Cyrus Peck, Piper Paul and the Canadian Scottish at Amiens

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Cyrus Peck, Piper Paul and the Canadian Scottish at Amiens

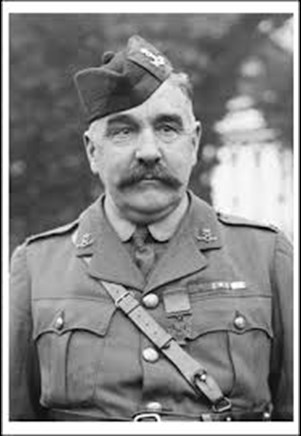

This article looks at one battalion's action on 8 August 1918, and is largely based on a chapter of the battalion's history by H.M.Urquhart, published in 1932. The battalion in question was the 16th Battalion, CEF the Canadian Scottish, a 'kilted' battalion which was led for a large part of the war by Lt-Col Cyrus Peck. It is fair to say he had strong views on the Scottishness of his battalion which perhaps helped to create an espirit de corps within this unit.

It is possible that even his closest friends and family would agree that Cyrus Peck was not built for speed. As a serving Member of the Canadian Parliament, he may have not have looked out of place in the House of Commons of Canada but as a serving officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he was certainly on the large side.

Above: Cyrus Peck

His service records tell us that although quite tall (5' 9") he weighed a fairly hefty 225lbs (16 stone).[1] Despite his bulk and 'Colonel Blimp' type looks, Peck was a capable and brave soldier.

Cyrus Peck was born in 1871 in New Brunswick. He seems to harboured military ambitions: as a young man in the late 19th century he travelled to the UK with the intention of joining the British Army to serve in the Boer War. Changing his mind, he returned to Canada joining the militia.

On the outbreak of the First World War he didn't immediately sign up, but within three months had volunteered. His papers tell us he described himself as a 'broker' but other sources suggest he was in the salmon canning business. As someone who had served before the war in the militia he was an officer who could expect rapid promotion, and so it proved.

Peck left Canada on 23 February 1915 with 30th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force with the rank of Captain.

This unit was destined to become a reserve battalion and send reinforcements to active units in France. As a consequence, Peck was immediately transferred to France and taken on the strength of the 16th Battalion CEF (The Canadian Scottish) in April 1915, with the rank of Major. The following month he was wounded and returned to the UK to recuperate. He was soon back with his battalion - returning to the front in July 1915.

Somme 1916

During the Battle of the Somme the 16th Battalion was in action in the Regina Trench area.....

The following passage is extracted from 'The pipes play on' by Tim Stewart

It was on the Somme that 18-year-old piper Jimmy Richardson and fellow pipers Hugh McKellar, John Parks, and George Paul played the advance in the assault on Regina Trench on 8 October 1916. On nearing the German position, No.4 Company of the 16th Battalion bogged down; the barbed wire to their front had not been destroyed, and casualties from enemy bombs and machine guns began to mount. The Company Commander was hit and Jimmy Richardson asked Company Sergeant Major Mackie if he could help: "Wull I gie them wund [wind]?" On getting the nod he struck up and played his bagpipes back and forth outside the wire for a full ten minutes.

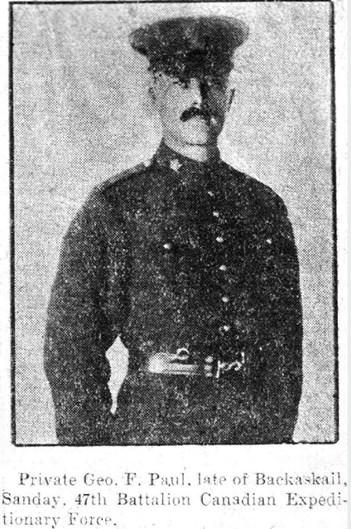

The troops' reaction was instantaneous - on hearing the pipes, they sprang at the wire, succeeded in cutting through, and went on to take the objective. Later in the day piper Richardson was helping move the wounded back when he realized he had left his pipes at the front. Although strongly urged to leave them, he refused to abandon his beloved pipes. He went back to retrieve them and was never seen again. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the only VC to a Canadian piper. Piper John Parks was killed this same day, Hugh McKellar was invalided out in 1917, and George Paul, would later receive a Military Medal at the operations around Hill 70 in 1917.

