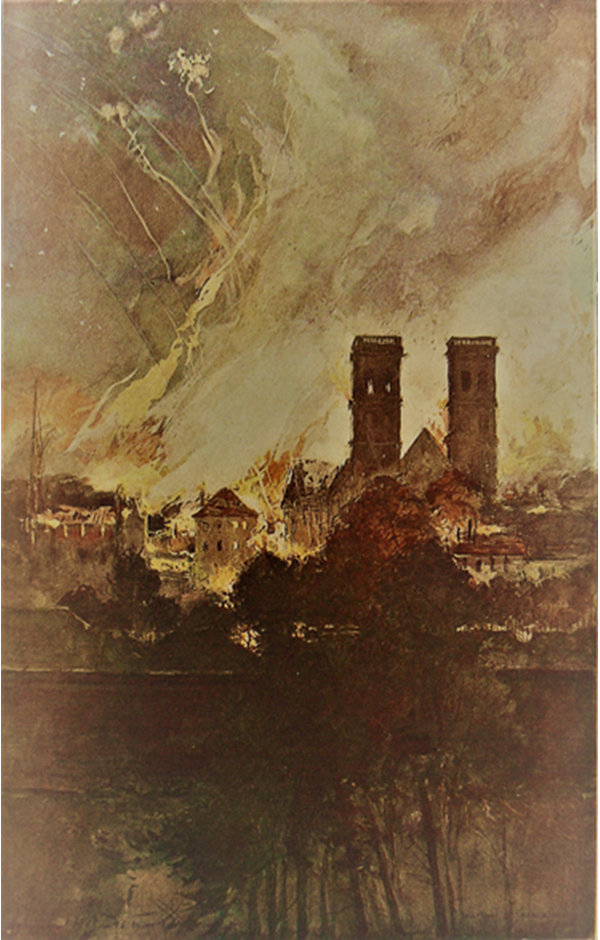

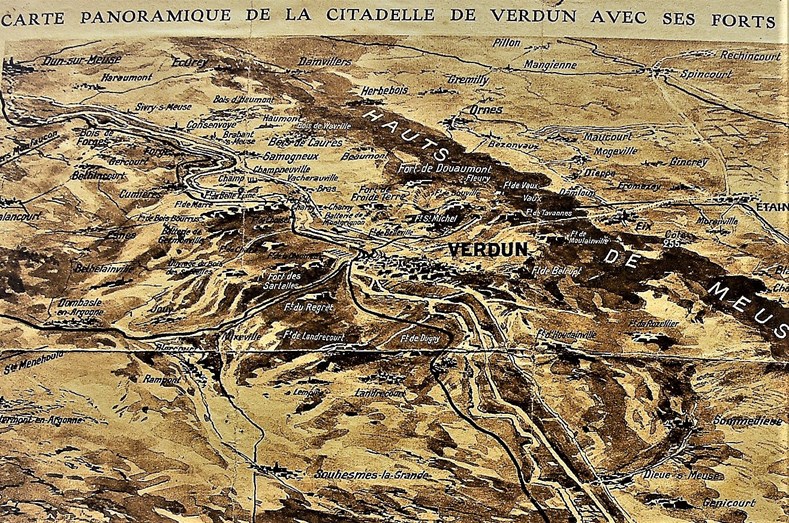

Most people know the battle of Verdun started on the 21st February 1916. The city lies on both banks of the River Meuse in North-eastern France.

