The world’s largest pre-atomic explosion: Halifax Harbour 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The world’s largest pre-atomic explosion: Halifax Harbour 1917

Not all fatalities that occurred in the First World War were as a direct result of enemy action. There are many examples of incidents and accidents throughout the Great War that resulted in injury, loss of life or damage to property. Perhaps the most significant of these accidents is surprisingly also one of the least well known – even to this day.

As part of the effort to provide relief to Belgium, the Norwegian transport ship the SS Imo (which had been built in 1889) had been chartered by the international (but American based) organisation the “Committee for Relief in Belgium” with the intention of taking supplies from the USA to Belgium. Sailing empty from Holland to New York, she arrived for inspection in Halifax, Nova Scotia on 3 December 1917 where she was detained for a few days.

The SS Imo.

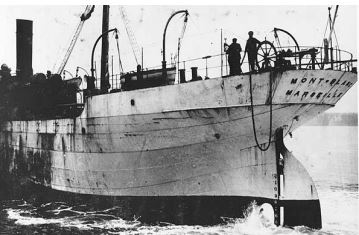

On Thursday 6 December, the French tramp steamer the SS Mont-Blanc was heading towards Halifax. Launched in 1899, she was not a particularly old vessel and had been bought by a the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, a French state-owned corporation that was responsible for a large proportion of France’s war-time shipping requirements. The Mont-Blanc, was packed full of military explosives including TNT, picric acid, benzol and guncotton; this lethal cargo was outward bound from New York, being destined for France.

The only known photographs of the Mont Blanc

Leaving the Bedford Basin in Halifax Harbour, the Imo sailed towards the open sea via the narrows, but due to other traffic and contrary to regulations, sailed on the port (left hand) side of the narrows rather than the starboard (right hand) side. Travelling at seven knots (which although slow, was above the speed limit of five knots), the Imo caused a tug, the Stella Maris to steer closer to the shore to avoid collision.

The Mont-Blanc, meanwhile, had been examined, and had taken on board a pilot. At 7am, the vessel was authorised to make its way through the narrows towards the Bedford Basin. Travelling at four knots, and in the correct lane, she spotted the Imo approaching in her lane.

Collision

The Pilot of the Mont-Blanc gave a single blast on the ship’s whistle to indicate (correctly) that the Mont-Blanc had right of way, which was answered by two from the Imo indicating she was not willing or not able to yield position. Angling towards the right (the near shore) Mont-Blanc again whistled, hoping that the Imo would do likewise and also steer to its right. The Imo again whistled twice. Hearing the series of blasts on the whistles and realising a collision was about to take place many sailors gathered on nearby ships to watch. Both ships had cut their engines but the forward momentum of each ship could not be overcome. A last minute manoeuvre by the Mont-Blanc when she steered to port (left – away from the shore) seemed to have worked (the pilot was desperate to avoid grounding the ship as this was likely to detonate the explosives) and the ships started to pass each other. At this point, the Imo made a fatal mistake and reversed her engines. This caused the Imo’s bows to swing round and she carved into the side of the Mont-Blanc by about nine feet. The impact took place at 8.45am.

Compounding the mistakes already made, the Imo reversed, causing sparks to be created. This ignited vapours released from the damaged cargo and a fire broke out within the Mont-Blanc. Not surprisingly, the crew of the Mont-Blanc rapidly headed for the lifeboats in order to escape from the ship which was likely to explode at any moment.

The tug Stella Maris, under Captain Horatio Brannan, was towing a string of barges at the time of the collision; she responded immediately to the fire, and began dousing down the Mont-Blanc with her hoses.

The Stella Maris.

One of the ships in the harbour was an obsolete cruiser, HMCS Niobe, which was no longer seaworthy and was permanently moored in the dockyard for use as a depot and training ship. After the collision, Niobe's captain sent his steam pinnace with six volunteers - Petty Officer/Stoker Edward Beard and five seamen - under Acting Bosun Albert Mattison to help the stricken vessel.

HMCS Niobe.

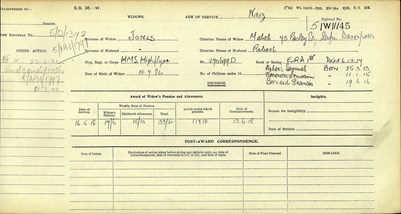

At the same time Niobe's steam pinnace headed for Mont-Blanc, the captain of the HMS Highflyer sent his whaler under Commander Tom Triggs along with six sailors to see if anything could be done.

