The British Invasion or 'The Western Front without the Trenches'

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The British Invasion or 'The Western Front without the Trenches'

[This article first appeared in Bulletin No. 117 Pages 21-24. Western Front Association members received both this magazine and Stand To! three times a year as part of their membership package.]

The now shuttered ‘Sandy’s Cycle Shop and Books’ was tucked into an out-of-the-way corner of the Leaside Business Park. But visibility, or rather invisibility, wasn’t its only problem. Small, independent retailers of any sort, even such quirky amalgams as Sandy’s, are rapidly disappearing from Toronto’s streetscape, as they are across many increasingly unaffordable metropolitan centres.

Disappointed as I was to lose Sandy - to a commuter bicyclist such as myself a conveniently located bike repair shop is worth its weight in gold - it did encourage a final trawl of his shelves, as did a going-out-of-business fifty percent off sale. A first edition of a Western Front memoir I’d not yet read, Sidney Rogerson, Twelve Days, in excellent condition, appeared before me. A foreword by Liddell Hart and accompanying plates produced during the war by Stanley Cursiter, at the time of publication Director of the Scottish National Gallery, including a single in full colour, sealed the deal.(1) It came home with me.

Twelve Days captures the travails and mood of Rogerson’s 2nd West Yorkshires, a regular battalion, opposite Le Transloy as the Somme battles wound down in November 1916, I soon discovered. The approaching hardship of another winter campaign, the mud (could it be otherwise), the personalities, the seemingly randomness of casualties caused by shelling, including those from friendly fire, are pretty standard fare for the Western Front memoir genre; Twelve Days is no exception. Yet there is no attack, no bloody raid, no tragic death of a mate (although an officer’s mysterious disappearance in No Man’s Land prompts plenty of lurid speculation) - nothing, in fact, on which to peg the narrative. This was Rogerson’s point, Liddell Hart explains: it’s the ‘normal atmosphere’ of a battalion at war on the Western Front.(2)

As an antidote to the disillusionment school of memoir writing prevailing in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Rogerson was determined to reveal the trenches not as places of horror and futility but as ones in which their occupants endured, adapted and occasionally shone - despite everything.(3) And he surely succeeds. But I was disappointed: it deals only with the trenches, and it ends when the Yorkshires are relieved. We know nothing about what transpired during the ensuing thirty days at rest in Oisemont, well behind the front. But that criticism, to be fair to Rogerson, is a personal, academic, one.(4) At the same time, and more troublingly to my mind, it speaks more broadly to the current understanding of the Western Front.