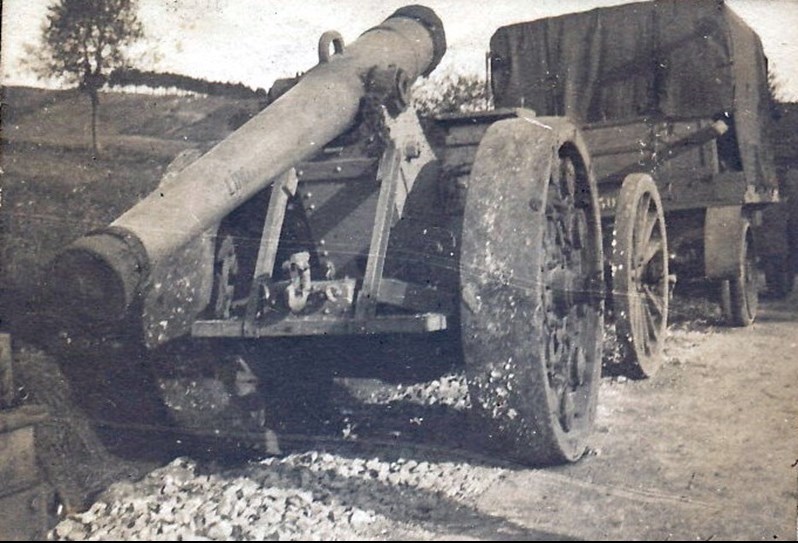

In 1916 the fortress of Verdun was stripped of its guns and the forts manned only by token crews. GHQ had decided after the rapid fall of the Belgian forts in 1914 and the great need of artillery for the French army in the field that forts were of no great use. This made Verdun an almost ideal target even more so because the trenches there were in a poor state or in some cases non-existent.

Verdun was the longest battle of the First World War running from February to December 1916 – a total of 10 months.

The battle can be divided into four phases.

|

1 |

21 February 1916 |

Initial Onslaught |

|

2 |

March-April 1916 |

Attack on the Flanks |

|

3 |

May - September 1916 |

War of Attrition |

|

4 |

October - December 1916. |

French counter attacks |

The whole battle was an unprecedented slaughter. Statistics differ as usual but we can reckon for both sides on at least a total of 714,000 losses (killed, wounded and missing). 377, 000 French; 337, 000 Germans

German Field marshal Hindenburg recognised this fact in his memoirs 'this battle exhausted our forces like a wound that wouldn’t heal'.

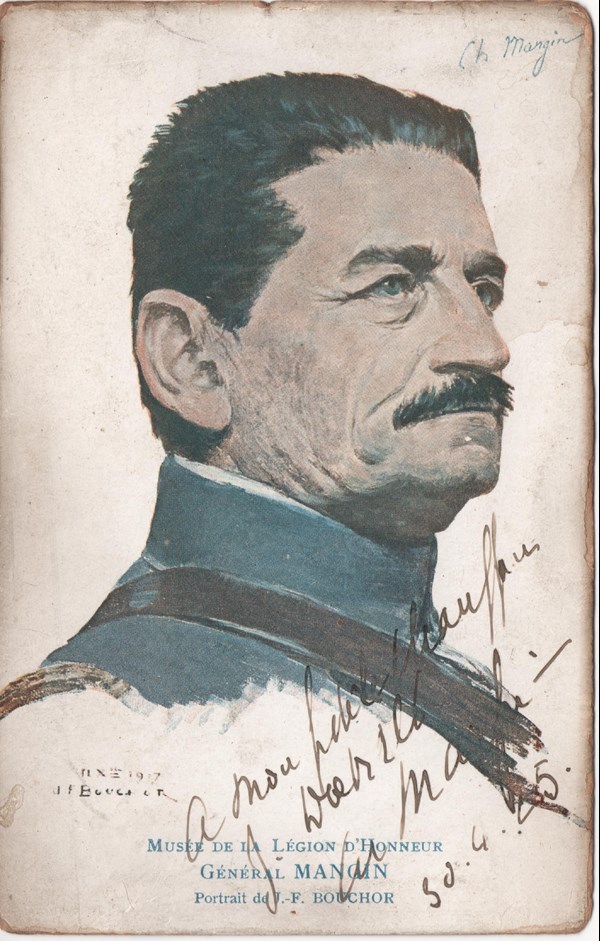

I have chosen two lesser known stories to illustrate this battle. Both showing the work of the engineer corps. They are taken from a lecture given by General de Division (major general) Jean François Caloni from the engineer corps on the 25th December 1925 at the Sorbonne University. General Caloni commanded the engineers of the Mangin Army group from June till December 1916; that is to say the eastern part of the battlefield.

