SS Laurentic: A story of Gold Bullion, Crime and Intrigue and loss of life that helped change the course of WW1.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- SS Laurentic: A story of Gold Bullion, Crime and Intrigue and loss of life that helped change the course of WW1.

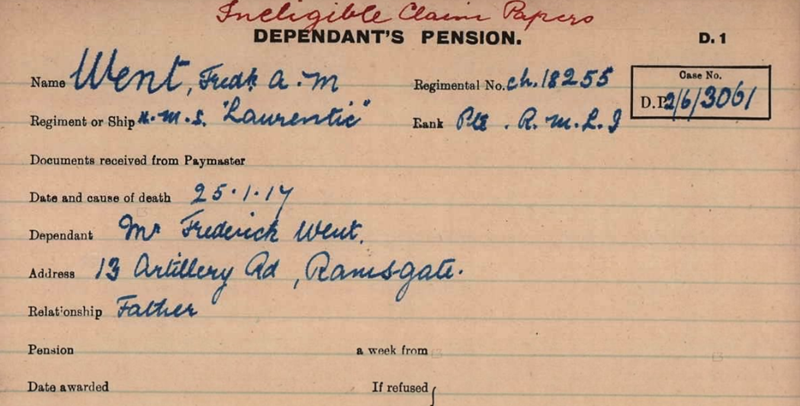

This story begins with an ordinary Pension Card that relates to a 20 year old Royal Marine named Frederick Went.

Frederick Arthur Moat Went (CH/18255) served with the Royal Marine Light Infantry on H.M.S. 'Laurentic'. He lost his life on 25 January 1917 when his ship sank. He was the son of Frederick and Eliza Went and is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial. At first there is nothing remarkable about him as he perished along with 354 others after Laurentic struck two mines off the coast of Buncrana which is located on the eastern shore of Lough Swilly in north County Donegal.

However the SS Laurentic had history and as such is worthy of some research.

The Laurentic was a British ocean liner of the White Star Line and was built in the same shipyard as the Titanic (Harland & Wolff, Belfast 1908). At the onset of World War I she had been converted to an armed merchant cruiser. However before her sinking the Laurentic was famous for more reasons than her tragic loss of life in 1917. The ship had a history of intrigue and mystery that is just as captivating as the story of its demise is tragic.

SS Laurentic was a ship built for speed: at 570 feet long, she could outrun any German U-boat of the era, with a speed of up to 17 knots.

However before the British Admiralty commissioned the ship to join the war effort, she was also associated with a famous moment in history: the capture of the suspected murderer, Doctor Crippen.

Dr Crippen was an American doctor who murdered his wife, Corrine 'Cora' Turner a music hall singer (known as Belle Elmore) following a party at their home in Holloway, London.

The Crippens often took in lodgers to augment Crippen's meagre income and Cora had an affair with one of these lodgers. In 1908 as the story goes, he drugged then butchered his wife Cora, and buried her remains in the cellar. Shortly after, he openly began having a relationship with his mistress, Ethel Clara Neave telling police that his wife had left him to go to America, and had later died there. With detectives asking questions, he fled to Belgium, and went into hiding. As the net closed, he and his mistress (Ethel) boarded a ship called the Montrose in disguise, bound for Canada. Detectives on his trail quickly realised he had fled again, and with the Montrose three days ahead of them, they boarded the much faster SS Laurentic to give chase. They arrived in Quebec three days ahead of him, and waited for the Montrose to arrive. He was arrested and returned to London, where he was later hanged in Pentonville Prison in London on the 23 November 1910. Ethel Neve was exonerated of the charge of complicity to murder. In January 1915 she married Stanley Smith, with whom she had two children and died in Croydon 1967.

Up until the outbreak of war Laurentic was in regular service from Liverpool to Canada and in 1912 passed near where Titanic had sunk a few days earlier. However in 1914 because of her speed Laurentic converted to an armed merchant cruiser (AMC) and was fitted with eight 6-inch and two 6-pounder naval guns. As an armed troop ship Laurentic saw service in the Kamerun Campaign, and also the African theatre. In August 1915 she was deployed on patrol around Singapore, Rangoon, and Hong Kong but by June 1916 she had left Asia and spent the following months patrolling near Halifax and carrying Royal Canadian Navy officers and ratings for the Canadian Volunteer Reserve.

