The Cavalry at Monchy-le-Preux

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Cavalry at Monchy-le-Preux

The Battle of Arras started on 9 April, Easter Monday, 1917. The most famous action in this battle is the storming of the heights of Vimy Ridge by the Canadian Corps on the left of the British attack. Success elsewhere on the front was good, if not quite so spectacular. Cyril Falls (who wrote the volume of the Official History covering 1917) stated:

Easter Monday of the year 1917 must be accounted, from the British point of view, one of the great days of the war. It witnessed the most formidable and at the same time most successful British offensive hitherto launched.

What is less well known are the subsequent stages of this battle. The Battle of Arras (which included the First, Second and Third Battles of The Scarpe, plus the First and Second Battles of Bullecourt) lasted from 9 April to 16 May and was conducted largely by the British Third Army under General Allenby. It was, in terms of the daily attrition rate, the most costly British offensive of the war. The Battle cannot be examined in depth in this short article but it may be appropriate to look at one of the relatively few cavalry actions that took place in the First World War which took place during the battle.

Monchy-le-Preux

South of the positions captured by the Canadians at Vimy Ridge and dominating the centre of the front attacked stood the village of Monchy-le-Preux. This important position held the key for further success. The village stood on high ground approximately five miles south-east of Arras. Because the village dominated the countryside for miles around, it gave superb observation for artillery fire. Whoever held the village would be able to control the battlefield. It was vital for the British to take this position. Possibly due to the unexpected success, or possibly due to the ‘fog of war’, the advances made on 9 April were not followed up on 10 April. It was a situation that the cavalry may have been able to exploit, the Germans were disjointed and their lines were, in places, broken. Unfortunately, the main body of British cavalry were held too far back and were simply unable to take advantage of the fleeting success offered.

Above: Cavalry moving forward past a trench held by British infantry near Monchy-le-Preux, 13 April 1917. IWM (Q6412)

11 April

One unit of cavalry was able to play a small part in the day’s events. The Northamptonshire Yeomanry was a pre-war territorial unit. In May 1916 it was the cavalry unit selected to be the VI Corps Cavalry Regiment, and was therefore on hand when VI Corps (positioned in the vital area just south of Arras) made its attack. The Northamptonshire Yeomanry, together with the Corps cyclist unit was put under the orders of the 37th Division. After waiting west of Arras they were ordered to advance, and ‘B’ Squadron galloped towards Fampoux. Jonathan Nicholls in his book about the battle Cheerful Sacrifice quotes Serjeant Bertie Taylor who was part of this charge:

The shells were dropping fast and thick, then we came to some slit trenches and we just jumped these with the horses squealing – just like a hunt! Then we passed through our leading troops and I remember seeing a lot of Scottish soldiers just lying there, machine gunned….Soon we got into Fampoux….we came under shell fire and one of our officers, Captain Jack Lowther – who had an enormous nose – had the end of it sliced off by a piece of shrapnel. Well, we laughed didn’t we, but he got off his horse and picked up the end of his nose and wrapped it in his handkerchief!

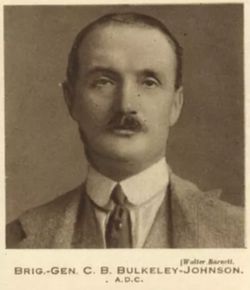

Despite the failure to exploit the success of the opening day, an all out effort was made on 11 April to keep the pressure on the Germans. The defenders had used the 48 hours since the start of the battle to good use and had reorganised; the German position in Monchy had been reinforced by the 3rd Bavarian Division. By now the British Cavalry had moved up, and the 3rd Cavalry Division had been instructed to support VI Corps. The division’s 8th Cavalry Brigade (under Brigadier Charles Bulkeley-Johnson) and 6th Cavalry Brigades were in position.

The infantry of VI Corps attached at dawn on 11 April, and by 7.30am elements of both 15th (Scottish) and 37th Divisions were holding positions in and around Monchy village, however, the German artillery was still intact.

Brig. Gen. Bulkeley-Johnson, ordered his brigade to advance to the north of, and beyond the village; the 10th Hussars and Essex Yeomanry of 8th Brigade were to circle around between Monchy and the River Scarpe. In view of this advance, 6th Cavalry Brigade was instructed to conform with the advance of the 8th Cavalry Brigade - the 3rd Dragoon Guards of 6th Brigade headed south of the village. These three regiments moved forward over prepared trench crossings at around 8.30am.

