'Rikki' Little: Australia's Greatest Ace

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'Rikki' Little: Australia's Greatest Ace

As the ‘Camel’ pilot approached dark shape in the gloom of the late May evening, he recognised it as a Gotha bomber – one of those that had been reported in the area that evening. Captain Robert Little - ‘Rikki’ to his comrades at 203 Squadron - could make out enough of the enemy machine in the moonlight to be confident that he would be able to bring down the slow moving bomber. Now he had located the enemy machine, it was just a matter of manoeuvring and avoiding the fire from the Gotha’s crew - at least Little would not have to worry about any German single seat scouts – there would be no escorts for this night bombing raid.

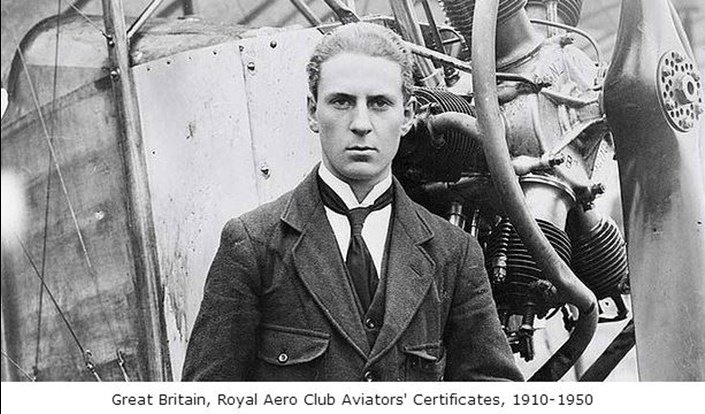

Captain Robert Alexander LittleDSO & Bar, DSC & Bar

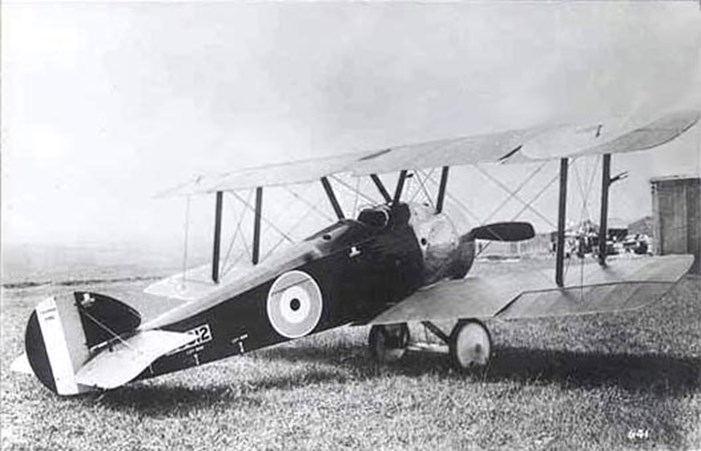

A Sopwith Camel. Image courtesy of earlyaeroplanes.com

A Gotha G.V

Gotha G. V. by Ivan Berryman. Bathed in the low winter sun over southern England, Gotha G.V.s are attacked by defending Sopwith Camels as the German bombers penetrate the south-eastern counties en route to London. Image courtesy of Cranston Fine Arts

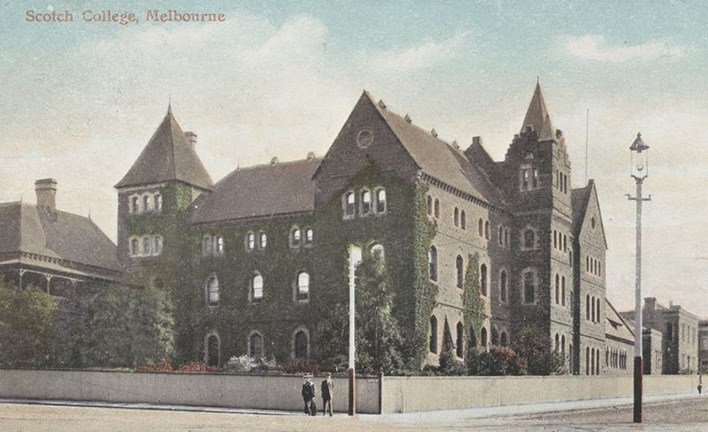

The Gotha was well defended with one forward and two rearward machine guns but it was a big target and even for a novice easy to hit. But Robert Little was no novice. He had brought down his first enemy machine in November 1916 when he was still a ‘rookie’ with Number 8 Squadron RNAS. Little soon became a popular member of the squadron, not only did his Australian accent set him apart but also his aggressive flying. Although not a brilliant pilot, his aggression in the air had earned him the nick name “Rikki” after the mongoose from Rudyard Kipling’s story Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. For most of his time with Naval 8 he flew a Sopwith Triplane – at one point he personalised his aeroplane (christened “Blymp”) by adding streamers from the wing struts in the cardinal, gold and blue of his old school (Scotch College) back in Melbourne. By a fortunate coincidence, the standard British message streamers (lengths of cloth attached to messages dropped from aeroplanes and also attached to aircraft to distinguish flight leaders) were in the same colours as his old school.

