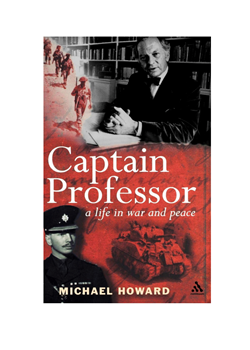

'Captain Professor - a life in war and peace' by Michael Howard

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- 'Captain Professor - a life in war and peace' by Michael Howard

You will rarely find an autobiography that is this detailed and self-effacing. We learn 2/3rds into ‘Captain Professor - a life in war and peace’ that he kept a diary while teaching at Yale, you rather suspect that he kept a diary through-out his life.

Howard remarks with the demise of his mother, that between them, father and mother, lived through the transformative century 1877 to 1977, yet it is palpable on reading ‘Captain Professor’ that he too lived through, experienced first hand, a remarkable period of transformation in British life 1922-2019.

Howard was born into a wealthy, ‘upper-middle class’ Edwardian family that lived in the ‘upstairs-downstairs’ life of South Kensington with seven servants all of whom had a specific role, and three of whom we still retained by his mother many decades later. There was significant wealth in Britain between the wars. Owning a pharmaceutical manufacturing business saw the Howards in the pink.

Michael Howard describes in detail their lifestyle, and names everyone with the forensic exactitude of an historian. You have to believe it. From life at home, to that of a prep-school and public-school boy, the detail is Pre-Raphaelite. This is the historian who is a piece of history himself. Anyone who experienced boarding prep-school and public school through to the 1970s will relate to his experiences of 35 years earlier. There are insights here of teaching practices, some progressive and applicable to the 21st century ‘flipped classroom’ where students are encouraged to undertake study away from the class ahead of discussions and help with a topic on their return. Abinger sounds enlightened. Those who got behind were helped, those who raced ahead were given greater challenges.

You may find yourself following up the books that he read that inspired his interests. Peacemaking 1919 by Harold Nicholson is the first of many references you may find yourself chasing.

Howard made it to Oxford to study history (age 17), but his studies had to be aborted after a couple of years so that he could serve during the Second World War. Age 20, he found himself in Italy.

His experiences are bathetic in the way he tells them. There is resonance here with many a combatant’s experience. To pass a body, to witness a colleague or friend killed becomes part of the ‘job’. Howard describes his first body in gruesome detail. This is a reality and honesty of war that is glossed over with the repeated reports to the family that he was ‘shot through the head’ and felt no pain … too often the truth buried. Not so with Howard, not his experience, his actions and especially his feelings when they were to him significantly less than heroic. He even makes the point that the most heroic deeds are not those witnessed by superiors that could result in recognition, like his MC.

Throughout, Howard is self-effacing and honest, both with his terror of feeling ‘fear’ and decisions and actions that he would contemplate for decades after. There are subtle changes recognised between First and Second World War behaviours. As a junior officer his role is to lead and guide his men, not necessarily to be the one in front to be killed first, something his Sergeant Major queries. Some lessons had been learnt.

The idea of a military historian having military experience is sometimes derided, but in this instance, the ever present chance of life or death, or a ‘poor death’ is shown to colour his opinion profoundly.

There are no ‘boring bits’. Howard apologies in advance, by now in his 60th year, and teaching at Yale, that talking ‘teaching history’ may be something of a routine bore, but it is never said. He comes over as someone who was able to follow his enthusiasm, which he chased with conviction and determination. He admits that saying “Yes” ' to all manner of opportunities found him advising the government (and Margaret Thatcher), running a college and even being the one thing he despised the ‘God’ Professor who did a routine lecture a term but was otherwise never seen. His sexuality is not challenged. He navigates his homosexuality sensitively and under the radar.

The insights you gain from ‘Captain Professor’ are many, and much of it applies to 2020 as it does to the 1960s, 70s, 80s or 90s. You get to know the man, who can be summed up as a natural ‘educator’. He was fortuitous in his decisions and passions, firm when challenged and always curious enough to take up new opportunities every seven or eight years.

On many levels this is fascinating read: his life born into upper-middle class wealth in the 1920s and serving through the Second World War in Italy, a perspective on higher education and the establishment of Military History as a distinct branch of academic study in its own right, and the perspective of an honest pair of eyes on the extraordinary transformation in British society from the 1950s through to the present day.

Michael Howard’s ‘A First World War. A Very Short Introduction’ is an easy, and honest introduction to the war 1914-1918. You should find yourself reaching for The Franco-Prussian War and War in European History … as starters.

Review by Jonathan Vernon, Digital Editor, The Western Front Association.