George Paul will come back into this story ...

Major Cyrus Peck was promoted to Lt Colonel and took command of the battalion in January 1917.

Vimy 1917

The war diary for the 9th April 1917 reports how Peck (with the HQ Pipe Major) went forward - each company of the battalion was led by a piper - and 'all objectives were reached'. Despite being unwell, Peck apparently commanded the battalion effectively, and established advanced Battle Headquarters in a German trench. The following day, with the attack successfully completed and the battalion relieved in the front line, Peck reported sick and was admitted to hospital. He was suffering from digestive issues - later classified as Dyspepsia. This had started with indigestion but became more marked with occasional vomiting. He was however able to rejoin his battalion in June 1917 and in the same month was awarded the DSO for distinguished service in the field.

Some of this 'distinguished service' was his man-management and leadership skills which can be evidenced in the battalion history.

Urquhart (Hill 70, 1917)

The following is extracted from H.M. Urquhart, The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish), Canadian Expeditionary Force, in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1932)

Above: The title page from H M Urquhart's 1932 battalion history

Colonel Peck possessed many gifts which fitted him for the command of men. He was a gallant fighter. He had a thorough understanding of human nature and a well balanced sense of humour fitted for every occasion. He had imagination; but what endeared him most to those who served under him, was his devotion to them and willingness to share danger, risk for risk, with the man in the ranks. He believed with a religious fervour that no such men as his own had ever lived before.

Major-General Sir Archibald Cameron Macdonnell, General Officer Commanding the 1st Canadian Division, tells a good story illustrating this trait.

'On the eve of the Hill 70 attack,' he writes [this was the attack by the Canadians in August 1917], 'I visited the 16th, arriving at billets as the Battalion was about to move off to the assembly area. I found the men gathered about their Commanding Officer [Peck]. They were listening intently to a stirring battle address the concluding words of which ran something like this: ‘The Brigade Commander, the Divisional Commander, the Corps Commander knows, and God knows you are the best of men-none ever better.’

"As a matter of fact," continued the General, “I had gone down to the Battalion with the intention of pointing out to the Colonel that certain matters in his unit might perhaps be done more efficiently. But after hearing the peroration I have quoted, criticism seemed out of place, and it was difficult to see what more could be said in the way of praise.”

[Peck] took a constant interest in all that affected the comfort and well-being of the members of the Battalion. He tried, as far as it was possible in a military organization, to make each man feel that he personally was being considered. ...Accompanied by his piper he always went forward with the Battalion in the attack; and sometimes, contrary to orders it must be confessed, ahead of it...Colonel Peck was not a Highlander and yet it fell to him as to few men of the Celtic race to make use of the influence which lies to hand in a Highland regiment to stir the blood, especially the most powerful of them all - the martial music of the bagpipes. The Commanding Officer inspired his pipers, and through their deeds the offensive spirit of the Battalion. “When I first proposed to take pipers into action,” he writes, “I met with a great deal of criticism. I persisted, and as I have no Scottish blood in my veins, no one had reason to accuse me of acting from racial prejudices. I believe that the purpose of war is to win victories, and if one can do this better by encouraging certain sentiments and traditions, why shouldn’t it be done? The heroic and dramatic effect of a piper stoically playing his way across the modern battlefield, altogether oblivious of danger, has an extraordinary effect on the spirit of his comrades.”

In accordance with these views, when the Battalion went into action five pipers accompanied it, one for each company and the Colonel’s piper. Each piper played two tunes, and two only, the company tune and another, these tunes being made known to all ranks before battle.

