Britain's Most Decorated Soldier in the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Britain's Most Decorated Soldier in the First World War

There are many categories and definitions of ‘hero’, but the main thread is associated with physical and moral courage, usually envisaged with aggression and typically armed action. This is only part of the story. There have only been three VCs with Bar awarded, and two of those were earned during the First World War and both by Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) Doctors: Captain Arthur Martin-Leake and Captain Noel Chavasse. As a retired RAMC Officer I am rightfully proud of their extreme courage; both were forces of nature.

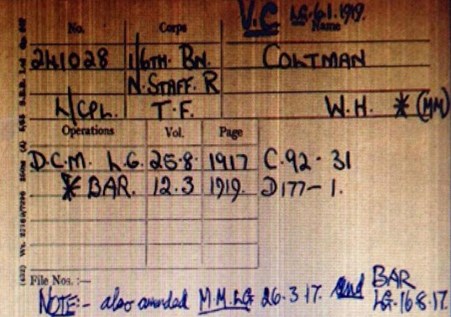

However, there were many other medical heroes of the First World War, and not only members of the RAMC since all Regiments had their own ‘cap-badged’ stretcher-bearers. One was Lance Corporal (LCpl) William Harold Coltman VC, DCM and Bar, MM and Bar (and a French Croix de Guerre which I believe he never wore). His story is perhaps little known but is worth telling.

Bill Coltman was born at Rangemore, a village on the outskirts of Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, on 27th December 1891. He was the youngest of nine children born to Charles and Anne Coltman. He had five brothers called Henry, Joseph, George, Samuel and Herbert Leonard. His three sisters were called Sarah Elizabeth, Annie and Frances. William was baptised at All Saints Church, Rangemore on 27th December 1891. He went on to work as a market gardener. Bill became a member of the Plymouth Brethren, and taught in the Sunday School in the village of Winshill. Coltman volunteered for the British Army in January 1915 and served in the 1st/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's). This was a Territorial Force (TF) Battalion, embodied in Burton-on-Trent. The Battalion deployed to France on 4th March, as part of 137th Brigade, 46th (North Midlands) Division, which was the first TF Division to arrive complete into a theatre of war.

Bill never fired a shot in anger. He couldn’t as he was strict Plymouth Brethren and a devout pacifist but he was definitely not a conscientious objector. He was (as an infantryman) issued with a rifle, and this can be seen in the photograph below (Bill Coltman is on the far right). You will note his short stature (5’4” on his enlistment papers) but he was stocky and clearly fit which was necessary for a stretcher-bearer, as we will see.

After spending a night trapped under heavy fire in a shell-hole listening to the cries of wounded soldiers he vowed never again to shoulder a rifle. The next morning, he submitted a request to retrain as a stretcher bearer.

Being a stretcher-bearer (SB) was by no means a ‘cushy’ option. There were 16 for a Battalion of (nominally) 1 000 men. Their job was to provide immediate life-saving first-aid and then evacuate the wounded from the front line to the Regimental Aid Post (RAP), which was manned by a RAMC Regimental Medical Officer (RMO) and a small number of Medical Orderlies. Here the casualty was triaged and given further first-aid treatment. They were then evacuated by RAMC SB from the supporting Field Ambulance (a unit, not a vehicle) to the Advanced or Main Dressing Station for further triage and treatment.

But casualties had to get there first! In heavy ground each stretcher might need six or eight bearers and it was not unusual for them to work in teams in relays (see below). Carrying the ‘dead-weight’ of a casualty is not easy (I know as I’ve done it!). These images show the conditions they had to cope with.

The bearers underwent six weeks’ training in basic medical care and stretcher-drills and were then given regular update training by their RMO. They were capable of dealing with haemorrhage, immobilising fractures and shock, and would have talked to the casualty during evacuation to reduce their anxiety. It was an advantage that they were dealing with their Battalion ‘mates’ so they’d have known each other. The poem at the beginning of this article illustrates the typical SB experience. Of course, they had to do all this frequently under fire, and their only ‘protection’ was afforded by their ‘SB’ armband which was worn on their left arm. Note the RAMC SB wearing a ‘Geneva Cross’ armband.

