We Rest Below the Waves

- Home

- World War I Articles

- We Rest Below the Waves

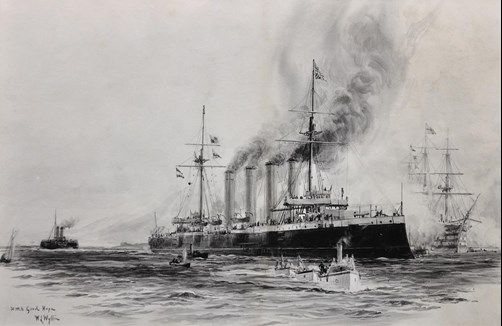

Stoker 1st Class Herbert Allcorn had already served five years in the Royal Navy and was on Reserve when he was called back to duty in 13 July 1914 as there was a possibility of England going to war and drafted to the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope. His ship carried a complement of 900 crew and was powered by 43 coal fired Belleville boilers capable of producing a maximum of 23 knots. Her armament of two 9.2 inch guns in single turrets, sixteen 6inch guns in casements along the hull, twelve 12 pounder guns, three 3 pounder guns and two 18 inch submerged torpedo tubes. HMS Good Hope was a formidable old fighting machine and had only recently been taken out of retirement. The crew at the time were mostly reservists like Stoker Allcorn. When war was declared on 4 August, Good Hope left Plymouth on the 6th to do battle with Admiral Graf von Spee‘s German East Asia Squadron which was successfully disrupting trade with Australia, New Zealand and India. This was causing great problems for the British Admiralty. The British force sent to engage the enemy fleet consisted of the armoured cruisers, Good Hope and Monmouth, the light cruiser, Glasgow and the armed merchant cruiser Otranto and the worn out old pre dreadnought Canopus .The fleet was under the command of Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock whose flag was aboard Good Hope.

'HMS Good Hope' by William Lionel Wyllie

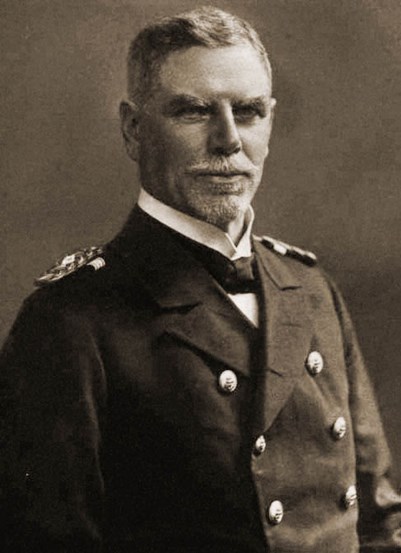

Graf Maximilian von Spee’s squadron consisted of two light cruisers, Leipzig and Dresden and two modern armoured cruisers, the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau which were better armed, better armoured and better equipped than anything the British fleet had. The German crews already had an advantage over the opposing force looking for them. They were expert in naval gunnery and trained regularly whereas the British were predominantly reservist crews who hadn’t had much time to practice or even get to know their ship.

Maximilian von Spee

At 1620 on 1 November, the two fleets caught their first glimpses of each other off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. Rear Admiral Cradock frantically radioed Canopus to catch up but it was a hopeless task as she was approximately 250 miles behind and was to take no part in the looming battle. Each squadron commander attempted to size up the situation and manoeuvre for the best position to engage the enemy. The British tried to open the engagement early with the sun behind them in the hope of a swift victory. The Germans would have had to look into the sun so Spee avoided battle by manoeuvring his faster vessels out of Cradock’s range. However, as the day wore on; the sun began to set and presented the British fleet in sharp silhouette against the horizon. The German ships were by now, almost invisible in the gathering gloom and finally from a tactical advantage, commenced firing at about 1900.

