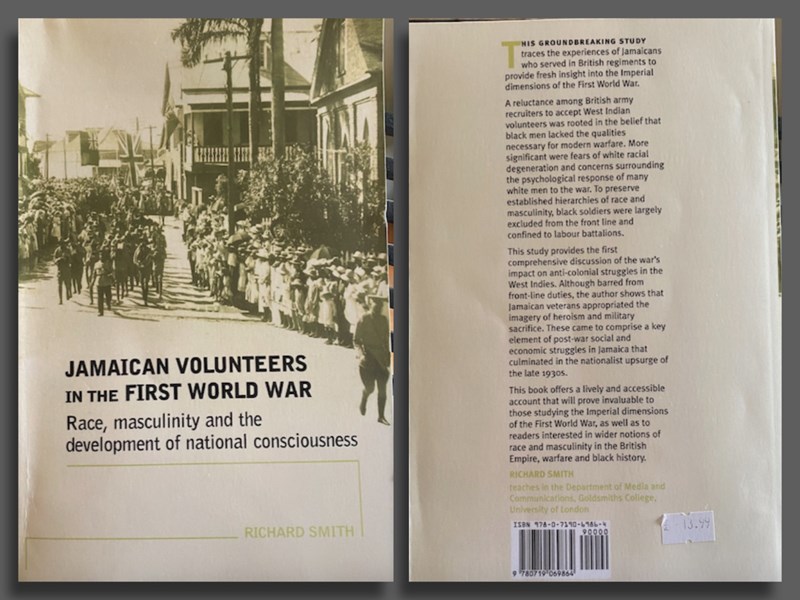

Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War by Richard Smith

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War by Richard Smith

Subtitle: Race, Masculinity and the Development of National Consciousness

Publisher: Manchester University Press (2004)

ISBN: 9780719069857

Richard Smith

Like African-Americans from the US, Jamaicans had a fight on their hands when they returned to Jamaica after the Great War of 1914-1918. Their political and economic struggles, already apparent before the war, came to the forefront having been ignited by their ambitions and fueled by their expectations. The well known racist views and behaviours of white American were little different amongst the white British. For example, ‘Neither women nor coloured troops could be used in Field Ambulance or convoys to replace medical personnel’ ( p.79) - let alone to serve in front line positions.

In relation to the British Empire it was just the same for Indian Nationalism where 'declarations of loyalty and support for recruitment did not lead to self-government.’ (p.4) All told, it took two world wars to have a true impact on colonialism and Empire.

Jamaican Volunteers in the First World War tells the story from the point of view of Jamaican men - men who, by the way, served at Gallipoli - a story that has become dominated by narratives of nationhood by other countries, not least Australia and New Zealand.

With manpower at a premium, the power that would win or lose the war, guidelines were overlooked by medical examiners under pressure to fill quotas. Boys lied about their age, undersized and unfit men were waived through. To illustrate this Richard Smith shows the boys who found their way to Etaples.

But when it came to recruitment a man of African or Indian descent, no matter how tall and physically suitable were turned away - just as you could not see a black man defeat a white man in the boxing ring, so you could not have a black man alongside a man white at war and proving themselves to be the equal or more. For example, James Slim. tall, strong, ambitious and hopeful enlisted in the Coldstream Guards but was dismissed. Yet Prince Edward, of course, the Prince of Wales, though far too short for the cut, enlisted and given a commission.

In Cardiff the South Wales NSFU had a list of black men ready to join up but they were turned away despite or because of their ‘splendid physical physique’. Smith compares the men from the Caribbean to Vera Britain’s description of ‘dying men, reeking with mud and foul green-strained bandages, shrieking and writhing in a grotesque travesty of manhood’. (Brittain, p.423). There was a significant and burgeoning issue of parity of the black physique over the white. Although for some this physical prowess simply played into the view of the African as being ‘animalistic’ and sub-human - it's a surprise that the likes of Walter Tull could thrive and become celebrated. There was a struggle in society, an inferiority complex even when it came to the physique, character, morality and intelligence of the races.

