The British Route to War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The British Route to War

Britain's entry into the Great War is far more complex than the reason for the country embarking on the Second World War.

The following factors were mentioned by Sir Edward Grey (Foreign Secretary) in Parliament on the eve of war:[1]

- "Present Balkan Crisis" (ie assassination)

- Moroccan crisis

- Friendship with France

- Possible risk to (French) coast

- Trade routes through Mediterranean

- Belgian neutrality

- Dutch / Danish independence

- British Prestige / Trade

- European Trade

- European Alliance

To the above could be added the following unmentioned issues:

- Balance of Power

- Arms Race

- Anti-Germanism

- German Foreign Policy

- Colonial Expansion

- The Balkans

- Russian Expansionism

Many of the above are interlinked, but I hope to show how these factors played their parts, to greater or lesser extents, in Britain's decision to go to war.

Introduction

Until the mid-19th century, Britain's natural ally in Europe had been Germany and our natural enemy had been France. What caused the shift of alignment away from Germany and towards France?

By the late 19th century, Britain dominated the world like no country before. Trade was at the centre of this domination and, whilst trade with Europe was important, it was the trade with the British Empire that was the main source of Britain's wealth. Unsurprisingly, British shipping was an indispensable factor in this domination and therefore protection of the shipping and trade routes was at the forefront of politicians' minds.

There were, of course, several nations who would have liked to have challenged Britain's position. These were the USA, Russia, Germany and France. Whilst the USA was no doubt becoming powerful and Russia was seen to have become enfeebled following the Japanese victory in 1904, it was the change in balance of power between Germany and France that was at the heart of the problem.

The threat to Britain's trade and the change in focus away from France as the main challenger to Britain's position can be put down to German unification under Bismarck and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

Treaties

France's defeat by Germany in the Franco-Prussian War had left France with little chance of restoring herself to the position of being the dominant power in Europe. France had already realised her position was under threat and had tried to stop German unification. The only way now of regaining a strong voice was via an alliance.

Bismarck realised that France would seek alliances in order to be in a position to challenge Germany for the return of Alsace and Lorraine; he worked to ensure Germany entered into treaties that would foil France's attempts at creating alliances. The main German treaty was with Russia and a further treaty with Austro-Hungary created, in 1873, the League of the Three Emperors. The renewal of this alliance in 1881 ominously gave Austria the right to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina. Additional to this treaty, both Italy and Britain leaned towards Germany.

Britain was keen to avoid Russia gaining control of the Dardanelles Straits; this could only result in them remaining Turkish. Following the Russo-Turkish war of 1877 and the peace treaty of the following year, Britain sided with Turkey. This strained relations between Russia and Germany but meant that Germany was closer to Britain.

Because of Austrian economic penetration of the Balkans, Russia did not renew the treaty in 1887. Bismarck, worried about a link up between France and Russia, ensured a 'Reinsurance' treaty was signed between Russia and Germany; although weaker than the earlier treaty, it was designed to ensure each country's neutrality in the case of the co-signatory entering into a war with another great power.

Italy, which had been in diplomatic conflict with France, had meanwhile, in 1882, joined the German / Austrian / Russian alliance. This bloc (Germany / Austria / Russia / Italy), although useful for Germany's purposes of preventing France making alliances, did have its own tensions, principally between Austria and Russia over the Balkans, but also between Italy and Austria.

The Bismarck-built edifice of alliances was about to crumble. Kaiser Wilhelm I died of cancer shortly after coming to power and the young Kaiser Wilhelm II came to the throne with what could be described as a personality disorder, possibly due to a withered right arm.

Wilhelm II forced the resignation of Bismarck in 1890. It can be no coincidence that following Bismarck's resignation, Germany did not renew the Reinsurance treaty with Russia. This alarmed the Russians, resulting in the French and Russians becoming diplomatically closer over the following years. (McCullough [2] mentions a 1910 conference between Russia and France, which agreed that mobilisation of the German Army would oblige Russia and France to mobilise immediately and simultaneously. This indicates the intention of creating a defensive alliance, as there was no apparent thought given to Russia or France mobilising first.)

Bismarck's work was damaged by France entering into a trade agreement with Italy in 1898. The new King of Italy further undermined the German / Italian accord. Victor Emmanuel III "...detested Austria, disliked the Kaiser and wanted out of the alliance". [3] This resulted, in 1900, in Italy and France coming to an agreement over their North African colonies. Although still part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria, Italy had strengthened her links with both France and Russia.

