Death of a Princess : The Destruction of HMS Princess Irene 27 May 1915

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Death of a Princess : The Destruction of HMS Princess Irene 27 May 1915

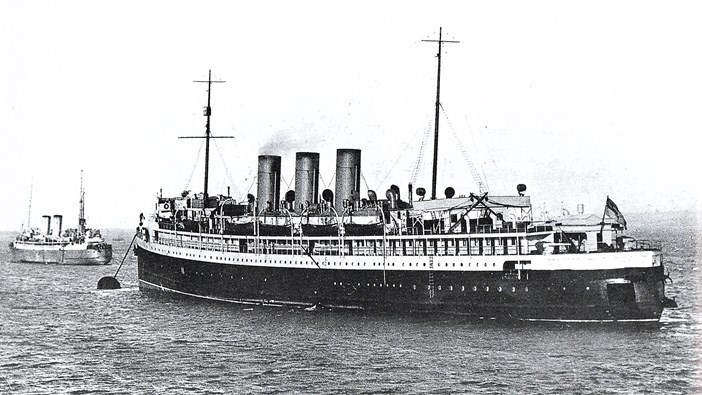

In May 1913 the Canadian Pacific Railway had placed an order with Denny’s of Dumbarton for two new ships for their route on the Pacific coast between Vancouver, Victoria and Seattle. The ships were elegant and well appointed three-funnelled vessels 350 feet long with a 54 foot beam and displacing 5,500 tons. Oil-fuelled boilers drove two propellers via steam turbines to give a maximum speed of over 23 knots.

The first of the ships, the Princess Margaret, was launched on the 24 June 1914 and, following fitting out and completion of sea trials, she was ready for delivery on 15 November. The owners had planned to sail her round Cape Horn to Vancouver, however, there were concerns about German warships in the Southern Ocean; the Battle of Coronel having been fought two weeks earlier. Consequently, the delivery voyage was postponed.

Her sister ship the Princess Irene was launched on 20 October 1914 and there was talk of the Princess Margaret awaiting her completion before they sailed to Vancouver together.

The Royal Navy was meanwhile coming to terms with a relatively new facet of warfare – mines. As the war progressed, they first laid defensive minefields off Britain’s coast to try and deter German raiders from bombarding coastal towns, and then they looked at laying offensive minefields off the coast of Europe to help enforce the blockade on Germany. They realised that if they had fast mine-laying ships they could cross the North Sea at high speed late in the day, lay their mines unseen at night, and be heading back to friendly waters before daylight.

Consequently, they looked for suitable vessels and the two Canadian princesses were amongst those requisitioned. They were stripped of all their fittings such as wooden panelling, before stowage for more than 400 mines, the mine launching rails and defensive guns were installed. The Princess Irene was delivered to the Royal Navy on 26 January 1915 and after conversion left the Clyde for her new base at Sheerness, Kent, on 18 March.

Above: Princess Irene after conversion. One of the ports cut in her stern for dropping the mines from can be seen. (Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, PSMHA 6865)

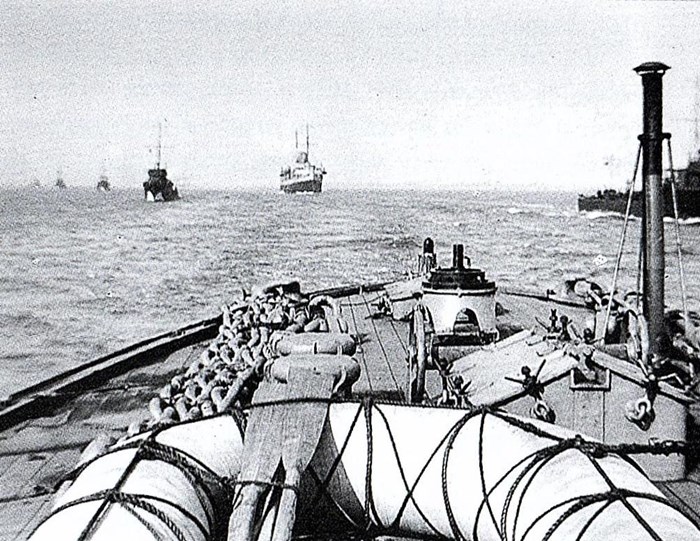

Under the command of Captain Mervyn Cobbe, and with a crew of 225 officers and ratings, she carried out her first operation in late April when she laid 280 mines in the English Channel. In early May she then carried out a second operation laying mines north-west of Heligoland, before returning safely to Sheerness.