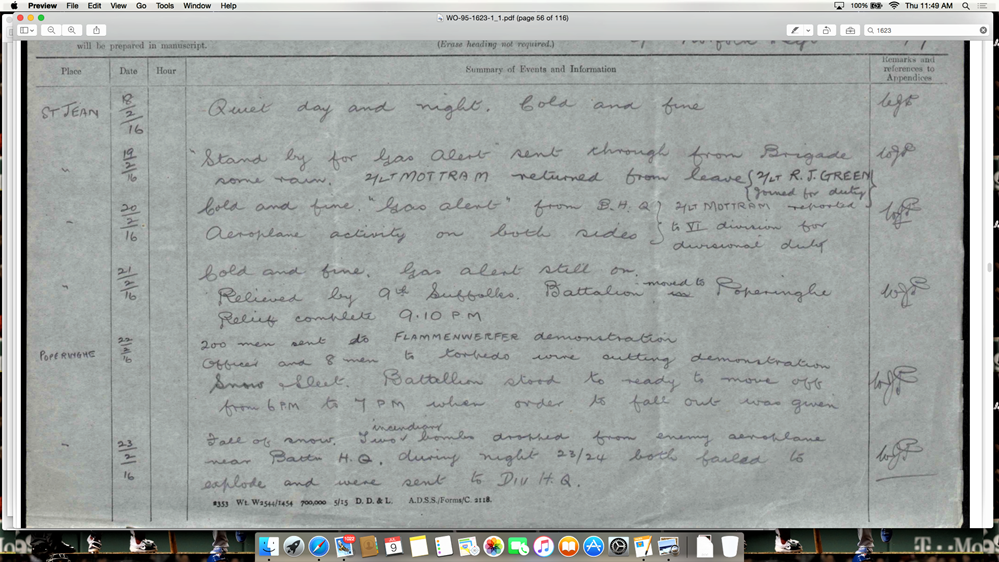

Adopting a trench-centric approach (trenchism, if you will) is nothing especially new. When I began postgraduate research in the autumn of 1993, it became very clear, very quickly, that the authors of the published memoirs, novels from experience, and other assorted military records I was consulting (the First World War unit war diary class at The National Archives (TNA), War Office (WO) 95, is notorious (5)) skirted around the time they spent out of the lines, which, under the circumstances of the middle trench war years and depending on how one defined ‘out of the lines’, hovered (for argument’s sake) around fifty per cent.(6)

And just to be clear: I don’t believe writers were purposely obfuscating their service on the Western Front, emphasizing time in the trenches at the expense of time behind the front. On the contrary, they were merely trying to focus on what they deemed most militarily significant, what was likely most memorable, and, not insignificantly, most interesting to readers. In the case of commercial publications, the urgings of editors and publishers cannot be discounted, if difficult to gauge with any precision. Except anecdotally, few veterans, either at the time or in the postwar era, wrote about behind the front. At both a popular and scholarly level, we live with the consequences of this weighting to this day.

However, neither a serendipitous reading of a First World War memoir nor an against-my-better-judgment viewing of the excruciating Sam Mendes 1917 entirely account for me mentally reviving the historiography of the Western Front.

No, the death of Hugh Peniston Cecil on 11 March had much more to do with it.

Amongst my first introductions as a fledgling postgraduate at Leeds University, Cecil was nothing less than a godsend. Besides an exceedingly generous offer of research lodging in West Hampstead, he also conducted a preliminary sweep of records at the then Public Records Office, now the TNA. Most importantly at our first meeting he rummaged through shelves of books that stretched to the ceiling and book towers that did likewise in his School of History office until, somehow, conjurer-like, he produced a copy of Ralph Hale Mottram, Spanish Farm Trilogy (1927).(7)

Small wonder that Cecil instinctively knew how important Mottram (1883-1971) would be to my study of troops and civilians behind the front, if it was to proceed at all, much less succeed, for much of what we know about Mottram’s life, beyond his own later writings, is owed in fact to a chapter in Cecil’s Flower of Battle (1995), entitled ‘Disenchanted Observer’.(8) Of course - Mottram.(9)

Working at the same Barclay’s branch in Norwich where his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had before him, Mottram enlisted in September 1914.(10) Older and with more life experience than the typical Kitchener man, including two volumes of poetry published under a pseudonym, he was given stripes (Vera Brittain’s Roland Leighton was his platoon commander at Peterborough in early 1915), and a commission soon followed.

Mottram was deployed to Ypres as a reinforcement subaltern with the 9th Norfolks in October 1915.(11) While he was fortunate to escape that novice battalion’s bloodletting at Loos, Mottram was soon overwhelmed by stress and exhaustion and the foul weather, and was evacuated via Essex Farm dressing station.(12) A convalescence in sunny Nice was just what the doctor ordered. Literally.

Mottram’s return to the front in January 1916 was short-lived. The war’s character, he noticed, was changing. Beginning after Loos but accelerating during the Somme, the war machine was growing, becoming more impersonal and more specialized, with less scope for individual initiative. Within weeks he proceeded to 6th Division headquarters, where, answering a call for officers with knowledge of French, he took up the newly-created post of Divisional Claims Officer.(13) Adjusting claims for losses of and damage to civilian property and arranging for the rent of land and buildings, Mottram travelled widely behind the battle zone, especially in the areas of First and Second Armies. He held lengthy postings in Boulogne, Doullens and Hazebrouck.(14)

It was, in many ways, a remarkable turn of events. While never completely out of danger, Mottram never served in the trenches again, much less went over the top (though in the harried days of the April 1918 German Flanders offensive he was never far from the fighting, with Hazebrouck evacuated but never occupied). Well aware of his good fortune, to which he attributed his mother’s insistence on his attending a French boarding school and several French holidays and which held even following his Christmastime marriage in 1917, usually thought to be a (superstitious) soldier’s death sentence, Mottram survived the war relatively unscathed. He could not, he well knew, say the same about the men with whom he had originally enlisted and served in the Norfolks.

