The Loss of HM Yacht Iolaire 1st January 1919

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Loss of HM Yacht Iolaire 1st January 1919

Hogmanay 1918 and many families in the Western Isles awaited with great anticipation the imminent return of husbands, fathers and sons after four long years of war. Such was the demand to get returning servicemen home, the mailboat ‘Sheila’ could not cope with the demand and therefore the Admiralty drafted in the Yacht Iolaire to assist. But when the Iolaire arrived at Kyle at 4pm on 31 December, she collided with the pier as a result some refused to board her.

Above: The Admiralty yacht HMY Iolaire under the name 'Amalthaea'

Image credit: Ness Historical Society, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

The Iolaire finally left the port of Kyle of Lochalsh on the Scottish mainland late on 31 December 1918. On board were around 254 returning servicemen, many of whom had served in the Royal Naval Reserve, two base sailors and a crew of 24. Therefore around 280 men crammed aboard.

At 1.55am on 1 January 1919, the Iolaire was approaching Stornoway harbour when, in appalling weather and sea conditions, she hit the infamous ‘Beasts of Holm’ so close to harbour were these rocks that those on board would have seen the lights of Stornoway.

Above: Stornaway in the Western Isles

Above: Lying close to the entrance of Stornoway Harbour these rocks are the ‘Beasts of Holm’

Two lifeboats were launched but were smashed upon the rocks by the mountainous seas and as the yacht heeled heavily to starboard, many jumped into the sea but were dashed against the rocks. Many of those aboard could not swim and those that could were hampered by their greatcoats and boots.

Seaman John F Macleod (image below) from the Port of Ness managed to secure a rope, and around 40 men were saved as a result, but a total of 181 islanders, the 2 returning base sailors and 18 of the crew perished.

