Eton Street 'Shrine' in Hull and the loss of the Earl

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Eton Street 'Shrine' in Hull and the loss of the Earl

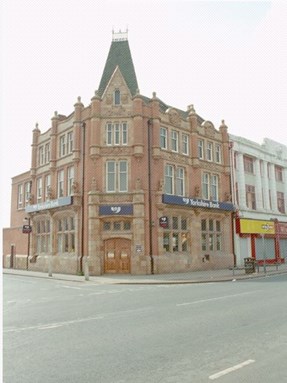

At the corner of Eton Street and Hessle Road in Hull stood until recently a branch of the Yorkshire Bank. As with most cities, the closure of bank branches has accelerated in recent years leading to further declines in local services. This is nothing new - this area of Hull has been subject to changes and ‘slum clearances’.

It was during these clearances that many ‘street shrines’ were destroyed. These shrines listed men from the neighbourhood who were killed in the First World War. It seems that the creation of these street shrines is something that became a specialty in the city of Hull.

The variety and diversity of permanent war memorials may well have been inspired by Hull’s earlier Street Shrines.

The first and earliest war memorials in Hull were the Street ‘Rolls of Honour’, started in 1915. They commemorated all those locally serving in the armed forces. The idea of street war memorials started in South Hackney, in the East end of London, but it was soon adopted in other towns. These "wayside altars" became particularly widespread in Hull between August and December 1916, and by the end of 1916, Hull had at least 120 Street Memorials. They continued into 1917, when the Raglan Street and George Street Memorials were unveiled. They were supported by local churches and chapels, who observed a “spiritual awakening” in the community.

Very few of these street shrines survive. But the shrine opposite the now empty Yorkshire Bank branch is one that miraculously remains intact.

The Hull Daily Mail reported on many unveilings and printed a number of “Rolls of Honour”. However, there were often mis spellings, wrong initials, incorrect regiments and other errors. Sometimes, the same servicemen appeared on several memorials. This was because soldiers moved address or were included on memorials by relatives in other streets who themselves moved.

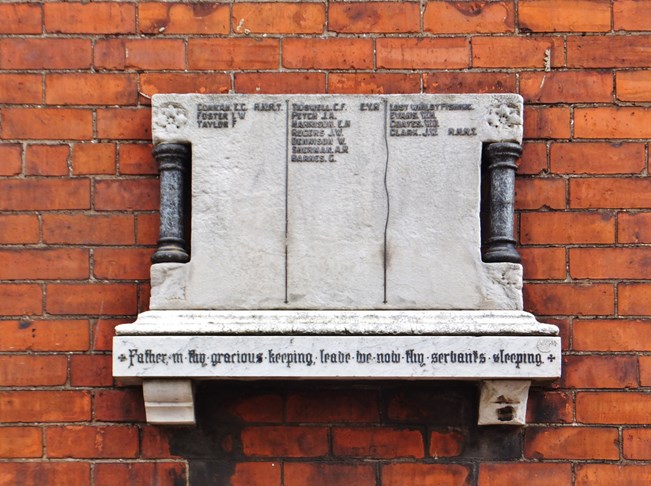

A resident from Osbourne Street, complained to the newspaper that their Street Memorial should be reprinted, stating there were “dozens of mistakes” and some men had been omitted from the list, even though their names had been submitted. Similarly, the current Eton Street marble memorial bears little resemblance to its original “Roll of Honour”, which included many more names of men killed in the war

Eton Street converted their Roll of Honour to a marble memorial in 1921, but ran out money and included only a few of the men lost.

Records suggest that the Eton Street memorial represented 260 houses with 204 men serving.

Many Street memorials were destroyed during the Second World War blitz, which devastated 90% of Hull. Others were lost through post war reconstruction and slum clearance in the 1970’s. Just a few examples of Hull Street memorials survive today. Most notably, these are at Sharp Street, Newland Avenue, Eton Street, on Hessle Road and on Hull’s Dansom Lane. Other examples of street shrines are also preserved in the Hull Transport museum.

As well as missing the names detailed on the original memorial, the Eton Street shrine has been damaged – the two columns which originally held a decorative capital which is no longer there - it has been missing for many years.

The men named are divided into three 'columns' We have men of the Royal Navy on the left.

