'One Hell of a Row': A War widow's pension

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'One Hell of a Row': A War widow's pension

Grandfather was killed 7 weeks before the end of the First World War. His immediate family, that is his wife and three sons, never knew how nor where. Neither did they know he was commemorated on Panel 5 of the Memorial Wall at Tyne Cot Cemetery. This we had from two of his sons, our Father and his brother, our Uncle Tom. Towards the end of the1970s, Father asked that a belated attempt be made to discover the circumstances of his Father’s death. The preliminary results of that attempt were published in two articles in Stand To!, in 1987 and 1989, the conclusion reached then was that Grandfather had been died at English Wood, near Café Belge and Dickebusch, where his artillery unit was preparing a gun site prior to the assault that broke through the German Lines on the Ypres Salient five days later. Although this conclusion appeared supposition and circumstantial, there was documented evidence for it. Even so it was not definitive. Neither of us was satisfied, even though we believed we had identified where Grandfather was buried, in the grave of a soldier ‘Known unto God’, at the Klein-Vierstraat Cemetery.

Our Research, we called it ‘search’, continued. In the end we had gathered enough information for the local branch of the Western Front Association (hereafter WFA) to help us have Grandfather’s name added to the War Memorial in Crewe, the town where he had enlisted. The ceremony took place on Remembrance Sunday 2004, weeks before Father died. Even then, we did not stop. More information came to light, some of which is drawn upon in this article. We now have a comprehensive knowledge of Grandfather’s life, including his service in the Boer War as well as the First World War, but until recently two issues remained unresolved.1

In putting together the story of his life, we had had to depend, in small part, on Oral History, namely what our Father and Uncle told us. Oral History, being memory, is notoriously unreliably, and so it proved to be in our case. For example, on one occasion, when we revisited Uncle Tom in hospital, he denied vehemently the information he had given us the week before and we had written down. Similarly, Father talked of a fob watch given to his Father in 1913, by a relative who had emigrated to the U.S.A. When a watch was found fitting the description of the one about which he had talked, he immediately identified it as the one his Father had proudly worn, only to deny he knew anything about it when he saw it again sometime later.2 Despite this, Father repeatedly made one statement he never changed, right up to his death at the age of 98. There had been, he insisted, ‘one hell of a row’ (his words) over his Mother’s War Widow’s Pension, and he wanted to know ‘what that was all about’ (his words again). He gave the impression he was more interested in that row than he was in the circumstances of his Father’s death.

That mystery tied in with another. The official Notice of Death sent to Grandmother described her husband as Gunner, as did all the other documents she later received; as did the Memorial Card she had published; as does his commemoration at Tyne Cot. But Grandfather had been a Sergeant. He was a Boer War veteran. Describing himself as a ‘labourer’ when he enlisted in 1898, according to his Savings and Account Book and his Account Book or Pocket Ledger, both still extant along with his South African War medals, he passed successive examinations during his subsequence service, so that by the time he bought himself out in October 1902, he had been progressively promoted to Sergeant.3 It is also true that in 1914-15, experienced NCOs were amongst much else Kitchener’s volunteer army lacked.4 The probability has to be that, when Grandfather enlisted in October 1915, he was soon restored to his Boer War rank. Indeed one of his First World War Medals is engraved, ‘Sergt. E. N. Lea’. Was it possible then that he had been demoted during the War? Was there a row over Grandmother’s pension, because it did not take into account her husband’s rank for most, or at least some, of the duration?

For years, we did not know the answer of these questions, not least because a trawl of demotions in the Home and Field Court Martial records, in the Public Records Office (as it was then), found no reference to any E. N. Lea. The weight of available documented evidence had to be that Grandfather had never been an NCO in the 1914-18 War, but…?

A reference to a War Pension Service, on the WFA website, caught our attention. It was the first time we had come across any suggestion that World War 1 pension records may have survived. We had assumed they had gone the same way as soldiers’ personal records, Grandfather’s not being amongst the rescued so-called ‘Burnt Papers’. We submitted an application to the WFA’s Pension Service for a search to be made, duly paid up, and thanks to the remarkable efforts of the project’s meticulous director, David Tattersfield, both unanswered questions have been answered. Grandfather was not demoted, because he was not promoted. The ‘row’ that so occupied Father was about something else.

