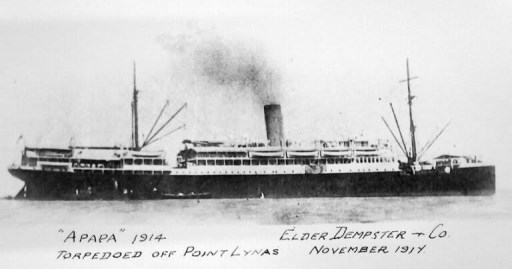

The Sinking of the RMS Apapa 28 November 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Sinking of the RMS Apapa 28 November 1917

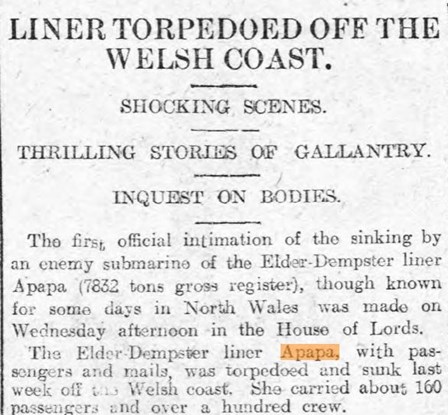

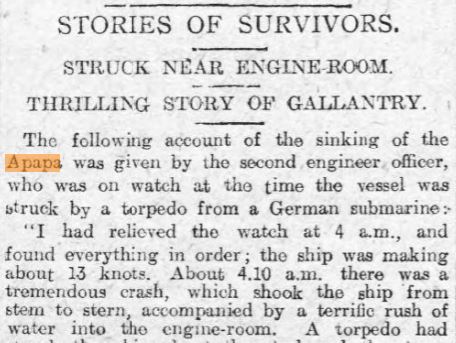

It was towards 4 o'clock on the morning of 28 November 1917 with a choppy sea running - cold, dark and wintry - that the R.M.S. Apapa, one of the 7,000 ton mail steamers of the Elder Dempster fleet, was steaming a good 13½ knots off Point Lynas, bound to Liverpool from West Africa.

Everyone was in bed; no one save the lynx-eyed officers of the watch and their men, were astir. No doubt to many on the ship the sleep that morning was one of calm contentment, for in another six hours the ship would be safely alongside Liverpool Landing Stage. She had on board 119 passengers, 132 of a crew, mails, and a full cargo of African produce. The Apapa left Sierra Leone in convoy. In due course the convoy was met by six destroyers. some of the vessels were bound for the English Channel, and the remainder - the Apapa, City of Glasgow, and Circassia - were bound for Liverpool.

Three of the destroyers accompanied the English Channel vessels, and the other three escorted the Liverpool-bound ships, and remained with them until about 6-30 p.m. on November, 27th, when they signalled that the three merchantmen were to proceed independently; the destroyers then left, probably going into Milford. The three vessels kept in company until 10 p.m., when the Apapa lost sight of the other two. She proceeded alone, making about 13½ knots, zigzagging, and rounded the Skerries in safety. In accordance with instructions received at Sierra Leone, she steered a course to pass Point Lynas at a distance of about two miles. The weather at the time was bright moonlight, with a strong westerly breeze and rough sea. The Commander, Captain James T. Toft, was on the bridge with the second and fourth officers and an apprentice. There were four look-outs, and the gun-crew were at their posts.

Suddenly the Apapa shook from stem to stern, and the passengers were thrown from their bunks. "The ship has struck something" was the cry as they rushed on deck. She was sinking, that was evident enough, but fortunately she was settling down on an even keel. The engines were stopped to take the "way" off the ship. Rockets were fired, illuminating temporarily the impenetrable darkness of that wintry morning. Captain Toft ordered the boats to be lowered away; that was a comparatively easy task while the ship maintained a fairly even keel, though she took a slight list to starboard.

The cries of women and children were heartrending and were the only sounds that broke the stillness of that early morning, save perhaps the noise of escaping steam. Close examination proved that a torpedo had rent a huge hole in the starboard side, right aft.

Most of the passengers and crew were in the boats when the figure of a man suddenly disappeared down a companion-way. His errand was one from which he never returned. He was Mr. Harragin, of the Gold Coast Customs, who was coming home with his wife to spend a well-earned rest in England, looking forward to spending Christmas in the old country. He had gone to the cabin to try and save his wife who was lying ill with black-water fever.

He made an attempt to carry her on deck, but she declared herself too ill and weak to be moved. "Very well," replied Mr. Harragin, quietly; "I will stay with you." He did so - and they passed into the "Great Unknown" together. It is a much too sacred thing to speculate upon the feelings of that hero as he sat there beside his wife, awaiting death. But what a death! Let us picture in our mind's eye husband and wife clasped in each other's arms, who knows! - maybe taking a last long embrace on this earth - and then a sudden rush of water into their cabin, and then…

When almost everyone was safely in the life-boats, and the Apapa was steadily sinking - still maintaining an even keel - a white streak cut through the water towards the ship - another explosion - columns of water shot up and swamped some of the boats, with a waterfall effect; other boats, all filled with survivors, which happened to be in the wake of the second torpedo were crashed to atoms, and alas, the occupants also.

But the worst was still to come, the second torpedo found its mark also on the starboard side, but more forward than the first. As soon as the ship was struck a second time she heeled over to starboard, lay on the surface for a second or so, and then took her final plunge, going down stern first.

In heeling over, the funnel caught a life-boat containing thirty people which, with its living freight, was sent beneath the waves. Other life-boats became entangled in the wireless aerials, while others were smashed by the masts falling upon them; thus is explained the large loss of life which accompanies this ocean tragedy.

It might be thought that along period intervened between the time when the Apapa was hit and her final plunge. As a matter of fact, from the time the ship was struck until she disappeared only ten minutes elapsed.

The remaining life-boats pulled away from the scene of the disaster, though one returned to pick up Captain Toft, who after the ship had sunk beneath him, was seen clinging to an up-turned boat. The Commander maintained, to the highest degree, that glorious tradition of British seamanship which impels a Commander to remain on the bridge of his ship until she sinks.

Six life-boats in all were undamaged and remained afloat, but owing to the roughness of the sea, they were unable to cruise round for the purpose of picking up those still struggling in the water. For about two hours the survivors drifted about, until succour arrived, steam drifters coming to their assistance, and eventually landing them at Holyhead. Captain Toft endeavoured to keep the boats together, but when the drifters arrived it was found that one boat was missing. The worst was feared, but fortunately this life-boat was picked up by a passing steamer and the occupants landed at Liverpool.

But the toll! Out of a complement of 251 passengers and crew, over 70 lives were lost, 40 of whom were passengers.

No doubt the Huns celebrated another "victory" on board their craft that morning, for it was wonderful into what extravagances their search for the destruction of innocent lives betrayed their judgment.

Source: The Elder Dempster Fleet in the War 1914-1918

Publisher

The Elder Dempster Company 1921 (73 pages)