Whilst Germany was seemingly intent on closer relations with Britain and supported British policy in Egypt, relations became strained over the creation of a German colony in South West Africa in 1883. (This seems to be one of the few examples of a deliberate German foreign policy of colonisation.) Whilst relations improved, the fiasco of the Jameson raid led to the Kaiser sending a telegram to Paul Kruger, the leader of the Boer republic in the Transvaal, congratulating him on defeating the Jameson raid; this created an uproar in Britain's press. Anti-Germanism took other forms such as the publication of an Alan Burgoyne novel "The War Inevitable" in 1908. The British press was also whipped up after Lloyd George's Mansion House speech in 1911. Other perceived anti-German issues included the Conservative call for Tariff Reform (ie taxing imported goods which would hurt Germany).

Following soon after this incident came the Boer War, when Britain's prestige was lowered throughout the world. Many countries took advantage at this time in supporting the Boers; not least in this was Germany.

Germany's perceived anti-British attitude during this period resulted in Russia replacing Germany as Britain's most favoured ally – at least in the eyes of the British press. McCullough suggests that this shift was, at political level, due to the belief Britain had to either ally with Germany against Russia or come to an accommodation with Russia and France. He suggests that underestimating Germany, as either a friend or enemy, was a mistake – the politicians should have been more aware of Germany's value as an ally or danger as an enemy.

Britain's entry into the field of alliances started with the Anglo – Japanese treaty of 1902; this was initiated in order to prevent Russian expansion in the Far East. Japan's defeat of Russia in October 1904 checked Russia's Far Eastern ambitions and made a British alliance with Russia far more likely, with a by-product of this being the security of India – Russia had been threatening expansion through Afghanistan into India for some time. [4] Conversely, the defeat of Russia by Japan, although making an alliance with Russia more of a possibility, made the actual need for an alliance less important.

This alliance with Japan was followed in 1903 by a French suggestion that led to the Entente Cordiale in the following year. France suggested that an Anglo-French alliance would assist Britain in holding Germany in check and would enable France to influence Russia against renewing her Far Eastern dreams at Britain's expense.

Germany remained committed to Austria, who was now her only ally in Europe. If Germany failed to support Austria and the Austro-Hungarian Empire had broken up, Germany would have been alone, at the mercy of Russia, a vengeful France and a Britain which the Germans believed wanted to destroy Germany's growing trade.

Moroccan Crisis

Following an uprising in Morocco in December 1908 the French took the step of recognising Moulay Hafid, the figurehead of the insurgency and installed him as the new 'puppet'. The new leader's tax raising attempts however, brought about a new uprising. He requested French help at putting down this challenge and France sent troops. Germany, realising that France was, in effect, setting up a protectorate, wanted compensation in return for her potential losses under such an arrangement. Whilst negotiations over the level of compensation were taking place, Germany sent a gunboat, the SMS Panther, to the coast of Morocco which had the effect of increasing tensions. Germany stated that the sending of the Panther was to protect German interests, but there can be little doubt it was to challenge the French and apply pressure during the negotiations. [5]

Britain was concerned over these negotiations. A German requirement for a naval base on the Moroccan Atlantic coast would have been a major threat to Britain's trade routes to South Africa.

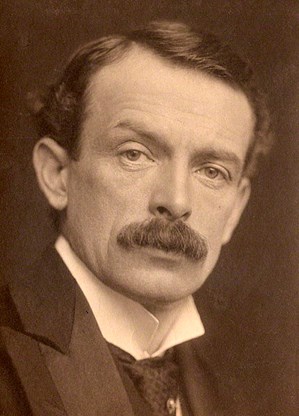

David Lloyd George, in 1902

Britain protested to Germany over the sending of the Panther and tensions increased as no German reply was forthcoming. Prior to making a scheduled Mansion House Speech on 21 July 1911, David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, discussed the situation with Sir Edward Grey. Between them they ensured the otherwise routine speech ended with a significant threat directed at Germany, to the effect that Britain would not stand by whilst her interests were prejudiced.

Henry Wilson thought that a war would come about because of German reaction to the speech and plans for war were progressed in both France and Britain. McCullough suggests that, had Britain not taken the lead in escalating the tension between France and Germany, they may have patched up their differences. It is difficult to see how this argument can be sustained when McCullough maintains, elsewhere in the book, that due to Alsace and Lorraine these two countries would never see eye to eye. McCullough states that "Agadir was a significant milestone on the road to the First World War ... violent press campaigns in France, Germany and Britain excited public opinion". [6]

Naval Race

As an island nation Britain had traditionally relied on the Royal Navy for defence. The expansion of the Empire during the 19th century created an extra role for the Navy – that of the protection of the trade routes that were used by the vast British merchant fleet.

