Götterdämerung – June 1919 The End of the German High Seas Fleet by Robin Brodhurst

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Götterdämerung – June 1919 The End of the German High Seas Fleet by Robin Brodhurst

The surrender and scuttling of the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands is a perfect example of the folly of war, of man’s inhumanity to man, but also of the ingenuity of the human mind, featuring, as it does, two men who are perhaps archetypal examples of great British eccentricity and thus to be celebrated.

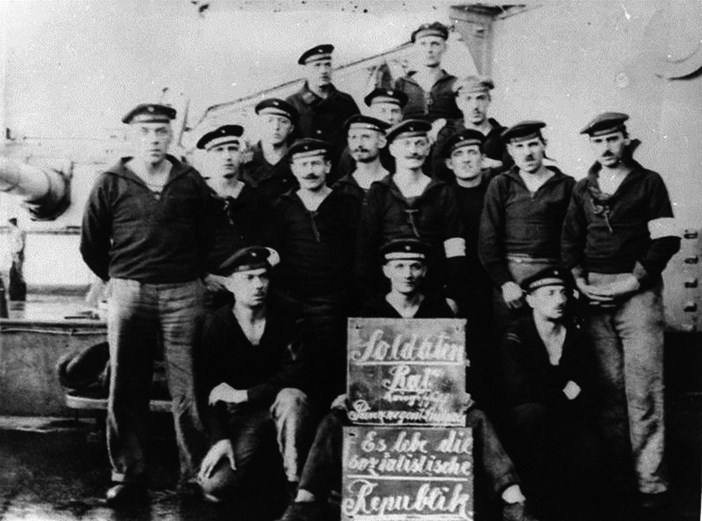

Kiel Mutiny: Sailors on the deck of the SMS Prinzregent Luitpold display a sign saying: ‘Soldier’s council, Warship Prinzregent Luitpold. Long live the socialist republic.’ Bundesarchiv, Bild 183–J0908–0600–002 via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183–J0908–0600–002,_Novemberrevolution,_Matrosenaufstand.jpg

Morale

To quote an American journalist in May 1916, ‘The German fleet assaulted its gaoler and then fled back into its cell’. After the battle of Jutland it is not true to say, as many do, that the High Seas Fleet never came out again. It is, however, true to say that they never came out again after August 1916 in order to offer battle to the British Grand Fleet. The effect that this must have had on the morale of the German sailors is incalculable.

In Volume 5 of his From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, the great American historian Arthur Marder states:

‘The German Navy collapsed in part because it overlooked the fundamental truth that the human factor is always the decisive one. That their lower deck personnel proved unequal to the strain of war is obvious. The real weakness of the German naval system lay in the gulf that divided officers from rating. Thus, when the crews of the High Seas Fleet went ashore at Wilhelmshaven, their officers did not take all the trouble that the British did to give them opportunities for recreation and give them outside interests. And they maintained an aloof attitude towards their men.’ (1)

A contemporary British officer said much the same:

‘The German officer was much too serious in his dealings with his men. To him ‘war was war’, and nothing more. No cricket, no boxing, no football, no concerts etc., to take the men’s mind off their plight – no sympathy between officers and men – just the war.

Contrast this with the British naval officer’s idea of discipline. Men and officers played together, boxed each other, ran races, pulled in the same boats, got up concerts and otherwise amused themselves – even though there was a war on. ‘All work and no play make Jack a dull boy.’ That was the difference – the vital difference – between the two navies.’(2)

This indifference to the human factor is also seen in the harsh discipline, bad food and general disregard for the sensibilities of the men. To these we can add the monotony induced in the stultifying routine, and the inactivity of the Fleet, completing the picture of the sharp decline in the morale of the German lower deck. However, that decline did not extend to the submarine crews, who lived cheek by jowl with their officers, in the cramped conditions of the U–boats. Linked to this was an absence of any naval tradition. This meant that frequently their first instinct on meeting an enemy force was to turn for home. Faced with the prestige and overwhelming strength of the Royal Navy, the Germans hardly ever handled their surface fleet with enterprise in the war. They had no confidence in naval victory, and they were afraid to sustain ship losses.

Calculated risk

It is not surprising therefore that when the High Seas Fleet was ordered to sea in November 1918 its morale collapsed. The German Admiralty had a sensible plan, intended to influence the peace negotiations decisively. The German plan was simple, bold and risky. Light cruisers and destroyers would launch a series of raids on the Thames Estuary, designed to draw the Grand Fleet south from its Scottish bases. Minefields and submarines would lie in wait for them. The High Seas Fleet, under Admiral Hipper, would put to sea with every available capital and supporting ship to assault what it was hoped would be an already diminished and disrupted Grand Fleet at a time and place of the Germans’ choosing. It did not matter whether the Germans won or lost, just that they inflicted damage on the Grand Fleet. It was not a madcap final fling by the Prussian Officer Corps to salvage its honour; it was a calculated risk, strategically and tactically sound.

The High Seas Fleet set sail on 29 October for its usual assembly point at the Schillig Roads, in slightly greater strength than it had possessed at Jutland: 22 capital ships, 12 light cruisers and some 70 destroyers. However, at this point the plan collapsed. They had reckoned without the war–weariness and low morale of the crews. Mutiny broke out among the crews of the battleships and soon became general, forcing Hipper to order a return to port. By the end of the first week in November Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils on the recent Soviet model, had been set up in Kiel and Wilhelmshaven and red flags were hoisted at many points along the North Sea and Baltic coasts. The similarity here to the role of the Russian sailors in the October 1917 revolution appeared striking. Similar outbreaks happened all over Germany, and the main naval bases were reduced to a shambles, remaining in such a state even though the Government promised that the navy would not be sacrificed.