In 1917 as the war began its third year the Kaiser met with Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and his military leaders to discuss measures to resolve Germany's increasingly grim war situation; its military campaign in France had become bogged down, and with Allied divisions outnumbering the German by 190 to 150, there was a real possibility of a successful Allied offensive. Meanwhile, the German Navy remained bottled up in its home port of Kiel, with the British blockade causing food shortages and malnutrition in Germany causing widespread unrest. The military staff urged the Kaiser to unleash the submarine fleet on shipping travelling to Britain with Hindenburg advising the Kaiser that "The war must be brought to an end by whatever means as soon as possible"

On 31 January, the Kaiser duly signed the order for unrestricted submarine warfare to resume on 1 February 1917. At that time Germany had 105 submarines ready for action: 46 in the High Seas Fleet; 23 in Flanders; 23 in the Mediterranean; 10 in the Baltic; and 3 at Constantinople. Fresh construction ensured that, despite losses, at least 120 submarines would be available for the rest of 1917. The change in tactics was initially a great success with some 500,000 tons of shipping being sunk in both February and March, and 860,000 tons in April, when Britain's supplies of wheat shrank to six weeks worth. In May losses exceeded 600,000 tons, and in June 700,000. Germany had lost only nine submarines in the first three months of the campaign. Although concerned the U.S. might react by intervening in the war, German military leaders calculated they could defeat the allies before the U.S. could mobilize and arm troops to land in Europe. However the calculation backfired and in response to the new submarine campaign, President Wilson severed all diplomatic relations with Germany, and the US Congress declared war on 6 April 1917.

It is now that the Laurentic comes back into focus and takes up another role in intrigue and mystery.

On 24 January 1917 Captain Reginald Norton was ready to leave Liverpool cargo and passengers safely onboard. All that was required were sailing orders. It was common practice for the British Admiralty to issue final directions on the day off departure as a precaution against German intelligence. There were two routes that the Laurentic could take: a route south of Ireland (Code E-F-G) or a northern route ( R-S-T). At 11.30 a.m. Norton received code R-S-T which meant he would sail the northern route hugging the coast of Ireland before reaching the open Atlantic and Halifax, Nova Scotia. Laurentic left Liverpool at 3.00p.m.

What was unknown to the 479 passengers, mostly naval officers, ratings, and Volunteer Reserves, was that she was also carrying a secret cargo of gold which was to be used for the purchase of war munitions from Canada and the United States, or used as collateral for war loans. The gold (44 tons) was in the form of 3211 individually stamped and weighed ingots. The ingots had been packed into wooden boxes and stowed in the second Class baggage room. The total value of the gold cargo in 1917 was approx. £5,000,000. (£231,468,000 in 2020)

Having left Liverpool on the 25 January the ship made an unscheduled stop at the naval base in Buncrana, Ireland, to allow four ratings to disembark; Seaman G. Ford, Maidement, G. Pike and C Lomerton who were suspected of having contracted ‘spotted fever’ whilst at Chatham Barracks . Officers on board took the short opportunity of a brief 'shore leave' and enjoyed a meal at the local Swilly Hotel, before setting back off to sea. The ship lifted anchor around sunset, moving toward Fanad Head, where she was to meet with a destroyer escort. The weather was bitterly cold and a force 12 snow storm battered the ship. Blizzard conditions badly affected visibility, but Captain Norton gave the order to proceed without the escort, despite reports that a German U-boat had been spotted in the area earlier.

Less than an hour after leaving Buncrana, the ship struck two mines laid by the German mine-laying submarine U-80 off Lough Swilly. One of the mines exploded near the engine room, which left the ship without power causing it to list at 20 degrees; the combination of the darkness, list and loss of power made it difficult to lower the lifeboats, and impossible for the ship to issue a distress call. It was pitch black, and while the Captain evacuated as many as possible, the crew were basically on their own. The storm continued, meaning no land-based rescues could be launched. Many aboard the lifeboats died from exposure in the freezing conditions. The ship sank within an hour.

Those who made it onto lifeboats faced extreme cold as low as −13 °C (9 °F). Survivors rowed towards Fanad Lighthouse, and some were rescued by local fishing trawlers. In the morning, many were found frozen to death in their lifeboats, with their hands still gripping the oars. The official count lists 475 passengers on board at the time of sinking, meaning that only 121 survived, and 354 were lost in the disaster. Perhaps the 4 disembarked ratings were the lucky ones with hindsight as spotted fever must be better than the risk of drowning.

On 1 February, The New York Times reported that the last person to leave the ship was Captain Norton, who survived. He was quoted as saying: "To the best of my knowledge, all the men got safely into the boats. The best of order prevailed after the explosion. The officers and men lived up to the best traditions of the navy...The deaths were all due to exposure, owing to the coldness of the night. My own boat was almost full of water when we were picked up by a trawler the next morning, but all the men in the boat survived. Another boat, picked up at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, contained five survivors and fifteen frozen bodies. They had been exposed to the bitter cold for over twenty hours."

