The Manchester United v Liverpool match fixing scandal of 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Manchester United v Liverpool match fixing scandal of 1915

Association football had, despite the outbreak of the First World War, not been suspended by the time the season ‘kicked off’ in the summer of 1914. This brought much criticism on clubs and indeed players. The season 1914-15 was destined to be the last until the 1919-20 season.

Above: A photo of the 1909 FA Cup Final Bristol City (in blue) v Manchester United (white with a red 'V'). Manchester Utd won 1-0 with the goal by Sandy Turnbull.

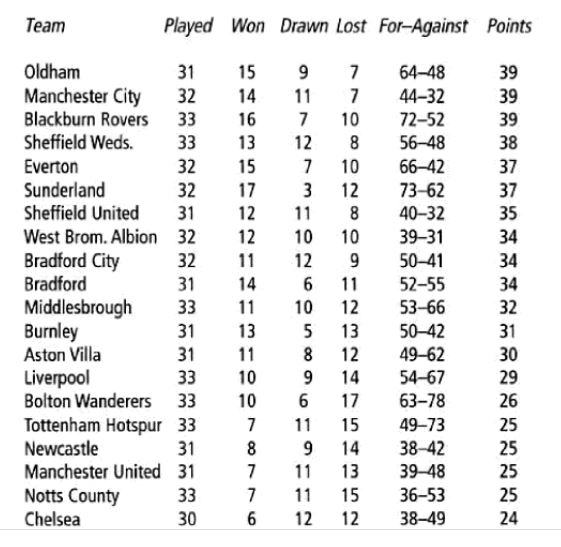

In the first division, the ‘big’ Easter fixture of 1915 was the match between Manchester United and Liverpool. Liverpool had nothing to play for – they were to finish the season in 13th place (out of 20 clubs) but Manchester United were much more in danger of relegation – eventually finishing just two points ahead of Tottenham Hotspur who were relegated.

Above: A league table for late March 1915. Manchester United are only a point clear of relegation (one club was relegated in those days) - they had played more games than those beneath them.

Clearly Manchester United needed the points to survive, and Liverpool players were probably aware that they would end up ‘mid table’.

With the future uncertain due to the war which could potentially end their footballing careers, a number of Liverpool and Manchester United players met several times at The Dog and Partridge and other pubs in Manchester to discuss arranging (or ‘fixing’) the outcome of the forthcoming encounter between the two teams.

Above: Manchester Utd 1911-12

Liverpool captain and former Manchester United player Jackie Sheldon was joined in the conspiracy by teammates Thomas Fairfoul, Bob Pursell and Tom Miller. From Manchester United were players Alexander (Sandy) Turnbull, Enoch West and Arthur Whalley.

Odds of a Manchester United win by 2 goals to nil were available at 8/1. It was therefore arranged that that would be the final score in the match that was scheduled for Good Friday - 2 April 1915.

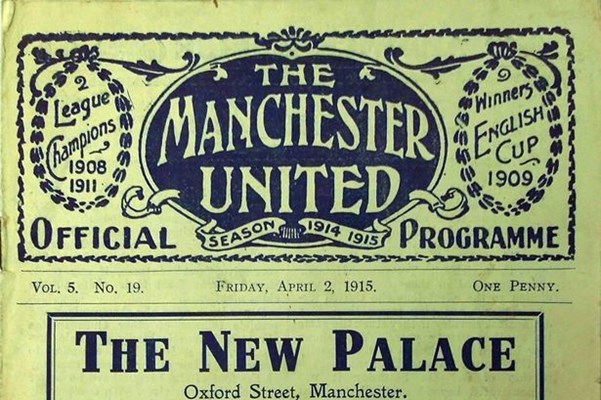

Above: A matchday programme of the 2 April encounter between Manchester Utd and Liverpool

The final whistle saw the match end (to the surprise of few on the pitch) in a 2–0 win to Manchester United, with George Anderson having scored both goals. However, the match referee and some observers noted Liverpool's lack of commitment during the game – they had even missed a penalty. It was also noted that when Liverpool’s Fred Pagnam hit the Manchester United crossbar late in the match, his teammates publicly remonstrated with him.

