The Aristocrats' Cemetery at Zillebeke

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Aristocrats' Cemetery at Zillebeke

(This article is taken from Stand To! No 90, published Dec 2010/January 2011. You can receive copies of Stand To! by becoming a member of the WFA.)

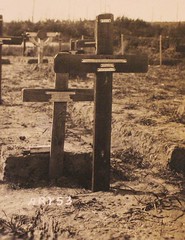

The author's first visit to the Zillebeke Churchyard Cemetery came about almost by accident. He was driving through the village in February 2006 when his attention was drawn to a small cluster of Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) headstones in the churchyard. After a closer inspection of the dates on the headstones it quickly became apparent that the churchyard was the final resting place of seventeen officers and men who had been part of the original British Expeditionary Force of 1914 and who had fought in the First Battle of Ypres. There are thirty-six CWGC headstones in the churchyard of which twenty-six are identified. Of these, all but seven are men who were killed in 1914. The resulting research into these men which unearthed a huge archive of personal diaries and letters led to the writing of a recently published book ‘Aristocrats Go to War - Uncovering the Zillebeke Churchyard Cemetery'.

Not long ago I was asked what the officer corps of the British Army of 1914 was like and whether I thought the men in it were of a different calibre to those that followed them in the New Armies. The answer lies in the Zillebeke Churchyard Cemetery, for in this secluded spot a typical cross-section of the men who sailed for France in the early months of the war and fought the 1914 battles found their last resting place. There is no doubt that they were men of a different character and disposition to those who followed; they were part of the last legions of Edwardian gentlemen: chivalrous, privileged and stubbornly proud of their traditions. Above all, they epitomised the professional British soldier of 1914, earning the devotion of their men and the respect of their opponents in equal measure and as an officer class we shall certainly never see their like again. But as to calibre, I believe there was little difference between them and those who came afterwards. Bravery, duty and loyalty were part of the standard that had been set by the professional soldier of 1914 at Mons, Le Cateau, the Aisne and First Ypres - a gauntlet that was taken up willingly by Kitchener's volunteers.

Military dynasties

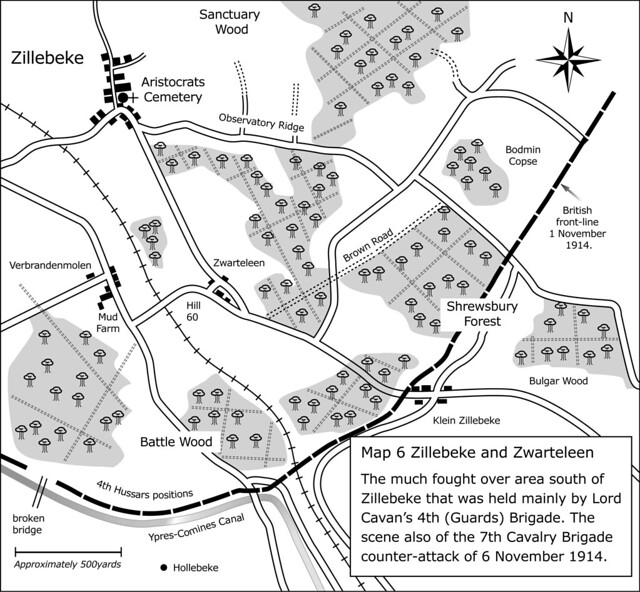

The men recorded in the Zillebeke cemetery register took part in all the decisive engagements of October and November 1914: Langemark, Gheluvelt, Hollebeke, Zandvoorde, Messines and the battle for the woods around Zillebeke. They served principally with Douglas Haig's I Corps and Edmund Allenby's Cavalry Corps. Fourteen are either from, or attached to The Foot Guards and Household Cavalry regiments, one is a 13th Hussar and one is a senior officer from an established county infantry regiment. Two private soldiers and an NCO from 1914 rest with their more distinguished counterparts, serving as a sharp reminder that death in battle does not discriminate.

Without exception all of the British officers commemorated at Zillebeke attended public schools before being commissioned and of these, eight passed through Sandhurst. Zillebeke is also more of an ‘aristocrats' cemetery' than appears at first glance, eight officers and their families are listed in Burke's Peerage, one is a Russian aristocratic and three have entries in Burke's Landed Gentry. The remainder either have links to the aristocracy through marriage or are sons of wealthy professional families. Of the three rank and file soldiers, two are regular soldiers each with at least eighteen months service and one is a territorial volunteer.