Men of the 16th Bttn (Canadian Scottish) moving up to the front line near Inchy during the Canadian Corps crossing of the Canal du Nord, 27 September 1918 (IWM CO3289)

To such a course of action there were raised, naturally, in these days of practical men whose imaginations have dried up, many objections. “There is too much noise, you can’t hear them,” they said. “It was not so!” again to quote Colonel Peck. “True, there were moments when there was a roar when nothing could be heard, but this was not for long. When you got under the enemy’s barrage, which was only the work of a few moments, and when your own barrage got ahead of the advance, which generally happened, after the first one or two ‘lifts’ of the artillery, the skirl of the pipes could be heard for a considerable distance.” Then there was the objection as to the loss of life. “Pipers are conspicuous,” said the doubters. “Well,” as Colonel Peck wrote in reply to this criticism, “that is part of the game. Officers, machine gunners and runners are conspicuous. People get killed in war because they are conspicuous; many get killed when they are not, and that’s part of the game, too.” The way in which the pipers themselves responded to this lead proved that they were but being summoned to their old proud post of honour on the battle front. They were again men of arms, Highland soldiers, not fatigue men of the quartermaster’s stores or clowns of the vaudeville stage.

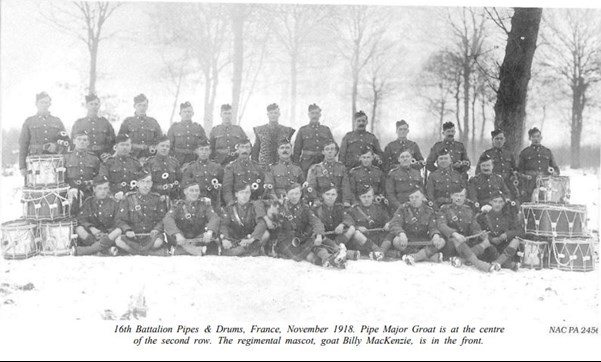

Above: The 16th Battalion Pipes and Drums, France November 1918 (National Archives of Canada)

Parliament

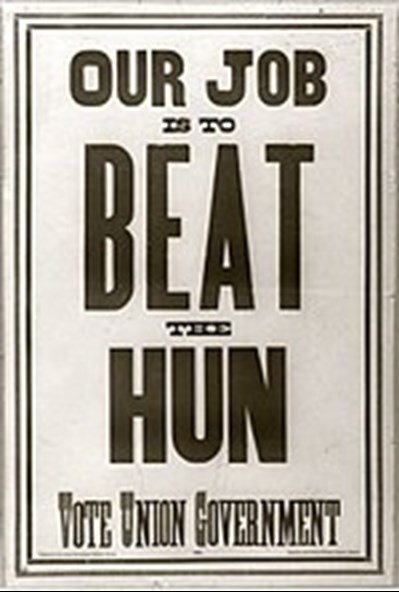

Although a serving officer, Peck stood for election in the Canadian Federal elections. These elections took place on 17 December 1917 (only days after the explosion in Halifax). Peck stood as a Unionist candidate (a party formed to fight the election, mainly out of Conservative party). The result was a landslide for the unionists and Peck was elected as member for Skeena.

A unionist poster for the 1917 elections

The Battle of Amiens: 8 August 1918

By the summer of 1918 the war had evolved - semi-open warfare conditions had, for a few weeks, been encountered during the German spring offensives. These battles had not involved the Canadian Corps, led by Currie.

Above: Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Currie of the 50th Regiment, Gordon Highlanders of Canada. January 1914. When the 16th (Canadian Scottish) Battalion, CEF, was created in 1914, it drew on soldiers from four separate regiments – the 50th Regiment (Gordon Highlanders of Canada) in Victoria being one of these. There is therefore a direct link between Sir Arthur Currie and the Canadian Scottish.

Therefore when the Allied counter-stroke at Amiens was being planned, it was inevitable that the Canadians would be involved but it was also vital that their proximity to the front before the battle commenced be kept from the Germans.

On the eve of the battle, the Canadian Scottish (part of the 1st Canadian Division) moved forward into trenches held by 49th Battalion AEF who were in the Gentelles / Hangard area, close to the River Luce a few miles south of Villers-Bretonneux.

Piper Paul

In the attack on 8 August Lt Colonel Peck's personal piper was Private George Paul, a 39 year old who had been born in Kirkwall, in the Orkney islands but who had emigrated to Canada before the war. Enlisting in Vancouver in March 1915 George Paul described himself as a seaman, who had seemingly sailed from Montreal a few weeks before enlisting.