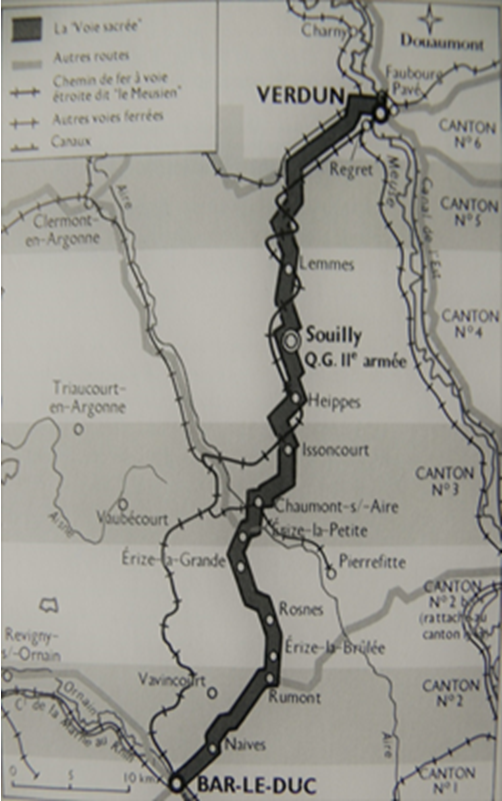

And I finish with the creation and maintenance of the main artery feeding the battle field, the road going from Bar le Duc to Verdun now known to all as the 'Voie Sacrée'.

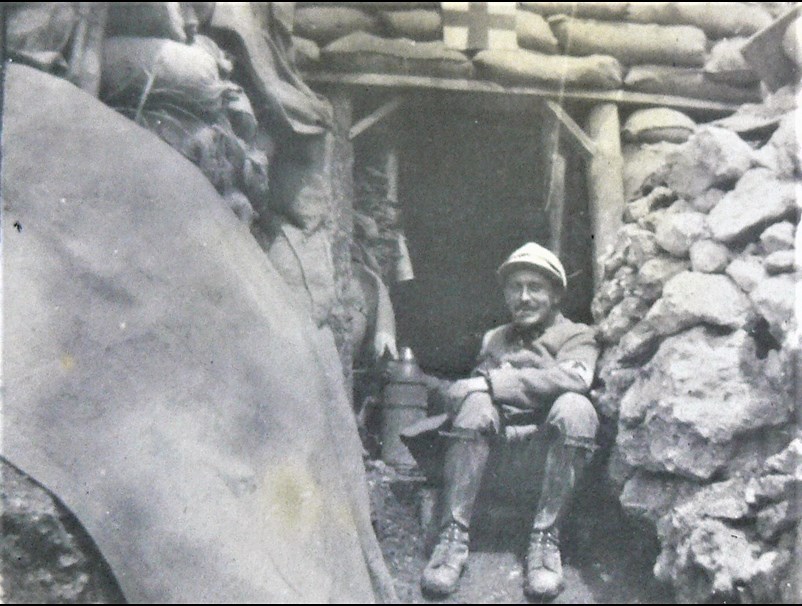

The front line of trenches were dug by the divisional troops when there was a lull in the battle. A second position was being created between Froideterre*and the slopes at the back of Fort Souville.

The engineers of the army corps had two companies of pioneers and several battalions of territorials that were in charge of this second position. Every evening the officers of the pioneer companies came up to the line to prepare the work for the following day. Every evening guides from those companies arrived to pick up the battalions coming from Verdun and led them to the working site. Work lasted the whole night. At dawn troops returned to their barracks. One can imagine the difficulty of working under constant bombardment and often in the middle of clouds of gas being sent over from the German lines. Nevertheless our French territorial troops carried on and got the job done.

The River Meuse skirted the rear of the battlefield and it would have been a pity not to use a navigable river and its canal. So from the very start of the battle shipping was organised.

We shipped an average of 50 tons of ammunition per day. It was an important effort that helped the artillery.

We started with shipping ammunition. Supplies were loaded upstream of Verdun and carried by barges near the batteries located alongside the River Meuse. They were unloaded and passed on to the gunners who in turn passed back the empty shells.

We also organised the transportation of the sick and wounded from the area of Bras who were initially attended to in a first aid post near la Folie.

We also organised the transportation of the sick and wounded from the area of Bras who were initially attended to in a first aid* post near la Folie.

To evacuate them by road was arduous and dangerous; during daylight it was impossible and at night it was rather difficult as the roads were watched by the German and shelling made them impassable.