The following day, the Swilly Hotel where officers had dined the night before, was converted into a makeshift morgue for the casualties. Many bodies were trapped below the lower decks as the ship sank, and were washed up for weeks afterwards. Some 65 victims of the tragedy are buried at St Mura's Church in Fahan, as well as Cockhill graveyard in Buncrana.

Beyond the tragedy, the intrigue with the ship continues today. Shortly after the sinking, the Royal Navy launched a recovery operation to retrieve the gold that the Laurentic was carrying.

Thus began an operation which lasted two years, and while virtually all of the gold bars were recovered, 25 still remain on board the ship, or somewhere near the wreck valued today at about £3 million.

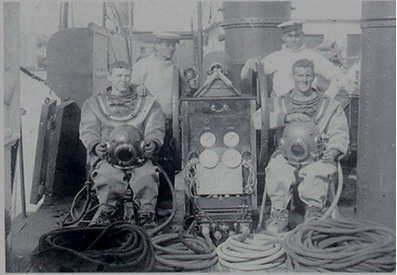

The Government was of course desperate to retrieve this vast some of money if possible and so a team of Royal Navy salvage divers led by Commander Guybon Chesney Castell Damant C.B.E., was assembled. Damant, a famed Navy diver, who was told by the Admiralty he could have as many other divers as he wanted and to start work immediately. The recovery of the Laurentic gold was to be his top priority. As a result he called in another well known Navy diver, Dusty Miller, and the rest of the so called 'Tin Openers', so called for their work penetrating sunken U-boats. It was the ‘tin openers’ who were to prise the gold ingots from the wreck. They were told to do it as quickly as possible as the British Government feared that aid from America would dry up if there was no gold to back up the buying power of the British pound. Also among the team the divers chosen was Petty Officer Augustus Dent. He had served on board the Laurentic as a gunner’s assistant and ship’s diver and had survived the sinking and now within months was back to help recover the gold.

The detail of the diving salvage is well documented in two books.[1] Between 1917 and 1924, Damant and his team had made over 5,000 dives to the wreck recovering all but 25 of the ingots. Each diver got a bonus of two shillings and sixpence for every £100 raised. Other salvage operations in 1930 recovered three more bars of gold. In July 1987 another operation, using bell divers, failed to find any of the other 22 bars, which are now said to be worth some £2million. The last of the gold recovered by the Royal Navy was some 10 metres (33.8 feet) under the sea bed, thus the remaining gold may be difficult to reach.

The wreck lies about 40 metres (130 ft) beneath the surface, and its salvage rights are privately owned but much more importantly for Frederick Went and his crew mates and passengers it is an official war grave under international law.

The recovery of the Laurentic's gold is to this day the largest recovery, in weight, of a sunken gold hoard. As well as his salvaging exploits, Lt Cmdr Damant also led a team of covert divers to search through the contents of sunken U-boats for cipher keys, signal books, minefield schematics and other secrets. They obtained items from at least 15 different U-boats which were shipped off to London to be analysed by the intelligence services. The information gleaned from these recoveries were crucial in Allied efforts to defeat the U-boats and win the war.

So from one Pension Card of Frederick Went as part of the WFA Project Home Town comes a story that I’m sure he would never have imagined when he enlist to serve on the SS Laurentic.

Addendum

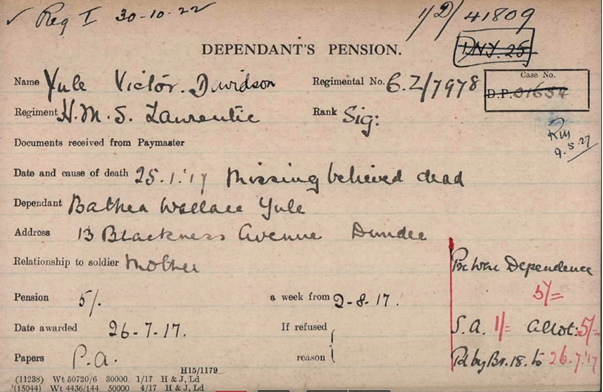

Victor Yule (19 yrs old) is one of the 256 seamen of the Laurentic who lost their lives and were later recovered and buried or commemorated on the memorial within the churchyard, at St Mura’s Parish Church, Fahan. County Donegal

Lieutenant William A McNeil is buried at Heisker 150 miles away in the Monach Islands.

[1]The Sunken Gold by Joseph A Williams and We Own Laurentic by Jack Scoltock & Ray Cossum.

Article by Robert Stone