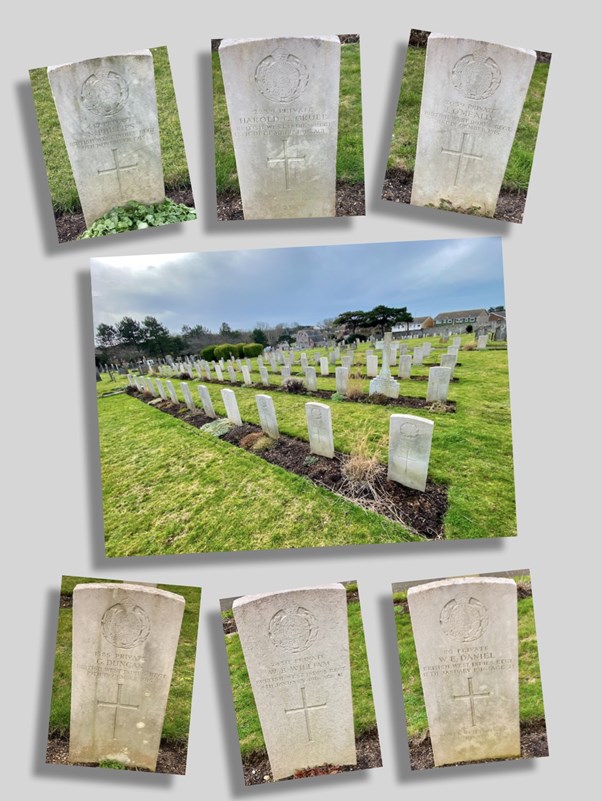

Many hundreds of Jamaican men forming the BWIR trained in Seaford on the Sussex coast. If they could survive the dreadful weather and poor living conditions they were posted to labouring jobs in the middle east.

Though class, not colour could at times be the barrier, the Cardiff Pals did not want miners or blacks - it was supposed to be a regiment of ‘for the better sort’ - white collar clerical workers rather than blue collar labourers.

Yet by law a British born citizen no matter their colour, could join the navy or army. The navy took men and put them into engine rooms to shovel coal. The army took men and put them to work as labourers.

Far from being a bolt from the blue, there were plenty of premonitions ahead of the First World War and how behaviours would play out. Germany had financed the Leconte and Simon revolutions in Haiti between 1908 and 1912. Their empirical ambitions were long in the making. Far from not having an army to field, the British Army could, would and planned to take soldiers from the Empire - from the martial races of India to fight and from the suppressed tribes of African and plantation workers in the Caribbean - labourers. In the ‘plantocracy’ of Jamaica as Smith describes it, there was an attachment to the crown (p.39).

The West Indian Regiment (WIR) were designated ‘native’ - troops were largely reserved for labouring roles, though not without their dangers, such as roading mending and hawling shells. The British authorities, like any from China, Jamaica or different parts of the Indian subcontinent, had their own ideas of where the different racial types were most suited - amongst other tasks, for example, Jamaican men were sent to Egypt to guard Turkish prisoners while the 1BWIR fought in Palestine (p.89)

In Britain, as in America, there were race riots after the war - resentment that anyone with a black face may have a job and expect to keep it while white men returned from battle. That said the journalist in the Stratford Express (16 August 1919 p.6) could still write that ‘the Jamaicans were British subjects - and entitled to protection as much as any other of His Majesty’s subjects.

Yet there were countless injustices, for example, estaminets were out of bounds to the Chinese and South African Labourers and when in March 1916 a ship with Jamaican labourers on board deviated to Nova Scotia it left 107 with frostbite and amputations.

The treatment of BWIR veterans in Taranto by a South African General Carcy-Bernard were terrible - almost the equal of white supremacist Generals in the AEF.

29 April 1919 There was fighting between white AEF troops and Black WIR troops at Winchester. (p.139) There had to be an appeal by the Mayor to entertain the visitors. (Hampshire Observer 3 May 1919 pp.4,5)

REFERENCE

Brittain, V (1979) Testament of Youth

Black Poppies > https://bit.ly/3a0S6Bo

Seaford. October 1915 - March 1916.

West Indian Committee Circular 539, 9 May 1917

J Johnson Abraham (p.186) ‘Surgeon’s Journey’ (1957) The black dandy and the troupe of the Black rapists.

Pte. Herbert Clarke, A Jamaican volunteer executed August 1917.

Story of Ernest Nembhard pp.115-116 - reported attempted rape of a farmer’s wife.