The New Zealanders at Polderhoek Chateau : November 1917

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The New Zealanders at Polderhoek Chateau : November 1917

The Third Battle of Ypres officially ended on 10 November 1917, but this did not mean fighting in Flanders stopped. Although at the end of the battle the high ground of the Passchendaele ridge was taken by Canadian troops, the front was still active. Only three weeks after the capture of the ridge, the highly regarded New Zealand Division was to be involved in one of the last actions of 1917.

Above: Canadian stretcher bearers carrying a wounded soldier through the mud of the Ypres Salient, 1917. © IWM CO 2252

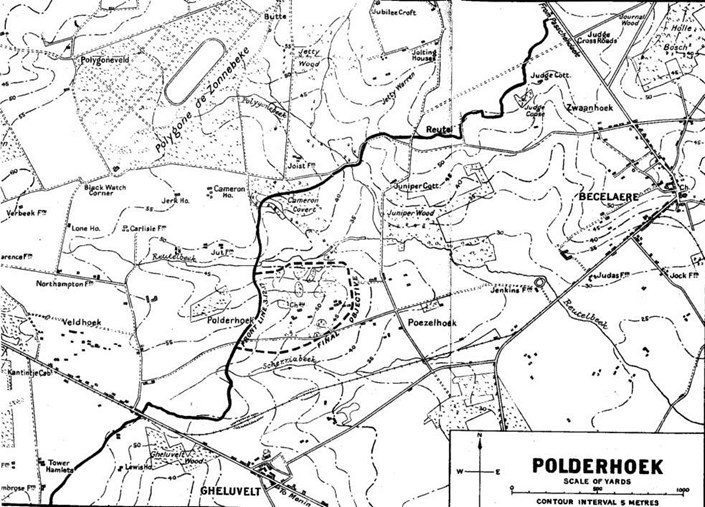

Only a few miles to the south of Passchendaele was Polderhoek Chateau.

Before the war Polderhoek Chateau was one of those pleasant Belgian country houses situated in the midst of beautiful woods and cultivated fields. But some time since the chateau and its contents went the way of all such things in the German war zone. The trees were whittled bare of branch and leaf and the fields were no longer good to look upon in all this region the Germans had made what, in the language of the soldiers, are known as "strong points."

Malcolm Ross, War Correspondent with N.Z. Forces in the Field. (Hawera & Normanby Star, Volume LXXIV, 22 March 1918).

Above: Polderhoek Chateau before its destruction by shell fire. Images courtesy of Paul Reed.

In late November, plans were drawn up for an attack on Polderhoek Chateau, this was to be made by two battalions of the 2nd New Zealand Infantry Brigade, part of the New Zealand Division. The chateau (or the remains of it) stood on high ground overlooking the British lines.

Above: Map of the area, with Polderhoek left of centre, with the final objective shown by a dotted line. Image courtesy of A. E. Byrne, The Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918 (J. Wilkie & Company, 1921)