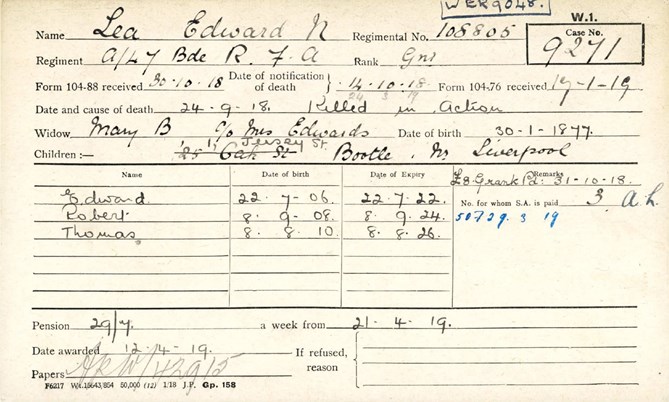

David Tattersfield sent us a photocopy of this Pension Record Card:-

The significance of this card lies in the chronology to which it contributes:-

23 September1918 Grandfather died on 23 September 1918. The War Diary of his Royal Field Artillery Brigade (hereafter RFA), the 47 Brigade in the 14th (Light) Division, records on that Monday, ‘A/47 had 1 O.R. killed’. That OR was Grandfather, for he served in the Brigade’s A Battery, and it is consistent with other Divisional records of that day and the day after.

24 September 1918 The casualty was officially recorded and remained attributed to this date on all subsequent documentation. The discrepancy is explained by the fact that, for the military on active service at that time, the day started and ended at 06.00 hours. News of Grandfather’s death did not reach and was not recorded at the Brigade’s Headquarters until after the start of the next official day, the HQ being at Rattekot Inn, a night’s march away from the gun site A Battery was preparing at English Wood.5

2 October 1918 On this Wednesday, Second Lieutenant Poole-Smith, the CO of Grandfather’s Section in A Battery, wrote to Grandmother, offering her condolences on her husband’s death. Thanks to the Army Postal Services, his letter is likely to have been delivered in less than a week. The envelope has not survived. This was the first news Grandfather’s family had of his fatality. 70 years later, Uncle Tom (aged 8 in 1918) recalled the letter incorrectly; Father (aged 12 in 1918) had no memory of it at all. Poole-Smith’s delay in writing was caused by his Brigade preparing for a second advanced and attack, after it had contributed to the initial breaking through on the Salient.

14 October 1918 The RH & RFA Records Office, Woolwich, sent Army Form B 104-82 to Grandmother, stating a report had been received from the War Office on the KiA death. Presumably this was the infamous ‘Telegram’. If it was, it must have been received on the same day, or certainly the day after. Apart from this assumption, the date of its receipt is not known.

30 October 1918 The Ministry of Pensions, according to the Pension Record Card, received Army Form 104-88, a form of unknown purpose, but likely to be related to Army Form B 104-82, sent to Grandmother. An administrative duplicate?

7 November 1918 The Ministry of Pensions sent a formal printed letter to Grandmother, informing her of an unspecified preliminary amount she was to receive in recognition of her bereavement. Strangely, where the amount to be paid should have been entered, there is a blank space. This cannot be because the ink has faded over the years, for a handwritten £-sign, in ink, remains perfectly legible. The obvious inference is that she was sent nothing. In which case why was the letter sent?

19 January 1919 The Pensions Office received Army Form 104-76, which, according to the Pension Record Card, appears to be related in some way to the Official notification of death sent to the widow on 14 October, the actual death having occurred all but three months earlier. Even if this Form served some other purpose, it clearly indicated that the administrative process could not proceed until it had been received by the Pensions Office.

12 April 1919 A decision was made to award Grandmother a pension of 29/7 (29 shillings and 7 pence, or 1 Pound, 9 shillings and 7 pence). 6

21 April1919 Over a week later, Grandmother was able to claim her first pension payment. From the date of the death to that payment, there had been a lapse of seven months (less two days). From the date of the receipt of the Section CO’s letter, seven months less two weeks had passed.