This mode of transport worked perfectly well during the whole of the battle. We never had any casualties. The only incident was created when a shell exploded near a barge opening a hole in the hull. The barge started to sink but thanks to our pontoniers the wounded were safely transferred onto another boat.

In addition to these works we had to maintain the roads between the Meuse River and the front lines. Up to the Meuse the maintenance was the job of the Army. From the Meuse up to the front line the engineers of the army corps were in charge. All the roads were inspected and repaired according to needs. I can’t say that the roads were like the avenues of the Bois de Boulogne but we had serviceable roads.

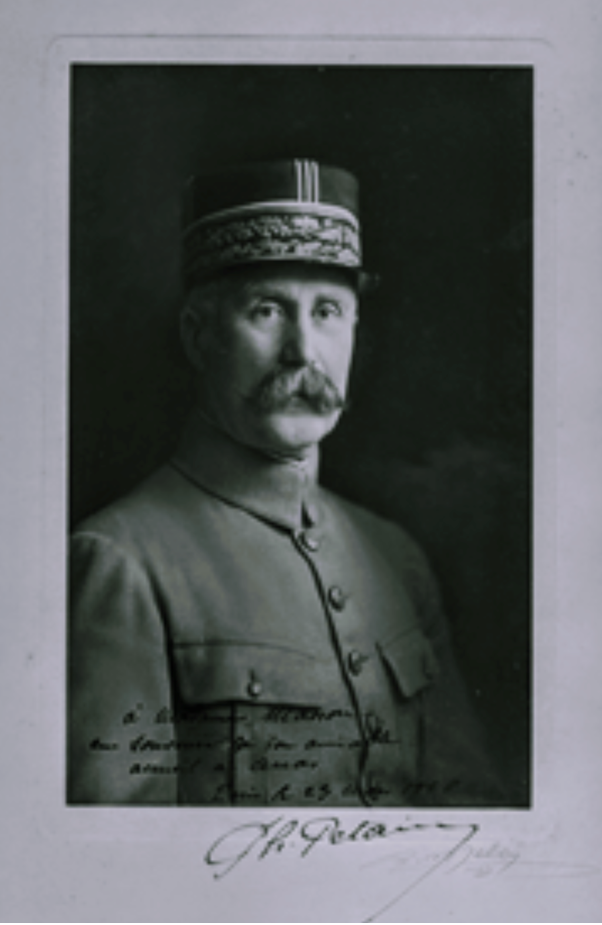

Général Pétain was in command of II army the army of Verdun and then later on in command of army group centre still including Verdun.

20 July - 20th September

This period saw the reorganisation of the sector and its reinforcement. We dug communication trenches, deepened the front line trenches* and improved the roads going to Belleville and Saint Michel ridge. We couldn’t work any further as we were in full view of the Douaumont observatory, held by the Germans. During the day it was impossible to show ourselves further forward than the front line at Saint-Michel without being shelled.

The terrain made the organisation of the front lines very difficult, the terrain being churned up, the ground collapsing beneath our feet and springs appearing on the highest points. Water was everywhere on the ridges. In many places it was difficult to dig trenches and it was impossible to lay barbed wire networks in front of the trenches. There additional defences were made of improvised structures from barbed wire on light trestles that were thrown in shell craters. These were called hedgehogs or Easters eggs. Above those improvised structures and portable wire entanglements we were throwing lengths of 3, 6, 8, 10 m of barbed wire. These intermingled lengths of barbed wire pinned to the ground with huge nails called “queue de cochon” were extremely useful obstacles.

La Voie Sacrée

There were only two means of access to Verdun: the narrow gauge railroad known as the Petit Meusien,* served as a transportation link for food supplies and some military materiel; and the road from Bar-le-Duc for troops and trucks. This road was later to go down in history as the Voie Sacrée. General Pétain* took charge of this road and turned it into a lifeline between the front and the supply depots in the rear.

