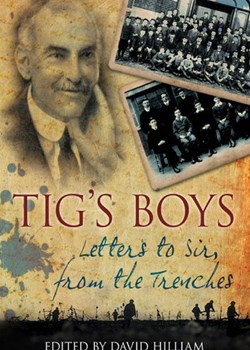

'Tig's Boys - Letters to Sir from the Trenches'

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- 'Tig's Boys - Letters to Sir from the Trenches'

Edited by David Hilliam

ISBN: 978 0 7524 6331 5

188pp with illustrations

David Hilliam has edited a remarkable collection of interesting and often moving letters that were written by the boys of Bournemouth Grammar School to their headteacher, Dr Edward 'Tig' Fenwick and published in the school magazine between 1914 and 1918.

Like many local historians, to whom we often owe a hidden debt, he has organised and recorded the words of these young soldiers and made their thoughts and their responses to the horrors they were facing available to a much wider readership.

There have been many attempts to capture the history of the First World War through the words of the ordinary men who experienced it first hand. Max Hastings, for example in Forgotten Voices of the Great War, [London, Ebury Press 2002], used interviews held by the Sound Archive of the Imperial War Museum to capture the intensity of what fighting and being part of the huge conflict was like. These letters are part of that process; they show us the minutiae of daily life in the trenches and behind the lines and reflect the views of privates, officers, artillerymen, machine gunners and members of the Royal Flying Corps.

The often mundane, fine detail of the letters not only gives us a personal response from each individual soldier but also suggests a much wider and more universal appeal. The writers' lives and deaths, their opinions and their descriptions of killing rats, rescuing tanks and playing 'footer' with shells falling amongst them is universal, because millions of men had exactly the same experiences.

Their childlike enthusiasm, naivety and bravado is, in hindsight almost tragic.

For example, in a letter from the school magazine of July 1915, Second Lieutenant Henry Budden describes his trench howitzers as 'very nice little toys ....' . he goes on to describe a fatal shell burst almost as if it was part of a playground scuffle: ' One of them [shrapnel shells] blew up 20 of my platoon and my escape was marvellous. I was right in the middle of a group of 25 men, 14 of whom were killed and seven wounded, but I was only knocked down by a sod of earth and was not one whit the worse for my fall.' Despite an almost overbearing optimism, his letter is both sad and poignant as he was killed four months later.

In fact 98 of the ex-Bournemouth Grammar School pupils and teachers died in the war, which meant that on average there was one death every fortnight. The oldest, Private Sydney Seeviour, who was awarded the Military Medal, was 30 and the youngest, Pioneer William Alder, was 17.

What is really interesting and what makes this book much more important and 'universal' than many other local studies is that 'Tig' Fenwick himself - the headmaster - also has a voice, and he not only shares his views in the school magazine at the beginning of the war and at the end but also in the many moving obituaries he wrote for the unfortunate boys and teachers who were fatal casualties.

I was occasionally reminded of the school master in All Quiet on the Western Front, who, in his unthinking patriotism, persuades many of his pupils to go off to fight and, of course, to die. There are elements of a rather naive and unreserved support for the war in some of 'Tig' Fenwick's words but in other ways he represents a more modern approach when, for example, he recognises the importance of fighting the Germans and winning.

He says: '..... with the Germans and with them alone, rests the blame for this appalling catastrophe' and, '.... there can be no end to the conflict until the Prussian military despotism has been so completely crushed as to be incapable of further inroads on the world's peace.'

In contrast to these strong views, he was also capable of great gentleness. For example, when he wrote about the death of William Alder, he said: 'Of all the sacrifices which the war has made so painfully familiar to us, none is more piteous than this - the spilling of the life blood of a boy, scarcely more than a child of 17 years.'

The photographs of some of the letter writers add an extra dimension to their words but the more general photographs add little to the many tragic stories and could have been more original.

Like many letters from soldiers there is a certain amount of blandness and ordinariness caused in the first instance by the problems of censorship and also by the fact that although these were, by all accounts, clever, literate ex-pupils, they were not historians or great writers and, of course, how could they possibly describe or want to describe the indescribable?

It is a measure of David Hilliam's skill that he converts the often very simple letters into a stirring chronology of bravery and suffering. The book is well worth reading and has been extremely well researched with some excellent dates, facts and figures that allows readers to place the writers in context, understand what happened to them and to see how many were decorated for bravery.

Reading between some of their lines can help us realise how the writers' views changed as the war dragged on. In the very first letter in March 1915, Arthur Wolfe says as he came out of the line - 'after a rub down, a good strong dose of rum, plenty of food and twelve hours sleep we felt very much better.'

The last letter in the collection, from Lieutenant J S Hughes in December 1918, says, 'I feel rather stunned to find that I've come out with two arms and legs and more or less sane'. Perhaps it is the 'more or less sane' that says it all about these young 'heroes' who were bursting with enthusiasm and vitality and who, with millions of others, fought through the carnage and helped save our world.

Reviewed by Roger Smith