‘The Scum of the Earth’

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘The Scum of the Earth’

In 1813 the Duke of Wellington, angered by incidents of looting amongst his army, wrote sourly: ‘We have in the service the scum of the earth as common soldiers.’ The words were harsh, but not altogether inaccurate, for the British Army had a long tradition of recruiting primarily amongst the poorest and most desperate of society.

Above: The Duke of Wellington by Francisco Goya in the National Gallery.

Fast forward a century later and little had changed.

Despite the earnest efforts of various committees and reformers to improve the lot of the soldier and make the military a more appealing career for a better class of recruit, the all-volunteer army remained perennially short of numbers.

In the Edwardian period the phrase 'it’s the workhouse or the Army' was analogous to ‘between a rock and a hard place’. Writing in the 1930s, disillusioned cavalryman Arthur Osborn of the 4th Dragoon Guards commented:

In England the ranks of the Regular Army had always been a refuge for the man out of work, the man with no friends and no prospects, for the boy who could not find a job and had neither energy nor initiative to make one for himself, for the healthy man who was not a blackguard but a failure in civil life because he could not fight successfully against his fellows in a sternly competitive world. So it followed that many ‘fighting men by trade’ are anything but ‘fighting men by temperament’.

He was not wrong: in 1913 less than half of all enlistments had any form of trade.

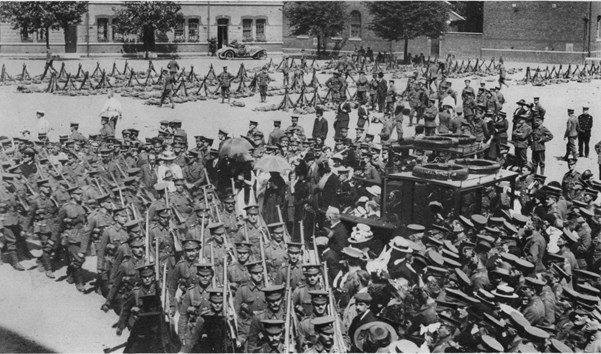

Above: Members of the Black Watch on their way to war with the BEF

Above: The Grenadier Guards who would not have taken kindly to Wellington’s unflattering description of the average soldier.

Furthermore, contrary to popular and contemporary French and German belief, the ranks of the British Army were not filled with hardened, long service veterans. The majority of Britain’s private soldiers were relatively recent enlistments, with a high proportion having less than two years’ service at the outbreak of the war.

The more experienced soldiers tended to be the reservists who were recalled to the colours in 1914. Many of these men had been out of the army for years and their standards of fitness and military knowledge varied wildly - from proud veterans still capable of 20 aimed shots per minute with a Lee-Enfield rifle, to others deemed so unfit they were initially rejected for service.

Above: Members of the Essex Regiment on 10 August 1914 in Norwich market place.

From this unpromising material the British Army was somehow able to shape a famously effective force, which pays testament to the quality of training during the pre-war period. As well as possessing advanced tactics, the Army was hugely experienced in moulding unhealthy, ill-educated young men into soldiers.

Writing after the war, John Lucy of the 2nd Royal Irish Rifles looked back aghast at the miseries of his first six months of training but took immense pride that by the end of it he and his comrades were a ‘crack squad’ who were ‘superbly fit’.

British training was enhanced by the experience of officers and NCOs. On the outbreak of war, the junior officers possessed a huge fund of combat experience gained from the hard school of colonial service, whilst 138 out of 157 infantry battalion commanders had been on active service. Company commanders were similarly experienced, and a substantial number of senior NCOs had seen action in the Boer War. Young soldiers loved and feared these ‘old sweats’ in equal measure.

Another important element to British training was the strength of the battalion system: the fierce loyalty held by soldiers to their battalion was largely incomprehensible to contemporary foreign observers, who felt that the men’s loyalty should lie with their nation.

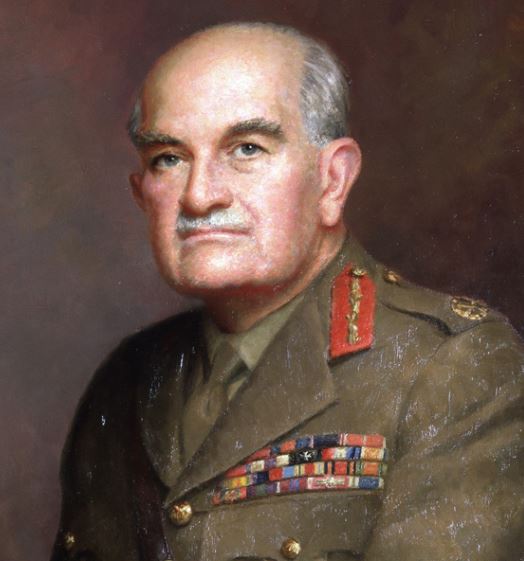

Above: Field Marshal Bill Slim, the ‘soldiers’ soldier’ who served as a junior officer in the First World War

The battalion provided something far more tangible than the abstract concept of national identity as it was both a ‘home’ and a ‘team’ for the men. The rank and file came to know their officers and formed deep friendships with their comrades. Field Marshal Bill Slim, a junior officer in the First World War who rose to command 14th Army in Burma in the Second World War, commented that the battalion system is ‘the foundation of the British soldier’s stubborn valour’.

The combination of battle-hardened leaders and the iron bonds of battalion loyalty provided the British Expeditionary Force with the tools it needed to forge its unpromising raw material into a force that would come to wear the name ‘Old Contemptibles’ with such pride.

In closing, it is well worth recalling the lesser known second part of the Duke of Wellington’s quote that introduced this piece: "It really is wonderful that we should have made them to the fine fellows that they are."

Original research and article by Spencer Jones. Edited by Dr Martin Purdy