The Youngest Colonel?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Youngest Colonel?

When we think of ‘young soldiers’ in the Great War, we often think in terms of those who were killed aged 17 or younger. There are many claims and counterclaims about the ages of some of these boys who were killed. But there is also another factor to look at, and that is of those officers who achieved high rank in their early to mid 20’s. One example of this is Brigadier General Roland Bradford who was killed aged 25.

However there are other examples of ‘young’ officers. In Cabaret Rouge Cemetery is the headstone of Lt Col Eric Bowden (who died aged 24) which states he was one of the youngest Colonels in the British Army.

This is true, but he was not the youngest.

The youngest Lt-Col to be killed in the war would appear to be John Hardyman who was aged 23 when he was killed on 24 August 1918. Hardyman enlisted in the 4th Somersets at Bath in August 1914 before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps, a move which did not work out, as he was to return (commissioned) to the .

Photograph of Hardyman presumably shortly after enlisting as a private. (from Opusculum)

The 8th Somerset's war diary (WO 95/2158/3) records that 2nd Lieut. J. H. M. Hardyman was one of eleven officers that joined the battalion on the 28th July 1916, while the battalion was still restructuring after the opening day of the Somme offensive. There followed what can only be described as a 'meteoric' rise in rank which culminated in him commanding the battalion little more than two years later, as seen in the following entry:

6.6.18. Temp.Major (a/Lt. Col.) J.H.M. HARDYMAN, M.C. took over Command of the Battalion.

In Everard Wyrall's, The History of the Somerset Light Infantry (Prince Albert’s), 1914-1919 there is the following detail of an action some weeks later:

24th August. On the morning of the 24th the New Zealanders attacked and captured Grevillers. The 63rd Brigade, being ordered to co-operate in this attack, moved off to form a defensive flank on the left and capture Biefvillers.

The advance began at about 5 a.m. and consisted of section rushes, the enemy’s machine-gun fire being very heavy. Eventually, with the assistance of tanks and the New Zealanders, Biefvillers was taken at about 6 a.m. But the left flank of the Somersets was in the air and the village under an extremely heavy bombardment. It was therefore decided to evacuate Biefvillers and a position was taken up on the high ground immediately west of the village.

It was during a personal reconnaissance that Lieut.-Colonel J. H. M. Hardyman, the C.O., was killed by a shell. With his Battle Headquarters he had previously moved up to this position in a tank. The Divisional Commander sent the following message to the 8th Somersets:–

“The Divisional Commander wishes you to congratulate LOGE (8th Somersets) on the capture of Biefvillers which was of the utmost importance to the present operations. He deeply regrets the death of Lieut.-Colonel Hardyman in the moment of victory. His splendid leadership and magnificent gallantry will never be forgotten.”

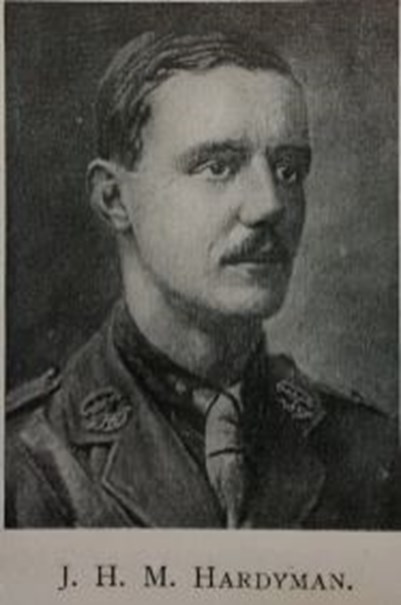

His two years in France clearly seem to have aged him, the image below seems to be that of someone much older than 23

De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour gives a potted history of his service.