Urquhart again: The attack at Hangard

The following is extracted from H.M. Urquhart, The History of the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish), Canadian Expeditionary Force, in the Great War, 1914-1919 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1932)

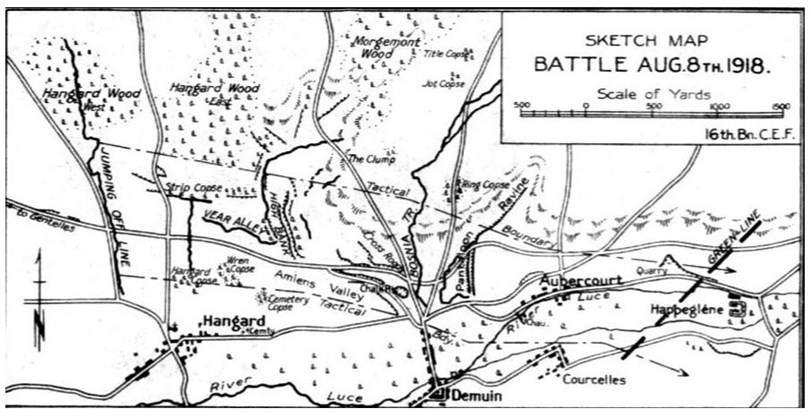

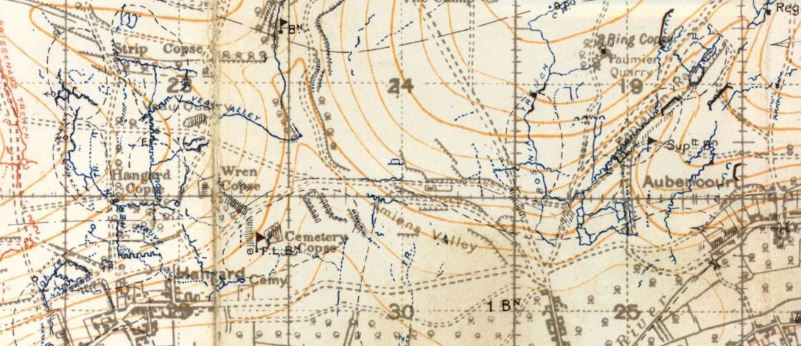

The ground to be covered by the 16th on its battle front was varied; of a nature peculiarly suited to the defence and correspondingly difficult for assaulting troops to advance over. Level at first, covered with fields of standing overripe rye and the shattered stumps of Hangard, Wren, and Strip Copses, it fell away some eight to nine hundred yards forward into a broad, deep hollow, on the farther side of which lay the steep terraced northerly slope of the Luce valley. As far as Bosnia Trench, the Battalion was responsible for the capture of this slope from top to bottom. [This is the site of Demuin Cemetery - more on this later]

Thereafter its attack inclined somewhat down the slope, and swung to the right to take in the village of Aubercourt, the Luce stream and its southerly bank.

The Battalion plan of attack‘ was as follows—Numbers 3 and 4 Companies (right to left, Major T. C. Floyd and Major Render) both in line of sections, in file, formed the first wave of the attack. They dealt with the situation up to and including Bosnia Trench. Two platoons of Number 2 Company (Captain Jones) formed a line of “moppers up” in rear of the first wave.

Lieut.-Colonel Peck was in command and Major Scroggie acted as his Second in Command.

Seven tanks in two sections were allotted to the Battalion, and one mobile brigade of Field Artillery accompanied the 1st Division’s attack to take on targets after the main barrage had ceased.

The assembly of the Battalion was completed without accident. The starlight night was ideal for the operation, clear and yet sufficiently dark to cloak movement. Twenty minutes before zero hour weather conditions swung to the opposite pole; a dense mist rose from the Luce marshlands and enveloped the Corps’ battle front.

When at 4.20 a.m. the barrage came down, the Battalion was able to close up to it, and advance in its wake unhindered by any counter barrage, or a single shot from the enemy’s outposts.

