The First Phosgene Attack on British Troops : 19 December 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The First Phosgene Attack on British Troops : 19 December 1915

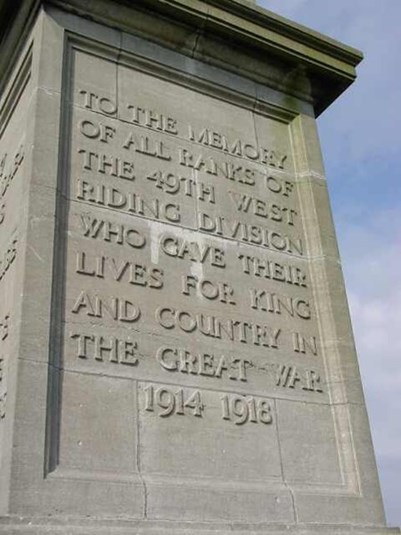

The first use of phosgene gas against British troops by the German army took place on 19 December 1915. The gas attack took place north of Ypres where the 49th (West Riding) Division was in the line.

This attack had been ‘given away’ when a German prisoner had been interrogated. As a result an artillery barrage on the German trenches was ordered on 15 December, however, a shortage of artillery shells meant that the 49th (West Riding) Division's guns were unable to disrupt the planned attack.

At 5 a.m. on 19 December a parachute flare was seen to rise from the German lines and at 5.15 a.m. red rockets were observed. These were so unusual that British sentries gave the alert. Shortly afterwards, a hissing noise was heard and an unusual smell noticed. On the left flank, in the 49th (West Riding) Division area, no man's land was only 20 yards wide in places. An amount of incoming small-arms fire was received from the German trenches before the gas discharge.

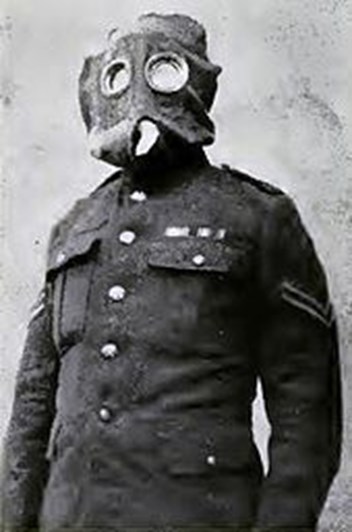

Above: A crew of a Vickers Machine Gun wearing the anti-gas helmets of the day.

The German gas discharge on the front from Boesinghe to Pilckem and Verlorenhoek was followed by twenty raiding parties, which had been instructed to observe the effect of the gas and to take prisoners. Only two patrols were able to reach the British line and several parties suffered losses to British return-fire

The gas formed a white cloud about 50 feet in height and lingered for half an hour before the wind blew it away. The results of this gas attack were felt over a large area - originally discharged on a 3 miles frontage - the gas cloud moved for about 10 miles almost as far as Bailleul.

Although British troops were by that time equipped with anti-gas helmets, these helmets had not been treated to repel Phosgene gas

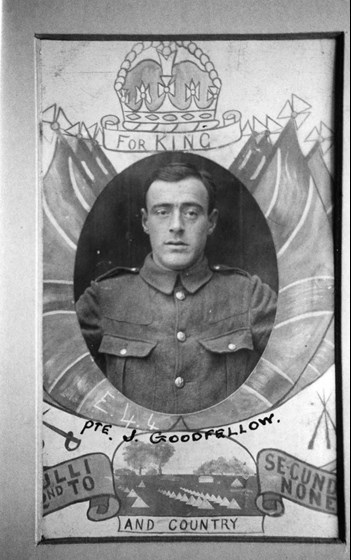

Above: A British soldier in a P or PH helmet in use on 19 December

One of the battalions that were badly affected by the attack was the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I. The Battalion’s War Diary for 19 December gives an excellent description of events:

“4.50am: A hissing noise like a fast running motor car was heard in the German lines. Very shortly after the presence of cylinder gas, said to be Fossgene [Phosgene] was detected in the air. Warning was given [to put on anti-gas helmets] and rapid fire opened on the enemy’s parapet with rifles and machine guns. ‘S.O.S. Gas’ was sent to the artillery who immediately opened fire. No infantry attack was made [by the Germans] but later a German patrol numbering about ten was seen advancing towards our trenches. Rifle fire was opened on them and they dispersed, only one man being seen to regain the German trenches....”

The news of the attack was heard back at home. Many of the men from the battalion were recruited in Dewsbury, and the local newspaper published the following on 1 January 1916:

“Whilst the list of casualties to the local territorials as a result of a German gas attack on December 19th is serious, we are asked to deny a rumour that many men are dead.”

The War Diary of the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I. records one officer and 23 other ranks died of gas poisoning, plus six other ranks killed in action. Fatalities recorded by the CWGC suggest that on 19 December the battalion lost 18 men, whilst in the 1/4th Duke of Wellington's 25 men were killed. On the subsequent three days a further 14 men from the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I. died of their wounds.