Approaching the Mont-Blanc, which was now engulfed in flames, Triggs decided to board the tug Stella Maris in order to confer with her captain. After a brief discussion, and leaving the crews of the tug and Niobe's pinnace to deal with the Mont-Blanc, Triggs, in the whaler, was pulling toward the Imo, when the inevitable happened: the Mont-Blanc exploded. The time was about 9.05am, just twenty minutes after the collision.

HMS Highflyer.

The force of the explosion destroyed Niobe's steam pinnacle and killed its crew, while the only person to survive on the Highflyer’s whaler was Able Seaman William Becker.

Above: Engine Room Artificer Robert Jones was one of those from HMS Highflyer to be killed in the explosion. The image is one of the pension records available from the WFA's Pension Records archive.

Mattison, Beard, Triggs and Becker received the Albert Medal. Total fatalities from the crew of HMCS Niobe amounted to fifteen, including Lt-Commander James Murray.

The blast was the world’s largest pre-atomic explosion. Parts of the Mont-Blanc were blown 1,000 feet into the air, some coming down over 3 miles away. The water in the harbour evaporated, and the inrushing sea caused a tsunami 60 feet high which swept into the town of Halifax.

The cloud from the explosion rose over 20,000 feet, and the blast destroyed or damaged every home and factory within a sixteen mile radius – a total of 12,000 buildings. The explosion was felt in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, about 130 miles to the north and even as far away as Cape Breton Island, over 200 miles to the east.

The only photograph of the blast, reportedly taken 15-20 seconds after the explosion.

The aftermath of the explosion. (Library and Archives Canada)

In Halifax, over 1,500 people were killed instantly and probably over 9,000 injured. Amongst those killed were Captain Horatio Brannen and 18 members of the crew aboard Stella Maris (just five survived); the vessel was washed up on the shore. The crew who were on the deck of the Imo were also killed as were many other sailors who had been watching the unfolding drama on board ships in the harbour.

Back on land, the devastation was immense. An eye witness report is available from the one survivor of the 'Patricia' – Canada’s first motorised fire engine. Driver Billy Wells, was opening a fire hydrant at the time of the blast. He recounted the day’s events for the Mail Star, in its edition on 6 October 1967:

…That's when it happened ... The first thing I remember after the explosion was standing quite a distance from the fire engine ... The force of the explosion had blown off all my clothes as well as the muscles from my right arm...

Badly injured, Billy was then nearly drowned as the tsunami came over him. He explained:

...After the wave had receded I didn't see anything of the other firemen so made my way to the old magazine on Campbell Road ... The sight was awful ... with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads off, and some thrown onto the overhead telegraph wires ... I was taken to Camp Hill Hospital and lay on the floor for two days waiting for a bed. The doctors and nurses certainly gave me great service.

A view of the remains of Halifax after the explosion looking toward the Dartmouth side of the harbour. The Imo can be seen aground on the far side of the harbour.

One of the heroes of the day was Vincent Coleman who was a railway dispatcher. When warned of the imminent explosion by sailors who had been sent ashore by a naval officer, Coleman initially left his office to escape but returned to his station when he realised that two trains carrying passengers were on their way to the Richmond station. Going back to his desk at the station's telegraph office, he managed to send a brief warning message along the rail line. Coleman's Morse code message was "Hold up the train. Munitions ship on fire and making for Pier 6... Goodbye boys."

His warning was heeded and trains stopped all along the line. Coleman is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery where a total of eight military personnel who were killed on this day are commemorated.

A building destroyed by the Halifax Explosion.

Aftermath

For some time there was a belief that the explosion was the work of German agents, and a Norwegian sailor on the Imo was arrested as he was thought to be German. The Captain of the Mont-Blanc was charged with manslaughter, but was acquitted at his trial. In 1919 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled the Imo and Mont-Blanc were equally to blame for the tragedy.

There are a number of sites commemorating the explosion, the largest of which is the Halifax Explosion Memorial Bell Tower.

This is the location of an annual civic ceremony every year on the anniversary of the explosion. There are other memorials in the area, and simple monuments mark the mass graves of explosion victims at the Fairview Lawn Cemetery and the Bayers Road Cemetery.

The Imo was repaired and, renamed Guvernøren (“The Governor”) in 1918, returned to sea. She served as a whale oil tanker until November 1921, when she ran onto rocks at Cow Bay off the Falkland Islands.

Article by David Tattersfield