Leonard Foster, and

F Taylor

In the centre are men who were killed in the British Army - all were in the East Yorkshire Regiment

Charles F Tidswell of Nile Street

James Petch of Eton Street

But the right hand column is headed ‘lost whilst fishing’

This includes

WD Coates

It is the name WD Coates that this article will concentrate on. This could refer to one of two men – father and son who were the skipper and 3rd Hand respectively of the Steam Trawler ‘Earl’. Both had the Christian names ‘William Darby’. The father was born in 1860 and the son in 1895.

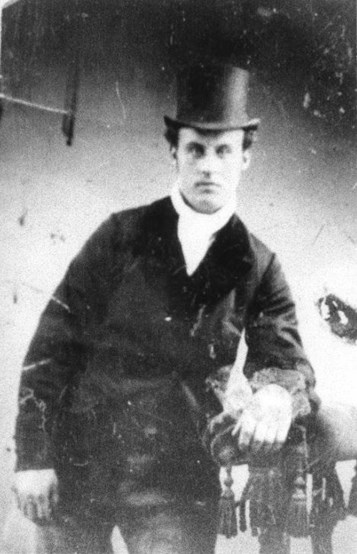

Above William Darby Coates (snr)

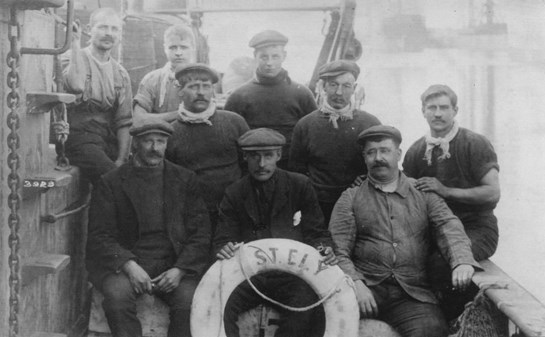

Skipper, William Darby Coates (Senior) of the steam trawler “EARL” - on this occasion photographed with his crew on the trawler 'Ely' (https://ww1hull.com/directory-newtest/listing/coates-senior-william-darby/)

Above 'Ely'.

Fishing was a hard business as recounted by William Oliver

There were two distinct types of craft – the sailing smack and the steam trawler. The steam trawlers were of two classes: the boxmen and the single boaters. The few smacks operating were all in the box fleets, and there were two such fleets operating from Hull at that time – the Great Northern Steam Fishing Co, and The Hull Steam Fishing and Ice Co, known as the Red Cross, because a red cross was the distinctive mark on the trawlers’ funnels.

The fleets were under the control of an ‘Admiral’ who was appointed by the company for his exceptional knowledge of the fishing grounds, and was always in a sailing smack. They fished in the North Sea, chiefly on the Dogger Bank, and it was the Admiral who selected the particular ground to fish. His vessel carried distinctive marks – a flag on his fore-stay about halfway up and a flag at the masthead. When he hauled his masthead flag down, it was the signal to shoot the trawl.

On a January morning in 1898, I went to the St Andrew’s Dock to look for a ship. I was 13 and a half years old. I wanted to go in a smack so that I would be away a long time, as if I made a short trip I had good reason to think that my father, who, at that time, was a very successful skipper fishing the North Sea, would stay ashore to prevent me going to sea.

Before noon, I had signed on with a smack, the Emperor, belonging to Robins. When I gave my age correctly, I was told I would not be allowed to sail until I was 16. In my eagerness, I admitted to making a mistake in my age, and signed on as 16. So, on 14 January, I sailed through the lockpits of St Andrew’s Dock as a cook, with William Haycock as skipper.

Of the next two or three days, I prefer to say very little. I did no cooking, but spent most of my time stretched out in the small engine-room in the agonies of sea-sickness. After two days of this, I begged the skipper to send me home as soon as we joined the fleet, but he made it quite clear that he would not send me in until it was possible to obtain a relief for me. But, by the time we joined the Great Northern fleet, I was much better and I tried my inexperienced hand at cooking. The results must have been grim, but my terrible meals cannot have had many ill effects on the digestive organs of the crew...[1]

Returning to William Coates, father and son: William (aged 50) was skipper of the Steam Trawler 'Earl'. This vessel was lost in mysterious circumstances on 21 January 1916.

