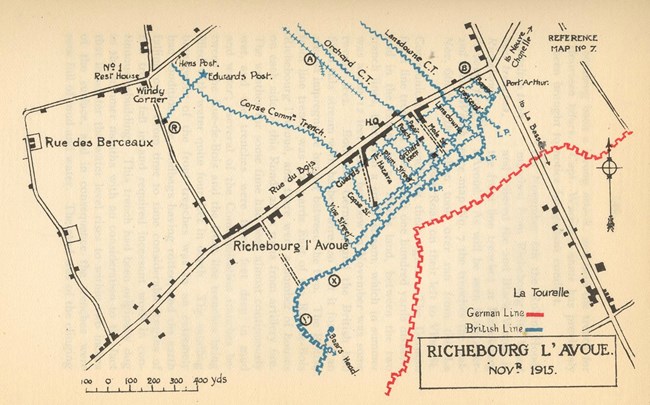

The Chatsworth Rifles raid at Richebourg

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Chatsworth Rifles raid at Richebourg

An ideal way to obtain an understanding of the First World War is through reading the memoirs of those who served in the conflict. Examples of these are numerous, Goodbye to All That (Robert Graves, 1929) and Old Soldiers Never Die (Frank Richards, 1933) are well known, but not so There’s a Devil in the Drum (John Lucy, 1938). All of these were first published before the Second World War. It is very rare for a good quality memoir to surface in the 21st Century. Luckily a significant memoir (written in the 1930s but never previously published) has just come to light; it is appropriate to use an extract of one of the chapters of this book below. This was published as “Joffrey’s War” in 2013.

Geoffrey Husbands ("Joffrey" of the title of the book - this was his nickname) was a well educated young man who joined up slightly under age as a Kitchener volunteer in the 16th (Service) Battalion, the Sherwood Foresters (Chatsworth Rifles). After undergoing training in the UK, Geoffrey’s battalion was sent, in early 1915, to the Western Front and spent some time holding trenches and generally acclimatising to trench warfare. The level of detail that can be found about the training regime and the early days of trench warfare (“pre-Somme”) is of great interest, but the first time the Chatsworth Rifles are in serious action is described in Chapter 39 (the book comprises 60 chapters in all), and is fascinating for the way the author brings the people to life. The action in question took place on 12 July 1916 and Husband's account of this is reproduced below, with permission from the copyright holder.

The Trench Raid at Richebourg

The fateful night of the raid arrived: a dark and moonless night. I was on guard after “stand-to” that evening and about half past ten or eleven there was a sound of tramping feet in the communication trench and the raiding party came up and filed along to take their place at the staring point of our Company’s front.

A weird and fiendish crew they looked with faces and hands blackened to render them less visible; the whites of their eyes gleaming eerily in contrast, and bayonets glinting in the glare from the last dying embers of the cook’s fires.

Till midnight things remained fairly quiet but as the hour passed and we changed guard the calm of the night air was broken. With an ear-splitting crash the barrage opened out and from behind our lines a deadly rain of projectiles burst on Fritz's line. Then a brief almost momentary pause, and it was lifted on to his second line while mingled with the crash of the shells came the duller boom of bursting bombs.

Fritz was not long in starting to retaliate; from his line went up a frenzied succession of signal lights - green and orange rocket flares, signal of SOS to the artillery. Then …whizz…crash…whizz, whirr..r.r. and the wicked scream of shells and screech of shrapnel bursting above our own parapet.

The men on guard crouched down in corners of the bays or crept underneath the wooden fire steps for such shelter as they provided; while the actual sentries expected certain death each moment.

The German artillery gave us a terrible pasting and we learnt what a bombardment feels like. A horrible, helpless feeling it was; here was no enemy to be countered by rifle fire or cold steel; no man-to-man struggle where strength or valour might avail; it was the essence of modern war, man pitted not against man but against metal. The strong, the weak, the fearless, the coward were alike helpless - the sport of chance and fate.

Our little band sat tight in the dugout and trusted to Providence that there would be no direct hit to wipe us out.

Outside the darkness was lit up by the blinding flashes of exploding shells - whizzbangs and overhead shrapnel and the heavier high explosive. Some tore screaming over the parapet to explode in the marshy ground behind with devastating roars; some fell short, burying themselves with thunderous crashes in the soil of no-man's-land; shrapnel burst twelve feet above us in the air and scattered its deadly pellets and splinters in a hail of metal, rattling on iron and wood all around incessantly. Acrid, choking fumes filled the air - we smelt powder that night, as the old phrase has it, if never before. ‘That's a close one by George!’ as the dugout timbers tremble and creak at a terrific concussion and ear-splitting crash, and the loose earth trickles from the splitting sandbags to the floor, while outside the boards of the trench are littered again with bits of sandbag, shrapnel splinters and wood chippings. ‘Another blinking iron foundry come over!’ says someone and at the next boom and crash ‘That's blown a whole bay in, I dare bet’. ‘Pity the poor sentries.’ ‘God help poor sailors on a night like this!’

