Animals in the Great War

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Animals in the Great War

Pages: 117

Illustrations: 32

ISBN: 9781473838048

Published by Pen & Sword: 17th June 2019

There is room for a book on animals in the First World War but this is probably not it - or at least not this edition. With a firmer editorial hand and support on the military history of the First World War much more could have been achieved.

Animals in the Great War has is strengths and weaknesses.

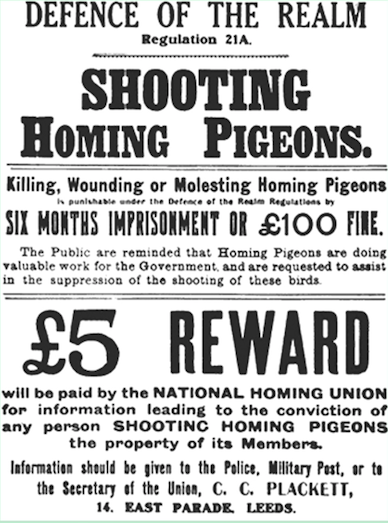

The strengths lie in the considerable efforts the authors have taken to squirrel out many intriguing facts, details and anecdotes on horses, elephants, camels, cats, dogs and pigeons, as well as goats, a kangaroo, baboon and crow ... and their roles during the First World War.

It is a distraction and irrelevance however to be expected at times to read through stories concerning these animals long before the First World War or potted biographies about the cavalrymen that have little or nothing to do with the horses they were riding - the easiest thing the reader can do is to skip these pages. The authors and editor should have removed them from an early manuscript. Mules are mistakenly thrown in with horses - they deserve a chapter of their own.

There are a number of weaknesses: there is an expectation when reading a book titled ‘Animals in the Great War’ that this is what it will be about from cover to cover - even if it means cutting out 20 or 30 pages of text.

The history is flawed. A book that talks of generals as 'cavalry loving relics' who had no understanding of innovation such as aeroplanes smacks of the kind of nonsense written about the British Army and its generals in the 1960s - we have moved far beyond this view in our evidence-based understanding of the decision making processes.

The authors fall for every cliché and myth when it comes to the cavalry during the First World War. By deleting the ideas expressed on military history this volume would be greatly improved.

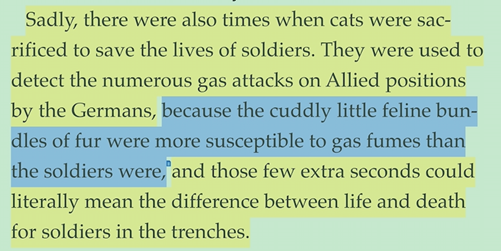

I rather feel the authors are still looking for their voice - it is easy at times to think that ‘Animals in the Great War’ is aimed at children not adults - moments such as this come to mind:

Knowing who you are writing for matters. Whilst there is charm in a book that is dedicated to the memory of the family pets: dogs, cats and guinea-pigs, 21st century sentimentality over working animals and their role 110 years ago has no place in a history book. In first decades of the the 20th century working animals were just that - on the roads, in fields, as beasts of burden and for food, in mines and at war. Chickens were raised for their eggs and meat - not as pets. Indeed some reading this may recall stories of their parents or grandparents keeping rabbits during the Second World War to supplement the pot a time of rationing.

It is questionable that elephants 'willing worked carrying out parade, drill and marching, keeping ranks, and even keeping themselves clean’. This shows a poor understanding of what it takes to train an elephant to be compliant - taking a young elephant most unwillingly from its mother and using force and starvation to train it. Exploitation of animals is also a history of mankind.

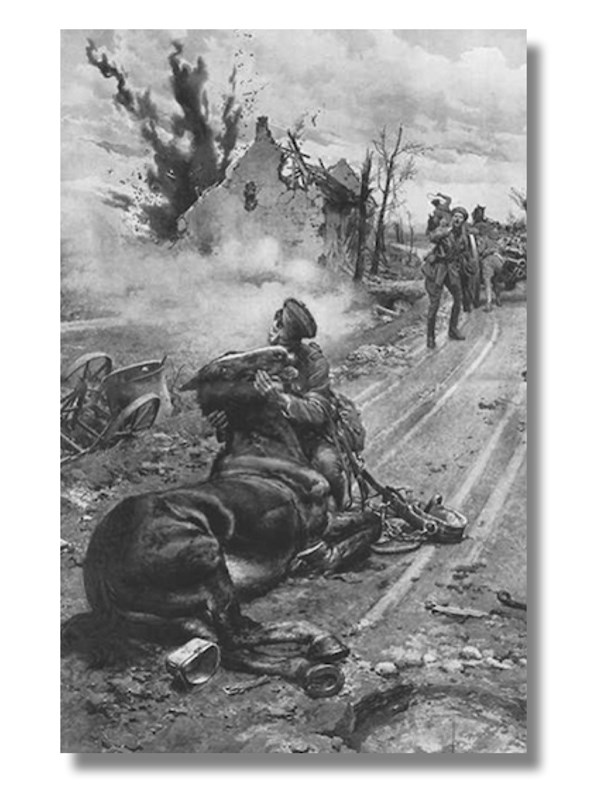

Not one single photograph is adequately captioned with its original title or source; this is a shame, not least because an artist such as Fortunino Matania deserve credit for his extraordinary ability to reproduce with a painting or drawing something like 'Goodbye Old Man' - fully captioned below.

Cod psychology on the benefits of pets to men at war, whether on a ship, in the trenches or on an airfield is just that unless qualified by evidence - it is wrong to suggest that men were ‘devoid of love and affection’ away from their families - comradeship as any veteran would tell you is a key part in their commitment to a unit, even why so many craved a return to 'their lads'.

In conclusion, there are strengths to ‘Animals in the Great War’ with many unique photographs and new stories concerning animals at war in the early part of the 20th century and it is a valuable assembly of facts about the numbers and variety of animals used during the First World War (though with no referencing at all these are impossible to verify).

The weaknesses already mentioned could largely have been addressed with the input of a military historian and a good editor.

I wonder what Michael Morpurgo would have done with the anthropomorphic story of a camel, elephant or dog in the First World War rather than a horse?

Further Links:

From Mentioned in Dispatches (podcast) : Lucinda Moore discusses her book Animals in the Great War

From the Imperial War Museum : 12 Ways Animals have helped the war effort