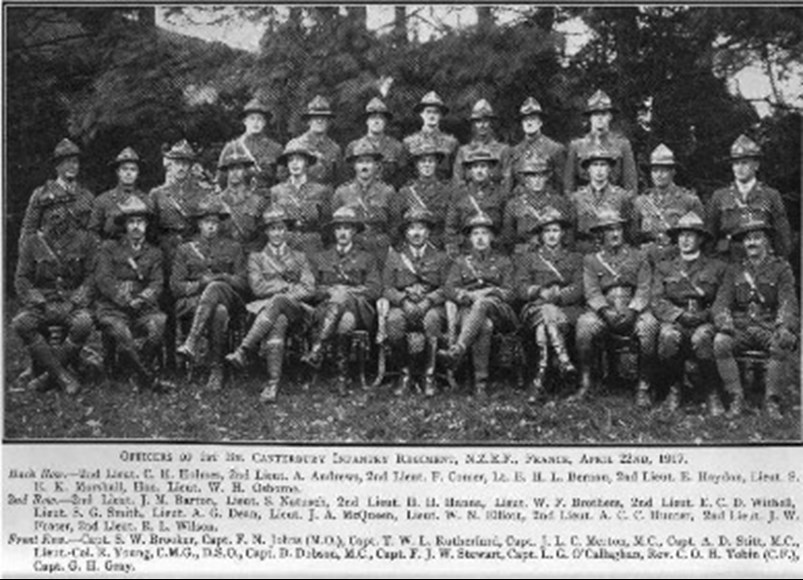

The two battalions selected for the attack (the 1st Battalion Otago Regiment and the 1st Battalion Canterbury Regiment) were withdrawn from the front lines and undertook training which included a practice attack over ground which resembled the objective.

Above: Canterbury Regiment officers April 1917. Image courtesy of Captain David Ferguson, The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914 – 1919 (Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, 1921)

Meanwhile, artillery fire was directed on the “real” target, but this brought about heavy retaliatory barrages from the Germans – clearly they were intent on retaining the strong point.

Orders for the attack were issued on 1 December, with the assault due to be made on 3 December. Each battalion would put two companies into the attack with another company in support and another in reserve. The intention was for each company to go ‘over the top’ with only 100 men – much less than the full strength of the company. This meant just four hundred men would be in the initial attack.

Commanding the 10th Company (one of the assaulting companies) of the 1st Battalion Otago Regiment was Captain C. Bryce.

The first objective was immediately to the east of the Chateau, with a second objective 200 yards ahead; the intention being to encircle the whole of the Chateau grounds and ruins. Supporting the assault was the inevitable artillery barrage; there was to be a barrage of machine gun fire and trench mortars would also fire explosive as well as gas shells.

The troops of the Otago and Canterbury Battalions moved up and took over the front line system west of Polderhoek Chateau on the evening of 1 December. By daylight on 3 December all troops were in position. Zero hour was at noon. The German wire entanglements had been destroyed by the British bombardments, but the barrage that opened up to cover the New Zealander’s assault fell on the New Zealander troops’ assembly positions, leading to severe losses. The only way for the troops to avoid this fire was to advance:

…some distance had to be covered before [the British Artillery barrage] was cleared, and by that time casualties, now increased by enemy machine gun fire, were so heavy as to seriously prejudice the success of the attack. It was during this stage of the advance that 2nd-Lieut. F. Marshall, of 4th Company [Otago Regiment], was killed, and that Captain Hines was wounded, though he continued to lead forward his Company. Approximately 150 yards beyond our old front line the second wave merged into the first. Captain Bryce, commanding 10th Company, was at this moment severely wounded, and while making his way back was killed. Command of 10th Company was taken over by Lieut. H. Digby-Smith.

AE Byrne, The Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918. (J. Wilkie & Company, 1921)

The advance faltered; but the situation was saved by Captain G. H. Gray, commanding the 12th Company [Canterbury Regiment], who, accompanied by Lance-Corporal Minnis, went forward and captured a pill-box about a hundred yards east of our front line and north of the road bounding the chateau grounds on the south, taking a machine-gun and eight prisoners. This enabled his company to get forward, in spite of the fact that the intensity of the machine-gun fire had increased very greatly. Later in the advance, the company was again held up by an enemy strong-point; but Private H. J. Nicholas, by capturing the position single-handed, gained the first Victoria Cross won by a member of the Regiment.

Captain David Ferguson, The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914 – 1919 (Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, 1921)

German machine gun fire came down on the assaulting soldiers, this coming from blockhouses which had survived the bombardment. Four minutes after the “zero” the German artillery had also joined in. Reinforcements were ordered up from the supporting companies, but they suffered heavy casualties and were unable to significantly alter the course of events.

A group of Australian soldiers quartered at one of the old German reinforced concrete pillboxes, known as 'Kit and Kat', near Zonnebeke. Image courtesy of The Australian War Memorial AWM E01069

Nevertheless, some groups of men managed to penetrate the interlocking zones of machine gun fire and the artillery barrage and made it to the remains of the Chateau.