Was this delay, these months, this more than half a year in which no pension was received, the cause of the ‘row’ Father remembered in his old age? Had forcefully expressed disgust at the treatment his bereaved Mother received been heard and noted by an impressionable 12 year old lad, who himself grieved the loss of the Father he idolised, and with whom he had had so much fun, including setting off fireworks in bundles of three?

Edward ('Ted') Lea poses for a formal studio photograph with his wife Polly and their children (left to right) Robert, Thomas, and Edward, the father of authors John and David Lea. Courtesy John and David Lea / Liverpool Record Office

The Pension Card suggests there were other reasons for grievance as well. Under ‘Remarks’ is handwritten, ‘£8.G rank Pd: 31-10-18’. Could this be the missing amount left out of the letter sent to Grandmother on 7 November? If it is, the dates do not tie up. Even if that handwritten remark does mean 8 pounds, relating to a Gunner’s rank, had been paid on 31 October, it does not diminish the harsh reality of nearly another seven months without any income. At best, it indicates that the family would have had to survive for more than half a year on a smidgeon over £1 per month, when the pension was going to provide more than that per week. This on the assumption that on the death of a soldier his army pay ceased, and with it whatever was remitted home.

That Grandmother’s circumstances were severely circumscribed is indicated by the Pension Card’s change of address. ‘Mrs. Edwards’ is Bridget, Grandmother’s sister, who lived at 25 Oak Street, Bootle (it is still there today), with her husband and four children. After Grandfather’s enlistment, Grandmother and her family left their home at 71Chetwode Street, Crewe (which is also still there today, first house in the half of the street that has avoided demotion) and moved in with them. She made the move expressly to be near her two sisters, the other, Maggie/Margaret, being housekeeper at the Webster timber importers’ premises near Liverpool docks. The existence of the Oak Street address on the Pension Record is problematic.

Clearly with Bridget having four children and a husband, the arrival of grandmother with her three boys created a degree of unsustainable overcrowding. As indeed it was, because Grandmother only stayed there until she found alternative accommodation at the corrected address the Pension Record shows, 1 Jersey Street. Furthermore it is certain Grandmother rented Jersey Street quite quickly, even possibly before the end of 1915. The only school of which Father ever talked was nearby, in Hawthorne Road, from which it took its name. (The School is now closed, all its records destroyed, according to the Local Authority.) It is also true that he and his brother always talked of having lived the War in Bootle, and specifically in Jersey Street. All their reminiscences of Crewe predated 1915.

If that is so, it is quite possible, even probable, Grandmother informed the authorities of her removal to Bridget’s, so that she could continue to claim her army pay at the local Bootle Post Office, instead of in Crewe. After she moved into her own house, she did not bother to give notice of the change of address, because there was no change in where she drew her money. The inference of this it that it may have been she who caused, or at least contributed to, the delay in her War Widow Pension assessment, the Pension Ministry having first to verify and process the different address. In support of this, it is noteworthy that Grandmother, if not illiterate, was no comfortable writer. There is one surviving piece of her handwriting. It is in a child’s deliberate hand.

This still does not completely explain why the home address on the Pension Record Card was altered. Manifestly it had to be changed, not least because the October condolence letter from Grandfather’s Section Commander was addressed to 1 Jersey Street, as was the Artillery’s October Notice of Death, as was all the surviving correspondence consequent upon the death. The unanswered question is why, if the military authorities had registered the change of Grandmother’s home address, did the Pension Ministry have the wrong one? Perhaps Grandmother did not contribute to the delay in assessment at all. Perhaps it was bureaucratic.

The Pension Record Card also reveals that there was yet another cause of dissatisfaction. Compared to Grandfather’s earnings before he enlisted, the pension of 29/7 at first sight appears generous. He was employed as a foundryman in the London North Western Railway (LNWR) Company’s works at Crewe. The employment records of the Company are available on the Internet. They show that, when he ‘enlisted without permission’, as his resigning in October 1915 is described, he was employee 6951, working under Foreman Savage, he had a good reputation in terms of timekeeping, character and ability, and his pay was 23/- (23 shillings, or 1 pound 3 shillings) per week. His widow was to be awarded 6/7 (6 shillings and 7 pence) more than this, crudely one third of a pound more. However this is not as it seems.