Above: Captain Mervyn Cobbe. (IWM HU120109)

Above: Photograph of the Princess Irene returning from her second minelaying operation. (National Maritime Museum, N22793)

On 25 May the Princess Irene was moved from moorings near Sheerness Dockyard to a quiet anchorage in Saltpan Reach, in preparation for another operation. A new load of mines was feried out to her in barges, with loading starting on the morning of the 26th when each of the mines was lifted aboard and stowed on the rails.

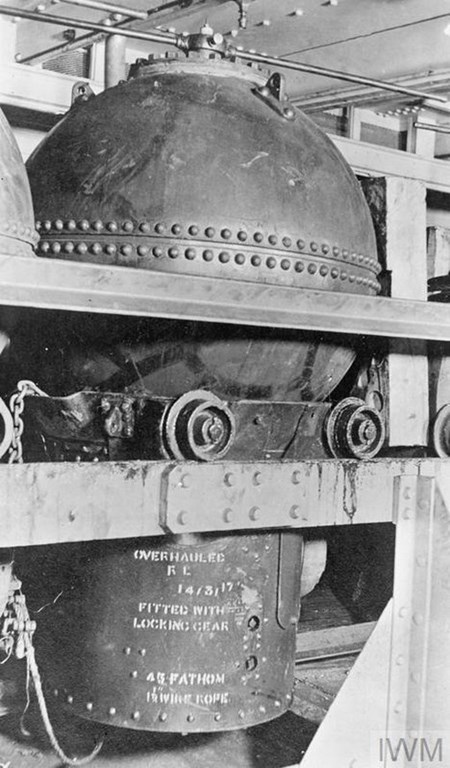

Above: A mine stowed on rails between decks. (IWMQ52968)

Once all the mines were loaded and secured the task of priming them was begun. To do this a cover plate was removed and the detonator and primer were fitted. At the time the navy used the Heneage pistol that required the striker pin to be ‘cocked’ by a compression spring before inserting into the mine. There were inherent dangers with this type of pistol and so the task of cocking and fitting them should only have been entrusted to well-trained and experienced men. The navy, knowing of problems with this type of pistol, was at the time in the process of introducing an improved design.

The morning of 27 May 1915 saw a hive of activity on and around the Princess Irene. At about 7 a.m. a party of Sheerness Dockyard workers arrived, as they had been doing for the previous three weeks, to complete work on increasing the Princess Irene’s mine carrying capacity and strengthening her decks. Also on board were 89 men from Chatham Dockyard to help with priming the mines.

At about 9.15 a.m. three of the Princess Irene’s crew went ashore, one was the ship’s postman going to collect the mail, and another was probably not really looking forward to a visit to the dentist! At 11.10 a.m. Mr Quint, who was in charge of the refit work, left the Princess Irene with five men who had been onboard removing slings for testing ashore.

