New Year's Day 1915: The unknown 'Battle of Broken Hill'

- Home

- World War I Articles

- New Year's Day 1915: The unknown 'Battle of Broken Hill'

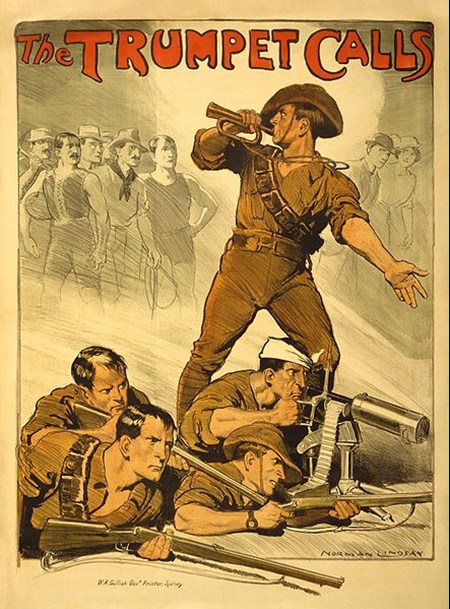

Whilst the vast majority of First World War actions took place in France and Belgium, there were other theatres of war in which British and Commonwealth soldiers and sailors fought. These so called ‘side shows’ in obscure theatres of war took place in many different countries, from Turkey (the Gallipoli Campaign) to off the coast of Chile (the Battle of Coronel), from Ireland to East Africa. But the ‘battle’ that took place on New Year’s Day 1915 in Broken Hill, New South Wales, Australia was unexpected and the first (and possibly only) incident of the First World War involving Australian civilians. This attack, which would probably be described as a terrorist incident today, was linked to Britain’s (and by extension Australia’s) declaration of war on Turkey which occurred on 5 November 1914.

As Dr Peter Stanley has written in a BBC History Article:

“With the outbreak of war the new Commonwealth of Australia found itself willingly at war for the empire. Australian leaders were not consulted, but demonstrated their unqualified loyalty. Andrew Fisher, Labour prime minister from 1914 to 1916, declared that Australia would support Britain to 'the last man and the last shilling'.”

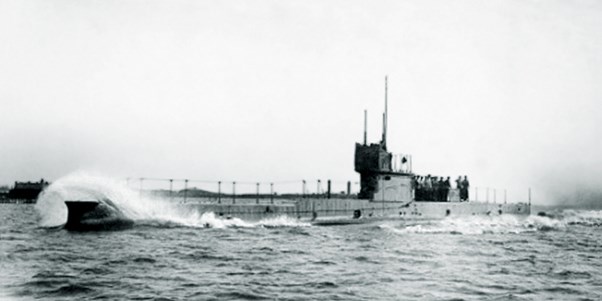

Australia had declared war on Germany, alongside Britain, on 4 August 1914, and had not been involved action other than the occupation of German New Guinea which resulted in no more than six fatalities (these are buried at Rabaul (Bita Paka) War Cemetery). The only other incident which caused an early loss of life to Australians in 1914 was the sinking of her first submarine, the AE1 which was lost with all hands on 14 September 1914. The 35 men who were drowned in this accident are commemorated on the Plymouth Naval Memorial.

HMAS AE1.

New Year’s Day

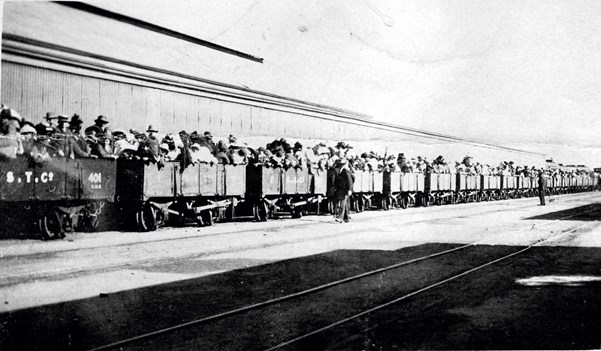

1 January 1915 was a holiday for the mining community of Broken Hill. It was the height of the southern summer and about 1,200 men, women and children were looking forward to a picnic organised by the Manchester Unity Order of Oddfellows. They were to take a train the 15 or so miles from Broken Hill towards Silverton. Unbeknown to the miners and their families, two men had, for varying reasons, prepared an ambush.

Sulphide Street railway station, Broken Hill, NSW Australia.

Gool Mohammed, an Afghan cameleer who had fallen out of work and who now sold ice-cream in Broken Hill and Mullah Abullah (another Afghan who was the butcher for the local camel-drivers) were laying in wait. Relations between the Afghan camel-drivers and Australians had deteriorated in the years before the war; there are reports of the Afghan camps being raided and the camels being deliberately injured. Fights between the two groups were often seen and there were also at least six murders committed a result of these disputes.