These men were part of a regular army that had evolved from nearly a century of reform and reorganization. Aristocrats Go to War uses the career experiences of the Zillebeke men to trace the historical and political processes that saw the British Army emerge from being the plaything of the aristocracy to the professional organisation it became in the early twentieth century. Unquestionably by 1914 the regimental system that fostered regimental pride and spirit was at the very heart of British military tradition and a good proportion of officers were bound to their regiments by strong family ties and were part of a close knit community. Many, like Lord Bernard Gordon Lennox, a son of the Duke of Richmond, had married the sister of another officer in the regiment and followed his father and grandfather into the regimental fold. His brother, Charles Gordon Lennox, married a daughter of Thomas Brassey the railway pioneer and the eldest of the Brassey brothers, Henry Brassey, was his brother-in-law. These military dynasties were commonplace as family names became linked to regiments to the extent that, even in 1914, connections rather than ability still continued to cloud judgement to some degree when it came to promotion.

Despite the Haldane reforms, the officer corps that went to war in 1914 was still very much educationally and socially exclusive. However, the previous dominance by the aristocracy and landed gentry was in decline, in fact by 1912, apart from the Household Division and the Foot Guards regiments, the aristocracy and landed gentry comprised only 41 per cent of the entire officer corps and some 64 per cent of the officers holding the rank of Major General and above. But the old values were still very much to the fore. There is no doubt the officer corps was still influenced very much by the values of the gentry and officers were expected to behave within the largely unwritten code of gentlemanly behaviour. When on active service it went without saying that regimental officers were expected to display leadership and gallantry, first out of a trench when on the offensive and last out in retirement.

‘Poor things'

Aristocrats Go to War is essentially about First Ypres and the circumstances leading to the deaths in action of each of the Zillebeke men. Of the numerous actions in which they took part it was that over the two days of 6 and 7 November 1914 which was one of the most costly. Up until 6 November the 2nd Battalion Grenadiers Guards (2/Grenadiers) positions in the woods at Zwarteleen had been systematically shelled on a daily basis in an attempt to break the line and force a gap through which the waiting German infantry could advance. Up to that time German infantry attacks had repeatedly failed to make an impression against the resolute rifle and machine-gun fire that the British front line troops poured into the advancing waves of infantry. Lieutenant Colonel Wilfred Smith, commanding 2/Grenadiers, noted in a letter to his wife that ‘we have killed hundreds in the last few days and these woods are full of them, poor things.' But far from giving up, the German infantry were now seen to be entrenching a new line only some 300 yards away, clearly another infantry assault was being planned.

The attack came after the early morning mist had cleared. The French infantry were holding the defensive line that ran roughly from the Ypres-Comines canal to the Klein Zillebeke road. North of the French were the Irish Guards and beyond them 2/Grenadiers in position along the line of the Brown Road. With the clearing of the mist came the expected artillery bombardment which was followed two hours later by German infantry attacking all along the line. The initial wave was repulsed everywhere leaving heaps of enemy dead and wounded in the now bright sunshine of the morning. The second assault, a far more determined affair which appeared to be focused on the French positions, succeeded in breaking their resolve and opening up a considerable gap. The French retirement in the face of this attack was the beginning of a collapse that impacted directly on the now exposed right flank of the Irish Guards and it wasn't long before the Irish line gave way completely, leaving the Grenadiers trench line open to a similar flanking attack. The whole house of cards was now in great danger of coming down and it was only the fortitude of the Grenadiers who stood their ground and managed to swing their threatened flank back to the relative security of the Brown Road which averted a total disaster.

As soon as news filtered through that the Irish Guards' line had broken, Colonel Smith sent Lieutenant Harry Parnell (Lord Congleton) and Number 3 Platoon with Lieutenant Carleton Tufnell and his machine-gun section to open fire on the German infantry which were advancing through the gap. Whilst this did not hold them up, it did slow the advance as the Grenadiers fired down the wide rides in the wood directly into the German right flank, exacting a heavy toll on the German infantrymen. The situation was far from being contained, however. Once in position it would have been immediately clear to Tufnell that, despite the fire-power of his machine guns and the additional support of Harry Parnell's rifle platoon, more support was going to be needed if the breakthrough was to be halted. Fortunately help was at hand; an urgent call had been sent to Brigadier General Kavanagh's 7th Cavalry Brigade at Sanctuary Wood for assistance. This order set in motion a dismounted cavalry action that many feel was more brilliant than, and just as crucial as, that of the 2nd Worcesters a week earlier at Gheluvelt. In fact if the German breakthrough had succeeded at Zwarteleen there were precious few, if any, reserves left to have prevented Ypres from falling.