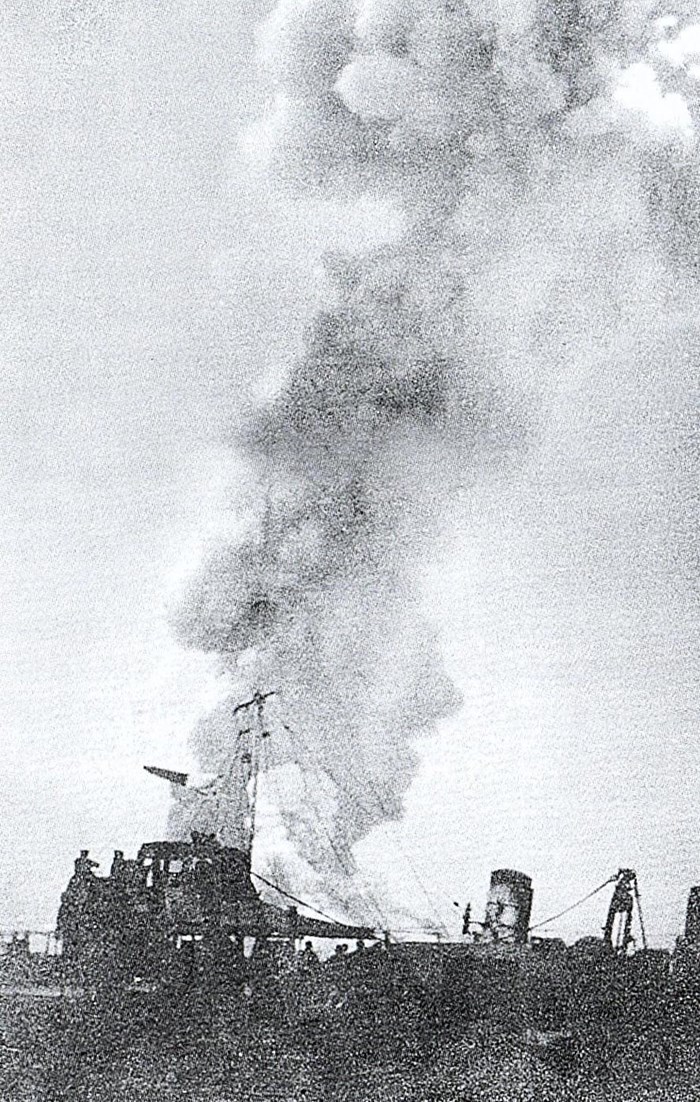

Four minutes later disaster struck. The Princess Irene was enveloped by an enormous explosion, likened by one witness to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Where a few seconds earlier an elegant new ship had been bobbing peacefully at her moorings, there was now just a column of flames, smoke and debris rising high into the sky. Another witness described how the Princess Irene seemed to be hurled into the air a mile high in 10,000 fragments, and how he could make out the forms of men amidst the flying wreckage.

Above: A plume of smoke rises high into the sky shortly after the Princess Irene blew up. (The National Archives, ADM 1/8422/147)

The buildings in Sheerness three miles away shook in the blast wave, and debris rained from the sky. On the Isle of Grain four of the navy’s oil storage tanks were ruptured and the pumping station and main pipeline damaged by pieces of the ship’s side falling on them.

In Grain village, nine year-old Hilda Johnson was killed in her uncle’s garden when she was stuck by a piece of wreckage, and in the fields nearby 47 year-old farm labourer George Bradley dropped dead from the shock. Others onboard nearby ships were injured and on a coaling ship, about half a mile from the Princess Irene, a large piece of steel plate killed a crewman, two others were injured and a deck crane was toppled by a section of ship’s boiler falling onto the deck.

Debris landed for miles around and lighter objects were reported as being found at Detling, 11 miles away. The police had to ask residents in a wide area to conduct searches of their properties for debris and human remains, while farm workers were enlisted to search the local orchards and fields for body parts.

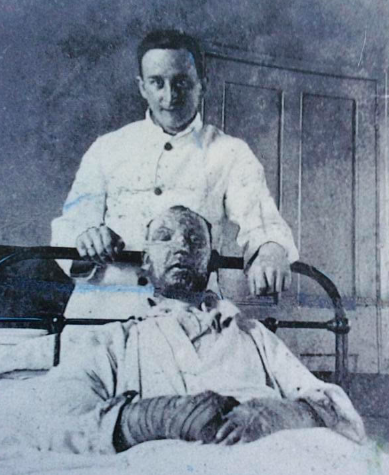

The explosion killed more than 380 men on board. All of the Princess Irene’s crew except for the three men ashore perished; all the Sheerness Dockyard workers, except Mr Quint and the five men who had just left the ship died. All the Chatham Dockyard workers were also killed except for one extremely lucky man, Stoker David Wills, who was going for an early lunch in the forward galley at the time of the explosion. He was spotted struggling in the water amongst the oil and wreckage and rescued by the crew of a nearby tug. He suffered severe burns to his face, arms and hands but, after a long convalescence, was passed fit to resume service and remained in the Navy for a further 12 years. He named one of his daughters Irene after the ill-fated ship.

Above: Survivor David Wills pictured in hospital. The HMS Princess Irene Disaster (c) Rainham History

The navy launched an inquiry and could only conclude that a faulty pistol probably set off a mine as it was being fitted causing an initial explosion that set off a chain reaction destroying the ship and her crew. Evidence from men who had primed mines on other occasions revealed that, due to the pressure of time, less than fully experienced men had sometimes been employed to assist with the priming; also a defective pistol was produced to show how one could cause the detonation of a mine during fitting. The conclusion was that ‘under the lamentable circumstances, the Court consider it is impossible to attribute blame but it is of the opinion that no plea of haste should ever allow these pistols being fitted by other than fully qualified men and further that a slight mechanical device should be fitted to the pistols to ensure that the pistol could not fire until it is properly placed with other safety devices in the mine’.