Manchester United's Sandy Turnbull didn’t actually play in the game, but others who had met in the Dog and Partridge did take part.

After the match

“A Moderate Game – Manchester United Get Two Points From Liverpool” proclaimed the headline above the ‘Sporting Chronicle’ match report, while the ‘Manchester Football Chronicle’ had the headline “A Surprising Display” above its report.

‘The Wanderer’, reporting on the match for the latter, wrote: “Personally I was surprised and disgusted at the spectacle the second half presented. While in the ‘Chronicle’, their correspondent wrote of the play in the second half being too poor to describe”. Neither they, or any of the other reporters present voiced their opinions as to how the play was so dire, but the crowd were certainly not slow in making their feelings known, with many heard to comment amongst themselves that they felt the game was rigged. Especially after United had taken a 2-0 lead, when they did little in the way of attempting to increase it, happy to simply plod away, without putting the Liverpool defence under any form of pressure.

In the ‘Daily Dispatch’ their correspondent ‘Veteran’ wrote that West, in the second half, “was chiefly employed in the second half in kicking the ball as far out of play as he could”. So disgusted was the ‘Daily Mirror’ with the proceedings that it simply carried the result and no report. Even the ‘Liverpool Daily Post’ wrote “that a more one sided half would be hard to witness” and that Beale in the United goal went half an hour without touching the ball.

After the match, leaflets started to appear, alleging that a large amount of money had been bet on a 2–0 win to Manchester United and a notice appeared in the ‘Sporting Chronicle’ from a bookmaker, under the name of ‘Football King’, which offered a reward to anyone who could supply information on the events at Old Trafford a few days previously.

The Football Association launched an investigation and it was soon found that certain players had been involved in rigging the match. Other players, such as Liverpool’s Fred Pagnam and Manchester United's George Anderson, had refused to take part. At the hearing, Manchester United player Billy Meredith denied any knowledge of the match-fixing, but stated that he became suspicious when none of his teammates would pass the ball to him.

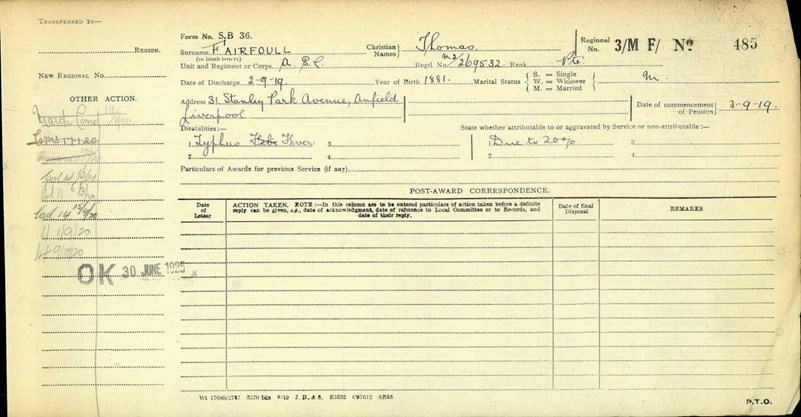

As a result of the investigation, Sheldon, Fairfoul, Pursell, Miller, Turnbull, West and Whalley were all banned from football for life.

The Liverpool Echo reported in December 1915 that "the excuse, if such it can be called, has been made that the players were tempted into the sordid business through the belief that the war would prevent football in 1915-16, and summer wages would not be the rule. But it is too paltry a claim in connection with a grave charge, and can be ignored."

Inevitably, many of these players ended up serving in the war, and following the conflict, all the players, except West, had their bans lifted by the FA in 1919 in recognition of their service to the country. (West protested his innocence, but his ban was not lifted until 1945.)

Above: Liverpool's Tom Fairfoul

Above: Fairfoul's Pension Ledger - showing football-career ending illness.

Sandy Turnbull, however, was not to benefit from the lifting of the ban, as he was killed in the war.