Dominant figures

Portrait of Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss, probably taken when he was in command of the East Indies and Egyptian Squadron, 1917. Courtesy IWM Q54783

In the Royal Navy there were two dominant figures: firstly, the excellent First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, who had succeeded Jellicoe on the latter’s dismissal on Christmas Eve 1917, but was seen by some as a mere stop–gap until Sir David Beatty could take over as First Sea Lord. Wemyss’ war had principally been in the Mediterranean, and he was highly efficient and, above all, courteous in the extreme. He possessed common sense, a sense of humour and great moral courage; all of which he would need.

Admiral David Beatty, posing deliberately for the camera with his hat at its famous ‘Beatty tilt’ shortly after his appointment as the Commander–in–Chief of the Grand Fleet. Courtesy IWM Q19571

Beatty was commanding the Grand Fleet. By October 1918 he was very keen to achieve two things. Firstly, he was desperate to achieve a naval victory over the High Seas Fleet, feeling more and more that the strategic victory achieved by Jellicoe at Jutland was flawed. Secondly, he was determined to become First Sea Lord immediately peace was declared. In this he had some justification as he was undoubtedly the most distinguished sailor alive, and he did become an extremely good First Sea Lord. However, his progress to the Admiralty was stormy, mainly due to his demands to be First Sea Lord on his own terms, and with very far reaching powers.

On 8 October the Allied Naval Council met with the Military Representatives of the Supreme War Council at Versailles to draw up draft armistice conditions. The Admiralty recommended that 60 German submarines proceed at once to specified Allied ports and remain there for the duration of the Armistice, and that ‘all enemy surface ships’ would proceed to specified naval bases and stay there during the Armistice. It was thought that 60 U-boats would be the maximum number which could put to sea.

The mood of the Admiralty and indeed of the whole Royal Navy, was grim. There was ‘a feeling of incompleteness’ to quote Wemyss. While the Navy had won a victory in many ways greater than Trafalgar, that victory was less spectacular. There had been no great decisive sea battle. A victory was necessary to salve British naval honour and to bring glory to the Grand Fleet. They were also upset that the British Army was claiming the credit for finishing off the Kaiser. They insisted that the surrender of the German fighting ships be a sine qua non. On the other hand, Wemyss was fully aware that the politicians and the army did not want the war to go on over another winter, and so he was busy ‘endeavouring to moderate the zeal of the Sea Lords.’

The Navy’s views on the naval conditions for an Armistice were laid before the Cabinet by Wemyss on 19 and 21 October. They differed from those of the Allied Naval Council, but were identical to Beatty’s views, except in one important respect: the Admiralty also considered that the blockade should continue. The conditions were these: the surrender to the Allies of:

Two of Germany’s three battle squadrons, containing the newest battleships – 10 – also the fleet flagship, the Baden

All 6 battlecruisers (including the Mackensen, which was, wrongly, thought to be completed)

8 light cruisers

50 of the most modern destroyers

All the submarines afloat

Wemyss explained to the Cabinet that ‘The submarine war has been carried on by the Enemy in contempt of the rules of International Law and of the dictates of humanity. In the interests, therefore, of International morality the first opportunity should be firmly taken of removing entirely out of his hand the weapon which he has so grossly misused.’(3) Beatty, like Wemyss, believed that the Armistice terms must be nearly the same as those they wanted to obtain in the peace terms, since he felt a resumption of hostilities after an armistice was not likely.

Terms

At the War Cabinet only Sir Henry Wilson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), supported the Admiralty. Lloyd George protested that the Navy’s terms amounted to ‘abject surrender’ and was supported in that by Haig, who explained that the effect on the morale of the Army of a rejection of the Armistice terms would be bad. Wemyss argued back that although the naval terms were stiff he did not see how they could be reduced, if the Armistice terms were to resemble the peace terms. The War Cabinet was anxious that none of the Armistice terms be of a character as to appear to humiliate the Germans unnecessarily, and this position was strengthened by President Wilson who opposed any excessive naval terms. He would agree to Germany handing over all her submarines but not her surface ships, and the War Cabinet adopted that position on 26 October as a guide to Lloyd George in his negotiations in Paris. The only change to the Admiralty position was to substitute 160 for ‘all’ submarines on Lloyd George’s insistence.

From that point politicians took the lead and the scene shifted to Paris where the Allied Naval Council met between 28–30 October to discuss the Admiralty proposals and those from other Ministries of Marine. Initial amendments to the British proposal were to substitute 160 submarines for Beatty’s suggested 50 and to delete the fleet flagship, Baden, so as to lessen German humiliation. All surrendered vessels were to be held in trust for final disposition at the peace conference. The existing Blockade provisions were to be continued.

These terms were presented to the Supreme War Council on the morning of 1 November. Immediately there was trouble, since the politicians – Lloyd George, Clemenceau and Wilson’s representative, Colonel House – with powerful support from Foch, wanted to whittle down the naval terms so as to make them palatable to the Germans. If the terms were too harsh the Germans would reject them and there would be another year’s fighting. What lay at the heart of this was a lack of knowledge as to how seriously Germany was defeated and how prepared she was to fight on. The military terms were also stiff and, as Wemyss reported, ‘the politicians want a softening somewhere’ and it looked as if it had to come in the naval terms. (4) Lloyd George also thought the Allied naval terms were excessive, proposing that the submarines, battlecruisers and light cruisers be surrendered, but that the battleships be interned in a neutral port. The conference accepted that as a compromise.