Spirited bayonet charge

Kavanagh's troops were directed to approach over Observatory Ridge to avoid revealing themselves too much before they deployed across the line of the French retreat. Just short of the village of Zwarteleen the brigade dismounted under fire and with the Royal Horse Guards held in support, the two regiments of Life Guards advanced at the double astride the Zillebeke-Zwarteleen road towards the Klein Zillebeke ridge to meet the enemy. With them went Harry Parnell and Carleton Tufnell together with some Irish Guards and those French troops that could be found. The 1st Life Guards (1/Life Guards) with Lieutenant Hon Reginald Wyndham and Second Lieutenant Howard St George attacked the trenches that had been abandoned earlier in the morning by the Irish Guards, their spirited bayonet charge was enough to expel the occupying German troops and regain the lost position. Realising just how weak the line was at this point, Harry Parnell collected together several Irish Guardsmen to strengthen his own platoon in the hope of linking up with the Royal Sussex on his left. The Irish Guardsmen were completely devoid of weapons and ammunition, having abandoned everything when they had left their trenches in near panic; but Harry went out personally and collected rifles and ammunition from casualties to re-arm the Irishmen. Placing them amongst his own men, he was able to hold the gap all through the hours of darkness until relieved the next morning. Tragically he was killed four days later.

While this was taking place the 2nd Life Guards (2/Life Guards) with Second Lieutenant William Petersen advanced along a line that ran from the edge of the railway line across the open ground to the village of Zwarteleen. The 2/Life Guards war diary is almost certainly the most accurate account of the subsequent fight:

‘ The regiment ... was ordered to establish itself on the Klein Zillebeke ridge keeping in touch with the 1st Life Guards on the right, who were to conform with the right of the Guards Brigade. Major Hon Dawnay [commanding] ordered B Squadron across the open [to] occupy the high ground in front. D Squadron was sent across the Zillebeke-Zwarteleen road to secure the right flank by moving parallel to the railway. C Troop and machine guns were kept in reserve ready to support B Squadron. The latter squadron succeeded in reaching the edge of the wood on the ridge after some fighting owing to the enemy being in possession of several houses. Almost at once the right flank of B Squadron became open to enfilade fire which caused Major Dawnay to order the squadron to fall back slowly by troops. ... The squadron was then ordered to fix bayonets and charge the wood while C Troop was taken by the CO to fill the gap which had occurred between the two squadrons. This troop vigorously attacked the village of Zwarteleen using the bayonet with great effect, taking a certain number of prisoners. B Squadron meanwhile drove back the enemy several hundred yards and occupied a ditch 200 yards from their position.'

The village was filled with British, French and German troops fighting at close quarters; the aggressive energy of the cavalrymen had stirred their allies and French and British fought alongside each other to push the enemy back along the road. They were successful; the gap was closed and Zwarteleen recovered. But the fight was far from over. Just when it appeared the situation had been restored to some resemblance of normality, the French on the right of 2/Life Guards gave way again, opening up yet another gap which the enemy was quick to capitalise on. With the daylight beginning to fade, the exhausted cavalrymen turned once more to meet the German advance head on and for a moment or two the outcome hung in the balance. Incredibly they managed to stand firm and despite having to abandon some of the hard-won ground gained earlier in the afternoon by Dawnay's men, the line was once again securely in British hands. At 9.30 pm that evening the cavalry began to be relieved by 3 Brigade which had marched from Bellewaarde Farm and 22 Brigade which had been brought up from reserve at Dikebush in motor buses.

What a cost!

The extent of the cavalry's casualties was not immediately apparent to the men of 7 Cavalry Brigade as they returned to their billets at Mud Farm that night. Only when the roll calls were completed the next day would the full human cost of the previous afternoon's action become evident. And what a cost! There is no doubt that this bold and inspiring charge by the cavalry had saved the day and prevented the 4 Guard's Brigade from being annihilated, but the casualties had been heavy. From a brigade which on 5 November had been unable to muster more than 600 men in total, casualties amounted to six officers killed and a further eleven wounded with 67 other ranks killed, wounded or posted as missing. Amongst the 1/Life Guards casualties was Regy Wyndham, three of his men had been wounded and he had been killed leading his beloved troop into action. Many in the regiment considered Regy's death the saddest loss of the day:

‘So well liked was Sinbad [Regy Wyndham's nickname] amongst the troops that when darkness fell that same night, two drivers from the machine gun section, Rubber Reeves and Tinker Underwood, got two horses and a half-limber, galloped up to the scene of the counter-attack, and brought back his body for burial in a near-by churchyard. They received no official recognition for this action but Sinbad's brother, Lord Leconfield, sent them both a token of his gratitude and a letter of thanks.'