The wide No Man’s Land, which the unit had first to traverse, was untouched by the shell fire. It was soon crossed. Paths had been cut through the enemy’s wire and it afforded no obstacle; but on approaching nearer to the German defences progress became less rapid. The supporting artillery barrage had struck here in its full force, the smell of the newly torn earth rose strong from the ground; the fumes of the high explosives and the smoke screen, held close down by the clammy fog, got into the men’s eyes and throats and caused them to stumble, lose sense of direction and group together. The consequent confusion was in no wise improved by the arrival of the tanks which lunged around in a disconcerting way.

The story of the fighting in the enemy’s outpost zone is therefore disconnected. It relies upon the narratives of leaders not co-operating with each other, although, in themselves, these give a fairly accurate idea of the general characteristics of the attack at that stage of the battle.

Above map from H.M. Urquhart, The History of the 16th Battalion

'We passed through to the south of ‘Strip Copse’,' proceeds one account, 'and down the hill in front of us at a location which I judge to be between Vear Alley and Wren Copse I could see something that looked like an emplacement. Piper Maclean of Number 2 Company was with my party at the time. I told him to play 'The Drunken Piper' and to the strains of this tune, played in quick time, we charged. It was an emplacement sure enough, of heavy trench mortars. Jumping into the trench we saw in front of us the entrances to two dug-outs each guarded with a machine gun mounted and well camouflaged. We shouted down to the enemy and up they came - one officer and about sixty men. They were taken completely by surprise; some of them were in their stocking feet and partly clad. Arrived above ground they seemed determined to ‘dish up’ their day’s rations, and make themselves comfortable before starting the journey to rear, but after some gentle persuasion we settled that matter and sent them quickly on their way at the double. Soon after, to the north east of Cemetery Copse we ran into another party of Germans, about twenty in number, and hurried them back.'

'All Went well with us at the start,' runs another description of the fighting more to the left of the Battalion’s front. 'We had advanced seven to eight hundred yards without meeting any of the enemy and were passing through a field of rye, when suddenly somebody rose up right in front of me. I stopped, told the men to get down, and challenged. The man in front ran so I fired dropping him. I doubled ahead, followed by the platoon and found a big German shot through the face, breathing his last. On looking round I discovered two more of the enemy standing watching us from a ‘T’ head listening post. They surrendered without a fight, were sent back, and again we advanced, but had not gone far when I heard a noise in front and running ahead caught sight of a Hun setting up a machine gun. I shot him, and the section corporal and myself jumped into a short trench, which we found led to a trench mortar battery—a most elaborate emplacement—in a clump of trees close by. Looking around we discovered the entrance to a deep dug-out down which I shouted and up came an officer and about thirty men. I called for a volunteer to take the prisoners back but no one wished to go. I was on the point of detailing a man for the duty when conveniently two of Number 4 Company, with a big lot of Germans, passed us and I attached our group to them.'

Above: Trench map of area showing Hangard, Wren and Cemetery Copses. Also Bosnia Trench just west of Aubercourt.

Meantime Lieutenant Mackie and his platoon who were operating in the centre of the attack, and who were on guard for the breach in front, had good reason from actual experience to know that it existed. They had disposed of one machine gun and were fired on by another from their right rear.

'I placed the men in cover,’ Writes this officer describing the latter incident. “Took the Lewis gun corporal and two men and started back to investigate. On the rising ground on our right was a clump of trees and in them a machine gun nest. Just as we attacked it from one side, Sergeant Mowatt and men of Number 4 Company attacked it from the other and soon all was over. I was certain now that the gap in front had not been covered. I had a talk with Mowatt and took the necessary precautions.'

Passing from the enemy’s outpost zone the Battalion entered the broad hollow, which cut northward into the Luce slope. By this time its front was well covered. One or two platoons on the south, near Cemetery Copse, even overlapped the right boundary line into the area of the Canadian Mounted Rifles, but on striking the Hangard-Aubercourt road these men eased back into their own area.

The Battalion reached the bottom of the dip and there met with a strange experience. Through the fog there loomed up directly ahead of it a high dark mass, which at a first hurried glance seemed like a strong fortification. The first part of the Battalion to see it was the centre, where at the moment the Commanding Officer was present. Colonel Peck gave the order to charge. The men at once rushed forward, some thirty yards or so, only to find themselves up against an almost perpendicular bank.