According to David Kenyon’s PhD Thesis “British Cavalry on the Western Front 1914-1918”:

Emerging south of Orange Hill they advanced at the gallop, in line of troop columns, with one troop advanced as scouts. An advance in brigade strength like this was a rare enough sight to make a significant impression on the watching infantry. Capt. Cuddeford of the Highland Light Infantry (15th Division) was witness to this advance:

During a lull in the snowstorm an excited shout was raised that our cavalry were coming up! Sure enough, away behind us, moving quickly in extended order down the slope of Orange Hill was line upon line of mounted men covering the whole extent of the hillside as far as we could see. It was a thrilling moment for us infantrymen, who had never dreamt that we should see a real cavalry charge, which was evidently what was intended.

Above: Battle of the Scarpe. British cavalry resting on the Arras-Cambrai Road, April 1917. IWM (Q2032)

Jonathan Nicholls takes up the story:

And so, at 8.30am a squadron of the Essex Yeomanry under Lieutenant Chaplin, followed by a squadron of the 10th Hussars under Captain Gordon-Canning, each with a section of machine gunners, cantered smartly round the southern slope of Orange Hill. They made a magnificent sight…Towards the northern edge of Monchy they came under fire; several saddles were suddenly emptied…galloping headlong for the village while German shells exploded all around them.

Nicholls quotes from Trooper Clarence Garnett, who was one of the machine gunners attached to the Essex Yeomanry:

I was riding a little horse called Nimrod and leading another with a pack saddle no his back loaded with boxes of machine-gun ammunition. We had not gone far when a huge shell burst on my right. Someone yelled “Garnett’s pack horse has broken its leg!” Our corporal, Harold Mugford shouted at me to keep going but the pack horse fell, and as I was holding on to him so tightly he pulled me out of the saddle. I let go and managed to stay on Nimrod, regaining my balance, but then my saddle slipped under his stomach. I rode on, hanging on for dear life, on his bare back. All the rest of the column had left me and seeing a huge Hawthorn tree, I got behind it and adjusted the saddle.

Above: British cavalry resting alongside the Arras-Cambrai road. IWM (Q2031)

A Victoria Cross earned

Harold Mugford was to be awarded a Victoria Cross later that day, his citation in the London Gazette 26th November 1917 reading:

On 11th April 1917, under intense fire, Lance-Corporal Mugford got his machine gun into a forward very exposed position from which he dealt very efficiently with the enemy. Almost immediately his No.2 was killed and he was severely wounded. He was ordered to go to a new position and then have his wounds dressed but this he refused to do staying to inflict severe damage on the enemy with his gun. Soon afterwards a shell broke both his legs but he still remained with his gun and when he was at last removed to the dressing station he was again wounded.

Click here for further details of the VC awarded to Harold Mugford.

Above: Harold Mugford, VC

Meanwhile the Northamptonshire Yeomanry were still in the area and – although they did not have orders – joined in the charge on Monchy. Nicholls quotes again from Serjeant Bertie Taylor:

We got on top of the rise and there it stood, red bricks showing – Monchy! The snow was laying thick and I remember at this point some of our horses collapsed, buckling the swords of their riders. We extended into one long line, a bugle sounded and we charged! Over open ground, jumping trenches, men swearing, horses squealing – a proper old commotion! The bugle sounded three times – and we had come under quite heavy shell fire and some of the saddles had been emptied. Bur the horses knew what to do better than we did, and galloping by me came these riderless horses…one came flying past me with half his guts hanging out… The riderless horses were leading the charge. Eventually I caught up with our officer, Mr Humphriss, who was riding a few yards ahead when a shell exploded just beneath his horse and split him like a side of beef hanging up in the butcher’s shop. Both horse and rider were killed instantly. Next we got into the village and the streets were so narrow that tiles from the roofs were raining down on us – that’s what caused a lot of injuries.

Nicholls quotes again from Trooper Garnett, who, having previously taken refuge behind the Hawthorn tree, now arrived in Monchy:

By now there were a few of us and shelling had become very heavy, so the officer ordered us to lie down under the shelter of a wall…I had not been there long when a light shell came through the gap in the cottages and cut down the officer and most of the others. Nimrod was terrified and he reared up violently, dragging me along the street for some yards until I was forced to let go. I never saw him again after that.

The German artillery pounded Monchy. Kenyon describes:

As the morning wore on, the situation in the village became grim, especially for the exposed horses. Indeed Lt. Swire of the Essex Yeomanry had to be specially detailed for the task of shooting wounded horses in the crowded streets. Col. Whitmore reported at 11.10am:

Have sent several messages conveying all information … What remains of those regiments are holding on to the north-east, east and southern exits of the village. Require both M.G.s and ammunition. Am afraid we have had many casualties. Counter-attack expected. Col. Hardwick and several officers wounded. Reinforcements required as reserve. Majority horses casualties.

