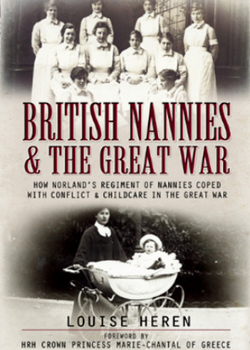

How Norland’s Regiment of Nannies coped with conflict and childcare in the Great War.

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- How Norland’s Regiment of Nannies coped with conflict and childcare in the Great War.

By Louise Heren, published by Pen & Sword, 2016.

The Forewords are by HRH Crown Princess Marie-Chantel of Greece, and Liz Hunt, the present Principal of Norland College.

We have read about Tommies in the Great War as well as experiencing their stories on stage and screen, plus the officers, junior officers and even animals, but Nannies? This book is about the Norland College Nannies who trained at this prestigious establishment. The research is meticulous and stories of so many Norland Nannies are told through their letters home. The beautifully presented photographic plates transport the reader back in time and helps to visualise Mrs Ward and other Norlanders.

The Prologue features Nurse Kate Fox who finished her course in 1895 and became a nanny to the Greek Royal Family in September 1903. By 1913 many graduates of Norland College were also working in Royal households, but Kate’s employment was terminated and the reasons behind the dismissal gradually became known from correspondence she had with her previous charges. Prologues are often ‘skipped’ but this one is as interesting as any chapter that follows. Kate Fox, an outspoken Norlander, is a constant within these beautifully written pages, as is Mrs Emily Ward, founder of the Norland College in 1892. Each chapter tells of the experience of different Norland Nannies, many working in Germany, who had to leave the children they loved and were caring for, to return to Britain when war broke out on the 4th August 1914.

‘Patience, courage, hope and humility were attributes that British society of the time expected of its womenfolk, but they were especially applicable to the Edwardian Norland Nurse.’ It was a class-ridden society and the Norlanders came somewhere between the lower and upper classes. Until the outbreak of the Great War it was unusual to see a middle-class young lady in uniform and in 1900 nannies wore their own clothes. However, Norlanders were the exception and did wear a uniform. By the turn of the century the eight-year-old Norland Institute was the flagship of such training establishments that followed across the country, although Norland’s nurses were considered to be ‘the best’ in their field. This may have had adverse results as Norlanders were expected to work longer hours, expected to work for eleven consecutive months, usually with no designated days off, before they could earn a holiday. They also had to live by a strict set of rules. Many Norlanders had previously worked in other areas to earn enough to pay for their training at Norland College. Sadly some nurses didn’t complete their probationary year because of a lack of practical work with children; they only spent a short time on a children’s hospital ward. Norland’s role changed, however, when babies and children were introduced into the care of its nurseries affording different training for less well off young ladies and ideal for families considering employing a Norland Nanny.

The suffrage movement was growing and Norland Nannies wrote freely on emancipation and by 1910 Royal employers were visiting the institute, especially those from Germany and Greece. However, when the government’s National Insurance Act became law in 1911 the nannies, earning less than £160 per annum, found that they had to insure themselves; this was to be the beginning of the National Health Service.

When war was declared, of the five hundred qualified nurses working in mainland Europe, fifty-four were Norlanders. As Louise Heren states: ‘they lived an Edwardian, ‘Mary Poppins’ existence bound by the confines of their nurseries and the proper upbringing of their charges’. When Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914 the Norland nurses working overseas were thrown into turmoil and their positions became untenable. Heren tells of the struggles of these young women in their attempts to return home where they witnessed violence and fear for their own lives, and of those who remained in France. Norland Nurses were not all working in Britain though and many were scattered Further Afield - South Africa, Canada, Greece, for example.

On their return to their families in England, some found it difficult to settle back into rural life with such animosity towards the Germans with whom they had been living as part of their family. The ladies from Norland College, who had taken up prestigious positions overseas, suffered in the same way as their employers and ‘did their bit’ to help the cause. By Christmas 1914 some nannies had been dismissed due to financial constraints and some of those who were training at Norland College took up ‘men’s work’ hoping to return to Norland after the war was over.

Those with positions in Britain would join in with charitable events organised by their employers. They were not allowed to treat the returning injured; this role was for the trained military nurses. Although keen to help, most Norlanders continued with their day-to-day employment. As the Belgian refugees arrived, the Norlanders helped with clothing depots but some wanted to do more than this, but there were few opportunities as nursing outside the military was still barred, but some did find a way; they signed up for the Voluntary Aid Detachment and the Red Cross.

Initially these young ladies may not have suffered personal loss as the war progressed and when one of their former charges became distinguished for bravery, they shared their pride in Norland’s Quarterly Magazine. Although their joy turned to sadness when any of their charges were killed in action.

The chapter entitled War in the Nursery illuminates the escalating difficulties the Norlanders were experiencing; even buying their uniform became problematic. And in Missions and Mothercraft we learn that Mrs Ward also had to change some of her rules, especially that of expecting married Norlanders to leave her employment, as had been the case prior to 1915. As the war progressed more young women took up work in factories, and the Norlanders saw these young ladies being able to afford new clothes and make visits to the Music Halls, but they couldn’t and by 1916 morale was dwindling. Between Christmas 1917 and Autumn 1918 there were no further editions of the Norland Quarterly as paper had become expensive. November 1918’s Quarterly, which marked the Armistice, was a lean affair.

Miss Isabel Sharman is another constant throughout the monograph; she had been the College’s Principal for twenty-five years. Miss Sharman died in 1917 and ‘the Isabel Sharman Memorial Fund’ was created to give the less well-off a chance to train at Norland.

By November 1918 over 200 nurses had taken up ‘war work’ and the college had an average of 700 nurses on their books during every year of the war, and in the early months of 1919 the demand for Norland Nurses was still high and there were forty to fifty daily requests for nurses, although these were mostly for younger Norlanders.

Whilst spirits were rising so too was the cost of living and working Norlanders embraced what lay ahead of them, but one Nurse was working in Finland and her life of luxury descended into hardship, but she resolved to remain with the family ‘whatever the future held’. Around seventy or eighty nannies had left Norland during the war years to get married, and after the Armistice new applications were welcomed.

On the 25th September 1919 the Norland Nannies enjoyed their first ever reunion attended by Madame Montessori, Europe’s leading educationalist.

Europe’s nobility was decimated by the war, but Mrs Ward’s Norland proved that it could ‘move with the times’ and embarked on finding new clients in the USA and Middle East.

The Epilogue returns to Kate Fox ‘a legend among Norlanders, the last of the cohort that set Norland on the international stage’.

Initially, I wasn’t sure I was going to enjoy this book, but I did. It was absorbing and, at times, gripping. I really wanted to know what happened to each of the nannies, or Norland Nurses, as they were known, and the research has brought the fascinating lives of these spirited young women into a tangible existence once more .

A fitting work of remembrance and commemoration of a cohort that has been previously overlooked.

Dr Karen Ette

FOOTNOTES

1) Louise Heren, British Nannies & The Great War: How Norland’s Regiment of Nannies Coped with Conflict and Childcare in the Great War (Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2016), p. 78.

2) Heren, p. 45.

3) Heren, p. 88.

4) Heren, p. 156.

5) Heren, pp. 149-150.

6) Heren, pp. 161-62.

7) Heren, p. 166.

8) Heren, p.197.