HARDYMAN, JOHN HAY MAITLAND, D.S.O., M.C., F.Z.S. (Scotland), Lieut.-Col. 8th (Service) Battn. Prince Albert’s (The Somerset Light Infantry), eldest s. of George Hardyman, of Perrymead Court, Bath, M.B., M.O.H.,m Surg., F.R.C.S.Eng., F.R.M.S.Edin., by his wife Eglantine Henrietta Keith, dau. Of the late Lieut.-General John Maitland, R.A., of Freugh and Balgreggan, co. Wigton, also of Perrymean [sic] House [i.e. Perrymead House], Bath: b. Bath, 28 Sept. 1894; educ. Hamilton House School, Bath; Fettes College, Edinburgh, where he was an Open Scholar, and Edinburgh University; was assistant to the Professor of Botany at Edinburgh University, in Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh; became F.Z.S. (Scotland) while a student, and was a member of the Students’ Representative Council; joined the 4th Battn. The Somerset Light Infantry (T.F.) 19 Aug. 1914; was attached as pilot pupil to the Royal Flying Corps the following Dec.; after two aerial accidents returned to the 8th Somerset Light Infantry; gazetted 2nd Lieut. 23 Feb. 1915; promoted Lieut. 19 Nov. 1916, Capt. 12 April, 1917, Major, 13 April, 1917, and Lieut.-Col. 6 June, 1918; served with the Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders from July, 1916; was wounded at Beaucourt 18 Nov. following; on recovery returned to his unit; was wounded in the Battle of Arras 10 April, 1917, and slightly wounded at the Battle of the Scarp [i.e. Scarpe] on the 23rd of that month, and was killed in action at Bienvillers [i.e. Biefvillers-les-Bapaume] 24 Aug. 1918.

Buried in the British Military Cemetery, Bienvillers. He was mentioned in Despatches (London Gazette, 18 Dec. 1917) by F.M. Sir Douglas Haig, for gallant and distinguished service in the field, and was awarded the Military Cross: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion in several dangerous reconnaissances, in one of which he was wounded. He displayed great bravery in organising the clearance of wounded from a medical aid-post near an ammunition dump which had been set on fire by shells.”

He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order (London Gazette, 27 Aug. 1918): For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. After the enemy had penetrated the line in three places, he went forward through a heavy barrage to the forward posts, rallied the garrison and encouraged them by his coolness and absolute disregard of personal danger to successfully repel repeated enemy attacks extending over two days and three nights. Thanks to his gallant leadership and endurance, the position, which was of great tactical importance, was maintained'. Lieut-Col Hardyman had the distinction of being the youngest of his rank in the British Army.

Who knows what Hardyman would have achieved had he lived. Clearly he was highly regarded and his achievement is probably at least equal to that of the far more well known Brigadier General Bradford.

Other officers

Besides Lt Col Hardyman, there are numerous other ‘young’ Lieutenant Colonels worthy of research, as well as men of other rank. Perhaps the case of two brothers can be used to show how one family had two sons reach high rank, but to lose them in action during the war.

Owen and Philip Howell-Price were killed at the ages of 26 and 23 (a 3rd brother – Richmond - also fell, aged 20). Philip was a Major in the 1st Battalion AIF, and Owen a Lieutenant-Colonel, commanding the 3rd Battalion AIF. It is unlikely that any other family lost sons of such a young age who had achieved these ranks.

Dr Meleah Hampton who is the Historian at the Military History Section, AWM has written:

Owen Glendower Howell-Price was born on 23 February 1890 in Kiama, New South Wales. He had served with the citizen forces, and so on the outbreak of the First World War he applied for and secured a commission into the 3rd Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force.

Howell-Price was with his battalion for the Gallipoli landings, and during the attack on Lone Pine in August 1915 he displayed “conspicuous gallantry” and the “greatest bravery” in leading an attack against the Turkish trenches. For his actions at Lone Pine Owen Howell-Price was awarded the Military Cross.

Known as “the gentlest of men and conscientious to a fault”, Howell-Price was made permanent commander of the 3rd Battalion in March 1916, making him one of Australia’s youngest senior officers at the time.