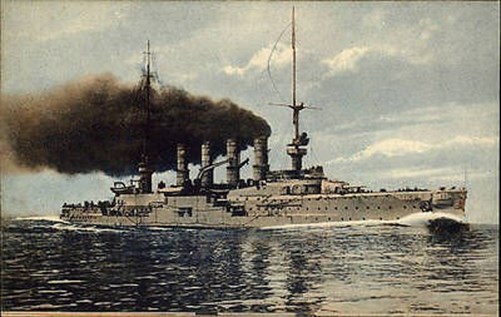

The Scharnhorst scored a direct hit on Good Hope with her third salvo destroying the forward 9.2 inch main turret. Three minutes later, Monmouth was set on fire by Gneisenau’s accurate gunnery. The British fired every available gun but with little serious effect on the Germans except for a couple of damaging hits on Gneisenau by Monmouth. Superior German gunnery and battle tactics began to shape the final outcome. By 1935 von Spee estimated that Good Hope had been hit thirty times. She was on fire in several places but still fighting. She even tried to close with Scharnhorst so as to launch a torpedo attack. The German ship kept its distance and continued shooting. As the visibility decreased, the Germans had the advantage of using the fires on the British ships as aiming points whereas the British gunners could only aim at the enemy gun flashes. Leipzig and Glasgow engaged each other whilst Dresden shelled Otrango which pulled out of the line and retired. Dresden then turned its attention to Glasgow. Monmouth was at this point, on fire and listing to port and. signalled Glasgow to make its escape rather than attempt a tow. Glasgow had been hit five times and retired from the line on orders to warn Canopus to stay clear of the battle. The newly arrived Nurnberg finished off Monmouth at point blank range. There were no survivors. At 1957 a brilliant flash of a magazine explosion came from where Good Hope had last been seen. Nothing was ever found of her and Admiral Cradock, together with the entire ship's complement of 900 men, perished. Dresden and Leipzig were dispatched to hunt down Glasgow and Otrango. The British lost two cruisers and 1654 crew killed. No survivors were found. The Germans only suffered four hits and three crew wounded on the Gneisenau and two hits on Scharnhorst. Spee took the remainder his fleet to Valparaiso to re stock coal and provisions. It was a great victory for Germany but the euphoria wasn’t to last long.

SMS Gneisenau

The scale of the loss and the terrible humiliation of the first defeat of British sea power for over a century stung the British Admiralty in London into action. A huge naval force was assembled under Admiral Sir Fredrick Doveton Sturdee and his fleet eventually came to grips with Graf von Spee’s force near the Falkland Islands on December 8. In the ensuring battle, the Scharnhorst, Leipzig, Gneisenau and Nurnberg were sunk. Dresden managed to escape. No British ships in the engagement were lost and British honour was restored. In a strange turn of fate, it was the Glasgow that finally found the Dresden anchored in neutral Chilean waters at Mas a Tierra. In a blatant violation of Chilean neutrality, Glasgow opened fire on Dresden. After 5 minutes Dresden surrendered but during surrender negotiations, the Germans scuttled the ship denying the British the prestige of capturing their ship and its possible use.

Stoker 1st Class Herbert Allcorn rests below the waves and has no known grave, but he and his ship mates lost on that fateful November day are not forgotten. The Portsmouth Naval Memorial commemorates those Royal Navy ranks and ratings that have no known grave other than the sea. The names of 9,666 from the Great War and 14,922 from World War Two are arranged according to the year of death. In addition there are 75 names of those from Newfoundland who died whilst on active service with the Royal Navy.

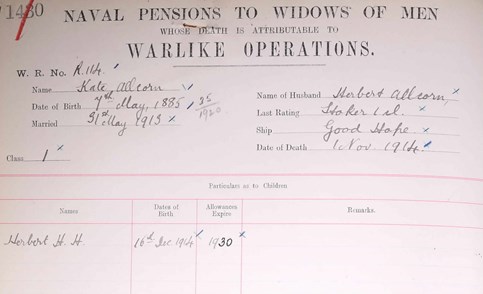

In the case of Stoker Allcorn, his medals were sent to his widow in Ringmer who was pregnant at the time of her husband’s death. At the christening, a son was named Herbert Henry Hope Allcorn on 7 February 1915 after his father and his ship.

Above - a section of the Pension Record for Herbert Allcorn's widow's Pension Award. Details of these Naval Ledgers can be found HERE > WFA Naval Ledgers

References.

Kind permission. Bridger. Geoff.

www.ringmer.info/rhsg/herbertallcorn.htm

www.answers.com/topic/hms-goodhope

www.answers.com/topic/battle-of-coronel