Turnbull

Above: Sandy Turnbull

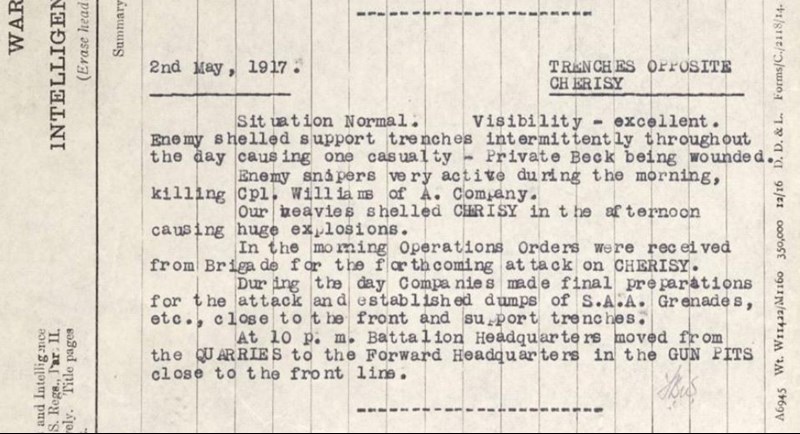

Alexander (Sandy) Turnbull enlisted in the 23rd Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment (2nd Football Battalion) but was later transferred to the 8th Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment in the 18th (Eastern) Division. It is not without note that this battalion had on 1 July 1916 kicked a football across No Man's Land. After being promoted to the rank of lance-sergeant, he took part in the Battle of Arras, and was killed on 3 May 1917 aged 32.

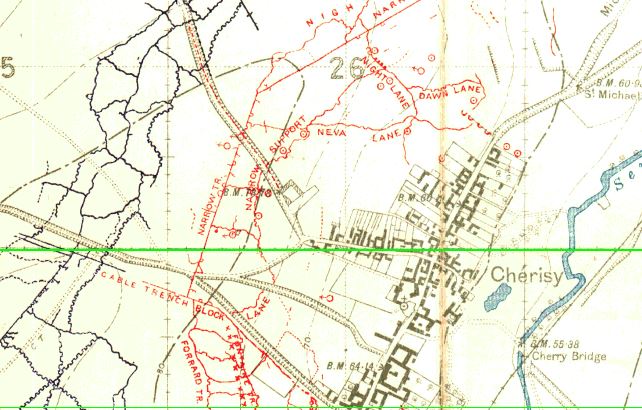

Above: The battalion attacked towards Cherisy.

Below: The view today from the road just north of 'Cable Trench' looking towards the village.

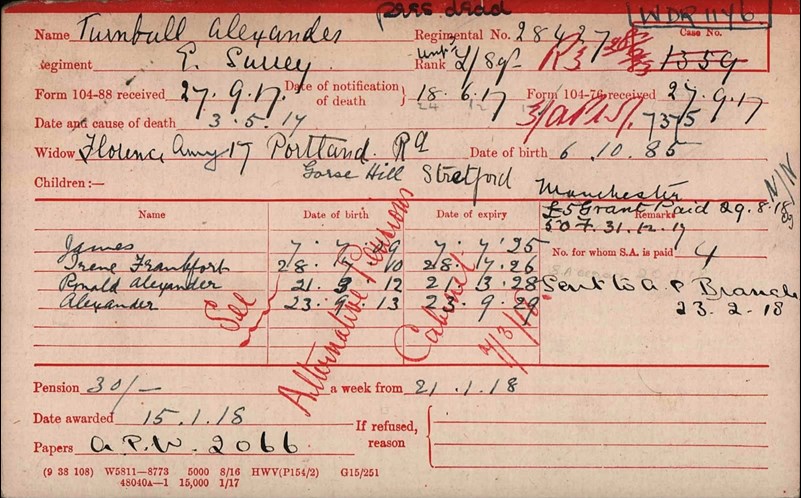

Above: The pension record card for Alexander (Sandy) Turnbull

Above: The battalion war diary describing dispositions just before the attack on 3 May.

Sandy’s wife Florence received a letter at her home at 17 Portland Road, Gorse Hill Stretford.

“I am writing to try to explain what has happened to your dear husband, Alec. He was wounded, and much to our sorrow, fell into German hands, so I hope you will hear from him. After Alec was wounded he ‘carried on’ and led his men for a mile, playing the game until the last we saw of him. We all loved him, and he was a father to us all and the most popular man in the regiment. All here send our deepest sympathy.”