A Sopwith Triplane. Image courtesy of earlyaeroplanes.com

The cockpit of a Sopwith Triplane. Image courtesy of earlyaeroplanes.com

He accumulated 38 victories (3 while flying Pups, 25 from Triplanes and 10 from Camels) as well as the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished Service Cross and Bar and the Croix de Guerre before being sent back to the UK for a rest in July 1917. Two months later he was awarded a bar to the DSO.

With the turn of the year Little was promoted to Flight Commander had turned down a desk job and volunteered to return to France, eventually joining Major Raymond Collishaw’s 3 Squadron RNAS in March. With the formation of the Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918, this had become 203 Squadron.

Only the following day, 2 April 1918, he had a very narrow escape, his log book records:

…I was then attacked by six other E.A. (enemy aircraft) which drove me down through the formation below me. I spun but had my controls shot away and my machine dived. At 100ft from the ground it flattened out with a jerk, breaking the fuselage just behind my seat. I undid the belt and when the machine struck the ground I was thrown clear. The E.A. still fired at me while I was on the ground. I fired my revolver at one which came down to about 30 ft. They were driven off by rifle and machine gun fire from our troops.

He had carried on his run of victories, scoring nine official kills in the last two months. Five days ago he had claimed his 46th and 47th combat victories. He was convinced his score was much higher than this, but as the Gotha grew closer in his sights – he wanted to get close to make sure – he felt that it would only be a few days before he got to his ‘half century’.

Suddenly he was blinded by an intense light. One of the searchlights hunting the Gotha had caught him in its beam. Alerted to his presence, the gunners on the Gotha opened up and Little was hit in both thighs. Fighting to maintain control Little descended in a dive and crashed-landed in a field.

The following morning, 28 May, Little’s body was found and he was buried in a nearby cemetery. After the war he was re-buried miles to the south west at Wavans. This was probably a deliberate act by the Imperial War Graves Commission as his grave is within touching distance of that of Major James McCudden, VC, who died two months later.

Wavans British Cemetery

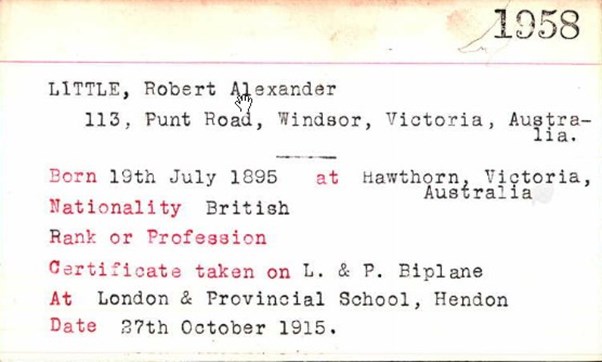

Robert had been born in Melbourne in 1895 to a Canadian father and Australian mother. Probably due to Scottish ancestors, he was educated at Scotch College, Melbourne. He did not do well academically, but was an excellent swimmer. He left school when he was 15, joining his father’s business, selling medical books. After the outbreak of the First World War he applied for pilot training with the Australian Flying Corps, but was rejected due to a massive surplus of volunteers. Not to be deterred, he travelled to the UK in 1915 and, at his own expense qualified as a pilot before volunteering for the Royal Naval Air Service. He was commissioned in the RNAS in January 1916. His operational experience started in June 1916 when he flew bombing raids in Sopwith 1½ Strutters out of Dunkirk. After a whirlwind romance, he married Vera Field in Dover in September 1916 before being posted to Naval 8 flying Sopwith Pups.

A Sopwith 1½ Strutter

A Sopwith Pup

Robert Little and his wife, Vera, had agreed that should anything happen to Richard, she would emigrate to Australia and bring up their newly born son, Alec, who was born in March 1917. This she did. The propeller of Richard’s aeroplane was fitted with a clock and presented to Vera. She re-married in the 1920’s, living until 1978 and surviving Alec by a year.