Between 1913 and 1919, inflation had been in double figures each year, peaking at 25% in 1916. It is also possible that the family home, in Chetwode Street, was in LNWR property. The terraced houses certainly look as if that was so, although the local Estate Agents consulted have not been able to confirm or deny it. The only known railway cottages in Crewe are few. They are protected historic buildings, and not in the immediate vicinity of Chetwode Street. If No. 71 was tied to Grandfather’s employment, the rent would have been less than Grandmother incurred in renting 1 Jersey Street. That together with inflation made her outgoings more than they had been in Crewe. Proof of that lies in the fact that our Father had to start working before he had finished his statutory schooling.

He often talked about this, with some pride. The facts never altered. 12 years old when his Father was killed, he was not eligible to leave school until after his 13th birthday, 10 months later. Nevertheless, in October 1918, he began work as lather boy in a local barber’s shop, the barber having taken him on for compassionate reasons. Father worked there each morning before school, each evening after school until 10 o’clock, and all day Saturday. He was paid 2/6 per week (otherwise known as half a crown - an eighth of a pound), which he gave to his Mother. He also earned 1/11 (a penny short of 2 shillings - a little less than a tenth of a pound), which he kept for himself. In July 1919, as soon as he could, he left school and began to work full-time for the barber, but he still did not bring home enough. By then his Mother was also working, in a local hardware store, which still exists. Family oral history indicates that a pension of 29/7 was inadequate for a family of a War Widow and her three sons. Nor is that all.

There is a parallel between the extant record of Grandfather’s commemoration at Tyne Cot and Grandmother’s Pension Record Card. Neither is backed by working papers. When the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (the CWGC) was asked about the location of Grandfather’s grave, the letter sent in reply stated, ‘After the war his grave was among those the Army Graves Service were unable to trace’. This seemed to suggest that at some time there had been a record of the burial no matter how vague. If this was the case, the papers of the Army Graves Service, in the immediate post-war period, might have been passed on to its successor. A second enquiry asked to see that documentation, only to receive the rebuff that the working papers had not been retained. It would seem to be the same with the Pension Record Card.

The Card contains two additions which look as if they were made after it had been completed. Both infer something unspecified had happened. Faintly, in pencil, below the date of the notification death, there is ‘24 3 19’, a date unrelated to the others on the line above. Similarly, in the box headed ‘Remarks’ appears ‘50729. 3 19’, written in blue ink, markedly different from the black ink and the handwriting in the rest of the document. Commonsense says that, at some time, there must have been a dossier, a file of papers, upon which the conclusions on the Pension Record Card are based. These two additions are an indication of that.

In the evaluation of the pension Grandmother was awarded, this is important, for there is nothing to say how it was calculated, how much was allocated for the widow herself, for each of her sons, and for back payment. The absence of these details masks something else. The pension was time-limited. The undisclosed allocations for the boys expired when they reached their 16th birthdays. In short, Grandmother was on a reducing pension. Delay, inadequacy of allowance, lack of information, time limit all taken together contribute to making a typically good cause for outrage, for a bitter sense of injustice. They make ‘one hell of a row’ understandable

Beyond this, the Pension Record hints at another aspect of the situation, which has nothing to do with money. Grandmother was not known as Mary. She was always Polly. How old was she, when her husband died? According to the date of birth on the Pension Card, she was 41. That makes her 2 years younger than he, which in turn means, because of his age, he did not have to enlist, especially as he had reserved employment with the LNWR. So why did he? With the initial ‘N’ for his middle name, the Pension Record tacitly explains why. The N stands for Nelson. He was Edward Nelson Lea, a proud imperialist. The only surviving piece of Grandmother’s childish handwriting is a copy of a poem. It starts with these lines:-

Only a dream, I know,

And yet it means I must be ill.

One thing a soldier said at last

That I remember still.

He said, We went to carry on

The work begun by Clive.