Gool Mohammed had served in the Turkish Army in the early 1900s and, learning of the outbreak of war, had written to the Turkish Minister of War in Istanbul, offering to re-enlist. Surprisingly, not only had his letter been delivered, but he had also received a reply which instructed him to “be a member of the Turkish Army and fight only for the Sultan”. Thus encouraged, but unable to return to Turkey, Gool Mohammed probably started making plans for a direct form of action. The edict from the Sultan in November 1914 calling for the Islamic world to support the Ottoman (and German) cause no doubt encouraged him further.

Mullah Abdullah had been born in 1855 and had arrived in Australia in about 1899. He was the spiritual head of a group of cameleers and led the daily prayers, presided at burials, and killed animals for food consumption using the traditional halal method. However, the butchering of animals was a job that could only be done by members of a trade union, and because was not a member of the union, he had been fined by the local chief sanitary inspector, a Mr Brosnan, for slaughtering sheep on unlicensed premises. It is likely that Gool Mohammed used this as a lever to persuade Mullah Abdullah to take part in the scheme.

Ambush

As the train, comprising forty open carriages, pulled up a hill two miles outside Broken Hill, it came into sight of the two men at 10.10 am. Gool Mohammed and Mullah Abdullah opened fire. The occupants were badly exposed as the carriages were simply flat bottomed, open wagons with benches for the passengers to sit on.

Passengers on the Broken Hill picnic train, c. 1915. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia.

Gool Mohammed and Mullah Abdullah discharged only half their ammunition rounds (they were wearing homemade bandoliers containing 48 cartridges) into the picnic train. Despite being within easy range, only ten passengers were hit, three of whom were killed, including a seventeen year old girl who had joined the trip with her boyfriend. As the train slowly pulled out of range, a couple of passengers jumped from the train and started back into Broken Hill to raise the alarm.

Elma Cowie (aged 17) had joined the trip with her boyfriend

The train pulled into a siding and the local police were telephoned. The police contacted Lieutenant Resch at the local army base who despatched some of his men, and the two groups jumped into a couple of cars. The operation did not go smoothly, one of the cars broke down, and everyone crowded onto the other car.

The Broken Hill picnic train, packed with 1,200 holidaymakers, that was ambushed on January 1, 1915. (Smithsonian.com)

In the meantime, Mohammed and Abdullah had moved away from their original ambush position and started to head back towards their camp. On the way they came across a hut where Alfred Millar had taken barricaded himself. He, too, was shot dead. The pursuing police came across the two men but, not knowing if they were the attackers, fired over their heads. Any doubt was eliminated when fire was returned, injuring a police officer. Mohammed and Abdullah headed for some rocks and took cover. The police and army personnel were unable to approach the cover without drawing fire so resorted to taking shots at the outcrop where the attackers had taken cover. In the mean time the gun battle not surprisingly drew the attention of the locals, who, learning what was going on, seized a number of weapons from a nearby rifle club and joined in.

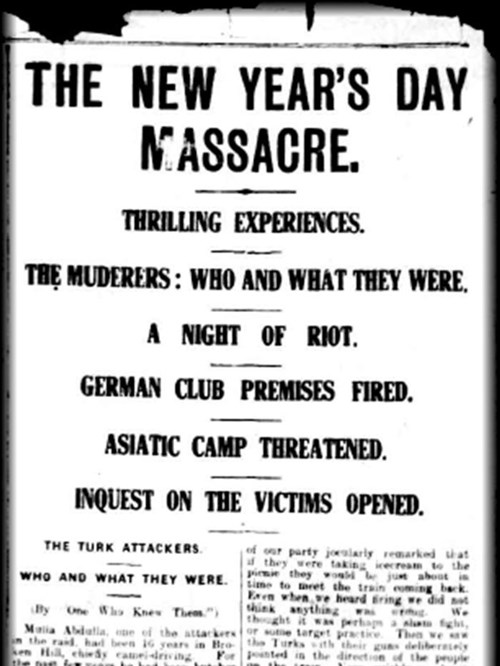

The local newspaper, the Barrier Miner, described the gun battle in its edition on the following day, 2nd January, 1915

The general operations were under the direction of Inspector Miller and Lieutenant Resch. The attacking party spread out on the adjoining hills, and there was a hot fire poured into the enemy's position, the Turks [sic] returning the fire with spirit but without effect, which is rather surprising, as the range was short, and the attacking parties in some cases exposed themselves rather rashly in their efforts to get a shot.

Headline from the Barrier Miner newspaper the day after the massacre

Unperturbed by the firing, a local man continued chopping wood just 500 yards from the battle. His blasé attitude was his downfall, he was killed by a stray bullet. The Barrier Miner again:

The attacking party was being constantly reinforced by eager men, who arrived in any vehicles they could obtain or on foot. At just about one o'clock a rush took place to the Turks [sic] stronghold, and they were found lying on the ground behind their shelter. Both had many wounds, One was dead, the other expired at the Hospital later.

Part of the rocky outcrop where the final battle took place

Aftermath

Immediately after the attack, it was rumoured that the local German community must have been behind the ambush, and as a result the local German Club was set on fire, when the fire brigade arrived, they found themselves fighting the crowd (who tried to cut the hoses) as well as fighting the flames. After the fire at the German Club had been extinguished the crowd marched to the Afghan camel camp. Their way was barred by the local militia and the Police who stood guard all night.