Many fishing vessels were lost to enemy action. One count suggests this numbers over 400 between 1914 and 1916 with a further 300 in 1917 and 1918.[2] This does not however include vessels - such as the Earl - which were lost in 'unknown' circumstances.

The Earl

Fishing trawler 'Earl'

The Earl was owned by the Great Northern Steam Fishing Company – which William Oliver mentioned above.

Whilst many Hull trawlers were used in the war for minesweeping, it is likely that the Earl was simply engaged in a fishing trip - departing from Hull for what should have been a routine trip on 21 January 1916. She set sail with a nine-man crew. These were (alphabetically)

A Brownhill (ship's cook) aged 51 of 140 Regent Street

William Buchan (trimmer) aged 17 of 30 Haddon Street

William Coates (skipper) aged 59 of 25 Buxton Terrace, Daltry Street

William Coates (3rd hand) aged 20 of 6 Empringham Place, Daltry Street

Frederick Jackson (2nd hand) aged 34 of 236 Boulevard

W Mason (4th hand) aged 50

J Willie Mellor (First Engineer) aged 40 of 6 Glasgow Street

George Newmarch (Botswain) aged 36 of 3 Helen Terrace, Marmaduke Street

B Patterson (2nd Engineer) aged 22 of 1 Blenheim Crescent, Rugby Street.

All these addresses are within half a mile or so of the memorial at Eton Street. Truly a close-knit community.

The Earl itself was not an old vessel. Built in 1898 at 169 Gross Registered Tons, she was 104' long, and 20' wide. With an engine and one screw she also (as seen above carried sails to assist the steam powered 40 HP engine.

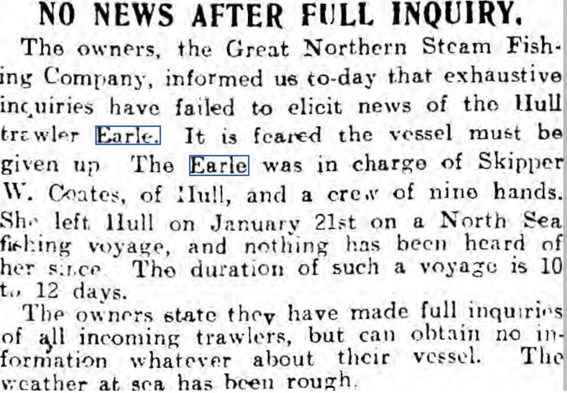

The Hull Daily Mail carried this small paragraph on 19 February 1916

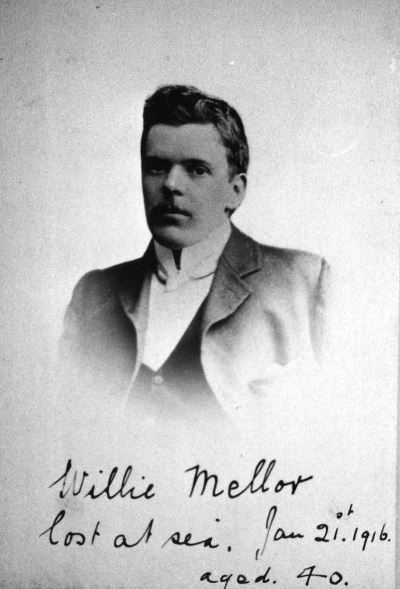

Besides the photo of William Coates, we also have an image of first engineer Willie Mellor

Willie was born in Ravensthorpe in 1875, and had presumably settled in Hull, where he lived at 6 Glasgow Street with his wife. In July 1915, Willie signed up with the Great Northern Company. After completing the first trip, lasting less than two weeks, Willie signed on again for another ten trips, the first of these, later in July 1915, being under a new skipper, W.D. Coates. Although the skipper and the ‘second hand’ earned a proportion of the catch, Willie, as First Engineer was the highest salaried individual on board, earning the very respectable sum of 47 shillings, 6d per week.

Nothing was ever heard of the Earl. The crew are named on the Tower Hill Memorial.

The Memorial commemorates 12,649 men of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who died in the First World War and who have no known graves.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

[1] https://fishingnews.co.uk/news/hull-trawler-memories/

[2] https://www.naval-history.net/WW1LossesBrFV1914-16.htm

Other resources

Presentation "A forgotten Navy: Fishermen’s involvement in the Great War"

A BBC radio interview talks about the Eton Street Shrine and WD Coates here: BBC Sounds