For a moment all ranks were nonplussed. A doubt arose as to whether the Battalion was on its right course. Any misgivings on that point, however, were soon set at rest. It was discovered on feeling out to the right that the incline became much more gradual in that direction, jutting southwards towards a road, which was recognisable by the sound of the tanks creeping up along it, as the Gentelles-Aubercourt.

Groping its way over this slope, where it was most easily negotiable, the main body of the Battalion, less part of Number 1 Company whose exciting experiences will be related later, advanced to the attack. Piper Paul mounted one of the tanks, named 'Dominion;' the pipes skirled out the 'march past' of the Battalion, 'The Blue Bonnets over the Border;' and with this dramatic lead the troops on the right flank moved towards the enemy.

Above: Private George Paul - The Colonel's piper in the attack at Amiens on 8 August 1918 (www.veteransgc.ca)

Below: 'Blue Bonnets over the Border' (those of a nervous disposition may not want to hit the 'play' button !)

Daylight had now come. The fog was growing thinner. It became possible to see some little distance in front. Anti-tank guns and trench mortars were standing around in the open with their covers still on, but no enemy was in sight.

For some hundred yards the advance proceeded without interruption. The fog gradually lightened, until just as the leading wave of the Battalion’s attack was moving up the long grassy slope above the Aubercourt road north of Demuin, the mist cleared without a moment’s warning.

...It is now appropriate to break into Urquart's narrative. As previously detailed, Peck had seemingly acknowledged the risks associated with being the Colonel's piper due to the soldiers playing the pipes being 'conspicuous'. The odds on bagpipers surviving was probably lower than other troops. It is likely they would not be afforded the opportunities to take cover during 'fire and movement' advances as other troops and would be expected to stand upright during the advance so as to be able to play the bagpipes. We will never know if the German machine gunner targeted the Colonel's party, and it possible that George Paul was not piping the troops into action at this point, but in this attack George Paul was to be one of the inevitable casualties of Peck's tactical ideas....

Urquhart yet again

The Commanding Officer, who for observation purposes had again come forward into the first wave, hastened ahead to the crest of the ridge, and as he reached it an enemy machine gun opened fire in his direction at point blank range, killing Piper Paul, who was marching alongside of him. Simultaneously revolver shots rang out from the right front, the enemy gun ceased firing and Captain Alec MacLennan, the Battalion Intelligence Officer, appeared in the enemy’s post.[2]

MacLennan during the battle had a roving commission. After taking part in the fighting in the outpost zone, he struck down to the right and advanced along the Gentelles-Aubercourt road to the Demuin cross roads. From there, accompanied by one of his scouts, Private Frank Durham, he went north, up the shoulder of the hill, until he reached a knee - deep trench (Bosnia), which ran in the same direction. Jumping into the trench he had proceeded but a short distance along it, when he observed, around a traverse, four or five German machine gunners coming towards him. He rushed them; they fled and two succeeded in getting away. When he was following up these two, the fog lifted and he could see in plain view to his left the main body of the Battalion coming over the crest of the rise. An enemy machine gun crew from a position close by him, likewise saw the Battalion and opened fire on it. MacLennan, because of an intervening mound of earth, could not see the gun, but a few seconds afterward, on turning a further traverse, he observed it about thirty yards distant. He raced across the intervening space, shot the crew and on turning round, to quote his own words, “was amazed to see Colonel Peck coming towards me only fifteen yards away.”

It was evident that the serious stage of the day’s fighting had begun. MacLennan had disposed of two machine-gun crews opposite the centre of the Battalion front and eased the situation in that particular area; but the enemy was active against both flanks. On the right of the Battalion front he occupied a chalk pit in strength, and had manned Bosnia Trench beyond this stronghold; on the left, six to seven hundred yards distant from the Battalion, on a commanding shoulder of the hill, stepped with high ledges, he had posted further machine guns and snipers, who, with deadly aim, were picking off the leaders one by one. Render, commanding Number 4 Company, was killed here and Floyd, commanding Number 3 Company, wounded.