In June 1914 Britain's merchant fleet (in terms of gross tonnage) represented over 43% of the world's total. The second largest merchant fleet was Germany's, representing 12% of the world total. [7]

Whilst the German merchant fleet was growing to support the expanding German economy, and that alone caused unease in Britain, what really caused concern was the expansion of Germany's Navy. McCullough, through the use of selective statistics, suggests that, between 1895 and 1904, Britain instigated the arms race between the navies: Britain launched 36 battleships and added more tonnage than France, Russia and Germany combined. [8]

Misuse of statistics can be used to support any range of arguments but, using McCullough's own statistics, it can be seen that despite his arguments to the contrary, German naval expansion was a threat to Britain, especially in the period 1900-1905.

In numbers of battleships launched:

Germany Britain

1895-99 4 20

1900-05 14 16

In 1906, Britain launched HMS Dreadnought, a design so advanced it was said that it made all earlier battleships obsolete. Other nations soon copied the principle behind Dreadnought and, by the outbreak of the war, there was a world total of 51 Dreadnought type battleships. Of these, Britain had 22, with Germany the closest competitor with 15. [9]

Admiral Jackie Fisher (appointed British First Sea Lord in October 1904) was aware of the threat posed by a modern and rapidly expanding German Navy and pressed his government to assign more money towards expanding the Royal Navy. He often went further than merely demanding money, suggesting in 1904 that Britain should launch a pre-emptive strike on the German Navy. This may have seemed an attractive proposition in some quarters, as it would have destroyed the German Naval threat and also destroyed the economic threat caused by the competition from the world's second largest merchant fleet. However, this proposition was not taken seriously by the Government and seems to have been a tactic of forcing more money into shipbuilding. There were further naval scares in subsequent years, such as the one in 1909 when Reginald McKenna, the First Lord of the Admiralty, predicted that by 1912, Germany would have 17 Dreadnoughts. This proved to be almost accurate, as the figure was reached a year later, in 1913.

McCullough suggests that the Admiralty browbeat successive governments into pouring ever increasing amounts of money into the Royal Navy using, firstly, concerns over the size of the Russian and French navies and, after 1904, the German Navy. He goes on to say that Britain was keen to deny the Germans the right to own a navy, and the naval arms race was at Britain's instigation. The statistics show, however, that from a standing start Germany created a navy that was truly capable of challenging the Royal Navy and, despite Britain actually outbuilding the Germans, the margin of superiority narrowed alarmingly in the years preceding 1914.

Military conversations with France / Relations with France

Although never a formal military alliance, the Entente Cordiale of 1904 did result in conversations between Britain's military and their opposite numbers in France. These conversations started in December 1905, after the First Moroccan crisis. Colonel Repington (military correspondent for The Times) was used in the first instance as the intermediary, so that the Government could state that no official communications were taking place.

The conversations came to a number of conclusions. Admiral Fisher's plan for the Royal Navy to land part of the Army on Germany's Baltic coast was sidelined in favour of the plan to land the BEF of six infantry divisions in France to operate on the left of the French Army.

Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Minister, wanted France to leave naval concerns to Britain (Britain could, on her own, deal with the German Navy). This had two benefits – firstly the possible strengthening of the French navy (a future challenge to the Royal Navy and our empire) was therefore avoided and secondly it gave us only a limited liability in a continental land war.

The military conversations were extended in 1912 to cover naval matters. It was agreed that France would take responsibility for the defence of the Mediterranean, thus allowing British naval strength to be concentrated in Home Waters. By controlling the North Sea, Britain was thus able to guarantee France's northern coast, hence the references in Grey's speech on 3 August 1914 to trade routes through the Mediterranean and our need to protect France's coast from any German naval threat.

The military conversations were not revealed to the cabinet until 1912. The conversations were explained as not committing Britain to a military alliance with France; however, there was an exchange of letters between Grey and Paul Cambon, the French ambassador in London. Within the letters was a statement:

"...if either Government had grave reason to expect an unprovoked attack......it should immediately discuss with the other whether both Governments should act together....and what measures they would be prepared to take in common". [10]

Whilst this gave no undertaking, it was evidence of Britain's intention to act in concert with France. The lack of a formal treaty allowed Asquith to tell Parliament in March 1913 that Britain was not under an obligation to send a military force to the continent. This was true as far as it went but clearly the military conversations had been taking place on a practical level for a number of years.