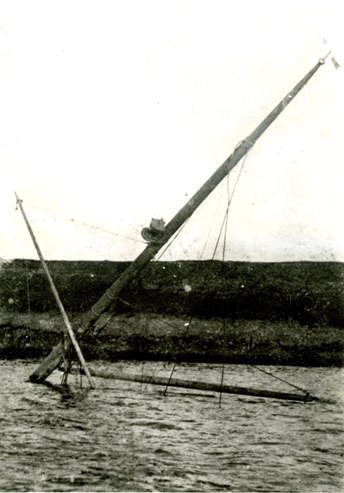

Above: The mast of the Iolaire remained visible after the sinking

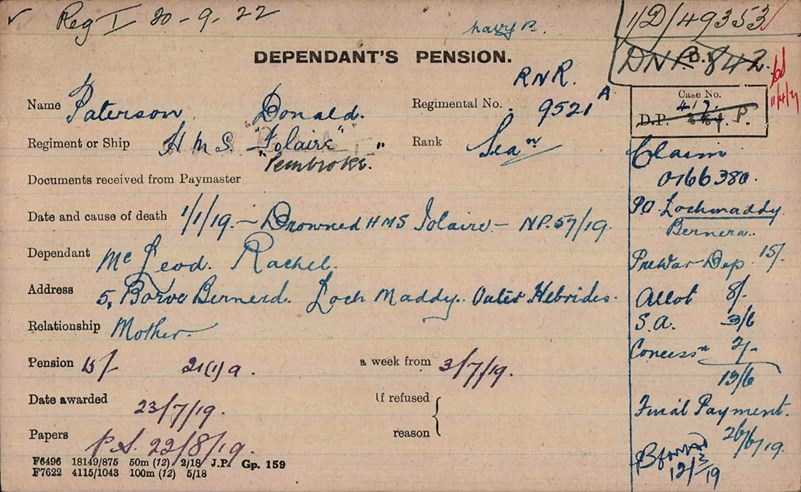

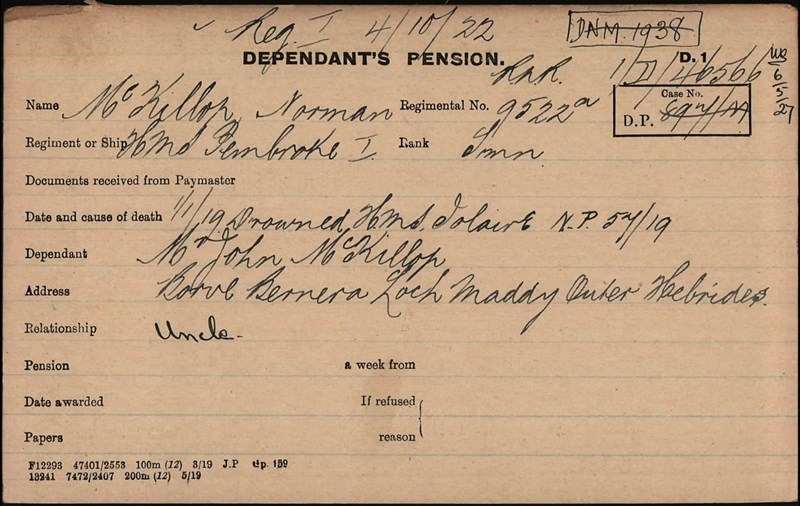

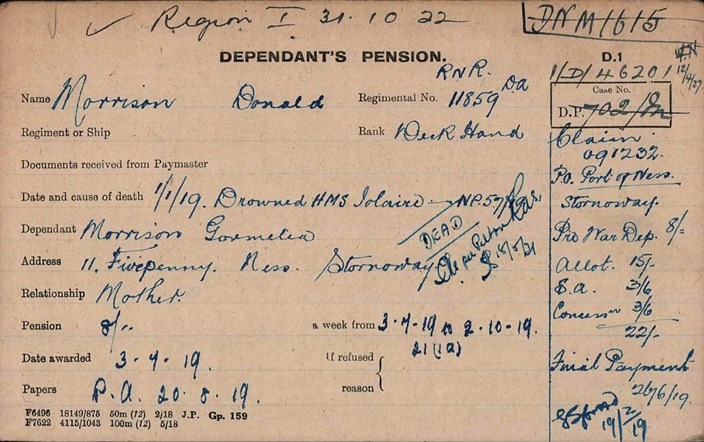

Pension cards for many of those lost can be found in the records preserved by The Western Front Association. Two young men from Borve on the island of Berneray were amongst those lost.

These two lads have consecutive service numbers, having enlisted together on 25 September 1918, both aged 18. They took the decision to board the Iolaire, rather than await the boat for Tarbert due on 1 January. Norman’s body was not recovered but Donald is buried in Berneray Burial Ground.

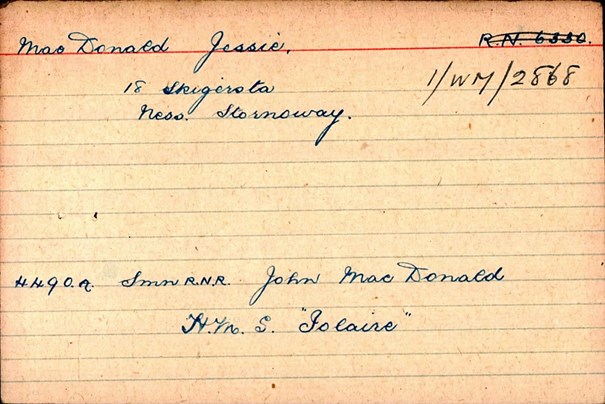

Seaman John MacDonald came from Ness – a community which lost 23 men from the Iolaire.

John married Jessie Finlayson on 18 October 1918, during his last leave at home. Although no mention is made on the Pension Card, his widow Jessie was initially refused a pension on the grounds that there was no proof that her marriage had been consummated. However the pension was later granted.

Seaman John Murray, also from Ness, was one of the oldest servicemen lost that night. He left a widow, three sons and a daughter and is buried at Ness (St Peter) Old Cemetery.