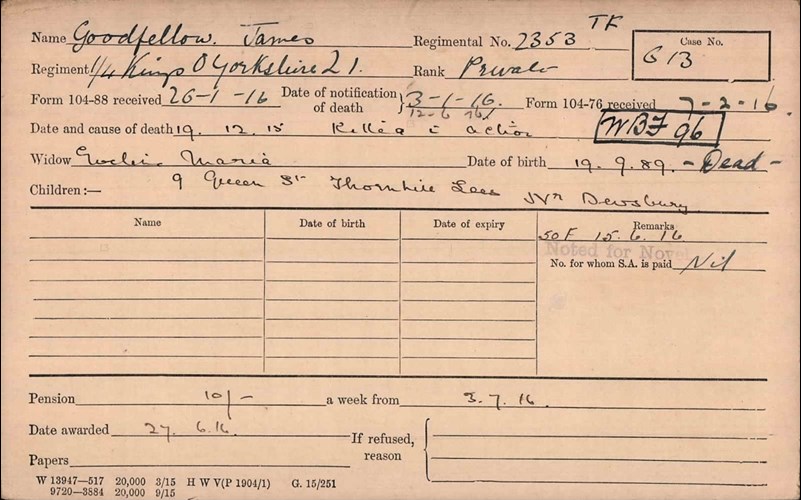

One of the men of the 1/4th K.O.Y.L.I. who died at this time was James Goodfellow. Jim was employed as a stacker by Hirst & Gill, mungo manufacturers of Calder Wharf Mills, Ravensthorpe; he was married and lived with his wife Eveline in Bridge Street, Ravensthorpe. A pre-war territorial, he arrived in France on 13th April 1915.

James Midgley Goodfellow was born in Chapeltown, Leeds in 1888. Seemingly known as 'Jim', his wife received letters of condolence from the battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Haslegrave, and also from Mrs Haslegrave.

Jim is buried at Bard Cottage Cemetery.

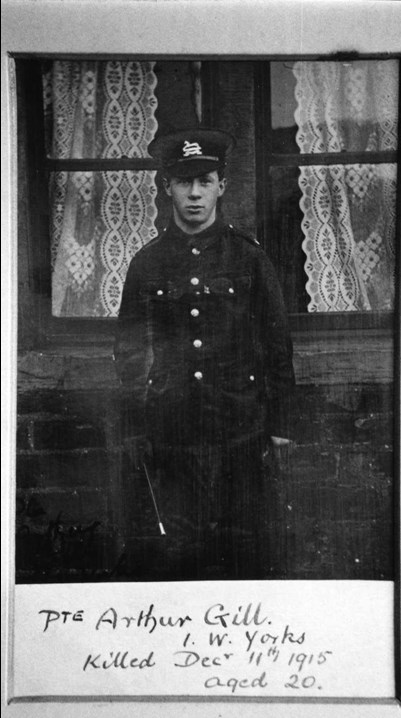

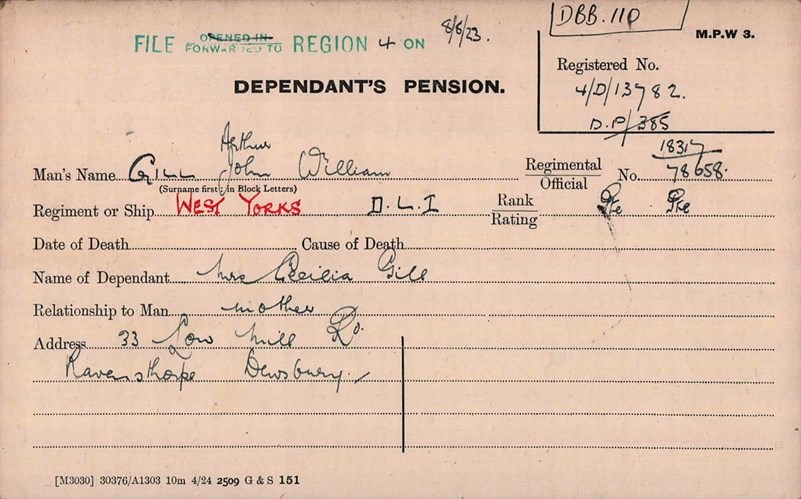

The attack did not just affect the 49th Division. On the 6th Division front to the right the opposing trenches were about 300 yards apart. Although a ‘regular’ division, the 6th also had wartime recruits within its ranks, such as Private Arthur Gill of the 1/West Yorkshires.

Above: Private Arthur Gill. The date of death written on the original photograph is incorrect.

The division was ‘stood to’ during the gas attack on the 19th but was not as seriously affected as the units to the north. During that evening the Germans heavily shelled the 6th Division, and ‘D’ Company of the 1st West Yorkshires had two of its dugouts destroyed, causing eighteen casualties. It is likely that Arthur Gill was one of these casualties.

Sister M. Wharton of the 17th Casualty Clearing Station - which was located at Remi Sidings, Lijssenthoek - wrote on the 20th December to Arthur’s mother, Cecilia: “I very much regret having to send you very bad news of your son who was admitted last evening suffering from internal injuries caused by the falling in of a dug out. His condition is most critical. You may rest assured everything will be done that can be done for him. He sends his love and best Christmas wishes.”

Sister Wharton wrote again the next day to say that Arthur had died that morning (the 21st) at 11am.

Arthur Gill is buried at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

There are no memorials to mark this attack that took place just before Christmas 1915, but the memorial to the 49th (West Riding) Division stands adjacent to Essex Farm Cemetery, on the canal bank.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association