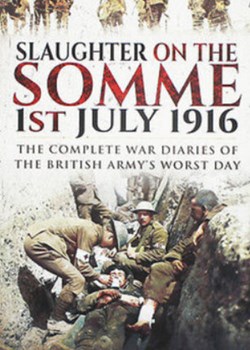

Slaughter on the Somme 1st July 1916

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Slaughter on the Somme 1st July 1916

Slaughter on the Somme 1st July 1916

The Complete War Diaries of the British Army's Worst Day

Martin Mace & John Grehan

(South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2016; first published 2013)

Softback £16.99

514 pp, including middle section of b/w photos, and six maps.

Contents also include List of Battalions; List of Abbreviations; plus index.

The first day of the Battle of the Somme. The massed Allied artillery fell silent… to be replaced by the sound of hundreds of whistles being blown. At 0730 hours on 1 July 1916, an army of British soldiers climbed out from their trenches on the Western Front, and made for the German positions opposite.

As we all know only too well, by the end of that day, more than 60,000 of those troops were casualties – a third of whom had died for their country. 1 July 1916 would become generally described as the worst single day in the British Army’s history; ‘the Somme’ would take root in the nation’s psyche. Some of the battalions involved met with varying degrees of success; others had suffered heavy losses for limited or no gains; a few had for all practical purposes ceased to exist. A volunteer citizen army went crashing headlong into the reality of modern warfare; and the British Army would never be quite the same again.

This unique book - ‘for the first time ever’ as the blurb on the back cover points out – brings together the full text from all the war diary entries for the 171 British battalions that went ‘over the top’ on that fateful day. The two men responsible for this feat of dedicated transcription have both had long standing involvement in the field of military history. Martin Mace has more than twenty years’ experience, while John Grehan has authored more than 150 books and articles on military subjects. Mace developed the idea for ‘Britain at War’ magazine, with which Grehan has also been involved.

What Mace and Grehan have done here is precisely what it says in the subtitle – transcribed the official war diary entries for 1 July 1916 of each of the battalions that took part in the attack. As readers will be aware, a war diary is an official daily record of the operations, reports, orders and related events and administration, written up for each unit by an appointed (usually junior) officer. They are not in any way personal diaries; a unit on active service was required to maintain this authorised account of its activities. The quality and content of each diary varies considerably. Some are very brief or concise, perhaps scribbled hastily in pencil by an author caught up in the confusion of battle; others may have been typed up in considerable detail after the events described. The crucial point is that these records of that first day of the offensive were written at the time or very soon after; by someone directly involved in or very close to the actions that took place.

Equally important for us, the readers, is that Mace and Grehan have also included the texts of supporting papers appended to the diary entries. These personal accounts and operations reports provide added detail which can often help set the unit’s actions in a broader context; or give an opportunity for some initial reflection upon the unit’s experience.

The result is a comprehensive collation of the immediate – and first hand - authorised histories of the attack launched on 1 July 1916. The diary entries and the appended reports are set out word for word from the original text archived at Kew. There has deliberately been no attempt by Mace and Grehan to edit or summarise what was written. The volume therefore stands muster as a most valuable reference work for anyone looking to research the opening of the Battle of the Somme. As someone who has spent time poring over original war diaries at the National Archives at Kew, I will always choose the personal reading of the actual document to be the most satisfying way of engaging with the history of the Western Front. It will certainly help you to appreciate this book if you have had the experience of reading some war diaries at first hand – so that you can bring to mind the feel of the paper, the hazy typewriter print or blurred pencil – all adding to that sense of becoming ever closer to the events described.

While the book’s main value is for reference purposes, I found real satisfaction in working my way through page by page, from the beginning. The successive accounts develop into a dense and multi-layered vision of the experience of the British soldiers that day. The records are variable in quality and detail – they can sometimes present as confusing or conflicting - perhaps frustratingly brief or with unnecessary detail. However this pot pourri of histories only adds to the sense that, taken collectively, the book probably represents the closest one can get to appreciating what the experience meant to those directly involved – before, during and immediately after the opening day of battle.

What also comes through for me – always present yet not always stated directly – is the sheer bravery, fortitude and commitment of the troops involved. The majority were not regular soldiers, they were volunteers from all walks of non-military life, but they gave of their best and for belief in a cause or principle which does not fit with the modern perceptions of the First World War as futile or senseless.

I shall always look back on July 1st with pride and sorrow because it was humanly impossible to do more than the [56th] Division did, sorrow for the hundreds of gallant Londoners who laid down their lives in a desperate attempt to achieve the impossible… That the ground gained could not be held was due to the cutting off of help and ammunition by the furious and sustained shelling…

The spirit shown and maintained must always make London look with pride on the part taken by its sons in the Battle of the Somme.

(War diary, 1/13 Battalion (Kensington) London Regiment,

A report on the attack on Gommecourt,

1 July 1916, C.S.M. A.J. Evans)

As always when I read a war diary, I found that the lack of sentiment and the sense of detachment in most of the entries actually deliver for me the exact opposite – I care passionately about the author and the fate of the men of whom he writes. To the great credit of those involved, there are many diary entries or appendices that include practical comments on the lessons to be learned from the experiences on the opening day’s failures; and suggestions on how future attacks could be improved upon. Often there are references to the importance of continuing the fight, as a fitting act in memory of those comrades in arms who had lost their lives. I feel humbled by the sheer stoicism of these people caught up in the maelstrom – this ‘let’s roll our sleeves up and get on with it’ response to what seems the worst kind of nightmare.

The body of the book is organised through a chapter for each of the six army corps involved in the battle. The chapter opens with a summative history of the role of the corps and its constituent divisions in the build up to the battle; followed by an overview of the particular events on the opening day. There is also a short reference to the perspective of the opposing German forces. The chapter then proceeds with the war diary for each of the battalions making up the formation, working in alphabetical order.

The final presentation of the book could have been slightly improved. There is a copy of the Official History maps (not always easy to read given the reduced scale required to fit on one page of the book), one for each corps sector, located at the start of each chapter. However an overview map of the front for the opening day of battle, showing initial dispositions of all the corps and key locations, would have been useful. There is also no order of battle provided so that it is necessary to try and have this information to hand on order to track how the actions of one battalion may relate to other units; or to check the relevance of references in one war diary to other battalions, brigades etc. The index of ‘military formations’ does provide some help for potential researchers; but it only helps with specific unit references. So the entry for a brigade only lists pages where that brigade is directly named – it does not allow the reader to locate all references to the battalions of which the brigade was formed, or the division of which it was part (hence the need for an order of battle). However I agree that these are minor points which can be addressed by having the appropriate maps and ORBATS somewhere close at hand. The index does also include a helpful list of place names.

My only real complaint is that title… particularly the use of the word ‘Slaughter’.

One of the book’s main achievements is to demonstrate the complexity of what took place on that day – the various planning and preparations, the heroism and courage, the different tactical attempts, the limited successes and the heavy loss of life. Others may disagree but I think the title could have tried harder to reflect this range of experiences; it does not do justice to the powerful and complicated picture that emerges from the book’s contents.

So, with that off my chest, I can now urge you to go out (or click on the mouse – though I always encourage supporting your local bookseller) and get a copy of this book - but do not just put it on your bookshelf to use for reference. Read it – it can be difficult at times (emotionally and textually) but so very worth the effort. Despite – or for me, because of – the range of quality and content in the diaries, I just found this collection of the human experience to be wholly compelling.

Review by Dennis Williams

20/10/2016