Another Ness casualty of the Iolaire had previously served in 2 Seaforth Highlanders, Seaman Donald Morrison had enlisted at Fort George on 30 September 1908, serving in the Special Reserve until his mobilisation on 1 September 1914.

He was severely wounded in the back at St Julien near Ypres on 26 April 1915, when many of the battalion were killed in action. Donald was discharged in September 1915 but later enlisted in the Navy in August 1916.

Other casualties of the Iolaire had survived torpedo attacks in which the ship on which they were serving was lost.

Seaman Kenneth MacPhail from Arnol had enlisted in the Royal Naval Reserve in 1911 and was mobilised on 2 August 1914, serving on HMS Prince of Wales until May 1916. However, on 31 October 1917 he was aboard SS Cambric when it was torpedoed and sunk in the Mediterranean Sea by U-35. One of only five survivors, his Service Record indicates that he clung onto wreckage for 36 hours until washed ashore. He was admitted to the military hospital in Cherchell, Algeria before being repatriated and later served on HMS President III.

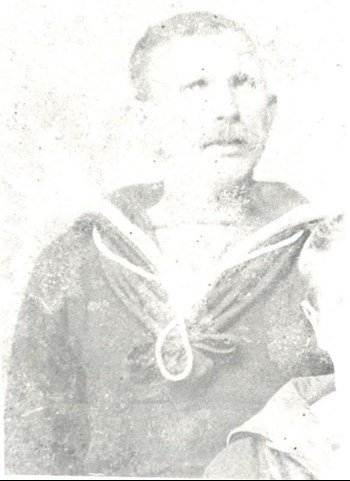

Seaman Murdo Maclean from South Bragar had served on SS Inverbervie when it was torpedoed and sunk by UC.14 in the Mediterranean. Also from South Bragar, Seaman Malcolm Macdonald had survived the explosion in Halifax, Nova Scotia on 6 December 1917 whilst serving on HMS Calgarian. Both were lost in the tragedy, just yards from the shore of their homeland.

Above: Malcolm Macdonald

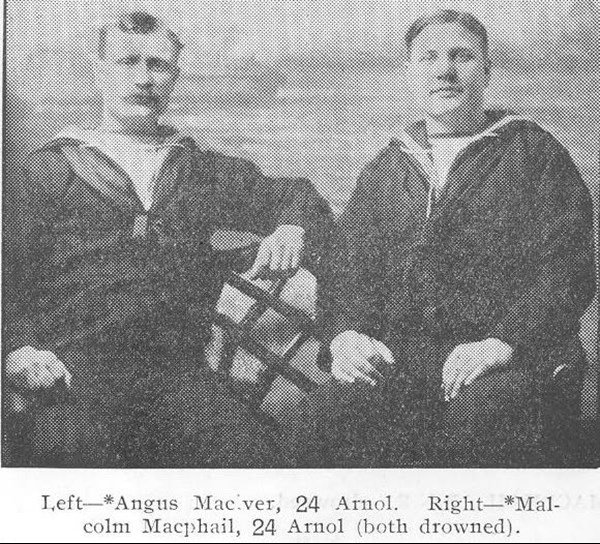

For some families, the loss was not just one son, but two.

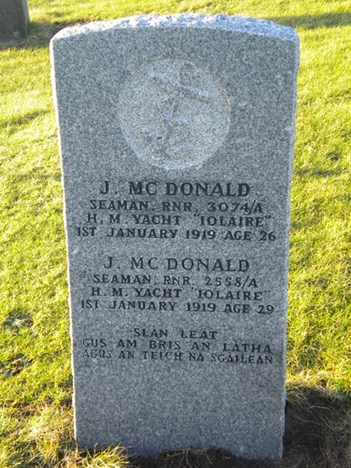

Donald and Murdo MacDonald from Swainbost were travelling home together. A family story relates that Donald, a strong swimmer, reached the shore but returned to the wreck to search for his brother. Neither survived, with Donald’s body never found whilst Murdo was buried at Ness (St Peter) Old Ground. From North Tolsta, brothers Donald and Malcolm Macleod were both lost from the Iolaire. From Sheshader, two brothers perished - both named John but known as John Snr and John Jnr Macdonald.