A lack of firm information

2/Life Guards had borne the brunt of the day's action and it was during the advance through Zwarteleen that William Petersen fell. We will probably never know exactly where he was hit, but as most of the regiment's casualties occurred during the final British counter-attack of the day by B Squadron and C Troop, it is highly likely he was shot by German infantry firing from the shelter of outlying houses on the eastern edge of the village. Accounts of the action tell us that he was killed leading his troop as they advanced under heavy fire and that shortly before his death he and his men were ‘keeping back a very strong attack of the enemy.'

Precisely when and where Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Wilson, the commanding officer of the Royal Horse Guards (Blues), was killed is also difficult to pinpoint as there are conflicting accounts of his death.

The official history of the Household Cavalry, written by Sir George Arthur, describes Gordon Wilson with a rifle and bayonet in hand leading his men into the woods with a ‘cheery laugh bubbling up'. Moments later a bullet ‘pierced his brain, and without word or a moan he sank to the ground'. This account is very different to that of the Blues' war diary:

‘We drove the enemy back through the wood, the edge of which was held after by the 3rd Cavalry Division. Captain Lord Gerard was wounded but otherwise we had few casualties in the advance. When it got dusk we were ordered to withdraw to the trenches about 80 yards in the rear. In doing this we came under fire from some of the enemy who were in advance of their line and Colonel Wilson and Lt. A. de Gunzburg were killed and Captain E P Brassey and Captain Lord Northampton were wounded.'

An account written by General Kavanagh in a letter to Gordon Wilson's wife, Lady Sarah (image below), on 8 November 1914 suggests he was killed during the advance the Blues made in support of C Troop towards the end of the afternoon, rather than later in the evening when the Blues were withdrawing after being relieved:

‘The Brigade had successfully carried out the main part of its task and regained a lot of ground, when I ordered it to halt, and urged the French commander to reorganise his troops and reoccupy the trenches they had left. This he said he would do, and sent about 400 of them forward. They had, however, only advanced about 100 yards when they seem to have been seized by a panic, and came hurrying back saying the Germans were making a counter-attack. I called one squadron of the Blues and one of the 2nd Life Guards to meet this attack, but they were practically swept away by the retreating French and it was at this moment that most of the casualties occurred and that your husband was shot. He was shot through the head, and his death must have been instantaneous.'

Of the three accounts I am more inclined to accept the version in the Blues' war diary. Kavanagh was correct in describing where on the battlefield Gordon Wilson was killed but his timing was out. Arthur's account which was published in 1926, I suspect has been the subject of an overenthusiastic pen and at the very least must be considered to be inaccurate.

There is a similar lack of firm information regarding the death of Second Lieutenant Alexis de Gunzburg. Contemporary accounts describe him being shot down while running across an open field under fire. The war diary describes his death taking place at the same time as Gordon Wilson, which would be in keeping with the view that de Gunzburg, as official interpreter, would be close at hand should his commanding officer require his services. Other sources have de Gunzburg acting as a runner and relaying Gordon Wilson's orders which would be consistent with him being killed crossing an open field. However, I tend to lean in favour of the war diary; Alexis de Gunzburg was probably killed close to his commanding officer whilst the Blues were being relieved from their positions.

Captain Norman Neill's death, which occurred less than a week after he had returned to duty, was another great loss to the Brigade. ‘His death, I think' wrote Kavanagh, ‘must have been instantaneous and without pain, as I saw him two minutes after he was hit'. Neill was Kavanagh's Brigade Major and had been sent by his commander to order the Blues into action in support of 2/Life Guards after the French had given way on the second occasion. He was hit while returning to brigade headquarters.

Fighting for survival

So what of 2/Grenadiers who were fighting for their survival along the Brown Road? Once through the gap created by the French retreat, the advancing German infantry quickly enfiladed Number 1 Company which accounted for most of the 75 NCOs and men who were killed and wounded. The timely arrival of 7 Brigade and the subsequent counter attack took the pressure off the battalion but at some point during the counter attack Carleton Tufnell was shot through the throat and died of his wounds soon afterwards. Writing on 8 November, Captain Eben Pike, the battalion's Adjutant, mourned his passing:

‘Poor young Tufnell was killed the day before yesterday. He is the second machine gun officer we have had killed and was engaged to a girl in England. Poor chap, he was always so excited about the post coming and getting his letters.'

The Grenadier Guards war diary described the events of 6 November as a ‘trying and critical day'; a view shared by 19-year-old Second Lieutenant John Lee Steere, in what was his second day of front line action, agreeing ‘we had it hard yesterday'. Tragically Lee Steere had only eleven days left to live.