On the afternoon of 1 November, the Allied Naval Council discussed the views of the Supreme War Council. All the admirals, bar one, were opposed to changing their recommendations. Wemyss argued that the Germans would use the battleships as a pawn at the peace conference, and was heavily supported by the French Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS), Admiral de Bon. Only the American representative, Admiral William Benson, the US Chief of Naval Operations (USCNO), supported the politicians. His unspoken fear was that the British would be the beneficiary of any distribution of the surrendered ships. Internment, as opposed to surrender, would ensure that their disposition would be left to the Peace Conference.

However, the die was cast at the 4 November meeting of the Supreme War Council. Admiral Hope, Deputy First Sea Lord, who was present, believed that the Benson memorandum, arguing that the internment, as opposed to the surrender, of 10 battleships and 6 battlecruisers would increase the probability of acceptance of the armistice terms, had largely influenced the decision in favour of the disarmament and internment under Allied supervision of all surface ships. The politicians made it clear to the admirals that a decision had been made, and so the admirals succumbed to political pressure.

As regards the disposition of the German fleet, the naval terms now read:

Article XXII surrender of 160 submarines.

Article XXIII internment in neutral ports, or failing them, Allied ports, of 10 battleships, 6 battlecruisers, 8 light cruisers and 50 destroyers, the ships to be designated by the Allies and with only German care and maintenance parties left on board. The remaining ships to be disarmed. (The reference to Allied ports was a last–minute alteration in the draft conditions after it was realised that the neutral governments of Europe might refuse to receive the ships).

Article XXVI the Blockade to continue.

Article XXIX provided for the return of Russian warships in the Black Sea seized by Germany.

Article XXXI no destruction of ships or of materials to be permitted before evacuation, delivery or restoration.(5)

The duration of the Armistice was to be 36 days; it could be extended and was, regularly: on 13 December for a month, on 16 January for a month and on 12 February indefinitely.

Original conditions

The French military and British naval representatives – Foch and Wemyss second and third from right respectively – outside the railway carriage in which the Armistice was signed. Courtesy IWM Q43225

During the negotiations with the Germans, which lasted from 8 to 11 November, the German naval delegate, Captain Vaneslow, remarked that it was inadmissible that their Fleet should be interned, seeing that they had not been defeated. To this Wemyss replied that they only had to come out for that to happen! When Vaneslow told Wemyss that there were not 160 submarines to be had, Wemyss saw an opportunity to get what he had always wanted: all the submarines. Article XXII was so altered, in handwriting. It also transpired that the battlecruiser Mackensen was at least ten months from completion, and in no state for towing, so only five battlecruisers could be interned. On 12 December at the first renewal of the Armistice, the Allies demanded that the Baden be sent in place of the Mackensen. So, the Admiralty’s original conditions as regards both the U–boats and the surface ships were secured in the end.

The signing of the Armistice in Foch’s railway carriage at Compiègne was relatively straightforward. Foch only appeared twice: first to ask the German delegation what they wanted, in other words to make them ask for a cease fire, and secondly to sign the terms. The actual negotiations were left to his Chief of Staff, General Maxime Weygand and to Wemyss’ deputy, Admiral Hope. The famous picture of the signatories shows Foch, Weygand, Wemyss, Hope, and Wemyss’ naval secretary Captain Marriot in the front row and four French staff officers behind on the steps of the carriage. It is of interest to note that there was no US involvement in the signing of the Armistice because they were not part of the Entente Alliance, but, like Belgium, were only an Associated Power.

To the twin disappointments to Beatty of no fleet action and no surrender was added upset that Wemyss had not kept him abreast of every move in the negotiation, charging Wemyss with not taking him into his confidence, and not consulting him at all. The First Sea Lord gently explained ‘As for consulting you – well, I seem to have lived the last few days in motor cars and trains. Conditions were perpetually changing and it was physically impossible to keep you more au courant than I did.’(6) A better example of Beatty’s arrogance is hard to find.

‘Disarmed, dishonoured’

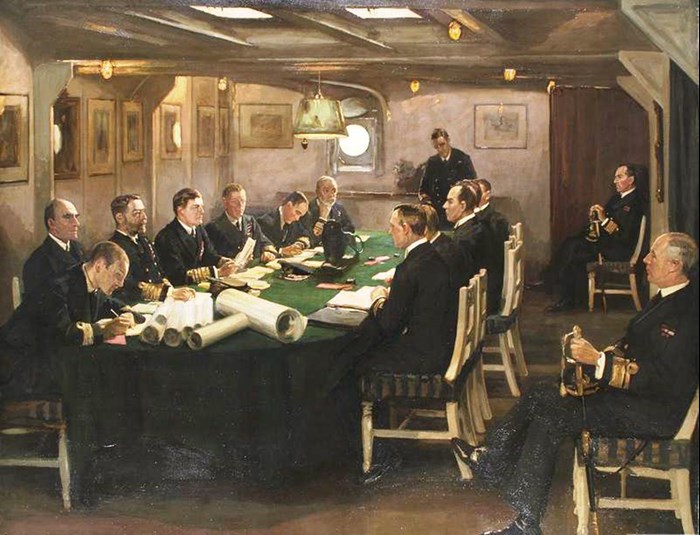

The End: Oil painting by John Lavery depicting the interior of the fore–cabin of HMS Queen Elizabeth with senior Royal Navy and German Navy officers sitting either side of a long table. Admiral Sir David Beatty sits fourth from the left holding a roll of paper in his left hand and reading out the terms of the surrender to the German officers, who sit opposite. Courtesy IWM ART 4219

The arrangements for the internment of the German ships went ahead rapidly. No European nation was prepared to accept them, and so Britain offered her services. On the evening of 15 November Hipper’s representative, Admiral Meurer arrived at the Firth of Forth in the light cruiser Königsberg to arrange the details. He and his four staff officers were received with icy formality by Beatty on board HMS Queen Elizabeth. By the evening it had been agreed that the submarines were to be delivered to Harwich under the supervision of Admiral Tyrwhitt, and the surface ships to Beatty in the Firth of Forth, from where they would be transferred to Scapa Flow for internment until the peace treaty determined their disposal.