When he began to write about the war in the 1920s, Mottram could have, as did so many others, defaulted to his trench service. It was after all the thing to do, the thing publishers and editors expected, the thing the public, all acknowledged, increasingly craved. He did not, thank goodness (though it initially made getting published more challenging). Instead he turned his lengthy and varied experiences behind the front into The Spanish Farm (1924), Sixty-Four! Ninety-Four! (1925), and The Crime at Vanderlynden’s (1926), all of which were published collectively in 1927 as the Spanish Farm Trilogy. None of these works is strictly autobiographical, writes Cecil, nor are they entirely fictional. Nor, in fact, is there much ‘about the fighting in it, for what really interested Mottram was the whole world of the Western Front and how it functioned, rather than the moments of extreme danger.’ (15)

It was all so unprecedented, that enormous military machine. Hundreds of thousands of troops from every corner of the isles and empire flooded into northern France and Flanders. Barely keeping their heads above water, civilians ran estaminets and shops behind the front and continued to farm as best they could, sometimes up to the trenches, provided billets and fields for baseball and football and camps and hospitals and aerodromes and manoeuvres and horse lines and parades and vin rouge and occasionally intimacy, and were crucial reminders of the civilian life for which many Kitchener men felt they were fighting and to which they longed to return. But in the meantime, there were maires and burgomasters to be bargained with, subalterns to be reprimanded, peasants to be cajoled, and omniscient French liaison officers to be appeased. Into this panoply of personality and pandemonium Mottram was cast, and out of it, like an intricate tapestry woven from the coarsest wool, emerged his Spanish Farm Trilogy.(16)

An online search reveals that Mottram’s wartime books - books that sold well in the interwar years (the Spanish Farm won the 1924 Hawthornden Prize), made Mottram a sought after speaker and commentator, and launched his literary career, over sixty books published - are no longer in print. Except through second-hand books and library editions, how will, I wonder, new generations come to learn of the indomitable Madeleine Vanderlynden? The Sisyphean-like Lt Dormer? The unconquerable Spanish Farm?(17) What’s worse, other than a blog post and newspaper piece focusing on his literary legacy, was his near total absence during the centenary - baffling, to my mind, if not entirely unexpected.(18) Until a full-length biography appears - his papers, all 149 boxes’ worth, are held at the Norfolk Record Office - I suspect this will remain the case.(19) But even this, confronted by trenchism, may not be enough.

Having disappeared into that post-doctorate purgatory of non-tenured, under-employed academia two decades ago, I had lost track of Cecil, at least, that is, until recent years, when, well overdue, given his importance to my early research, I posted a letter along with a copy of my own monograph.

I never found out just what Cecil thought of the book, which took its cues from issues he himself had raised in his Mottram chapter. If he did get around to reading it, he would have noticed that we ended up sharing a passion for Mottram’s forgotten wartime oeuvre and his neglected insight into the Western Front. On Mottram Cecil concludes: ‘No English author explored with more honesty and plain intelligence the tragedy of the Great War.’ (20)

I couldn’t agree more.

REFERENCES

- Sidney Rogerson, Twelve Days, fwd. B. H. Liddell Hart (Arthur Barker Ltd., n.d. but 1933).

- Ibid, p. vii. Italics in original.