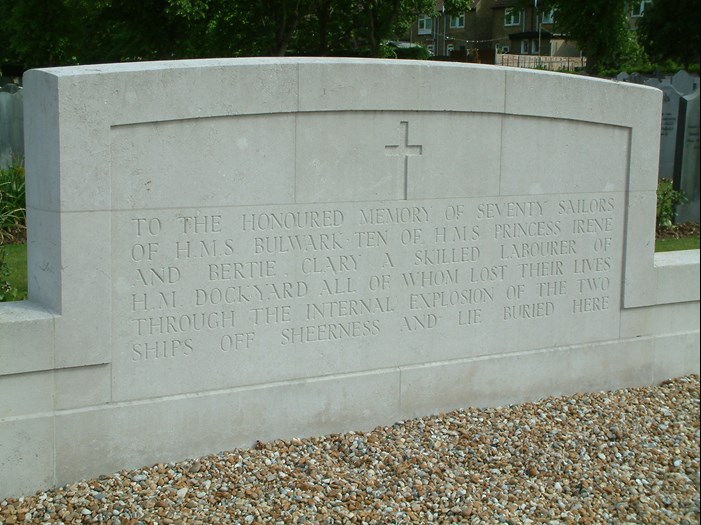

The remains of 15 sailors that could be identified were buried in Gillingham’s (Woodlands) Cemetery. Unidentified remains of another 10 were interred in a mass grave that had originally been dug for 70 men of HMS Bulwark that had blown up six months earlier. Skilled Dockyard Labourer, Bertie Clary, was also interred in the mass grave.

Two of those lost on the Princess Irene came from Moray in the north of Scotland. Sub Lieutenant Alexander Paterson was born in Lossiemouth in October 1886, the son of William and Bessie Paterson who lived at Stotfield. In 1901, the local newspaper reported that Alexander had received a presentation for 7 years perfect attendance at school. By 1911, Alexander was living and working in Glasgow as a marine engineer. He enlisted in March 1915 - just ten weeks before his death on the Princess Irene. The obituary in the Northern Scot stated ‘a peculiar tribute of lamentation seems due to young Paterson sent to his death by an appalling and mysterious accident’. The second Moray man, Alexander Jamieson was born in Rathven in March 1888. He had served in the Royal Navy and had lived in Glasgow.

Above: Sub Lt Alexander Paterson and Greaser Alexander Jamieson.

Surgeon Frederick Whitby Quirk was born in Kensington in 1885 and had served as a Surgeon in the Navy since 1908.

Above: Surgeon Frederick Quirk – another casualty of the Princess Irene © IWM HU 117302

James Golden was born in Kent in 1887. He served on the ship as a leading Stoker.

Above:Leading Stoker James Golden. Lives of the First World War from Families of Wartime contributed by Bearsted3394 CC BY SA 2.0 IWM

Above: The mass grave in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery for victims of the Bulwark and Princess Irene explosions.(Photo - Derek Bird)

Amongst the victims of the Princess Irene explosion buried in Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery is 18 year-old, Ordinary Signalman, Frederick Timms. (Photo - Derek Bird)

The missing naval men are commemorated on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, while the Sheerness war memorial commemorates all the men lost on the Bulwark and Princess Irene, a total of 1,070 souls. One of the side panels is largely made up of the names the local dockyard workers who perished in the Princess Irene explosion.

Above: Sheerness war memorial (Photo - Derek Bird)

Above: Sheerness war memorial commemorates the 1070 men lost on the Bulwark and Princess Irene. (Photo - Derek Bird)

Above: Sheerness war memorial also commemorates the 76 local dockyard workers killed on the Princess Irene.(Photo - Derek Bird)

Although some wreckage was lifted from the seabed in the 1960s after a tug fouled an obstruction off the Isle of Grain Oil Refinery (since replaced by the Thamesport Container Terminal), a significant portion of the Princess Irene remains on the seabed. Unless the port authority needs to open up the navigation further there is a reluctance to disturb the wreckage as there may still be unexploded mines from that fateful day in May 1915.

Article by Derek Bird

Further reading

Blown to Eternity: The Princess Irene Story by John Hendy, Ferry Publications 2001. ISBN 1-871947-61-8.