By daybreak on 21 November the whole of the Grand Fleet had put to sea: 370 ships and 90,000 men in total. There was an armoured cruiser and two destroyers from the French navy, and the 6th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet from the US Navy (their Battle Division 9). They sailed in one line initially before splitting into two columns, six miles apart, each column composed of over 30 battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers. Contact was made with the Germans at 9.30am. The German fleet was in single line ahead: 9 battleships, 5 battlecruisers, 7 light cruisers and 49 destroyers, under the command of Admiral von Reuter in the Friedrich der Grosse. One destroyer, V–30, had struck a mine and sunk, the dreadnought König and the light cruiser Dresden were in dock and not seaworthy.

Oil painting by Charles Dixon of the light cruiser, HMS Cardiff, flagship of the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron, leading the main body of the German High Seas Fleet to the Firth of Forth prior to its formal surrender to Admiral Beatty. Astern of the Cardiff are the German battlecruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, Hindenburg, Derfflinger and Von der Tann

The light cruiser Cardiff led the German fleet down the gap formed by the two Allied divisions. Ships’ companies were at action stations, guns loaded but trained fore and aft. As Queen Elizabeth moved to her moorings the men of the Grand Fleet cheered Beatty, who acknowledged them by waving his cap. At about 11.00am Beatty signalled ‘The German flag will be hauled down at sunset today, Thursday, and will not be hoisted again without permission.’ Precisely at sunset (3.57pm) the German ensigns were hauled down.

By 24 November all the German ships had been inspected and were ready to move to Scapa Flow, and the surplus German crews were shipped back to Germany. Only 200 were allowed for each battleship and fewer for the cruisers and destroyers. By 27 November all 70 ships that had gone to the Firth of Forth were in their appointed anchorages at Scapa Flow. On 6 December the battleship König arrived direct from Germany, followed by the cruiser Dresden, hastily patched up and leaking badly, and the destroyer V–129. The seventy–fourth and last ship to arrive at Scapa, the battleship Baden arrived on 9 January 1919 to stand in for the incomplete Mackensen. So they sat, in Rear Admiral von Reuter’s words, ‘Wehrlos, ehrloss.’ ‘Disarmed, dishonoured.’(7)

‘Intention to sink’

A British Battle Squadron acted as guardships at all times. Armed trawlers and drifters patrolled the anchorage. Their orders were to watch for and to report at once if any of the German ships appeared to be sinking. There was no danger of the German ships raising steam and making for home as most did not have enough fuel to steam far into the North Sea. The one possible danger was a scuttling in violation of article XXXI of the Armistice, which said ‘No destruction of ships to be permitted.’ Rather to his surprise Vice Admiral Sydney Fremantle of the 1st Battle Squadron had received no instructions on the disposition of the interned ships and their crews at the termination of the Armistice, scheduled for 21 June 1919, but extended to 23 June, simultaneous with the time fixed for the signing of the peace terms. However, he did have in hand plans of his own to take over the ships on 23 June when he returned to Scapa Flow from an exercise.

Von Reuter had been informed unofficially by Fremantle that the Armistice had been extended to 10.00am on 23 June. However, he had already made his plans. He had read in an English newspaper that the original naval terms of the peace treaty had not been changed. He believed that the German government would reject the terms and the Allies would resume hostilities and move to seize the interned ships, and so gave orders that they were to be scuttled. There is some evidence that messages from the German Admiralty had reached von Reuter instructing him to scuttle his ships, but the initiative was almost certainly his. The plan was secretly distributed to all ships and was dated 17 June:

‘Sinking is only to take place (a) in the case of forcible intervention on the part of the English. (b) On the receipt of special orders from me ... It is my intention to sink the ships only if the enemy should attempt to obtain possession of them without the assent of our government. Should our Government agree in the peace terms to the surrender of the ships, then the ships will be handed over, to the lasting disgrace of those who have placed us in this position.’(8)

Written orders were sent to all his captains (by the British drifters!) on 18 June to make all preparations for sinking their ships on his signal. This occurred at about 11.20am on 21 June with the innocuous signal ‘To all Commanding Officers and the Leader of the Torpedo Destroyer Boats. Paragraph Eleven of today’s date. Acknowledge. Chief of Interned Squadron.’ This aroused no British interest and the German crews at once started to open sea–cocks and watertight doors. Nothing out of the ordinary was noticed until about noon, when it was noticed that the Friedrich der Grosse had taken a heavy list to starboard. At the stroke of noon, the German ships hoisted the German ensign on the mainmast. It was only at that point that it was obvious that something was happening.

On Reuter’s own flagship, the cruiser Emden, he could take little immediate action as there were two British drifters alongside delivering stores as well as a water–supply vessel, actually pumping water on board! When they cleared away, he gave the order to his captain at 12.10pm. One hour and forty minutes later there was still remarkably little to see. Reuter could hear a brass bell tolling. It was the ship’s bell of the Friedrich der Grosse signalling to the crew to abandon ship. At 12.26pm, with remarkable speed she turned turtle and sank, the first to go down.