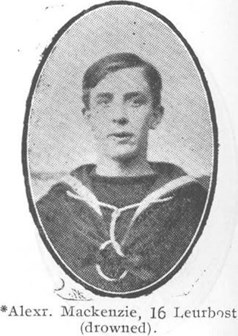

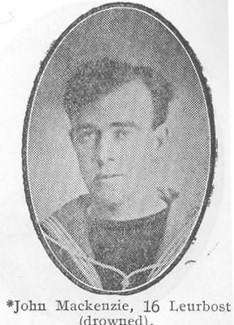

And also from Leurbost, brothers Alexander and John Mackenzie were lost.

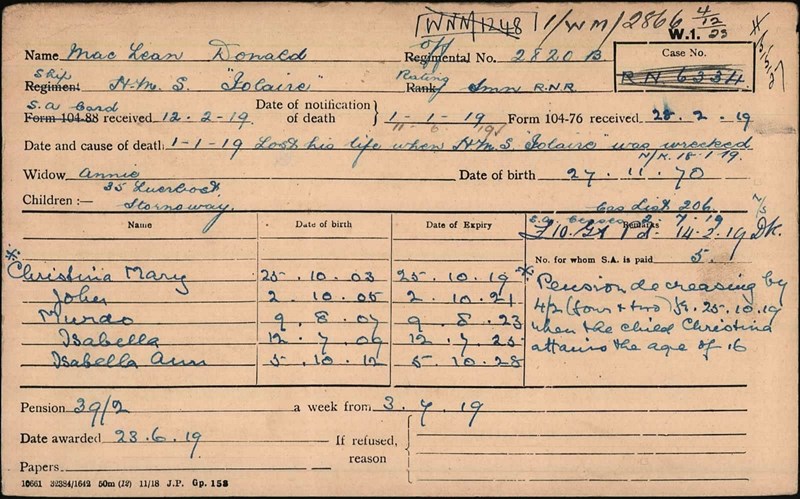

Tragedy followed tragedy for the family of Seaman Donald Maclean of North Lochs.

Donald, a married man with seven children, had served in the Royal Naval Reserve since 1905 and was mobilised on 4 August 1914. His eldest daughter, Catherine, collapsed at the news of the tragedy and died a few days later. Both she and her father were buried together in Crossbost Cemetery.

Of the crew of 24, 18 were lost, the youngest of whom was Signal Boy David McDonald from Aberdeen, aged 17. He is buried at Sandwick, Stornoway.

Above: Sandwick Cemetery graves.

Commander Richard Mason of HMY Iolaire also perished but although his body was recovered according to local press reports at the time, there is apparently no record of any burial place.

For the islanders, the loss of the Iolaire was devastating, not least because the tragedy left an estimated 250 children without a father. For decades, many could not even speak about the events of that night, such was the pain and grief still felt. Many also felt anger at the way in which the Naval Court of Inquiry was convened on 8 January 1919 within days of the tragedy, with survivors, many of whom were still traumatised by events, summoned to attend. The refusal of the Admiralty to publish the findings of the Inquiry further inflamed the feelings of the bereaved. The findings were not published until 50 years later and were locally generally felt to (wrongly) exonerate the actions of the officers involved. Furthermore, the actions of the Admiralty in allowing the wreck to be sold and later broken up in the late 1920s enraged the islanders and those who had lost loved ones. And for those that had survived, many experienced such a sense of survivor guilt that some emigrated from the islands in the inter war years, further decimating small and fragile communities. It would not be until 1960 that a memorial was erected to those lost.

Above: Iolaire Memorial obelisk

Article by Jill Stewart and Robert Stone