Doc ‘Pete’: A Baltimorean with the Royal Fusiliers, 1917-18

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Doc ‘Pete’: A Baltimorean with the Royal Fusiliers, 1917-18

As the US went to war in April 1917 without tanks, aircraft, heavy artillery, or more than a handful of infantry divisions, a legion of its physicians readied themselves for immediate deployment to the Western Front. In a twist of irony, the first US soldiers sent to France and Flanders were armed only with the Hippocratic Oath. This vanguard established the first US base hospitals near the front a full month before the arrival of General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) headquarters. And many doctors, especially those belonging to the US Army Medical Reserve Corps (USMRC), were individually embedded with Entente units to gain experience treating combat wounds and refining surgical techniques. Most of these physicians went to the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to serve with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). Their arrival was timely as the Spring campaign did not end well for the Allies.[1]

The much anticipated French promise of a 1917 final victory through combined Anglo-French assaults in the Artois region ended in stalemate. And for the French Army, in mutiny. Conducting offensive operations on the Western Front thus fell exclusively to the BEF for the remainder of the year. By June 1917, a personnel plan, which initially focused on gradually handing over control of six British base hospitals to American doctors, included rotating exhausted British medical officers (MO) with their American counterparts down to the Casualty Clearing Stations and infantry battalions in the trenches.[2]

One such officer was a jovial and talented 30-year-old Lt. William H. Toulson.

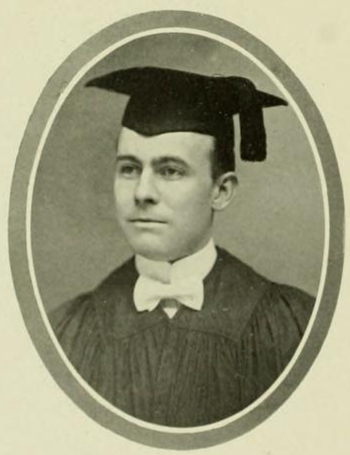

Dr. Toulson graduating in 1913 from UMD.

Hailing from Chestertown, MD, Toulson began his studies at Washington College. Following his BA, he left the Eastern Shore for the University of Maryland Medical School earning his doctorate in the class of 1913. Two years later, he was married, raising a family in Bolton Hill, Baltimore, and practising urology. When the US entered the war, he quickly sought a commission in the USMRC. After a rigorous selection and preliminary training process stateside, Toulson embarked for England to further his practical education. Then, he deployed to France in June. After serving in base hospitals for a time, he ultimately arrived in the trenches. On 30 October, he reported for duty with the British 37th Division’s 49th Field Ambulance Company (FA).[3]

Above: the Memorial to the 37th Division at Monchy

The 37th was a workhouse formation. Trusty and competent. Recognisable by its cherished golden horseshoe shoulder insignia (worn on both arms), it had been on the Western Front since July 1915. Raised from the last wave of volunteers in Lord Kitchener’s New Army, it battled through the Somme and Arras campaigns, where it concluded 1917 grappling with the Germans in the despised Ypres Salient. Once he reported to the company HQ, Toulson immediately assisted the 49th FA in commanding medicos and casualty clearing staff. Encamped astride what was left of the Comines Canal, ‘Pete’ (his collegiate nickname) relayed the circumstances in a letter to his school fraternity… “I am writing this within half a mile of the front-line trenches, sitting in my dugout. I am in charge of an advanced dressing station where the wounded are brought in by stretcher bearers from the trenches.” He continued… “the country around here is beyond description, and no one can realize the desolate waste until he sees it. The landscape is one vast sea of mud and shell holes and the ruined villages are rat-infested; but with it all life is exhilarating and interesting.”[4]

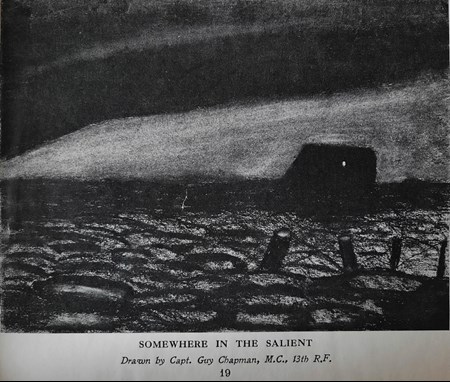

Two weeks before Christmas, he was finally transferred to an infantry battalion, the 13th Royal Fusiliers (RF). Their most able and admired MO, Capt. Mackwood, recently decorated with the Military Cross, was sent on an overdue leave to England as Toulson took over his duties.[5] In that role, Toulson appeared in one the finest war memoirs ever written; A Passionate Prodigality (1933) by Capt. Guy Chapman, then the battalion adjutant. The book benefited from the perspective of a historically minded and well-read young man deftly blending memoir with unit history in emulation of Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War (1928).[6]

The 13th RF would miss Mackwood, but “in compensation” Chapman wrote, “we received a sturdy round-faced American doctor from Baltimore, of a humour and ingenuousness to smooth our churrish insularity.”[7] Rumour quickly spread through the ranks that the new Yank MO was a most compassionate fellow and earnestly (if liberally) granted medical excuse from duty. The daily queue of 12 men before the medical tent, however, incrementally compounded until it reached roughly 50 when, much to Chapman’s amusement, it dawned on Toulson that many of these Tommies afflicted with cases of constipation, heart murmurs, and piles were “guying” him. In short order, the patients thereafter were sent back with the simple diagnostic prescription of his predecessor’s brusque fashion: “M&D” (medicine and duty). Despite this turn in charity, Toulson cheekily defended himself telling Chapman, “If any arms or legs drop off during the day, you surely will not blame me.” “If any do” Chapman retorted, “you can hang them in the aid-post as a souvenir.”[8]