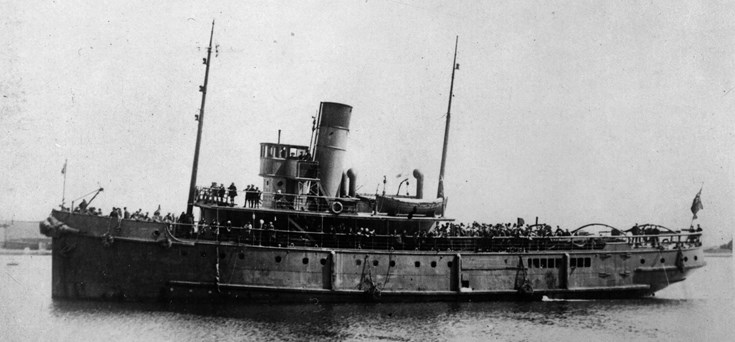

The best view of the morning was had by four hundred boys and girls of the Stromness Higher Grade School who were waiting for their outing on board the Flying Kestrel, a large tug–cum–tender which was under way at 9.30am. She crossed the channel between Stromness and Hoy and headed south, passing between the lines of capital ships and then along the lines of destroyers in the channel between Hoy and Fara, steaming at a leisurely pace to give the children a prolonged view of the ships. Suddenly, as she was approaching Lyness, a signal was received reporting that the German ships were sinking and ordering a return to Stromness at full speed, to land the children and return to the scene. The tender put about shortly after noon and headed north. It is the nightmarish contrast between the tranquil southward pleasure cruise and the headlong dash north through the scene of total chaos that made the experience unforgettable. One of them remembered a crewman shouting ‘Look! The Germans are flying their ensigns!’ The first ships they passed were the destroyers. ‘They were all at crazy angles. Some rolled on to their sides, others went down stern first or by the bow.’ Then they were in sight of the capital ships. An older girl recalled:

‘Suddenly without any warning and almost simultaneously these huge vessels began to list over to port or starboard; some heeled over and plunged headlong, their sterns lifted high out of the water and pointing skywards; others were rapidly settling down in the ocean with little more showing than their masts and funnels, while out of their vents rushed steam and oil and air with a dreadful roaring hiss, and vast clouds of white vapour rolled up from the sides of the ships. Sullen rumblings and the crashing of chains increase the uproar as the great vessels slant giddily over and slide with horrible sucking and gurgling noises under the water. The proud vessels slowly disappear with a long–drawn–out sigh.(9)

The Flying Kestrel with school children clearly shown aboard. It may be that the photograph was taken on 21 June 1919, the day the German High Seas Fleet was scuttled. Courtesy Orkney Library & Archive

SMS Bayern down by the stern and sinking at Scapa Flow. Courtesy IWM SP1625

As the Flying Kestrel ran for Stromness, she passed the Baden, still at her anchorage point, the most north–westerly of the fleet. The last impression on the minds of the children before they got ashore was the oddest, perhaps of them all. They looked back and saw a solitary sailor in white summer uniform dancing a hornpipe on a gun turret. The Baden for some reason was the last ship to start the work of scuttling. Thus, the Flying Kestrel, when she came surging back to the scene, was able to take her in tow and beach her before she had time to sink. Baden was the only capital ship which did not go down.

In terms of numbers the following ships were sunk:

10 out of 11 battleships

All 5 battlecruisers

5 out of 8 light cruisers

32 out of 50 destroyers

70 per cent of the ships. 95 per cent of the tonnage

The 22 ships which were not sunk were all beached.

The German crews were now treated as PoWs, and sent to a mainland camp. Before they departed Fremantle harangued Reuter on board his flagship Revenge about ‘the manner in which you have violated common honour and the honourable traditions of seamen of all nations’. He had probably forgotten Alfred Lord Tennyson’s immortal words about Sir Richard Grenville and his flagship, the first Revenge.

Sink me the ship, Master Gunner – sink her, split her in twain!

Fall into the hands of God, not into the hands of Spain.(10)

Salvage

So, we come to in many ways the strangest part of the story: the greatest salvage operation in history. Two days after the scuttling the Admiralty said they would be left to rot: ‘Where they are sunk, they will rest and rot. There can be no question of salvaging them.’(11)

The whaler Ramna stranded on the scuttled German battle Cruiser Moltke on 23 June 1919 before she was successfully refloated. Courtesy IWM SP1633

Not surprisingly, after nearly 5 years of total war, there was no shortage of scrap metal, and naval salvage experts pronounced that the wrecks were no hazard to navigation. The latter was soon proved wrong as small vessels began to run aground on them. In April 1923 the Admiralty changed its mind and said that it was prepared to consider tenders for raising some of the ships, and in June the first contract was agreed with Mr J W Robertson of Shetland County Council, giving him the right to raise four destroyers from the shallower water near Fara Island. The Admiralty charged £250 each. Later when the big ships were sold to other contractors it was possible to buy a battleship for £1,000. The last that was sold fetched £2,000.

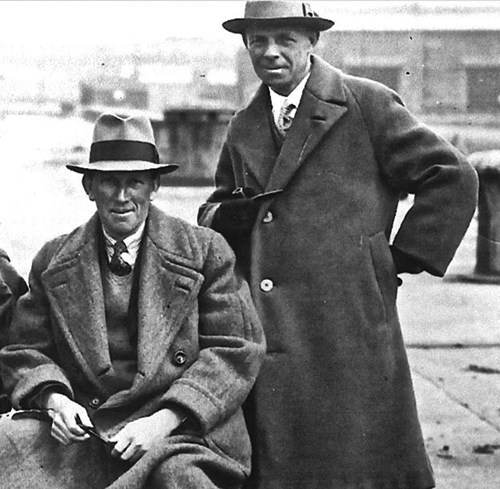

Ernest Cox, left, and his chief salvage expert Tom McKenzie

In 1924, before Robertson managed to lift his first destroyer, Mr Ernest Cox arrived in Orkney and announced that he had bought the Hindenburg and the Seydlitz along with 24 smaller ships. Eventually, he was to buy the rest and became known as ‘The Man who Bought a Navy’, the title of the book written about him. (12) His company Cox & Danks Ltd. won the contract against competition from several other firms. He was allowed to use the RN base at Lyness, virtually abandoned soon after the end of the war, where he installed cinema and wireless facilities for his workers and housed them in the bleak and down–at–heel naval huts. Cox is a classic example of the Victorian self–made man. The eleventh of thirteen sons of struggling Wolverhampton draper (and one can understand why he might be struggling with 13 sons), he left school at 13 and took a job as an errand boy, and in his spare time studied engineering books borrowed from the local library.