Without any hesitation the right flank attacked the chalk pit. The garrison fought stubbornly, but thanks to the fine leadership of Company Sergeant-major Frank Macdonald of Number 4 Company and Sergeant Wann of Number 3, its resistance was soon overcome. A large number of prisoners were captured here, including a battalion commander and headquarters and also a dressing station and doctor who rendered service later in aid of the 16th wounded.

Fairly heavy casualties were sustained in this attack, but fortunately Lieutenant Mackie of Number 1 Company and his platoon were at hand to reinforce. The advance was continued towards Bosnia Trench, only to be held up by heavy machine-gun fire from the right.

Mackie, ordering his men to remain under cover, crept out, accompanied by his Lewis gun corporal, into the ditch running alongside the Demuin road. On reaching this cover they gradually worked along to a point where, unseen, they obtained a direct view of Bosnia Trench. Crawling out of the ditch to gain more complete observation, they discovered the trench was defended by four machine guns. They waited until the crews exposed themselves. Then the corporal opened fire on the one directly opposite him and got all five members of it. Next time the Germans came into view he got two of the crew on the right, and on their third appearance he inflicted further casualties.

Ammunition now ran short, but a fresh supply was soon secured and fire was reopened directly one of the enemy showed himself. This sniping went on until the officer in charge of the German guns stood up, and waved to signify he wished the Canadians to come over. Mackie stood up and waved to him to make the advance. They looked at one another, hesitated, and started to walk towards each other. When they were about thirty yards apart the German drew his revolver; Mackie did likewise, fired, dropped his opponent, and, closely followed by the Lewis gun corporal, rushed the trench. The survivors of the gun crews immediately threw their hands up.

Bosnia Trench on the right flank of the 16th front was now in possession of the Battalion, and the troops operating there were at liberty to co-operate by flanking movement with the main Battalion attack.

On the left the Commanding Officer halted the advance until the snipers and machine guns, firing from the high ground to that flank, could be dealt with.

The advance continued with little or no opposition but in Aubercourt village a machine gun opened up, killing Lieutenant McConechy and Sergeant Barrett.

On the slopes of the ridge to the north the battle did not seem to be proceeding so favourably. From that direction came the incessant rattle of machine guns. The Commanding Officer, becoming anxious, ordered Captain MacLennan, to take a party east along the Aubercourt-Happeglene road. MacLennan’s party started and all went well until it rounded a bend in the road a few hundred yards beyond the cross roads north of Aubercourt. There, at a spot devoid of cover, it met with heavy fire at about two hundred yards range from a quarry directly in front. Before the men could disperse nine out of the fourteen were hit. Attached to the group was a Lewis gun and crew from Number 2 Company. The Numbers 1 and 2 gunners on coming under fire instantly dropped and came into action from the centre of the road, MacLennan lying to the left of Number 1, as observer. When the pans of Lewis gun ammunition were emptied, the gunners coolly picked up the rifles of the casualties and kept shooting until the enemy’s gun was silenced.

The report of this last check reached the Colonel at Aubercourt cross roads as a tank was moving past. He halted it; told the officer in charge, of the situation in front, and asked him to deal with it. The tank went ahead up the Happeglene road, followed by a group of 16th men, which was joined later by MacLennan and the survivors of his party.

The fight was over. The Germans at the sight of the tank at once surrendered. When the 16th men arrived at the quarry, they found that it sheltered a regimental commander, his staff and a large number of men—a big prize. Six enemy dead were seen lying around the machine gun which had held up the 16th advance, the last victim being the officer.

Speaking of the conduct of the two Lewis gunners who inflicted these casualties, MacLennan says, “I never witnessed a braver deed. Their coolness, courage and marksmanship in the face of great danger was remarkable.”

As the prisoners were being collected the main body of the Battalion under Major A. Scroggie arrived. Scroggie intimated that the opposition on the high ground north of Aubercourt had been overcome and ordered the advance to continue to its final objective, the “Green Line” in the Happeglene valley. This was reached between eight and 9 a.m. without further casualties.