Above: The Battle of Albert. An American doctor examining walking wounded of the 37th Division passing back along a road at Bucquoy, 21 August 1918. (IWM Q 11755)

Spirits eventually lifted as movement returned to the front in the wake of the final German Spring offensives of 1918. The combat over the lunar cesspools of Flanders brought Chapman and the 13th RF to breaking point. Fortunately, the 37th Division was spared the full brunt of these initial assaults as it successfully recuperated and prepared for the summer counterstroke. By this time, Toulson established a great rapport with the battalion like a family doctor with his practise. One April afternoon at Gommecourt Park, “a spiky knoll of hacked and haggard trees, of vast chalky craters, and of a ramifying subterrane,” Chapman was leisurely gathered with the battalion’s officers and staff.[9] Capturing their reposed mood, Chapman remembered a tedious rant from their signal officer over yet another severed phone cable when suddenly…

“The doctor stuck his nose in the air and crooned:

‘There’s a girl in the heart of Maryland

With a heart that belongs to me;’

breaking off to remark: ‘Say boys, when the old Boche got through the other afternoon, I began to wonder whether he’d shoot me for a spy. This funny old hat Gen’ral Pershing fitted us out in don’t some-how look the real thing… What I’d give to be home naow, riding down Charles Street Bully-vard, Baltimore, in an automobile with a pretty girl under my arm.”[10]

The battalion would soon be in the line again in May, repeatedly at the tip of the BEF’s Third Army spear until the Armistice. But it was not long for the good doctor. At the start of July, Toulson bid adieu to the 13th RF in order to join his American comrades and fellow physicians serving Evacuation Hospital 8, AEF. With them, he survived both St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne.[11] The doughboys thus benefited from his experience looking after the Royal Fusiliers in both body and spirit, fulfilling the mandate of the original USMRC and RAMC mission. He had been lucky. Of the 1,649 physicians in the programme, 37 perished, one of whom, Lt. George P. Howe, was killed in action serving the 37th Division’s 10th RF in September 1917. The situation was no less dangerous for the doctors upon leaving the BEF as half of the 37 doctors fell in service of the AEF.[12]Toulson ultimately returned to Baltimore in 1919 to lead a remarkable urology career, devise a new surgical procedure, ascend to the presidency of the Société d’Internaional Urologie, raise three children with his wife Helen, and live to 95.

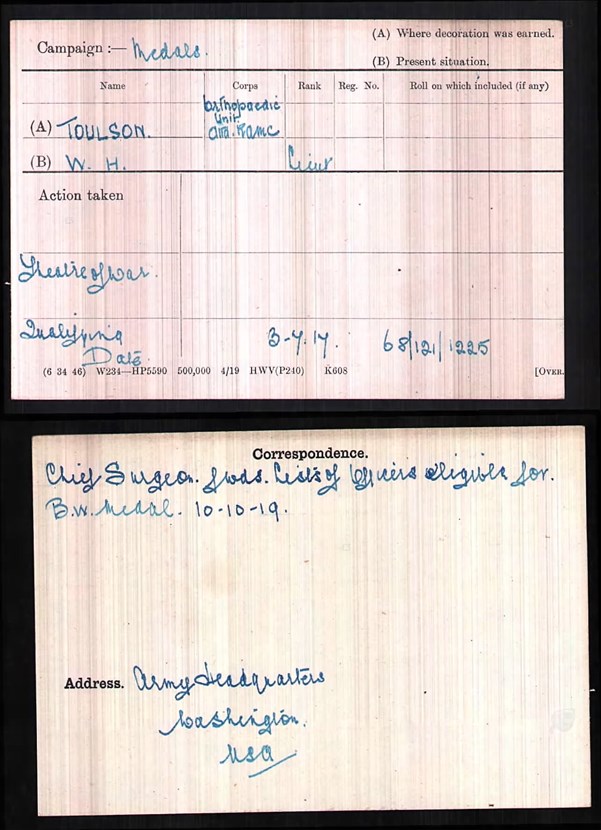

Above: The Medal Index Card for William H Toulson (from the WFA's Medal Index Cards available on Fold3)

Above: The Medal Index Card for William H Toulson (from the WFA's Medal Index Cards available on Fold3)

[1]Michael Rauer, Yanks in the King’s Forces: American Physicians Serving with the British Expeditionary Force during World War I, ed. Sander Marble (Washington, D.C.: Office of Medical History US Army, 2007), 2,4.

[2]Rauer, 7–8, 17–18.

[3]“War Diary of 49th Field Ambulance,” n.d., WO/95/2525/2, TNA. Each division possessed three RAMC Field Ambulances companies.

[4]“Toulson Signet Letter,” Bulletin of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and College of Physicians Surgeons II, no. 6 (April 1918): 233.

[5]“War Diary of 13th Royal Fusiliers,” n.d., WO/95/2532/4, TNA.

[6] Effectively a history of both Blunden’s war experience and that of the 11th Royal Sussex, 39th Division.

[7]Guy Chapman, A Passionate Prodigality: Fragments of Autobiography (Ivor Nicholson & Watson Ltd., 1933), 257.

[8]Chapman, 258.

[9]Chapman, 303.

[10]Chapman, 303.

[11]Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917-1919, vol. II (Baltimore: Twentieth Century Press, 1933), 2105.

[12]Michael Rauer, Yanks in the King’s Forces: American Physicians Serving with the British Expeditionary Force during World War I, ed. Sander Marble (Washington, D.C.: Office of Medical History US Army, 2007), 3, 32–33.

Article by Alexander A. Falbo-Wild