Although some more information about Little is available, including the citations for his medals, it is at this point that the story of Captain Little would normally end. However, a startling discovery has propelled this “unknown” ace into the limelight many years after his death.

It seems that the propeller clock was not the only item that made its way back to Australia.

Rooting about at the Texas Waste Transfer Station near Stanthorpe, Queensland (a waste tip) in early 2012, a ‘Gladstone’ type bag was found by someone who wishes to remain anonymous. Finding a mouse had made its nest in the contents, the finder emptied the bag of the rodent and various other items that had been used as nesting material and took the bag home. There it lay for a further eighteen months. It was only a few weeks ago that the finder decided to look into the bag’s contents. Inside was a leather helmet (originally believed to be a motorcyclist’s helmet), a silk shirt, a camel-hair vest, two pairs of “long johns” and a cravat. Other items were also in the bag, but the flying helmet (as it turned out to be) was not in good condition, the fur lining having come away (possibly as a result of the mice). It did, however, contain a strange lump, which was stitched into the lining. Taking it to a friend who was a vet, the flying helmet was X-rayed and the lump was found to be a piece of metal. Using forceps, the vet extracted this and it was found to be a British gold sovereign dated 1884, wrapped in a photograph of a baby boy.

Gareth Morgan, President of the Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians takes up the story:

....a few days ago I had an email from a bloke in the Queensland town of Stanthorpe regarding an old suitcase he found on a rubbish tip in Texas, Queensland, a couple of years ago. It contained an old flying helmet, a pair of goggles, a silk shirt, a camelhair vest, some old-fashioned underwear and some pressed flowers, and some other items. The helmet was marked with the name “R A Little”, and “Windsor, Victoria, Australia” something that definitely caught my attention, as Australia's leading fighter pilot of the Great War was Captain Robert Alexander Little DSO* DSC* (47 victories), who came from 113 Punt Road, Windsor. The shirt was marked with Deo Patriae Litteris - the Latin motto of Scotch College, Little’s former school. I was immediately rather suspicious, thinking of some small-scale ‘Hitler Diaries’ type hoax – the information about Little’s life and times could have come from Wikipedia, which tells us that he went to Scotch College and that he collected wildflowers as a hobby. Was I dealing with an honest country lad, or someone who had an idea of ending up with a fatter wallet?

Scotch College, circa 1906.

….I was apprehensive, and wondering how to verify that these were really genuine Little artefacts – the chance seemed pretty slender – when I thought of Mike Rosel, and his book Unknown Warrior. After seeing the form of the lettering on the cover of one of Little’s logbooks sent to me by Mike, and realising that it was very close to the style in the helmet, I thought that we couldn't take a chance of the finder opting to sell the stuff to a collector. There was an anxious moment or two when I saw that the finder had been enquiring about the value of the items on a couple of online forums, and at this point came the news about the X-ray at the vet and the finding of the coin and photo. I tried to persuade him that a museum was the best place, and that the Fleet Air Arm Museum [Nowra, New South Wales, Australia] was the most suitable, at the same time alerting the Museum’s Manager, who acted very quickly and arranged for a handover. The Manager was up in Queensland about two days later, and brought the bag and contents back to Nowra last Saturday. The finder was keen for the items to go to a small-ish museum, rather than somewhere like the Australian War Memorial, where they might disappear into the vaults, never to be seen again, so it all worked out very well.

Richard “Rikki” Little is one of the least well known First World War aces. Bishop (72), Mannock (61) Collishaw (60), McCudden (57) are all well known, but the next group of Beauchamp-Proctor (54) MacLaren (54) and Barker (50) and Little (47) are largely unknown.

Little’s Aviator’s certificate. Image courtesy of theaerodrome.com

Robert Alexander Little. Image courtesy of theaerodrome.com

It is hoped that this remarkable find will rekindle interest in Australia’s greatest “Ace”. A massive amount of credit is due to the anonymous finder for donating this material to the museum, as well as to Gareth Morgan of the Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians for facilitating this donation.

Any readers who are in New South Wales will soon be able to see the artefacts at the FAA Museum at HMAS Albatross which is on the outskirts of Nowra, about 175kms south of Sydney.

Further reading

Biggles’ Last Flight: the flying career of Captain WE Johns

Mike Rosel: Unknown Warrior - The Search for Australia's Greatest Ace.

Contributed by David Tattersfield,

with thanks to Gareth Morgan for his assistance with this piece.

See below for images of the contents of the Gladstone bag.