- Rogerson calls out both Remarque and R. C. Sherriff. See ibid, p. 143

- My own interests are in billeting, camp and staging areas - that liminal area between the military world of the trenches and the civilian world in the rear where both British troops and local civilians coexisted. See Craig Gibson, Behind the Front: British Soldiers and French Civilians, 1914-1918 (CUP, 2014).

- See https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/centenar y-unit-war-diaries/

- This is a tricky question, with no single,straightforward answer, and one that requires a study in its own right. Certainly the most advanced trenches were at ‘the front’, with mortars, snipers, raids, and barbed wire ever present reminders of the enemy’s proximity. But when units were rotated to support trenches and strongpoints to the rear, were they? And reserve positions a further back? Between fronts, too, material circumstances could vary widely, as they did in the passage of time. Even ‘at rest’ is somewhat of a misnomer because any unit, anywhere in Flanders, at any time, could be called upon in an emergency. I discuss these issues in Behind the Front, pp. 11-26, 109-46, passim

- Ralph Hale Mottram, Spanish Farm Trilogy, 1914-1918 (Chatto & Windus, 1927).

- Hugh Cecil, The Flower of Battle: How Britain Wrote the Great War (South Royalton, VT, USA, 1996), pp. 107- 34; originally published as The Flower of Battle: Britain Fiction Writers of the First World War (Martin Secker & Warburg, 1995). The main title is taken from a Mottram poem.

- Mottram’s own wartime account can be found in R. H. Mottram, John Easton, Eric Partridge, Three Men’s War: The Personal Records of Active Service (New York and London, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1930). Mottram’s account is entitled ‘A Personal Record’, and later, republished, comprises much of R. H. Mottram, Through the Menin Gate (Chatto & Windus, 1932), which includes a dozen other, shorter, previously published essays and stories. See also Mottram, Ten Years Ago: Armistice & Other Memories; Forming a Pendant to ‘The Spanish Farm Trilogy’, fwd. W. E. Bates (Chatto and Windus, 1928).

- On Mottram’s prewar life in Norwich, see R. H. Mottram, The Window Seat: Or Life Observed (Hutchinson, 1954), which also includes brief wartime chapters.

- Mottram’s joined the battalion on 12 October 1915. See TNA WO 95/1623.

- 15 November 1915, ibid.

- ‘2/LT MOTTRAM reported to VI division for divisional duty.’ 20 February 1916, ibid. His personal papers mention that he appeared in Divisional Orders as Divisional Claims Officer on 3 March 1916. Letter 3 March 1916, Box 134, The Papers of R. H. Mottram, Norfolk Record Office. See also his service file: TNA WO 339/40148.

- In sum, Mottram’s ‘trench’ service on the Western Front amounted to about nine weeks. He served with the Norfolks from 12 October to 15 November 1915, when he went sick, returned on 8 January 1916, and was posted to division on 20 February. Besides the usual rotation amongst front, support, reserve and at rest positions, he was on leave 8-19 February 1916. If not significant in quantity, however, his time at the front was eventful and often in trying conditions, to which both the unit war diary and his own writings attest. See ibid and ‘A Personal Record’.

- Cecil, Flower, pp. 107-8.

- Written on the eve of another war, R. H. Mottram, Journey to the Western Front: Twenty Years After (G. Bell & Sons, 1936), builds on the themes highlighted in the Spanish Farm Trilogy and ‘A Personal Record’.

- Thankfully there do appear to be inexpensive imprints and digital editions now available

- See Mark Connelly’s blog ‘The Spanish Farm Trilogy’, https://blogs. kent.ac.uk/gateways/2014/11/07/ spanish-farm-trilogy/ [accessed 4 July 2020]; and Patrick Reardon’s ‘The underappreciation [sic] of R. H. Mottram’s World War I novels’, in the 10 December 2015 Chicago Tribune, https://www.chicagotribune. com/entertainment/books/ct-prj-rh- mottram-trilogy-20151210-stor y.html [accessed 4 July 2020].

- See the Papers of R. H. Mottram, Norfolk Record Office, Norwich.

- Cecil, Flower, p. 134.

Article by Craig Gibson