Above Portland Road. Number 17 is second from the right. (c) Google Street View 2021

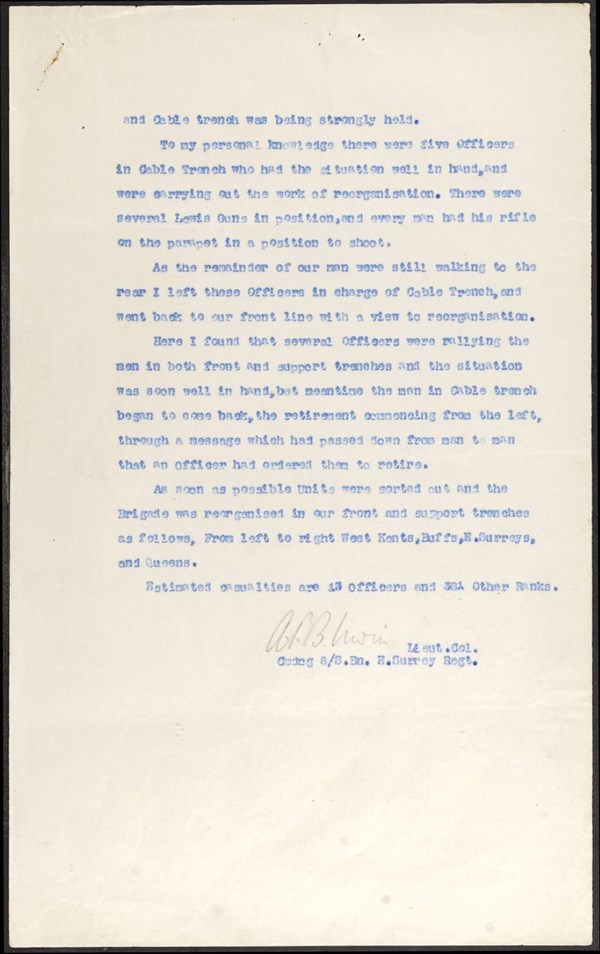

Above: The final page on the 'report on operations' from 3 May by the CO of the 8th East Surreys.

In another letter to the Turnbull home, this time in August 1918, Captain C. J. Lonergan of the 8th Battalion, who had returned to England after being held a prisoner of war, wrote:

“It was a great shock to me to hear that my best NCO, ie Sergeant Turnbull, was still missing. Of course, I knew there was no hope of him turning up after such a long period. He was one of the finest fellows I have ever met. A great sportsman and as keen a soldier as he was a footballer. He had been hit through the leg early on in the fight. When I saw him his leg was very much swollen, so I ordered him back to the dressing station. He pleaded so hard, however, to be allowed to stay on until we had gained our objective that I gave way.

Sandy was in command of a platoon. The men would simply go anywhere with him. Well. The end of it all was that, although we gained all our objectives, the division on our left did not. Consequently, the enemy got round our flanks and we had to get back as best we could. We came under very heavy machine-gun fire during the withdrawal. This was when I was hit. As I fell I saw your husband pass me a few yards away. I saw him get to the village which we had taken that morning.

There was some shelter here from the bullets so heaved a sigh of relief when I saw him disappear among the houses. I knew he could get back to our lines with comparative safety from there. I never heard anything more from him. Those who were wounded all thought sandy had got back. It was a bitter disappointment to me to hear that he had not been heard of. The only explanation I can give is that he must have been ‘sniped’ by a German who was lying low in one of the houses.

It was a rotten bit of luck. I would have recommended him from Germany, but I had my doubts whether the German Censor would allow it to come through. However, I put his case strongly when I wrote from Holland and I do hope he will get the highest distinction possible. He certainly deserves it”.

The 3 May attack by the 8/East Surreys resulted in the deaths of 98 officers and me. Sandy, as with virtually all of these men, has no known grave and is commemorated on the Arras Memorial to the Missing. He is also named on a war memorial by the side of Chester Road - not far from Old Trafford where the infamous match took place.

After the war, Sandy Turnbull received a posthumous reinstatement into the game by the Football Association.

Above: Chester Road War Memorial, Manchester

Above: The Arras Memorial to the Missing. Photographed by greentool2002 (c) 2019

Article by David Tattersfield Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association