The upper–works of the German battle cruiser Hindenburg above the water at Scapa Flow. Courtesy IWM SP1635

By the age of 20 he was chief engineer at a Hampshire power station. He married the daughter of the owner of a Lancashire steel works, becoming a partner in the firm and developing it. He was a man of blunt speech, a brave and stubborn individual with a quick temper, short on modesty and long on hard work. In 1913 he set up Cox & Danks with his wife’s cousin, who put up the money while Cox supplied the expertise, making a lot of money manufacturing shell cases. After the war Cox bought out Danks and turned to shipbreaking at a yard on the Isle of Sheppey. He bought a German floating dock from the Admiralty for £24,000 and successfully broke up and sold off two scrapped British battleships. Short of work he took up the suggestion of a business contact to have a go at the Scapa wrecks. He eventually invested over £100,000 in the operation, buying tugs, cranes, pumps and diving gear. His best move was to employ a diver called Tom McKenzie as his chief salvage expert, who worked at Scapa Flow until 1939, ending the war as Commodore RNVR and Principal Salvage Officer, North West Europe. The only thing missing was business efficiency, about which Cox knew little and apparently cared less. It would eventually be his Achilles Heel. He hired specialist divers and workers from across Scotland, but most of the labour force was local, particularly important in the Orkneys in the 1920s and 1930s.

By August 1924 Cox had lifted three destroyers, while the smaller Robertson organisation was still lifting its first. By the end of the year Robertson had raised his four destroyers and took no further part in the salvage operation. Through 1925 Cox lifted more destroyers with 24 being raised in twelve months. He sold the resulting 23,000 tons of scrap for £50,000. The last destroyer broke surface on 30 April 1926. But this was a mere hors d’oevre compared to what was to come, with the epic recovery of the big ships.

Air–locks

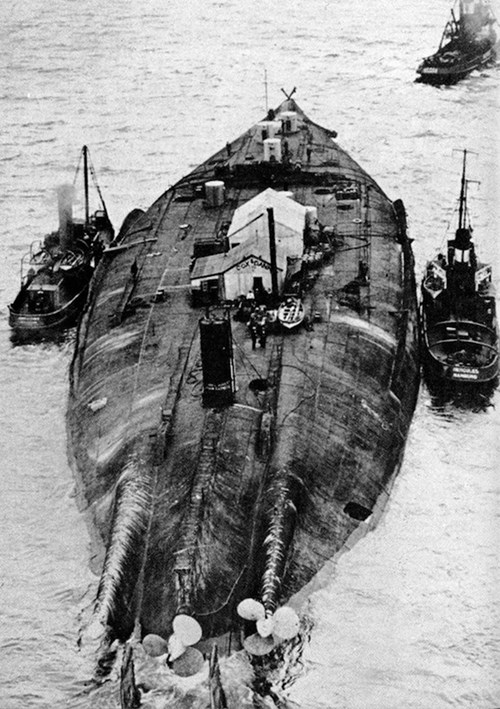

Air locks like chimneys were used to raise the Moltke. Here they are shown being used to raise the Kaiserin, the eight air locks secured by guy ropes. The tiny figure of the man to the right of the air lock nearest the camera indicates the scale of the operation

Corrugated iron huts erected on the upturned hull clearly show the names Cox & Danks

The first battleship to take their attention was the Hindenburg, so considerately sunk by her captain on an even keel with funnel, masts and superstructure rusting above the sea. Cox and McKenzie realised that a new technique would be needed, as the weight of the ship at 26,000 tons exceeded the combined displacement of all 24 destroyers lifted so far. The plan was for divers to patch all the holes found in the hull, pump her clear of water and use his two floating docks to lift her and beach her. About 800 holes had to be plugged and it took some 5 months to make the hull watertight, but then fish started eating the grease used to seal the plugs. Once the grease was made unpalatable, they tried again and then a gale flooded the ship. Each time they raised her she listed, so they attached cables to the mast, which then snapped. On 2 September 1926 she eventually rose to the surface, but a gale a few days later sent her back down. Uncharacteristically Cox then abandoned Hindenburg for the time being and moved on to the Moltke, which was to come within feet of being Cox’s nemesis, and produced one of the great salvage stories of all time.