We are feeling far from flippant in reality but we must keep up our spirits somehow and when Death and Terror are stalking hand in hand down the lines it is well to keep them at arms length by whatever means one can. Die we shall, if we must; but better to die with a jest or a curse than with a weakling’s whimper.

So the ordeal went on: time ceased to have any meaning, was it minutes, hours or an eternity it lasted?

Meanwhile Jock Simpson was playing the part of a true hero. In the height of the bombardment reckless of the shelling he patrolled the trench unshaken and iron nerved, cheering the sentries and setting a magnificent example of fearlessness. Other officers might go to earth but Jock remained throughout the strafe with his men.

‘All right in here?’ he asked cheerily if a little anxiously, stooping down to peer through the dugout door as he passed us. ‘All right here, Sir,’ we chorused in reply, every man the better for that brief cheery word and the genuine solicitude it expressed. ‘That's an officer for you,’ we said admiringly. ‘Good owd Jock, he deserves a VC if anyone does’ - and we meant it.

It is a somewhat ironic comment on the system of conferring military honours and decorations when one reflects that Jock left our Battalion undecorated - not even the MC so often "dished out with the rations", as the BEF used to say, while others we knew who in our eyes had done little or nothing, received the official tokens of approval.

But to return to the raid. ‘Hark, the barrage's shifting again! They'll be coming back now’ and thus saying, we listened to our artillery shortening their range again and giving cover to the returning raiders. Very soon there was a noticeable slackening in the intensity of the firing on both sides, and the shells at length came over sullenly and spasmodically in contrast to the furious incessant crashes before. The worst of the strafe was over.

And now the raiders had tumbled back into their own line and began to stray along the trench. One look at the first party was enough to tell us how the game had gone.

It was by no means the triumphal return that had ended the raid at Givenchy the previous month. Losses had been heavy and there was some bitter complaint of an inefficient barrage and of men laid out by our own guns.

Down the trench passed the boys, spotted with blood, stained with sweat and dirt, a grim enough sight. We sat in the dugout mouth and took in the news as it filtered through in brief and terse sentences.

‘Illsley's lost a leg’ ran the whisper, and soon the leather-lunged songster of No.10 was borne past groaning on a stretcher. ‘Lieutenant Cholerton's done for, I reckon’ - and there follows another stretcher with a silent blood-stained form lying on it covered by a ground sheet - the Bombing Lieutenant seemed to have had half his face shot away.

But next came the worst Job's messenger of all in the person of Joe Annable. ‘How's things gone, Joe?’ was the query. Annable halted, and with bitter curses and a voice half-choked with emotion told us his story.

‘Poor old Archie Quartley's gone, and it's a bloody shame too.’ We in the dugout exchanged startled looks: one old pal's premonition had been fulfilled all too correctly then! A bitter story it was that Annable poured out. How Quartley had been hit in coming away; how he, Annable, and one or two other No.11 lads had helped him through the wire and had stumbled back, half carrying half supporting him across no-man's-land; how they fell and tripped and dodged and crawled and rested and set off again; how Archie was faint with loss of blood and could go no further. Just then, said Annable, a little band of men including a Sergeant, came up with them and he begged them to help with their burden and they wouldn't stop. ‘Thought too much of their own dirty hides,’ said Joe with fierce curses. ‘That took all the heart out of Archie,’ he went on, ‘he'd been struggling on like, till then and he heard those ..blank's.. refuse and that ..blank.. of a Sergeant and he says "that's done it, lads: leave me and get on wi' it: that's what yer own pals do for you" sey poor old Archie and he drops. We got into the trench to get some help but he was done for before we could get him in.’

It was a sad blow for us who had been his pals and as we saw Annable depart, our hearts were heavy with his tidings.

The raid, if it could be called a success at all, was a dearly bought one and its cost out of all proportion to its result.

One of "A" Company's young officers, who was leading a party, was reported to have jumped first of his squad into the trench, bayoneted two Germans and then been killed himself - all in the first few moments of the struggle. This Subaltern was one who arrived with the Battalion about the same time as Messrs. Simpson and Benner. An original soul, he was also reported to have told his Platoon to call him Harry - so at least, said rumour.

George Lessons of "C" Company had not returned and was said to have been seen hanging in the German wire. (It was many weeks later that we heard that actually he was captured and in a German prison camp but doing fairly well.)

Tom Moseley had been "wired" also, but his were mere scratches - minor injuries that luckily were cured after a day or two at the Field Ambulance.

Nor had we come through the night scatheless in the line. I lost another pal that night besides poor Quartley. A shell had made a direct hit on the roof of a shelter in which were Lieutenant Stevens and several men taking cover. Charlie Jackson and Deverill were of the number, and poor Deverill had received the full effects of the shell burst. They said that both arms and legs were shattered and that he lingered in agony crying to someone to finish him off with a bullet. Poor lad! Only a few hours before we had met and been chatting of our old Redmires companionship. Now all that was over and I the poorer by the loss of a good-hearted, cheery friend. Charlie Jackson, mercifully escaping any wound, was nerve shattered and had to be sent out of the front line for rest. It was a miracle that the whole of the dugout's occupants were not killed.