The poem was found by our Father amongst his Father’s medals and some of their associated papers, which had come to him after his Mother’s death. The full text makes it impossible to say whether Grandfather ever saw it, whether he and his wife ever shared it, or whether it was chosen by Grandmother to help her in her bereavement. It is indicative nonetheless. Although because of poverty Grandfather voluntarily enlisted in 1898 for the Boer War, he was always proud, so Father maintained, of his South African War service, despite being almost fatally wounded, or perhaps because he survived his wound. An enthusiastic Tory, he celebrated with characteristic exuberance, wearing his Party’s colours, when, in a 1913 By-Election, the Conservatives won Crewe for the first time. He was a Crewe Special Constable. Photocopies of roneoed letters calling him to training have been deposited in the Cheshire Police Museum at Warrington, and with them a group photograph of all the Specials, in which he sits in his three piece suit, the 1913 fob watch very much on display.

Ted Lea sitting fifth left next to the senior officer in uniform. He poses with fellow Special Police Reservists at Crewe in 1913. (In 1912 the Home Office instructed police forces to set up a special police reserve to be used in times of national emergency. The men received training but were not issues with uniforms. This group was the contingent formed in the Crewe division of the Cheshire Constabulary. At the start of the Great War most of these men were embodied into the newly-formed Special Constabulary in which Ted Lea served initially. Courtesy: the Museum of Policing, Warrington

When he enlisted without permission in October 1915, no doubt as a contemptuous old timer, the War was not going to be won by its second Christmas, anymore than it had been by its first. He signed up for imperialistic reasons, died for them too. Such convictions are hard to imagine today, but they lasted even beyond the Second World War. The Boys Junior School we both attended in Liverpool celebrated Empire Day into the 1950s, and it was organised in Houses named after imperial heroes - Drake, Wolfe, Clive and, but of course, Nelson. There is more in the Pension Record Card than meets the eye. Implicitly it accepts that Grandfather did not have to die as he did, Grandmother did not have to lose her husband. Her lot in life could have been very different. She should not even have had to leave Crewe.

Most of all, however, the Pension Record Card gives an insight into the circumstances of war widows, their kith and kin. It was not only the soldiers who were heroes and brave in all they endured.

Were it not for the Western Front Association’s First World War Pensions Service, and the work of its Curator, David Tattersfield, none of this would have been known, and Grandfather’s story would have remained incomplete. The huge archive to which the Service now provides access contains detailed information about individual soldiers and their dependents, which would otherwise neither have been available nor known. It gives a human insight into the sacrifice that so many made.

Notes:-

1. For the story of the research into Grandfather’s life and a reconstruction of his last weeks alive at home on leave and then back at the Front, see John Lea, Whatever Happened to Grandfather? Amazon Kindle Books, 2016.

2. Sadly, the watch was stolen during a burglary in 2013.

3. An Archive, comprising Grandfather’s medals, papers, documents and artefacts, all relating to his service in both Wars, was offered to the Imperial War Museum and refused, with a recommendation that it be given to the Imperial War Museum in Salford. It was refused there too, with the result that it has been placed in Liverpool Record Office. All the documents to which reference is made in this article, except for the War Diaries of the 14th (Light) Division held in The National Archives, can now be found there.

4. Peter Simkins, Kitchener’s Army; the raising of the new armies, 1914-16, Manchester University Press, 1988, p.225.

5. One of the gun pits still exists today, as a child’s sandpit, but not a tree stump of English Wood remains.

6. The value of money in 1919 was so different that converting it to decimal currency is largely meaningless. For example, when Grandfather enlisted in October 1915, he gave his eldest son, our Father, a penny as a parting gift. His son was so delighted he spent a halfpenny on sweets and a halfpenny on tin soldiers, with which he played pretending they were his Dad. Halfpennies were, of course, called Ha’penny, pronounced ‘hay-penny’.

JOHN AND DAVID LEA

John Lea is a retired Senior Lecturer and Education Officer

David Lea is a retired Senior Hospital Pharmacist

The example of the Pension Card in this article has been extracted from the WFA's Pension Archive. This archive is available for WFA member using the WFA Member Login.

Further reading:

Pension Record Cards - claims for soldiers who were killed

A further release of First World War Pension Records by Ancestry

Understanding the Ledger Indexing

Dear David ... Pension Record Cards Feedback

Release of Naval and Mercantile Marine Pension Records by Ancestry

Pension Records: Famous, Infamous, Extraordinary and Ordinary