Lieut. Digby-Smith and a handful of men reached a position which was actually in advance of the Chateau ruins, but were forced to withdraw for a short distance, and there hung on until blown out by shell fire. On the left of the attack a small proportion of [the Otago Regiment’s] 4th Company…had pressed on until they also were abreast of the main Chateau buildings, and in a position which gave them observation to the rear. Further advance was impossible against the heavy machine gun and sniping fire which the enemy, in considerable force, directed from the shelter of the ruins, from fortified shell-holes, and from a trench about 60 yards in length sited to the left rear of the Chateau. Our artillery barrage had some time since outstripped the infantry, and the smoke barrage was on the final line of the attack. Captain Hines was now wounded a second time and could only be carried out under cover of darkness…Command of this advanced group, numbering 12 in all, was taken over by Sergt. J. H. Wilson, M.M., who organised the party in shell-holes and set up a definite and determined stand against the enemy.

AE Byrne, The Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918. (J. Wilkie & Company, 1921)

With snow falling, and German counter attacks developing, the New Zealander’s ammunition started to run out. Eventually it was decided to abandon the offensive and consolidate the line held, which was no more than 250 yards in front of the original line.

VC Awarded

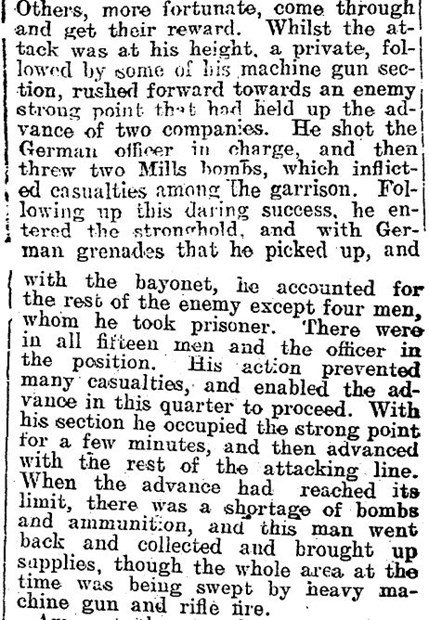

As mentioned above, a Victoria Cross was earned by a soldier during the course of this action. The details of the circumstances were detailed in the Hawera and Normanby Star on 22 March, 1918.

Hawera & Normanby Star, Volume LXXIV, 22 March 1918.

Above: Henry Nicholas.

For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty in attack. Private Nicholas, who was one of a Lewis gun section, had orders to form a defensive flank to the right of the advance, which was checked by heavy machine-gun and rifle fire from an enemy strong-point. Whereupon, followed by the remainder of his section at an interval of about 25 yards, Private Nicholas rushed forward alone, shot the officer in command of the strong-point, and overcame the remainder of the garrison of sixteen with bombs and bayonets, capturing four wounded prisoners and a machine-gun. He captured this strong-point practically single-handed, and thereby saved many casualties.

Subsequently, when the advance reached its limit, Private Nicholas collected ammunition under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire. His exceptional valour and coolness throughout the operations afforded an inspiring example to all.

The London Gazette, No. 30472, 11 January 1918

Promoted to Serjeant, Nicholas was killed in action on 23 October 1918. He is buried at Vertigneul Churchyard, Romeries. As with the vast majority of New Zealand CWGC graves, the headstone of Serjeant Nicholas does not bear any personal inscription from him family (this was a decision unique to the New Zealand government: other commonwealth nations allowed these personal inscriptions to be added to the deceased’s headstone). This decision of the New Zealand government, seems to have caused an uproar in New Zealand in the years after the war, part of this can be seen (including the reasons for the decision) in an article in the Evening Post of 3 June 1924.

New Zealand CWGC headstones: 'Personal Inscriptions'

There are, curiously, a number of exceptions to the rule that no New Zealand headstones should have a personal inscription. It is believed that there are at least six headstones of New Zealand soldiers which have such an inscription; five of these are buried in one of two cemeteries at Doullens in France.

In Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No.1 are:

Brigadier General Harry Fulton CMG DSO (“I THANK MY GOD UPON EVERY REMEMBERANCE OF YOU”);

Serjeant Harry Black (“HE DIED THAT OTHERS MIGHT LIVE. EVER REMEMBERED BY HIS FATHER AND BROTHER”)

and Private Donald McLean (“I AM THE RESURRECTION AND THE LIFE. INSERTED BY SORROWING PARENTS”)

Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension No.2 contains two men with these inscriptions:

Rifleman John Mair (“UNTIL THE DAY BREAKS AND THE SHADOWS FLEE AWAY”)

and Rifleman Alexander MacRae (“GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS, THAT A MAN LAY DOWN HIS LIFE FOR HIS FRIENDS”).

At Courcelles-au-Bois Communal Cemetery Extension there is just one New Zealander with a personal inscription:

Private Norman Williams (“BELOVED SON OF GEORGE & RUTH WILLIAMS BRISTOL ENGLAND. HE DIED FOR YOU AND I”)

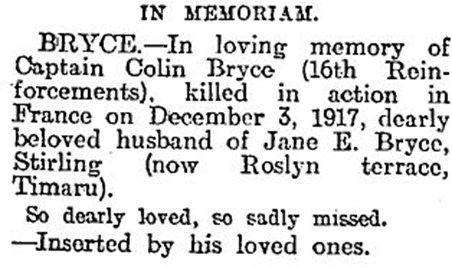

Captain Bryce – Otago Regiment

Captain Bryce, who had been killed during the attack at Polderhoek whilst leading one of the companies of the Otago Regiment was commemorated in the following years by his family via “In Memoriam” inserts in New Zealand newspapers:

Above: The insert in the 1918 edition of the Otago Daily Times , Issue 17488, 3 December 1918

Cemeteries and Memorials

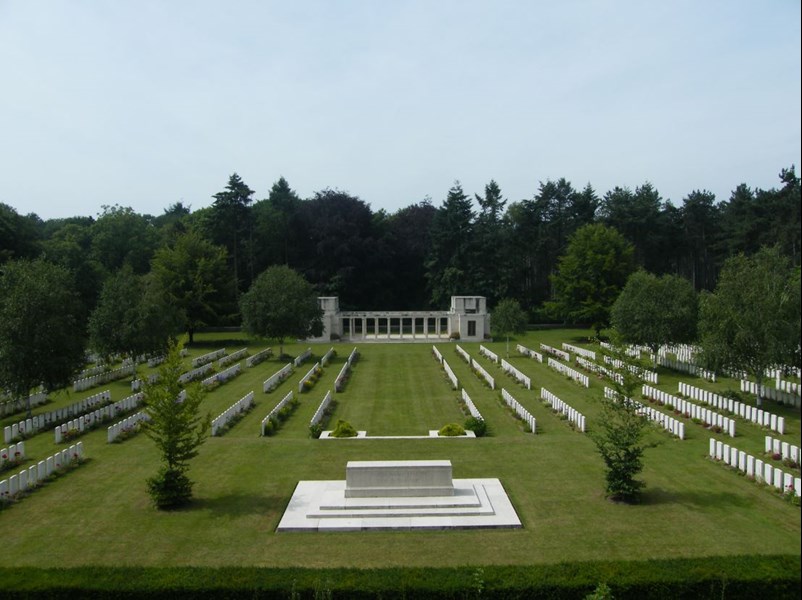

Of men who were killed on 3 December, 89 are commemorated at Buttes New British Cemetery (NZ) Memorial, Polygon Wood.

Above: Buttes New British Cemetery (NZ) Memorial in the background, with the cemetery itself in the foreground.

Above: One of the two panes listing the names of the missing on the memorial.

Two men are buried at Buttes New British Cemetery.

Above: Buttes New British Cemetery, with the 5th Australian Division’s Memorial in the background.

In addition to the above, 25 are buried at Hooge Crater Cemetery, five at Ypres Reservoir Cemetery, 3 at Tyne Cot Cemetery, 3 at Menin Road South Military Cemetery, and 2 at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Sources

The Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918

The History of the Canterbury Regiment, N.Z.E.F. 1914 – 1919