Another loss had befallen No.11 Platoon in the person of Jim Foster. A whizzbang crashed through a shelter and blew the top of his head off. Altogether, the morning after the raid was a gloomy one for us. The losses we had suffered reduced our strength appreciably and I seem to recollect that Nos. 10 and 11 Platoons were merged for trench duty and went down together to the supports at Tube Station when the four days in the front line were ended.

Notes

Harry (the officer of A Company) was Second Lieutenant Harry Spencer Seabrook who is commemorated on the Loos Memorial.

Loos Memorial to the Missing at Dud Corner Cemetery

Besides Lieutenant Seabrook, the raid also cost the lives of Second Lieutenant N.C. Dawson who is buried at Bethune Town Cemetery and Private H.B. Clements.

Bethune Town Cemetery

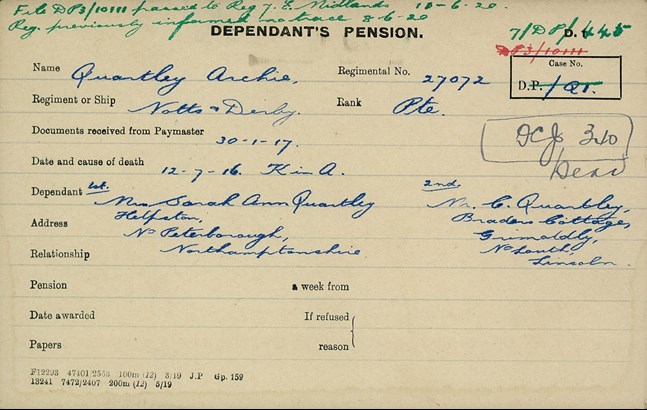

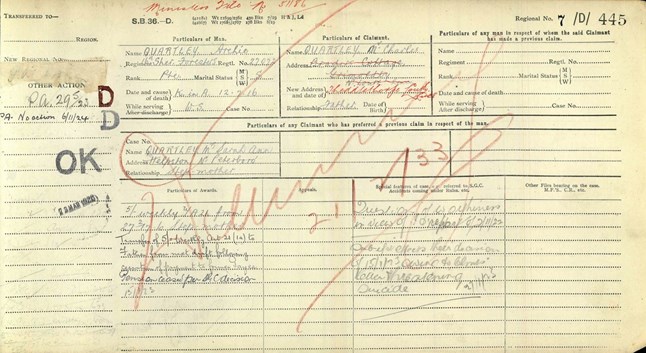

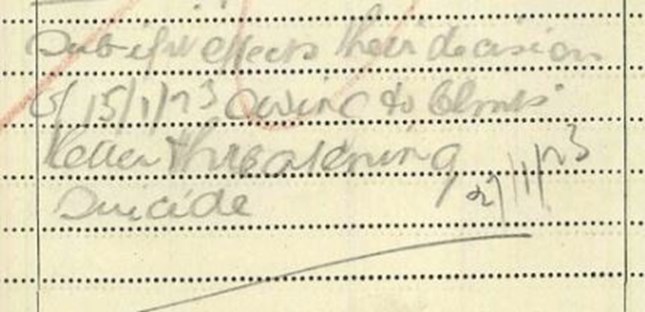

In the preceding chapter, the Memoir described how Private Archie Quartley had had a premonition of his death which came true. The father of Quartley (Charles) claimed a pension which was eventually terminated in 1923. The record of this claim suggests that the Ministry of Pensions received a letter from Charles threatening suicide, which adds a further level of detail to this sad episode.

Above: the ledger relating to the pension claim from Charles Quartley (Archie's father)

Above: A close up of part of the above ledger.

The other soldier mentioned by name as being killed is Jim Foster who is buried at Le Touret Military Cemetery, as is Arthur Deverill, who, although not mentioned in this passage, is frequently mentioned earlier in the memoir.

The final battalion fatality from this action is Private JH Walklate who is also buried at Le Touret Military Cemetery

Le Touret Military Cemetery, Richebourg-L'Avoue

Second Lieutenant J.R. Cholerton who is mentioned as having half of his face shot away, survived. Second Lieutenant C.J. Hart and 10 Other Ranks were wounded and two Other Ranks were posted "missing believed killed", one of whom was George Lessons, who was actually a Prisoner of War. Sergeant A.G. Hildreth was awarded the DCM. Sergeant E. Gilbert, Private J. Hutchinson and Private T.E. Pegg were awarded the MM.

Second Lieutenant ‘Jock’ Simpson survived until July 1918 but was killed on the 13th of this month, and is buried at Nine Elms British Cemetery.

Joffrey’s War

The two editors of the book are the late Bob Bushaway, and Dr John Bourne, who is a Vice President of the WFA.

A presentation given by Bob Bushaway, only weeks before his death is on the WFA's Youtube channel here: The Making of a World War

Also on the WFA's Youtube channel are a number of presentations by John Bourne, one of the most popular being this: 1918: The fall of eagles

Article by David Tattersfield