Dawn on 7 November was another misty and dull start to the day. Late the previous evening the 1st Battalion the Gloucester Regiment (1/Gloucesters) had arrived as part of the 3 Brigade reinforcements that had been drafted in to bolster the Zwarteleen frontage. Like 3 Brigade, 22 Brigade was desperately under strength. Of the 4,000 officers and men that had marched into battle in October 1914 only three officers and a few hundred men remained. As for the Gloucesters, despite being reinforced a few days previously by a further 200 men, the 1/Life Guards war diary noted they were still unable to muster enough rifles to effectively occupy all of the front line allocated to them. It was only at 2.30 am on 7 November that 1/Life Guards were finally able to leave the positions they had fought so hard to regain the previous day. Commanding A Company of the Gloucesters was Captain Robert Rising who as a seasoned veteran would have felt apprehensive at the thought of his exhausted troops having to mount a counterattack the next morning against infantry who were relatively fresh and in strongly held positions. At 6.00 am on 7 November orders were received by the Gloucesters from Lord Cavan to assist in the 22 Brigade attack on Zwarteleen. Lieutenant Grazebrook's account described Robert Rising's last battle:

‘The battalion pushed forward in two lines, Captain Rising leading the first and Major Ingram the second about 50 yards behind. On issuing out of the village of Zwarteleen the battalion was met by an intense rifle and machine gun fire and it was found the enemy were holding some of the outermost houses of the village ... Officers and men were much too exhausted to do more than clear a few of the houses. Most of the men had to lie down in the open all day and only a few could get back to the trenches they had dug the night before. Major Ingram and Lieutenant Halford tried to check the tendency to retire to the cover of the houses but there were not enough officers left to lead the men forward. Lieutenant Kershaw with his platoon of A Company on the right had been cut off and nothing more was ever heard of him. Major Ingram was wounded in the knee whilst crossing the road under full view for the fifth time when attempting to point out the line to be held. He was able however to reach Captain Rising and discuss with him the situation before being taken back to the dressing station. Captain Rising himself was carried back to the dressing station a few minutes later, mortally wounded.'

While this attack was being carried out German artillery kept up their daily bombardment of the British and French positions; the 2/Grenadiers, who were now dug in along a fresh line parallel to the Brown Road, reporting they had been shelled for most of the day. Casualties in the battalion for 7 November were nineteen killed, forty-six wounded and three missing. One of the dead was the 20-year-old Londoner, Private Walter Siewertsen, who on the day of his death had completed one year and 214 days in the service of the Crown. He was buried soon after at Zillebeke churchyard with Robert Rising who had died of his wounds at the battalion dressing station. There they joined the casualties of the previous day which included Carleton Tufnell, Gordon Wilson, Regy Wyndham, William Petersen and Alexis de Gunzburg in a diminutive plot on the Western Front in Belgium which is as thought provoking as it is unique.

The register of 1914 burials in Zillebeke churchyard cemetery

| Grave |

Rank |

Name |

|

Regiment |

|

A.1. |

L/Corporal |

Whitfield |

James William |

2nd Coldstream Guards |

|

A.2. |

2nd/Lieutenant |

St George |

Howard Avenel Bligh |

1st Life Guards |

|

A.3. |

Private |

Gibson |

William |

1/14 London Scottish |

|

A.4. |

Captain |

Neill |

Norman |

13th Hussars |

|

B.2. |

Lt/Colonel |

Wilson |

Gordon Chesney |

Royal Horse Guards |

|

C.3. |

2nd/Lieutenant |

Petersen |

William Sinclair |

2nd Life Guards |

|

D.1. |

Lieutenant |

Tufnell |

Carleton Wyndham |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

E.1. |

Lieutenant |

Stocks |

Michael George |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

E.2 |

Lieutenant |

Parnell (Congleton) |

Henry Bligh Fortescue |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

E.3. |

Major |

Gordon Lennox |

Bernard Charles |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

E.4. |

Private |

Siewertsen |

Walter Frederick |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

E.5. |

Major |

Rising |

Robert Edward |

1st Gloucesters |

|

E.6. |

Captain |

Dawson |

Richard Long |

3rd Coldstream Guards |

|

F.1. |

Lieutenant |

Lee-Steere |

John Henry Gordon |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

F.2. |

Captain |

Symes-Thompson |

Cholmeley |

2nd Grenadier Guards |

|

SM1 |

Lieutenant |

Wyndham |

William Reginald |

1st Life Guards |

|

B.1. |

2nd/Lieutenant |

De Gunzburg |

Alexis George |

11th Hussars |

Article and images contributed by Jerry Murland