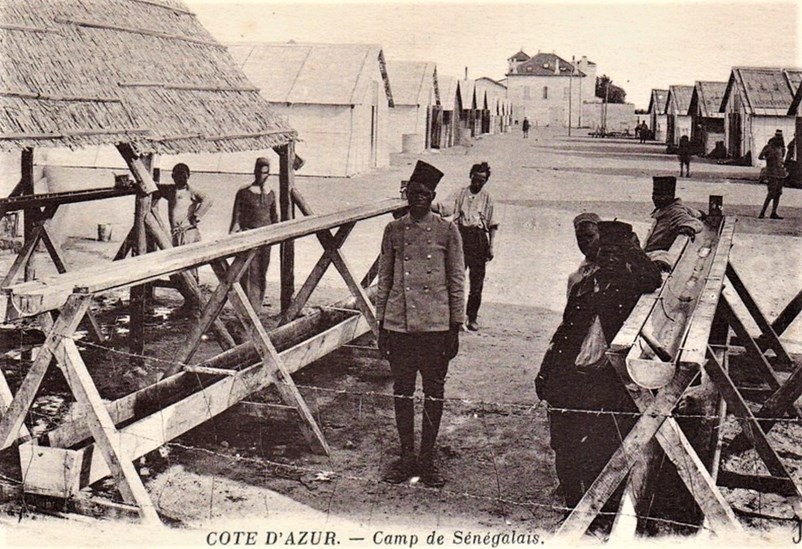

Senegalese troops were volunteers who couldn’t cope with the bad winter weather of the eastern part of France they were sent to the ‘Côte d’Azur in southern France.

Thirteen battalions of Senegalese territorials were pressed into service as a road maintenance crew.

Nearby stone quarries were reopened and a steady stream of stones from them spread 24-hours per day under the wheels of the trucks, which acted as steam rollers filling the ruts in the road. An endless line of convoys drove over the road to Verdun day and night. It was called the 'Noria': every week, 90 000 men and 500 000 tons of materiel were carried over the road by 35 000 trucks, plus every other known type of vehicle — Paris buses, private cars, etc. Appropriate goods were delivered for every corps: engineer, artillery, aviation, radiotelegraph, postal, photography.

By July 1st, 65 out of the total 95 French infantry divisions had passed over the Voie Sacrée via the Noria System, up to the front lines and back again.

Toward the end of 1916 the German army confronted by the onslaught of the allied armies on the Somme since the 1st of July, having had huge losses at Verdun and lost the supremacy in the artillery duel were pushed back by several counter offensives.

Counter Offensives made possible by the reinforcements Pétain had obtained at a cost from Joffre. In doing so he had annoyed him tremendously so Joffre decided to get rid of him by the usual mean of a promotion as he could not dismiss the saviour of Verdun.

Pétain was given the command of army group centre in charge of the central part of the French western front including Verdun.

Thanks to these reinforcements and a close control of general Nivelle in command of 2nd army and Mangin 5th Infantry division on the 22nd of October Douaumont the main fort of the fortified defence of Verdun was retaken. In November it was Fort Vaux.

This ‘fait d’arme’ unluckily would in 1917 turn into a pyrrhic victory.

In Memoriam

To my grandfather: Raymond Gohierre de Longchamps, a Major in the 28 RIT who commanded the Fort of Souville in April 1916 who told me my first stories about Verdun.

Francois Wicart (2020)

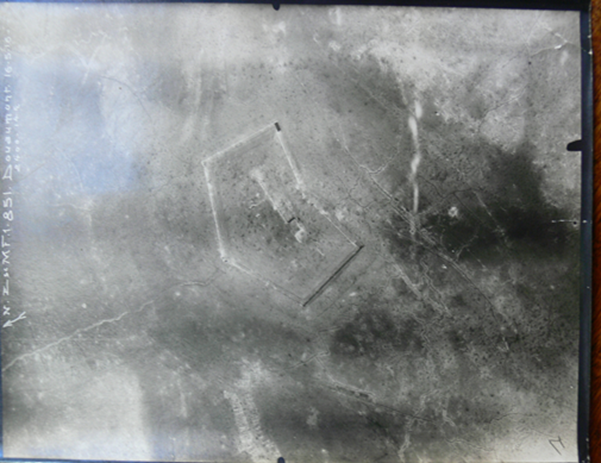

All photographs are from a private, unpublished photo album © Francois Wicart : Private Collection