Fatalities and the Battalion cemetery

For such a successful attack, the battalion casualties were quite light, however there were a number of fatalities, which research has revealed number 45. The majority of these men (27 in number) are buried at Demuin British Cemetery, which is adjacent to Bosnia trench - one of the objectives of the battalion attack. Most of the other men from the battalion who were killed in the attack are buried nearby either in Hangard Wood British Cemetery (4 burials) or in Hangard Communal Cemetery Extension (8 burials). A further five men from the battalion are buried in five different cemeteries, with one of the men having no known grave and being named on the Vimy Memorial to the Missing.

Above: Demuin British Cemetery. The majority of graves in this tiny cemetery are from the 16th Battalion. The grave nearest the camera is that of Piper George Paul, MM. (Author's collection)

Later in the war

Peck continued to lead his battalion for the rest of the war and was awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions at Cagnicourt on 2 September, less than a month after the action at Amiens.

The citation for the VC reads:

For most conspicuous bravery and skilful leading when in attack under intense fire.

His command quickly captured the first objective, but progress to the further objective was held up by enemy machine-gun fire on his right flank.

The situation being critical in the extreme, Colonel Peck pushed forward and made a personal reconnaissance under heavy machine-gun and sniping fire, across a stretch of ground which was heavily swept by fire.

Having reconnoitred the position he returned, reorganised his battalion, and, acting upon the knowledge personally gained; pushed them forward and arranged to protect his flanks. He then went out under the most intense artillery and machine-gun fire, intercepted the Tanks, gave them the necessary directions, pointing out where they were to make for, and thus pave the way for a Canadian Infantry battalion to push forward. To this battalion he subsequently gave requisite support.

His magnificent display of courage and fine qualities of leadership enabled the advance to be continued, although always under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire, and contributed largely to the success of the brigade attack.

Above: Peck's impressive array of medals.

Below: Wearing his newly awarded VC

Above: Peck leaving Buckingham Palace after the investiture for his VC

Battalion VCs - a record for one battalion for separate actions?

It is without doubt that his personal leadership was inspiring to all officers and me of his battalion. No fewer than four members of the 16th Battalion were awarded the Victoria Cross: Piper James Cleland Richardson, Private William Johnstone Milne, Lance-Corporal William Henry Metcalf, and of course Lieutenant-Colonel Cyrus Peck. Other than the award of multiple VCs for one action (for example 'Lancashire Landing' at Gallipoli) this may be one of the highest 'VC counts' for a single battalion in the First World War.

Above: the Canadian Scottish battalion's cap badge

After the war

Peck was defeated in the 1921 Canadian election but in 1924 he was re-elected to the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia and was re-elected again in 1928.

Above: a 'flyer' for one of his subsequent election campaigns. Clearly he was not above using his VC award to garner votes !

In the 1920s the famous war artist Eric Kennington was commissioned to create a work representing the 16th Battalion in the war. This was originally entitled 'The Victims'. After its showing in Canada led to objections about the title from Lieutenant-Colonel Peck, Kennington renamed it The Conquerors.

Retirement death and legacy

Following his political career Peck became a member of the Canadian Pension Commission.

He died on 27 September 1956 and is buried at New Westminster Crematorium, Vancouver. His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. A plaque inside the House of Commons, Ottawa, Ontario is dedicated to his memory.

As far as is known, he is the only Member of Parliament to have been awarded the Victoria Cross.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Notes:

[1] Peck's service history is available on line HERE

[2] The citation for the MC awarded for McLennan in this action is as follows:

'He played an important part in keeping the Battalion in proper direction through the dense mist of smoke. At one point a portion of the Battalion being held up by a determined machine gun (sic), he crawled round through a sunken road alone and came on the machine gun crew of five from a flank, shooting them all with his own hand. In the last stages of the advance he took forward a party and captured a regimental headquarters with the regimental commander and his entire staff. He showed the greatest courage, determination and skill throughout'.

Further Reading:

Urquhart, H. MacIntyre (1932). The history of the 16th battalion (the Canadian Scottish) Canadian expeditionary force in the great war, 1914-1919. Toronto: The Macmillan company of Canada, limited. This book is available online

Zuehlke, Mark (2008). Brave Battalion: The Remarkable Saga of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish) in the First World War: John Wiley & Sons