It was at Pozières that Howell-Price’s ability to command became most apparent. The 3rd Battalion was integral to the successful capture of the village on 23 July 1916, and at all times its commander showed a marked devotion to duty and to his men, and on at least one occasion remained in the front line despite being wounded.

However, his hands-on approach to battalion command would become his downfall. In early November 1916 the 3rd Battalion was taking part in an operation near the French village of Flers. While supervising the emplacement of machine-guns to cover the advance, Owen Howell-Price was shot in the head. He died of his wounds the following evening, on 4 November 1916. He is buried at Heilly Station Cemetery.

Owen Howell-Price was twice Mentioned in Despatches for his work on the Western Front, and was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order. In him the first Australian Imperial Force lost one of its most promising young commanding officers, a diligent and able man who demonstrated great ability in the technologically driven battlefields of the Great War.

A group portrait of officers of the 3rd Battalion in front of a large Union Jack flag bearing the words 'Loyal Australia' across the middle. Identified is Lieutenant Owen Glendower Howell-Price MC (front row, fourth from left). Image courtesy of Kiama Library via Flickr.

Dr Meleah Hampton continues:

Philip Lewellyn Howell-Price was born on 11 September 1894 at Mount Wilson. He, like his brother, had experience in the citizen forces, and on enlistment received the commission of second lieutenant. He would continue to gain regular promotion throughout his military career.

Philip Howell-Price served with the 1st Battalion, and was with them when they landed on Gallipoli in April 1915. There he served with distinction and was twice commended for acts of conspicuous gallantry and valuable services during the early months on the peninsula.

Philip was Mentioned in Despatches for his actions during the battle of Lone Pine in August 1915. Towards the end of this operation he was wounded in the back by a bomb. It took him nearly three months to recover, but he returned to Anzac Cove, staying until the evacuation.

Philip Howell-Price regularly demonstrated a capacity for military leadership and bravery that would see him decorated several more times. In 1916, shortly after arriving in France, he successfully led a raiding party of four officers and 60 men in one of his battalion’s first operations, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

He received the Military Cross later in 1916 for his leadership of a company of men in an operation near Flers. The following year he was shot through the thigh, but remained on duty despite his wound. His service was regularly noted as a “fine example of bravery, devotion to duty, and self-sacrifice”, and he was considered “an inspiration to his men”.

In October 1917 Philip Howell-Price was in the trenches with his battalion when he gave the order to move. At this point an artillery barrage began and a shell burst near the place he was last seen. His body was never recovered. He is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial.

Did COs become younger during the war?

The question arises about the average age of battalion commanders. Peter Hodgkinson has commented:

The average age of Lieutenant-Colonels in France and Flanders dropped 12 years 11 months between August 1914 and 29 September 1918, from 47 years 10 months to 34 years 11 months. This drop should not be attributed solely to design, as it was clearly strongly connected to attrition resulting from death, wounding, invalidity or promotion/removal of older COs. Any design element appears in the deliberate replacement of older COs for fitness reasons. Succession by younger men was, however, inevitable.

At least 25 Lieutenant Colonels were younger than Eric Bowden. Whilst it might be thought that the fact that COs became progressively younger is evidence of an emerging meritocracy of youth, the reality that older than average COs were still appointed in 1918 supports the Official Historian’s view that age is purely biological, and not a bar to the appointment of a competent commander.

The youngest known CO on 29 September 1918 was Lieutenant-Colonel A.L.W. Newth of the 16th Cheshire, who was 21 when appointed on 30 April 1918, and he was likely the youngest of the war. Arthur Leslie Walter Newth, was born in 1897 and commanded 1/6th Cheshire from 30 April 1918 to the Armistice. He served as a Brigadier-General in the Second World War.

Further Reading

The Three Howell-Price brothers

British Infantry Battalion Commanders in the First World War by Peter Hodgkinson

You Tube: Battalion Commanders in WW1

Article by David Tattersfield