There has been much debate over the years as to whether the conversations amounted to a commitment to go to war alongside France in 1914. On balance it would seem that no such obligation existed. The situation in 1914 is summarised by K M Wilson who states: [11]

"When war came there was no obligation on the British government springing from the military conversations themselves....."

He goes on to assert that the problem was that the conversations had been pursued with no alternative plan and the inflexible foreign policy gave Britain no choice but to put into effect the plans made by Henry Wilson and other officers in the conversations that had taken place.

Trevor Wilson concludes that the decision to send the BEF was not based on a commitment, moral or otherwise, but upon self-interest. [12] It could not be in British interest to allow German domination of Europe. There may have been a case for sending the BEF if Britain had misled the French into believing she would support them come what may. The French, however, were not so naïve as to base their entire strategy on the arrival of the BEF. It could not have been supposed that French plans were going to collapse for the want of six British infantry divisions plus a cavalry division. If plans were likely collapse, again there may have been a strong case for there being a need to send the BEF but as the Kaiser observed, the BEF was contemptibly small.

In his speech to Parliament, Grey touched on the moral issue:

"....and to say we would stand aside, we should, I believe, sacrifice our respect and good name and reputation before the world...."

In short, the violation of Belgian territory became a useful peg onto which was hung the moral reason for going to war, but did Britain have to do this?

Commitment to Belgium?

In 1839, Britain had been a co-signatory to the treaty guaranteeing Belgium's neutrality but there has been much debate if this in itself constituted an obligation on Britain to go to war to defend Belgium. [13]

Prior to the war, Belgium was nervous of being attacked by Germany, France and Britain. This nervousness extended to Britain: a theory surfaced in 1904 from Lord Esher, [14] in which he suggested that Germany would find it vital to absorb Holland – this is presumably reflected in Grey's speech when he warns of Dutch and Danish independence.

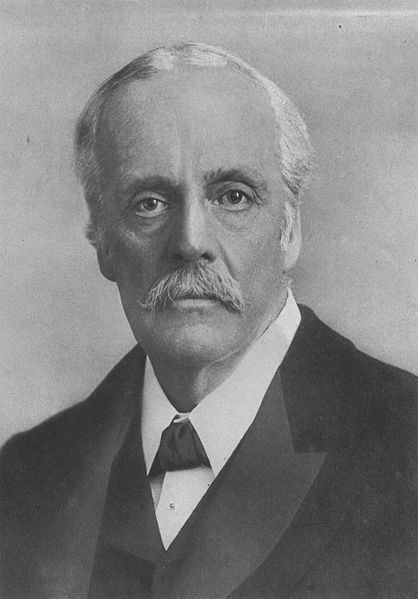

Lord Esher

To ensure Belgium was on the Entente side, France urged Britain to recognise Belgium's annexation of the Congo; this was recognised on 27 June 1913.

There was also a realisation by the French that they could not afford to be the first to violate Belgium's neutrality. In 1912, Joffre suggested attacking Germany through Belgium, [15] but was instructed that Germany must violate Belgian neutrality first in order to avoid difficulties with Britain.

All of the above indicates that there was a strong argument that Britain had a commitment towards Belgium. On the other hand, Guinn quotes Lord Salisbury (British Conservative Prime Minister 1895-1902): [16]

"Our treaty obligations will follow our national inclinations and will not precede them......"

This shows that the leader of the traditional 'war party' was stating that it would not be necessary to go to war over Belgian neutrality. Clearly the 'commitment' is open to interpretation. Grey referred to it in his speech to Parliament on 3 August 1914. (He had asked both Germany and France if they intended to respect Belgian neutrality.) He did not say in his speech "we have an obligation to maintain Belgian neutrality"; it must be presumed that he would have said this if he felt it was true because the whole tenor of the speech was justification for war. Instead, he made an oblique reference to the commitment by saying, "....we would not bargain away whatever interests or obligations we had in Belgian neutrality."

Balkans

By 1908, the new 'Young Turk' regime wanted to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia and Herzegovina. To prevent this, Austria annexed these provinces; Russia supported this move in return for Austrian support for Russia's demand for the Dardanelles Straits being opened to Russian warships. The Serbs reacted angrily to this annexation, looking for Russian support, which was not forthcoming due to their Dardanelles agenda.