Not all of them made it by any means:

But back to Bill Coltman and his achievements. He was Mentioned in Despatches in 1916 for his work as a SB supporting his Battalion during the Battle of the Somme (when the 46th Division did not perform well).

The Military Medal (MM) was gazetted when awarded but no citation given. Coltman was still a Private at the time of this award. The award was made for rescuing a wounded officer from no man’s land in February 1917. The officer had been commanding a wiring party during a misty night. The mist cleared and the party found themselves under fire, the officer was wounded in the thigh and Coltman immediately went out to bring the casualty in.

His second award of the MM was gazetted in August 1917. This was for conduct behind the front lines in June 1917 and covered three separate instances of gallantry in a short period. On 6thJune an ammunition dump was hit by mortar fire causing several casualties, and Coltman took responsibility for removing Verey lights from the dump. The following day he took a leading role in tending men injured when the company headquarters was mortared. A little over a week later, a trench tunnel collapsed trapping several men. Coltman organised a rescue party to dig the trapped men out.

Bill’s first award of the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM) was made for gallantry over a period of days in July 1917. The London Gazette citation reads:

Conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in evacuating wounded from the front line at great personal risk under shell fire. His gallant conduct undoubtedly saved many lives, and he continued throughout the night to search for wounded under shell and machine gun fire, and brought several in. His absolute indifference to danger had a most inspiring effect upon the rest of his men.

His second award of the DCM was made for his conduct in September 1918 (only a week before his actions that earned him the VC). The citation reads:

On the 28th September, 1918, near the St. Quentin Canal, near Bellenglise, he dressed and carried many wounded men under heavy artillery fire. During the advance on the following day he still remained at his work without rest or sleep, attending the wounded, taking no heed of either shell or machine-gun fire, and never resting until he was positive that our sector was clear of wounded. He set the highest example of fearlessness and devotion to duty to those with him.

Of course, the pinnacle of his heroism was the award of the VC.

There was nothing they could do.

Wounded soldiers cried out for help as they lay scattered beneath Mannequin Hill. But with enemy machine gun and shell fire raining down from above, their pals in the 1st/6th North Staffordshire Regiment had no choice but to abandon them – or face annihilation.

Reluctantly, prompted by their officers, the unharmed soldiers and walking wounded withdrew from the ferocity of the enemy attack, leaving a handful of their mates behind. These were men who were too badly wounded to walk or even crawl away from the enemy guns. But the German fire raining from above meant that any rescue attempt would sacrifice more lives.

It was just a few days after the North Staffords’ glorious victory at the St Quentin Canal. In comparison, the follow-up assault on the Beaurevoir-Fonsomme Line, known as the Battle of Ramicourt, was expected to be easy.

It was anything but. German infantry put up a surprisingly stubborn line of resistance. Machine gunners had fired at the advancing British troops from a series of sunken lanes and individually dug rifle pits, or from well-constructed concrete shelters.

Yet, the Battalion had reached the Beaurevoir-Fonsomme Line, which was effectively a support trench for the Hindenburg Line, and their bayonets had been bloodied in the charge. They had captured all their objectives.

But heavy fire was poured on the North Staffords by enemy soldiers above them on Mannequin Hill. At risk of being cut-off and surrounded by an enemy counterattack, officers had no option but to order the men to retreat – and the weight of enemy fire meant there was no choice but to leave a few scattered wounded behind.

Coltman heard from his retreating comrades that wounded men had been left behind. So, he set out, alone, back along the valley in front of Mannequin Hill in search of those unfortunate soldiers.

The German army still occupied the high ground, the threat from heavy artillery and machine gun fire remained – but Coltman made his way towards the gunfire, zeroing in on the cries of the nearest wounded soldier.