Kenyon continues:

Meanwhile on the right of the 8th Cavalry Brigade, 6th Cavalry Brigade advanced as far as the Monchy-Wancourt road south of Monchy, with 3rd Dragoon Guards leading. The regiment advanced with ‘B’ Squadron in front (Capt. Holroyd-Smith), with one troop of the squadron in line and the remaining three troops in line of troop columns behind, followed by ‘C’ Squadron (Maj. Cliff). On reaching the road, the Dragoons came upon a party of Germans attempting to dig in, in front of four guns. These troops fled, leaving the guns.

Brigadier-General Killed

Around 9.00am, in an attempt to assess the situation, Brigadier-General Bulkeley-Johnson (who was the officer in command of the 8th Cavalry Brigade) advanced with his staff as far as the Monchy-Fampoux road. According to Davies and Maddocks in Bloody Red Tabs:

The General wanted to know what the situation was. Captain Cuddeford informed him that the enemy in front had been strongly reinforced during the past 24 hours and that the enemy was concentrating round the village of Pelves, down by the river. The General thought that he would like to see something of the enemy dispositions for himself. Captain Cuddeford told him that if they were spotted by German snipers it would be necessary to dodge them by sprinting diagonally from shell hole to shell hole. The General insisted on going on against the Captain’s advice, and perhaps being rather old for that sort of active dodging or, as it seemed to Captain Cuddeford at the time, too dignified to get well down at the sound of a bullet, he would persist on walking straight on. They had not gone far when one skimmed past the Captain and struck the General full on the cheekbone….They succeeded in dragging the General to a shell hole but he died as they were getting him there.

Above: Brigadier-General Bulkeley-Johnson's headstone at Gouy-les-Artois Communal Cemetery Extension

Conclusion

Due to its prominent position, the Germans tried to recapture Monchy on 23 April, but the village was defended with great heroism by troops of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. The use of cavalry in this action on 11 April was notable, but not unique. Further cavalry actions would take place in 1918 in France, and others would take place in Palestine, but the opportunities to use cavalry in this way were fleeting.

Above: Members of the British Cavalry huddle together, next to their horses. The horses and men keep close to one another in an attempt to keep warm, and shelter from the snow and wind. Many of the horses are covered in snow. (National Library of Scotland)

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

3rd Cavalry Division and Northamptonshire Yeomanry

Losses on 11 April 1917

6 Cavalry Brigade

1st (Royal) Dragoons – 3 men killed in action. Private J Jordan (buried at Feuchy Chapel British Cemetery), Private E McIntyre (also buried at Feuchy Chapel British Cemetery) and L/Cpl G Rankeillor (who has no known grave).

3rd (Prince of Wales' Own) Dragoon Guards – 2 officers and 20 men killed in action. 19 have no known grave and are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the missing. Those with known graves are Lieutenant CH Newton-Deakin (Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery), Private W Archer (Monchy British Cemetery) and L/Sjt L Ash (Tilloy British Cemetery).

North Somerset Yeomanry – 4 men killed in action. L/Cpl CE Baker, Private AJ Chivers, L/Cpl W Deane and Private CF Tambling (all buried at Feuchy Chapel British Cemetery).

8 Cavalry Brigade

Brigadier-General Charles Bulkeley-Johnson is buried in Gouy-les-Artois Communal Cemetery Extension.

10th (Prince of Wales's Own Royal) Hussars – 27 men killed in action. 23 of these men are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the missing apart from Private HG Holliday (Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery), Private C Gent, Corporal R Norman and Private JM Ransome (Tilloy British Cemetery)

Essex Yeomanry – 29 men killed in action. All are commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the missing except Trumpeter AHW Stowell who is buried at Feuchy Chapel British Cemetery.

VI Corps Cavalry Regiment

Northamptonshire Yeomanry – 9 officers and men killed in action. These include Lieutenant AF Chaplin (Beaurains Road Cemetery) (date of death stated to be 10 April), Lieutenant JEJ Brudenell-Bruce (Duisans British Cemetery), Private HH Smith (Monchy British Cemetery) plus a further two officers and four men (including 2/Lt EV Humphriss, mentioned above) who are all commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the missing.

Further Reading

Barton, Peter and Banning, Jeremy Arras – The Spring offensive in panoramas including Vimy Ridge and Bullecourt (London: Constable, 2010)

Davies, Frank and Maddocks, Graham - Bloody Red Tabs – General Officer Casualties of the Great War, 1914 to 1918 (London: Leo Cooper, 1995)

Kenyon, David - Horsemen in no man's land (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2011)

Kenyon, David - British Cavalry on the Western Front 1914-1918 (Ph.D Thesis, Defence College of Management and Technology, 2007)

Nicholls, Jonathan - Cheerful Sacrifice (London: Leo Cooper, 1990)