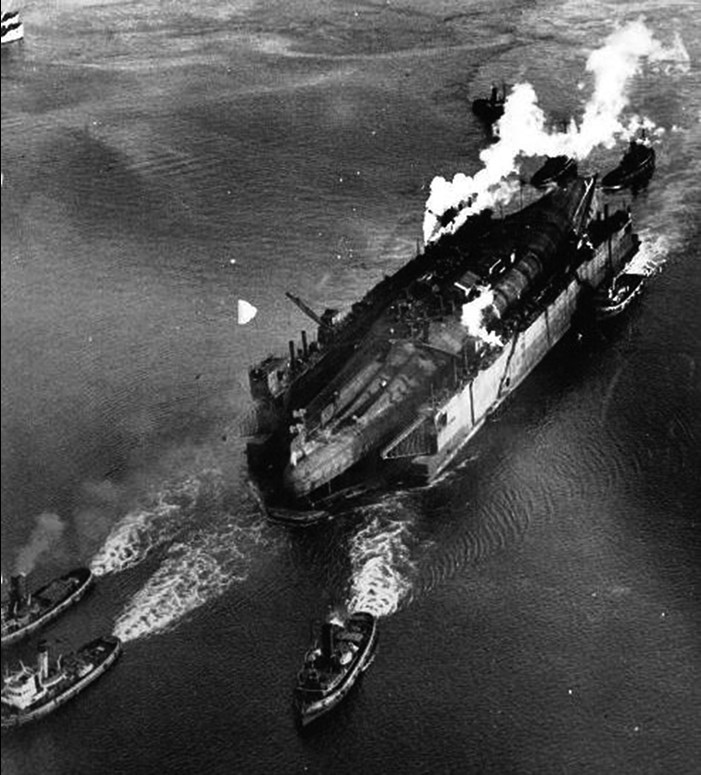

The Moltke lay upside down in about 80 feet of water, and at an angle which left part of her level with the surface at low water. To get at her plates Cox’s men had to dig through masses of marine vegetation. To raise her they used a method new to them, but not original: plug every hole in the hull and fill it with compressed air. Air–locks, like chimneys, made from old boilers welded together, were specially made at Lyness and welded to the hull and braced with guys, so that workers could get into the hull without losing air pressure, and divers could decompress in them. The sealing process was finished by May 1927, and she rose slowly while being sucked free from the mud, and then came to the surface in a rush. It had taken 9 months. They then set out to tow her to Lyness and she stuck fast: one of her 11–inch guns had snagged on the seabed. Divers went down and the barrel was blown off, and the next day she was beached. The workers set about stripping off as much marine growth as possible and then taking everything removable out of the hull to lighten it before towing her to the breakers, removing some 3,000 tons. In May 1928 she was as ready for sea as she ever could be.

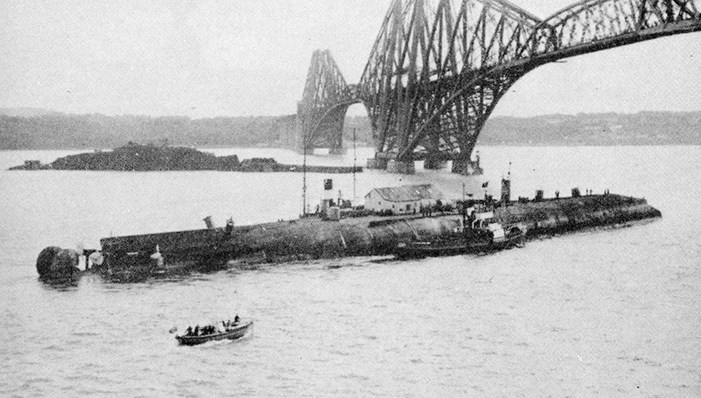

The task of towing an upside–down battleship out of Scapa Flow and down the east coast of Scotland to Rosyth, a distance of about 275 miles was awarded, with no doubt unconscious irony, to a German firm, which supplied three ocean–going tugs. The long air–locks had been replaced with shorter ones and two corrugated iron sheds had been constructed on the keel, one for the pumps to maintain air pressure in the hull, and the other to serve as a bunkhouse for the fourteen men whose job it was to keep her afloat. Lifeboats and rafts were attached, a galley and bunks installed and on 18 May 1928 the exhumed battleship began her last, posthumous, journey. Inevitably, a gale blew up on the open sea, and as she wallowed helplessly in the rough water compressed air escaped. The powerful tugs could not make headway against the fierce wind and the little convoy was blown backwards for a while, dragged by the leviathan of the wreck, which sank six feet in the storm. Once it had blown over, more air was pumped into the hull. They reached the Firth of Forth without further incident.

Lucky ship

Here a civilian pilot boarded the leading tug to bring the tow safely up the Forth. Shortly afterwards an Admiralty pilot went aboard, and a protracted jurisdictional dispute ensued. It was a clash between two bureaucratic prima donnas about who was responsible for a civilian operation which was bringing a German wreck to a Royal Naval dockyard for breaking up. As the words steamed up the windows, the tow lines slackened. Moltke began quietly to gain on her escorts propelled by the incoming tide. In the middle of the Firth of Forth is the islet of Inchgarvie, dividing the waterway in the approaches to the great railway bridge. With the tow lines slack and the impasse between the two pilots rising to new heights of vituperation, nobody initially seemed to notice that the tug in the lead was sailing past one side of the island while the drifting hulk was floating past the other. Horrified and helpless, the tug’s crew cut the tow as it snagged the island. Ahead lay the Forth Bridge, one of the great engineering triumphs of the Victorian age. Now a floating island of more than 20,000 tons of the best German steel was drifting inexorably towards the central spans of the long bridge, completely out of any control. The petulant pilots and the trembling tugboat men, to say nothing of the accompanying Cox, watched impotently as the inverted hulk silently bore down on the bridge. Cox, no doubt, found time to reflect on his insurance policy taken out to cover the Moltke: the insurers had refused to cover more than two thirds of any loss. By some miracle and much against the odds, the erstwhile ‘lucky ship of the German Navy’ drifted between the two piers of the bridge without touching them. The tugs took her in tow again and brought her into Rosyth. There was a further difficulty in getting her into a dry dock, eventually overcome, and finally Cox could celebrate. The Alloa Shipbuilding Company took over the ship from Cox & Danks to cut her up for scrap.

