To Cross the Rubicon You Need… Life-Jackets! The 46th (North Midland ) Division Crossing of the St Quentin Canal: A Supply Perspective

- Home

- World War I Articles

- To Cross the Rubicon You Need… Life-Jackets! The 46th (North Midland ) Division Crossing of the St Quentin Canal: A Supply Perspective

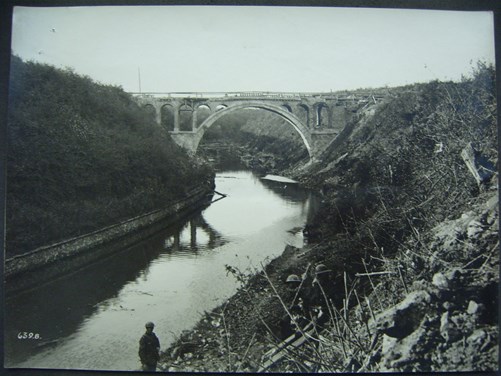

One of the most remarkable ‘tactical incidents’ (as the official battle nomenclature describes it) of the Battle of St. Quentin Canal was the ‘Passage at Bellenglise’ and in particular the capture of the vital Riqueval Bridge by 137th Brigade (46th North Midland Division) on the morning of 29 September, 1918.

This action gave rise to one of the most iconic images of the war: the sight of 137th Brigade troops posing victoriously on the steep bank of the St Quentin Canal after a successful crossing wearing an unusual addition to their standard battle dress - life-jackets.

In the event the life-jackets (and rafts, floating bridges, ‘mud mats’, collapsible boats, ropes and sundry other means of crossing) were not really needed thanks to the heroic actions of Sapper Fred Openshaw of 466th Field Company (Royal Engineers) who, with ‘A’ Company, 1/6th North Staffs Battalion, captured the bridge before it could be demolished by its German defenders.

Since life-jackets are not ‘standard stores’ the question arises: how did 137th Brigade acquire 3,000 life-jackets at short notice? RE Priestley’s story of the 46th Division, ‘Breaking the Hindenburg Line’, attributes this to ‘some genius’ who simply telegraphed the authorities at Boulogne who gathered 3,000 life-jackets from leave boats and sent them up the line. The question of how those life-jackets were ‘sent up’ is ignored thereby obscuring the contribution of one of the most potent weapons at the BEF’s disposal in 1918: its outstanding administrative and logistical system.

Without a detailed study of a very large number of relevant primary documents from brigade, division, corps, army and GHQ it is impossible to identify with absolute accuracy the precise administrative and logistical channels used. Despite this the BEF ‘system’ was by 1918 extraordinarily well-organised and used what we would call today ‘SOP’s’ or Standard Operating Procedures so it is possible to reconstruct their journey.

The initial request from brigade would have gone through the division’s AA & QMG and thence to IX Corps DA&QMG while the relevant Fourth Army and GHQ staffs were kept ‘in the loop’. That request would then move through the Quartermaster-General’s (QMG) office at GHQ and thence to the Commandant of Boulogne Base who allocated as many life-jackets as possible from stock with the balance coming from the boats themselves. Although cork life-jackets are relatively light they are bulky so the QMG’s task was to provide rail transport from port to railhead while IX Corps Senior Mechanical Transport Officer (SMTO) specifically allocated lorries from his pool of lorries, if necessary in conjunction with Fourth Army Deputy-Director, Supplies and Transport (D-DS&T) and possibly GHQ Motor Transport Reserve. From the railhead 3-ton lorries were used to transfer the life-jackets to the Divisional Refilling Point whereupon they were transferred to Horse Transport and distribution through brigade down to battalion level.

What is most remarkable about this is the speed at which it was done. The first divisional order for the attack was issued on 25 September. By the evening of 28 September they had been delivered, tested and were ready for issue. Even assuming commanders were already preparing for an assault, all the complex administrative and logistical details were worked out, organised and executed within 3-4 days! This represents an incredible achievement that would have taken at best 10 days or more in 1917 and is testament to the professionalism, flexibility, organisation and responsiveness of both the BEF’s supply system and the much-maligned ‘Bloody Red Tabs’ that made it happen.

A ceremony marking the taking of the Riqueval Bridge and re-dedication of a plaque marking their achievement is taking place on Saturday 29 September, with further commemorations on Sunday 30 September.