This man had no doubt seen his comrades withdraw. He would have known his wounds were serious, perhaps fatal, and would have been in agonising pain. Perhaps he had given up all hope of survival.

Then suddenly, from nowhere Coltman was alongside, pulling out his first aid pack and patching up his wounds the best he could. He then hauled the wounded soldier onto his back and carried him back to the British lines.

Handing this man over to other stretcher-bearers to carry to the RAP, Coltman went back. Into the face of machine gun and shellfire yet again, he searched the valley until he found another injured soldier and carried him back. He then went out again, and once more returned with another crippled infantryman.

For 48 hours he kept up his efforts, until finally (exhausted) he lay down to rest.

His citation for the VC reads:

For most conspicuous bravery, initiative and devotion to duty. During the operations at Mannequin Hill, north-east of Sequehart, on the 3rd and 4th of Oct. 1918, L.-Corp. Coltman, a stretcher bearer, hearing that wounded had been left behind during a retirement, went forward alone in the face of fierce enfilade fire, found the casualties, dressed them and on three successive occasions, carried comrades on his back to safety, thus saving their lives. This very gallant NCO tended the wounded unceasingly for 48 hours.

Coltman was invested with his Victoria Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 22nd

May 1919. After his investiture (see below) he found out that there was a welcome home party at Burton train station for him, so he got off a stop earlier to ‘avoid the fuss’!

Note his unique medal card below, and his impressive ‘rack’.

After the war, Coltman returned to Burton and took a job as a gardener with the town's Parks Department. During the Second World War he was commissioned into the Army Cadet Force (ACF) in 1943 and commanded the Burton detachment. He resigned his ACF commission in 1951. Bill retired in 1963 and died at Outwoods Hospital, Burton, in 1974 at the age of 82. He is buried in the churchyard of St Mark's parish church in Winshill with his wife Eleanor May (née Dolman).

His medals, including his Victoria Cross, are on display at the Staffordshire Regiment Museum, at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, Staffordshire (which was his Regimental Depot). At the museum there is a replica First World War trench named in his honour. Coltman House is the headquarters building for the Defence Medical Services at Whittington Barracks. The Burton Army Cadet Force and Army Reserve Centre is at Coltman House, Hawkins Lane, Burton.

There is a monument to Coltman at the Memorial Gardens, Lichfield Street, Burton. The Coltman VC Peace Wood is at Mill Hill Lane, Winshill, and a road has been named in honour of Coltman in Tunstall.

Bill Coltman was undoubtedly heroic and a man of great faith and principles. He is (I believe) worthy of wider remembrance and recognition, and indeed admiration. Truly a weaponless warrior.

The Stretcher Bearer

My stretcher is one scarlet stain,

And as I tries to scrape it clean,

I tell you wot--I'm sick with pain

For all I've 'eard, for all I've seen;

Around me is the 'ellish night,

And as the war's red rim I trace,

I wonder if in 'Eaven's height,

Our God don't turn away 'Is Face.

I don't care 'oose the Crime may be;

I 'olds no brief for kin or clan;

I 'ymns no 'ate: I only see

As man destroys his brother man;

I waves no flag: I only know,

As 'ere beside the dead I wait,

A million 'earts is weighed with woe,

A million 'omes is desolate.

In drippin' darkness, far and near,

All night I've sought them woeful ones.

Dawn shudders up and still I 'ear

The crimson chorus of the guns.

Look! like a ball of blood the sun

'Angs o'er the scene of wrath and wrong. . . .

"Quick! Stretcher-bearers on the run!"

O, Prince of Peace! 'ow long? 'ow long?

Robert W. Service (1874 – 1958) – British-born Canadian Poet - known as “Canada’s Kipling” who was a stretcher-bearer with the American Red Cross in the First World War.

Article contributed by Lt Col Ken Roberts (Retd) OSt MSc BSc (Hons), former Surgeon General's Principal Staff Officer