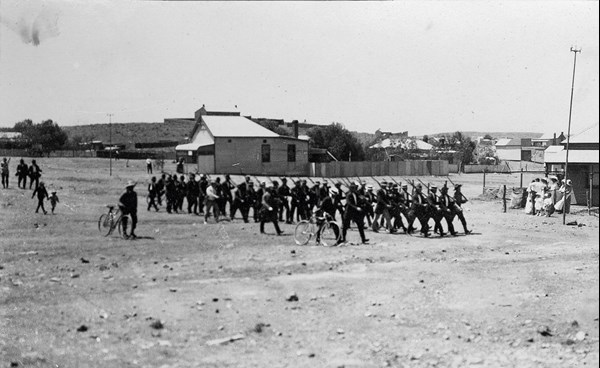

Returning to Broken Hill after the attack, 1 January 1915. Image courtesy of the State Library of South Australia.

Gradually Broken Hill returned to normal. The Silverton Tramway Company refunded in full the fares for the picnic train and the money was used to launch a public relief fund. Less honourable was the request that had to be made for the return of the rifles “borrowed” from the local gun club.

The rest of the war

The events at Broken Hill were a precursor to the conflict in which Australia was about to find itself. The CWGC database records just over 62,000 fatalities from Australia’s forces who were killed in the Great War with nearly 61,500 of these having served in the Australian Imperial Force (the AIF – the expeditionary force of the Australian Army). None of these fatalities were as a result of the Battle at Broken Hill. It is possible that these events on New Year’s Day, 1915 re-doubled the recruitment into the AIF, which remained an all-volunteer force throughout the war.

Men at the recruiting office at the Town Hall, Melbourne, to enlist for service in World War 1

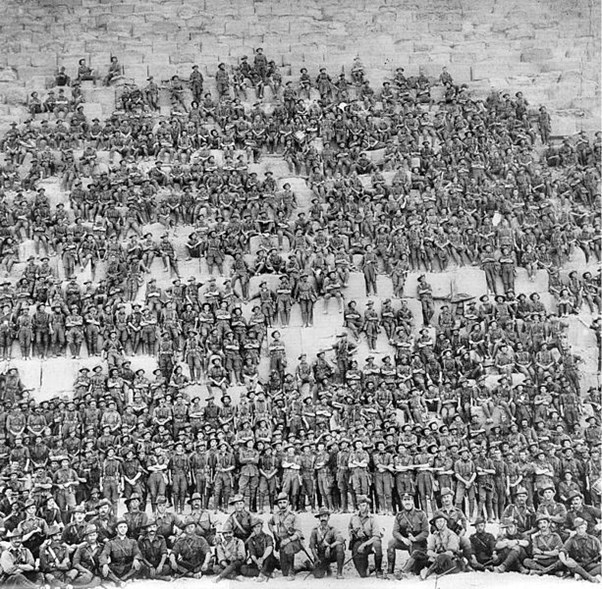

The story of the AIF is well known, with the men of the first AIF (who became well known as ANZACs) being sent initially to Egypt and then to Gallipoli where the legend of the ‘diggers’ was born. This was followed by the prolonged service on the Western Front where again the prowess of the Australian troops became highly regarded. They were renowned as tough, but difficult to discipline, fighters.

Group portrait of the Australian 11th (Western Australia) Battalion, 3rd Infantry Brigade, Australian Imperial Force posing on the Great Pyramid of Giza on 10 January 1915, prior to the landing at Gallipoli. The 11th Battalion did much of their war training in Egypt and would be amongst the first to land at Anzac Cove on April 25 1915. In the five days following the landing, the battalion suffered 378 casualties, over one third of its strength.

Broken Hill today

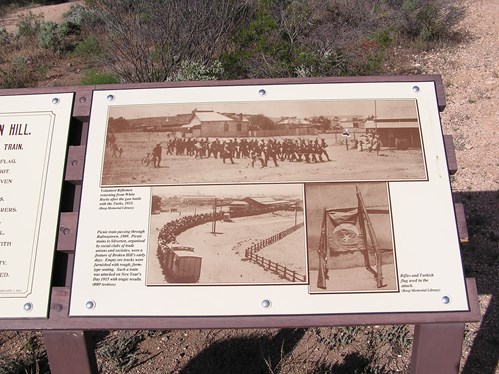

Broken Hill is Australia's longest-lived mining city, but there is little to mark the events of New Year’s Day 1915. The White Rocks Historical Site has a number of historical information boards. The photographs below are courtesy of Gareth Morgan, President of the Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians. My thanks to Gareth for drawing my attention to this ‘battle’.

Left: A reconstruction of the ice-cream cart that Gool Mohammed used in 1914. / Right: One of a series of orientation boards at the site

Article by David Tattersfield

Further resources:

Continuing with the ANZAC theme, why not watch John Bourne on the WFA's YouTube channel talk about Gallipoli - the faded vision