Raising the rest

The von Der Tann passing beneath the Forth Bridge on its way to the breaker’s yards at Rosyth. The island of Inchgarvie is in the background

Back at Scapa, Cox next raised the Seydlitz on 1 November 1929 and despatched her to Rosyth in May 1930. Then the Kaiser came up easily at the first attempt, followed by the light cruiser Bremse and the battlecruiser Von der Tann. Cox went back to the Hindenburg in the summer of 1930 and she was successfully raised and beached in July. As work began on gutting her Mrs McKenzie, wife of Cox’s chief salvage officer, took up the pleasant if eccentric habit of installing herself every day in the crow’s–nest to knit or read a book. She only gave up this habit when the jib of a crane struck the mast and nearly severed it. In August Hindenburg was towed to Rosyth without incident, the largest ship ever to be salvaged. Prinzregent Luitpold came to the surface like a lamb in July 1931 and went to Rosyth in May 1932.

In 1932 Cox withdrew from Scapa handing over his interest to the Alloa Shipbreaking Co., which had been buying the wrecks from Cox. In the course of the years 1933–38 they raised Bayern, Grosser Kürfurst, Konig Albert, Kaiserin and Friedrich der Grosse. Finally, the Derfflinger was raised from the greatest depth ever, 150 feet, in July 1939.

The last to be broken: SMS Derfflinger being towed to Faslane in a floating dock

There was no time to tow her to Rosyth before the war started and so she spent the entire war moored upside down next to HMS Iron Duke – ironically Jellicoe’s flagship at Jutland, and, throughout the Second World War, the guardship at Scapa Flow. Still afloat in 1946, Derfflinger was towed not to Rosyth but to the Clyde, and proved to be the last ship of the High Seas Fleet to be raised from the bottom. She was towed upside down, as all but the Hindenburg and the Baden were, but this time in a floating dock. At Faslane Port she was the last German ship to be broken up.

The scrap metal was used for many purposes and was sold all round the world. Krupp of Essen, who had made much of the armour plate originally, bought back some of their own handiwork and used it to help build Hitler’s navy. It is entirely possible, therefore, that elements of the High Seas Fleet were scuttled twice: in 1919 and again in 1939 when the pocket battleship Graf Spee was scuttled after the Battle of the River Plate. Recovery work at Scapa has never ceased because of two words, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. From the time of the atomic explosions in 1945 the earth’s atmosphere has been polluted by an unnaturally high quantity of nuclear radiation. When making steel, enormous quantities of air are sucked in and blown through the molten iron, and therefore all steel made after 1945 contains significant traces of radiation. When it comes to the manufacture of certain delicate scientific instruments, notably devices used to measure or screen radiation, untainted steel is essential. Scapa Flow remains the largest accessible source of uncontaminated steel on the earth. It is accepted on Orkney that some of the metal has been used in the American space programme, although NASA will neither confirm or deny it.

A visit to Scapa Flow is definitely worthwhile if you can get as far as that.

A book on the scuttling by Nick Jellicoe, grandson of Admiral Lord Jellicoe, C–in–C of the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland – The Last Days of the High Seas Fleet: From Mutiny to Scapa Flow – is in preparation.

References

(1) Arthur Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Volume 5, 1918–1919: Victory and Aftermath, (OUP: 1970), pp.332–3.

(2) Captain J D Munro, Scapa Flow: A Naval Retrospect, (Sampson Low: 1932), p.225. It is interesting to note that both proverb and the use of the word ‘Jack’ to describe a sailor, date from 1659.

(3) War Cabinet, 19 October 1919.

(4) Wemyss to Beatty, 5 November 1918. The Beatty Papers, Volume 1, (Navy Records Society: 1989), pp.559–560.

(5) The full terms are to be found in Sir Henry Newbolt, Naval Operations, Volume 5, Appendix D, (Longmans: 1931), pp.413–418.

(6) Wemyss to Beatty, 12/13 November, The Beatty Papers, Volume 2, (Navy Records Society: 1993), p.13.

(7) Quoted in Dan Van der Vat, The Grand Scuttle, (Waterfront Communications: 1968), p.129, from Reuter’s report after his return to Germany in 1920.

(8) Vice Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, Scapa Flow: the Account of the Greatest Scuttling of All Time, (Ian Allan: 1940).

(9) Katie Watt, aged 18 in 1919, quoted in Dan Van der Vat, op.cit., pp.172–173.

(10) Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Fight of the Revenge, 1878, stanza 11. However, it is worth pointing out that Grenville’s officers did not fall in with his views and persuaded Grenville to surrender with honour to the Spaniards, although he died that day. The battered and barely afloat Revenge sank two days later in a storm.

(11) Quoted in Van der Vat, op.cit., p.199.

(12) Gerald Bowman, The Man who Bought a Navy, (Harrap: 1964).

Sources

Gerald Bowman, The Man who Bought a Navy, (Harrap: 1964).

S C George, Jutland to Junkyard, (Patrick Stephens: 1973).

Arthur J Marder, From the Dreadnought To Scapa Flow, Volume 5, 1918–1919, Victory and Aftermath, (OUP: 1970).

Sir Henry Newbolt, Naval Operations, Volume 5, (Longmans: 1931).

B L Ranft, The Beatty Papers, Volumes 1 and 2, (Navy Records Society: 1989 & 1993).

Ludwig von Reuter, Scapa Flow: the Account of the Greatest Scuttling of all Time, (Ian Allan: 1940).

Friedrich Ruge, Scapa Flow 1919: the End of the German Fleet, (Ian Allan: 1973).

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Complete Works, (Macmillan: 1915).

Dan van der Vat, The Grand Scuttle, (Waterfront Communications: 1968).