The fact that neither France nor Britain was happy for Russia to have access via the Straits and did not support this Russian move may well have changed European history. Due to the lack of French and British support, [17] Russia changed her position and gave support to the Serbian protest. Hostilities seemed likely but Russia was not strong enough to go to war and the Austrian annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina took place.

Had Britain and France allowed Russia to make a treaty with Austria, Serbia, without Russian backing, despite her increased militancy, would not have dared to stand by whilst elements within her government and military plotted the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

Conclusion

Asquith, Grey and Balfour took the British Liberal Party in a new direction and the party had a more militaristic outlook after Campbell-Bannerman was replaced. [18] Had pacifist Liberals been running the party, war may have been avoided. On the eve of war, Asquith was unable to keep a totally unified cabinet [19] but nevertheless took the vast majority with him, contrary to the traditional Liberal anti-war position.

The orthodox Liberal position was one allowing free trade, with no desire to build the British Empire any further. This did not mean they were content to see the Empire crumble and they were obviously concerned about a militant Germany which also had the second biggest merchant navy and had been pursuing a naval strategy, which could only have been intended to challenge Britain's supremacy.

On the other side of the channel, France was never going to rest until she reclaimed Alsace and Lorraine. It was France who instigated the alliance-building spree, forming alliances with Russia and Britain. War was inevitable with Germany both holding Alsace and Lorraine and unable to prevent France forming alliances. If Germany had taken a step back and allowed France to have these provinces back, thus forming an alliance with France and Russia, this alliance (with or without the Entente Cordiale) would have left Britain's empire at risk. It was therefore important for Britain to form a strong alliance with France to preserve the source of British wealth, the Empire.

Whilst Britain had discussed where to place the BEF in the event of a war with Germany, there was no formal agreement to go to war. Equally there was no real reason for Britain to defend Belgian neutrality, but could Britain have stepped aside and not become involved?

This course of action may have kept Britain out of the immediate conflict but would have led to an equally dangerous position. If Germany had won, Britain would have had no one with which to form an alliance (the traditional way in war for Britain); but, equally, if France had won, what value would then have been placed on the Entente Cordiale by France and Russia?

Finally Grey, towards the end of his speech, touched on the two issues that probably troubled the politicians more than others: trade and prestige.

It is easy, in hindsight, to pass judgement on the decision for war. Grey certainly stated in his speech that he thought it would be a costly war. No one could have known how costly, in terms of human, financial and social suffering it would prove to be. Nevertheless, while acknowledging it would be costly, the politicians decided that a high price would be worth paying in order to keep Britain at the head of the Empire, generating wealth and with her prestige in the eyes of the world intact.

Article by David Tattersfield

[1] Sir Edward Grey's speech to the House of Commons, 3 August 1914.

[2] Edward E. McCullough, How the First World War Began. The Triple Entente and the Coming of the Great War of 1914-1918 (Montreal: Black Rose Books,1999), p. 170

[3] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p. 24

[4] Beryl J Williams, 'The Strategic Background to the Anglo-Russian Entente of August 1907', Historical Journal vol 9 no 3 (1966), pp. 360-373

[5] Bentley B Gilbert, 'Pacifist to Interventionist David Lloyd George in 1911 & 1914 – Was Belgium an Issue', Historical Journal vol 28 no 4 (1985). Pp. 863-885.

[6] McCullough, How the First World War Began, pp. 150-154

[7] John Ellis and Michael Cox, The World War I Databook (London: Aurum Press, 1993), p.252

[8] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p. 104.

[9] Ellis and Cox, The World War I Databook, p.251

[10] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p. 176.

[11] KM Wilson, 'To the Western Front: British war plans and the military entente with France before the First World War', British Journal of International Studies, 3 (1977), pp.151-168.

[12] Trevor Wilson 'Britain's Moral Commitment to France in August 1914', History 64 (1979), pp. 380-390.

[13] Wilson, 'Britain's Moral Commitment' pp. 380-390.

[14] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p.161

[15] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p. 175

[16] Paul Guinn, British Strategy and Politics 1914 to 1918, (London: Clarendon Press,1965). p. 5.

[17] McCullough, How the First World War Began, p. 267

[18] Guinn, British Strategy and Politics 1914 to 1918, p.10.

[19] KM Wilson, 'The British Cabinet's Decision for War, 2 August 1914'. British Journal of International Studies, 1 (1975), pp. 148-195.